This article seeks to establish, on the provisional basis of the materials in the Archives examined to date, the course of events surrounding the Baptismal Font, i.e., A555,1, A555,2 , A555,3, A555,4, from commission to installation. Following this, an attempt is made to determine, as far as is possible, the history of the two additional marble versions of the baptismal font, which are presently installed in the Reykjavik Cathedral and the Church of the Holy Spirit in Copenhagen.

The original commission of a baptismal font for Brahetrolleborg Kirke was made by Countess Charlotte Schimmelmann, in a letter dated 2.11.1804 from Baron Herman Schubart to Thorvaldsen. The first preparatory clay work was undertaken at Montenero during the summer of 1804, and the font was reported ready for shipment on 22.10.1808. It was only during the autumn of 1815, however, that the font arrived in Copenhagen, where it was exhibited and admired at Charlottenborg Palace. On 2.11.1817I, it was dedicated in Brahetrolleborg Church. In commemoration of his Icelandic heritage, Thorvaldsen planned a slightly altered version of the baptismal font as a donation to Myklabye Church in Iceland, and apparently began work on this in 1822. However, Thorvaldsen either became dissatisfied with the result, or was tempted by an offer by a prospective purchaser—reportedly Du Pré Alexander, second Earl of Caledon—and sold this font during or around 1827. Immediately thereafter, Thorvaldsen began production of a new version of the baptismal font, intended to fulfill his wish to honor Iceland. While it cannot be determined with certainty when this font was completed, it is known that it did reach Copenhagen in 1833, and arrived in Iceland only in February 1839. There it was installed not in Myklabye, as originally intended, but in the Reykjavik Cathedral. Following the death of the Earl of Caledon, meanwhile, his version was acquired by the wholesaler Anton Boyer (1878-1957), and was donated to the Church of the Holy Spirit in Copenhagen. It is hoped that, once examination of the relevant material in the Archives is complete, it will be possible to reduce or eliminate the remaining uncertainty surrounding the latter two marble versions.

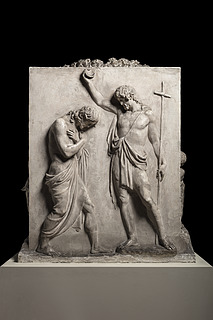

The Baptismal Font in Brahetrolleborg Church is in the shape of a rectangular parallelepiped (cuboid), adorned with reliefs on its four vertical sides, and furnished on top with a cavity for the baptismal bowl. The following motifs appear on the sides of the font:

The Baptism of Christ, A555,1  Christ Blessing the Children, A555,4 |

Mary with Jesus and John as children, A555,2  Three Hovering Angels, A555,3, which possibly symbolize faith, hope, and love |

Thorvaldsens Museum is in possession of the original model in plaster, Baptismal Font, A555,1, A555,2 , A555,3, A555,4, which differs from the marble version by the addition of a floral garland on top, in place of the cavity found on the Brahetrolleborg Font. This garland was presumably a separate cast subsequentlyII affixed to the font.

In addition, numerous variations on and reproductions of the individual reliefs were produced as standalone reliefs.

The baptismal font was commissioned by Countess Charlotte Schimmelmann, sister of Baron Herman Schubart, for their other sister, Countess Sybille Reventlow; on this see the letter dated 2.11.1804 from Schubart to Thorvaldsen. In this letter, Schubart first describes Charlotte Schimmelmann’s wish, and then offers his own suggestion for a motif:

“Je voudrois de la main de Thorwaldsen une Coupe ou un Vase pour le bapteme pour l’eglise à Trolleborg de notre Soeur Reventlow. [...] Je voudrois l’avoir sur un simple piéd de Stal un vase rond tel qu’on s’en sert pour le bapteme, entouré d’un coté d’un bas relief; car de l’autre il seroit contre le mur du temple. Je voudrois que ce bas relief fut analogue au sujet; mais priés Thorwaldsen de me dire a peu près ce que cela pourroit couter, et il n’y auroit rien qui presse. Le vase même devroit etre de marbre blanc de Carare. Quant au pied de Stal il pourroit etre de granit où autrement comme Thorwaldsen le trouveroit bon; mais que ce pied de Stal ne fut pas cher. Reponse la dessus mon bon frere!—

“This work could be quite beautiful, and if the Muses simply cannot be set upon it, then little genii, Religion, Caritas, or something similar could be fitting. You could send me a sketch approximating what you think best.”

Originally, then, the commission was conceived as a baptismal bowl or vase adorned with reliefs and set on a single pedestal. The final marble version, as installed in Brahetrolleborg Church, thus differs substantially from the original wish behind the commission, in part by not including a specific baptismal vase, and in part by being decorated on all sides and placed freely in the church in front of the altar.

Thorvaldsen seems to have responded to Schubart’s letter no earlier than December 7, 1804; but his response has not been preserved, nor has the accompanying sketch. Nevertheless, two extant drafts of Thorvaldsen’s response (30.11.1804 and 7.12.1804) do give a sense of the letter’s content. In the draft dated 7.12.1804, Thorvaldsen accepts the commission: “… I need your advice before I can make a complete dra[w]ing; in the meantime, I hereby send this little sketch[.]”

A sense of the motif of this lost draft can also be gleaned from the other extant draft, dated 30.11.1804, which includes two minor sketches of the baptismal vase.

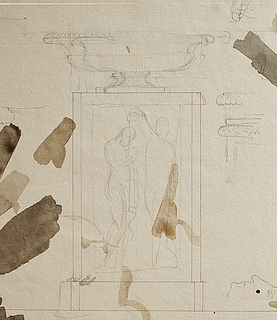

Sketches of the Baptismal Font on the draft letter dated November 30, 1804

Both show a relatively tall, cubic pedestal crowned by a single, unadorned baptismal vase. On the pedestal on the left, which is somewhat wider than the right-hand one, we see a motif that closely resembles the motif of Christ’s baptism as it appears on one of the reliefs of the finished baptismal font, namely, A555,1. Already at this early stage, therefore, Thorvaldsen had a preference for decorating the pedestal rather than the baptismal vase; what is more, he had already chosen the font’s main motif. However, in the upper right-hand corner of Thorvaldsen’s sketch of Agamemnon’s Fight with Achilles, C23, we find a small sketch of a baptismal font with a motif that more closely resembles a representation of Caritas, or of Mary with Jesus and John as children, than of the baptism of Christ. A variant of this motif, too, was used in the final version.

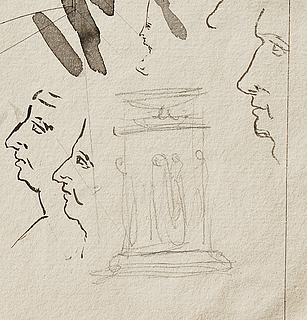

Sketch of the Baptismal Font, in an extract from C23

Another sketch of the font is found on Thorvaldsen’s sketch of a sculpture of Diomedes with the Palladium and Odysseus, C8r, which Thorvaldsen mentions in his draft letter dated 7.12.1804, written in response to the font’s commission. Here we see another of Thorvaldsen’s typically succinct sketches: in only a few wavy lines, he has drafted the Baptismal Font with a Caritas motif on the facing side.

Sketch of the Baptismal Font, in an extract from C8r

However, the sketch that Thorvaldsen sent to Schubart must have been quite similar in motif to the left-hand sketch on the draft letter dated November 30, 1804. This is clear from Schubart’s response, dated 28.12.1804: “I have sent you[r] sketch to Copenhagen, and I have no doubt that the baptizing John will meet with the utmost approval. ... I am also well-disposed to setting the bas-relief on the pedestal, rather than on the vase …”

This early dating of the sketch, including the motif of Christ’s baptism, refutes the otherwise unsupported thesisIII by (Carl Rudolph) Theodor Oppermann to the effect that Jacqueline Schubart was the source of the ideas behind the baptismal font’s Christian motifs.

In a letter dated 4.3.1805, Schubart passed on to Thorvaldsen his sister’s positive reaction to the sketch: “Ce petit dessin de Thorwaldsen est vrayment charmant. Une colonne de la hauteur d’une table avec ce bas relief iroit parfaitment bien, et seroit precisement notre fait. L’idée est delicieux … Le vase seroit simple et de cette forme qui est très jolie.”

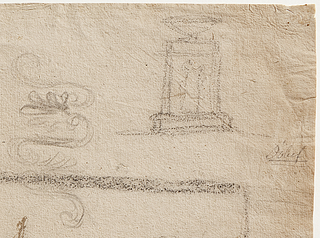

Other sketches of the baptismal font, C66r, derive presumably from the period January-November 1805IV, and may have been produced partly in collaborationV with Thorvaldsen’s good friend, the architect C. F. F. Stanley.

Thorvaldsen, presumably in collaboration with C. F. F. Stanley: Sketch of the Baptismal Font, excerpt from C66r

Thorvaldsen: Sketch of the Baptismal Font (and profile portraits), excerpt from C66r

The uppermost sketch displays an elevation of the baptismal font, presumably by Stanley, with the motif of Christ’s baptism set on the pedestal’s facing side by Thorvaldsen’s hand, and at top (presumably again by Stanley) a large bowl (kylix krater), whose upper edge is decorated with a garland of leaves.

The lowermost sketch on the other side of the paper reveals, when rotated 90° to the right, a much smaller sketch by Thorvaldsen with a corresponding motif, but indicating the presence of reliefs not only on the facing side, but also on the other sides of the font. Diagonally to the left of this sketch, a line from a triangular pedestal to the font can be seen, presumably by Stanley. Meanwhile, beside the elevation of the baptismal font with the baptismal bowl, the pedestal’s upper left-hand corner is drawn in an inset, with the addition of a leaf pattern and another indistinct indication of work on the inset. On the left side of the elevation, we find a inset drawing of the base of the baptismal bowl. Apart from those showing the corner and the base of the baptismal bowl, these insets were produced with India ink following a ruler, whereas Thorvaldsen’s drawings were executed freehand.

No later than August 1805—and probably by the time he received Countess Schimmelmann’s approval of the sketch he had sent; cf. Schubart’s letter dated 4.3.1805—Thorvaldsen must have decided definitively to decorate the sides of the pedestal instead of the baptismal vase. It is impossible to determine, meanwhile, when the baptismal vase was replaced entirely by the cavity. As late as the summer of 1805, Sybille Reventlow was still describing the commission as including a baptismal vase: in Schubart’s letter dated 26.7.1805, she passed on the measurements of the church’s existing baptismal bowl. It thus appears that the removal of the vase from the commission took place quite late in the course of its history.

It is probable that Thorvaldsen began preparatory work on the reliefs for the baptismal font’s four sides in August 1805, during his stay with the Schubart family at Montenero, and that he started with the relief portraying the baptism of ChristVI, possibly A736. This can be discerned from Schubart’s aforementioned letter dated 26.7.1805, in which Schubart suggested that Thorvaldsen start work on the baptismal font there; from Thorvaldsen’s letter to Anna Maria Uhden dated [26].8.1805, in which he writes that he has just begun the work; and particularly from Schubart’s subsequent letter to Thorvaldsen dated 16.9.1805, where he writes that he will travel to Leghorn the next day, in order to ship the relief of The Baptism of Christ to Thorvaldsen in Rome.

The composition is quite similar to the left-hand sketch on the draft dated 30.11.1804, and demonstrates that Thorvaldsen held fast to his original plan.

The other three reliefs on the font, A555,2, A555,3, and A555,4, were completed between 1806 and 1808. On 22.10.1808, Thorvaldsen was able to inform Countess Schimmelmann by mail that the baptismal font was ready for shipment at her request.

The only payment requested by Thorvaldsen was for 487 piasters, to cover the costs of purchasing and transporting the fine carrara marble used in the baptismal font, as well as the rough carving by his “wage workers”; on this see the draft letter dated 22.10.1808. According to Thorvaldsen’s draft letter to the Countess dated 4.2.1809, the price was calculated as 483 scudi, and under normal circumstances, Thorvaldsen would have appraised his own artistic contribution to the work as equivalent in worth to the same amount: “… and that I humbly value my art and toil as equivalent to the aforementioned chargeVII.” It was this last portion of the payment that Thorvaldsen decided to forego, in exchange for the honor and prospect of becoming better known and valued in his homeland.

Originally, this highly favorable price may in part have been a product of Thorvaldsen’s hope that Charlotte Schimmelmann, out of gratitude for his magnanimous gesture, would “show consideration for” Thorvaldsen’s old, destitute father; on this see the letter dated ca. 23.9.1806 from Thorvaldsen to Nicolai Abildgaard. As is well known, however, the elder Thorvaldsen died on 24.10 of the same year; so regard for his father cannot have been what motivated Thorvaldsen to lower his price in 1808.

If Schubart is to be believed, Thorvaldsen’s generous gift was no miscalculation. In a letter to Thorvaldsen dated 26.7.1805, Schubart wrote the following: “She [Charlotte Schimmelmann] cares so much for you that I cannot deny that I am fairly sure that she contributed a little to your appointment as Professor [at the Royal Academy of Arts in Copenhagen that same year].” It thus seems natural that with this in mind—as well as the thought of a smooth road to official commissions for the Danish nation—Thorvaldsen found it both reasonable and opportune to sell the baptismal font at a nominal price.

Schimmelmann’s gratitude and good will did indeed endure. In a letter dated 17.11.1808, she thanked Thorvaldsen for the completed work and for his generosity, and briefly complained of the impossibility of shipping it to Denmark, due to the ongoing state of hostilities in Europe. As a token of thanks for Thorvaldsen’s generosity, the countess enclosed an “agrapheVIII of diamonds”; cf. the letters from Schubart to Thorvaldsen dated 26.12.1808 and 13.1.1809. In the first of these, Schubart went on to cite a passage about Thorvaldsen in his sister’s letter:

“My husbandIX and I acknowledge, as we should, his noble treatment of us. Count Christian ReventlowX promised me that he will be used, and used even more for our reborn palaceXI. He will be given large statues to complete, bas-reliefs and more; and you, my dear brother, can trust in Reventlow’s eager regard for your friend Thorvaldsen, whom HansenXII has also taken such an interest in. This artist is truly proving his merit to the fatherland—etc[.]”

Thorvaldsen’s partial gifts to the Reventlows thereby proved to have borne fruit.

The baptismal font’s delivery to Denmark was delayed extensively. As of January 1815, it had still not been delivered; this is clear from a letter dated 9.1.1815 from Schubart to Thorvaldsen. Here Schubart pressed Thorvaldsen to send the font to Leghorn as quickly as possible, “as there is a skipper from Flensburg there named Hansen, who is ready to sail, and who will be departing for Elsinore in February; and so we will soon have the joy of having this masterpiece of art in our possession here. What particularly moves me to implore you, my best friend, to make haste with this errand, is the following …” The reason for this sudden haste was that Schubart’s niece, Countess Josephine SchimmelmannXIII, was pregnant, and they hoped to inaugurate Thorvaldsen’s baptismal font with this baby’s baptism. Schubart himself was to be the godfather, and described plans to build a separate chapel for the font:

“… This will be purely and simply in Roman style. Ask my good friend Malling to make me a sketch of such a chapel, [as we have] excellent architects, as well as decorators who could put friezes all around the interior of the chapel, and adorn it with a layer of fluted columns in Corinthian style … The baptismal font will be elevated by a staircase that will be marbleized, and this will be done in a beautiful way so that, when in use, one will ascend it with the child to approach the [place of] baptism.”

This planned chapel for the baptismal font was not, however, completed.

In the fall of 1815, the baptismal font finally arrived in Denmark (see Thiele 1831, p. 73), and was exhibited as catalog no. 17 in a salon in Charlottenborg Palace on the occasion of the coronationXIV of Frederik VI on July 31, 1815. However, the font had an extremely successful advance showing before reaching the Charlottenborg salon, while it was installed in the vestibule of the Schimmelmann Mansion (now Odd Fellows Mansion); cf. Molbech, op. cit., p. 373:

“It … became known throughout Copenhagen in a very short time that it was possible to view Thorvaldsen’s baptismal font with a minimum of inconvenience … and one saw, on a daily basis, people of all classes streaming there to marvel—or, perhaps more accurately, to learn to marvel—at a three-dimensional masterwork by the foremost sculptor of the day. There was but a single opinion of its excellence, and every single one left it enriched with new conceptions and ideas, as well as with undivided admiration for the great artist.”

Put briefly, the work awakened more than the usual enthusiasmXV, and contributed to reviving and hastening plans for bringing Thorvaldsen back to Denmark to produce works for the nation. The baptismal font can be said to have been the first real work that Thorvaldsen could put on display in DenmarkXVI.

The baptismal font in Brahetrolleborg Kirke. Photo: Wermund Bendtsen, March 1980.

Exactly thirteen years after the commission was sent, the baptismal font was finally dedicated in Brahetrolleborg Church on 2.11.1817. Though no new chapel was constructed for the work, the church’s interior was renovated as part of the preparations for the work’s arrival. The font was given a central, free place in the church in front of the altar. In a letter dated 13.12.1817, Ditlev Reventlow expressed thanks for the work, and enclosed a bookletXVII for Thorvaldsen containing speeches and songs from the dedication ceremony. Reventlow’s letter included the following remark on the placement and effect on congregants of the font (which was most commonly called “the baptismal stone” or simply “the stone” in letters of the day):

“The stone [i.e., the baptismal font] was assigned as good a place in the present church as the opportunity allowed, by a total alteration of the church interior, and I hope that when you someday visit Denmark, you will not pass by Trolleborg without visiting it, and that you will be pleased with the spot that your artwork has been assigned. It is freestanding on all sides, and has quite good lighting; and since its dedication, quite a few children have been baptized in it, and home baptism, which had become so common here, will presumably now only take place when necessity demands, as people are so eager to bring their children to the holy place in the church. This has also moved me to become aware of the impression your artwork has made on the common people here; but they would have to be souls of an unusual type not to feel the artwork’s worth when beholding it. ...”

For installation in a church in Iceland, Thorvaldsen prepared a slightly altered marble version of the baptismal font. In this version, among other changes, the pedestal is crowned with a floral garland, and the reliefs Jesus Blesses the Children and Mary with Jesus and John as Children come to an end just below sharply protruding support-plates. What is more, on the relief with the hovering angels, the font bears the following inscriptionXVIII:

OPVS HOC ROMAE FECIT

ET ISLANDIAE

TERRAE SIBI GENTILICIAE

PIETATIS CAVSA DONAVIT

ALBERTUS THORVALDSEN

A. MDCCCXXVII

This gift was originally intended for the church in MyklabyeXIX, Blönduhlið district. Thorvaldsen’s fatherXX was born in this town, and his grandfather, Thorvaldur GottskalkssonXXI, had been priest in the church, had been responsible for its erection, and lay buried at its entrance. It is clear from Thorvaldsen’s workshop accounts that he had a baptismal font in production from September 1826 until March 1827. This matches Thorvaldsen’s letter dated 4.2.1827 to Prince Christian Frederik, which discusses the baptismal fonts’s shipment to Denmark:

“It is with great pleasure that I, your most humble servant, have received your Royal Highness’s honored writing of November 25, whe[re] I see that it has pleased His Majesty to command that a frigate be sent to Leghorn to collect some of my works: Be assu[r]ed that I will seek to make as good use as possible of this occasion. However, I do not dare to promise anything more finished in marble for shipment than … a baptismal fon[t] that I wish to donate to a church in Iceland.”

Several drafts of this letter describe the baptismal font as already complete. What is more, letters to the Building Commission for Christiansborg Palace, dated 4.2.1827, and to the Building Commission for the Church of Our Lady, Copenhagen, dated 12.2.1827, both include the font in a list of works that will be ready for shipment two months hence. It further emerges that Thorvaldsen had made an extraordinary request to have the Icelandic baptismal font included in this shipment, even though it was otherwise “intended for” works to be used in Christiansborg Palace and the Church of Our Lady. It may thus be inferred with certainty that the baptismal font was complete by the late winter or spring of 1827.

A sketch of the baptismal font, displaying the relief The Baptism of Christ, is visible on a letter dated 13.5.1826 from the Royal Shooting Society of Copenhagen to Thorvaldsen. This sketch can be assumed to have been drawn by Thorvaldsen during the same period.

Nevertheless, there is no indication that the font was shipped as planned. In a letter dated 7.5.1827, the Danish architect C. F. Hansen asked whether the baptismal font intended for Iceland could be installed in the Church of Our Lady until Baptismal Angel Kneeling, A112, was finished, so as to allow the dedication of the church to proceed during the summer of 1828. This, however, did not take place. A plaster cast of the font only reached Denmark in 1829, and a marble exemplar only arrived in 1833, as described below. The delivery of this version of the font was thereby delayed in a manner similar to the delays that affected the original font for Brahetrolleborg Church.

In May 1827, the shipment of the baptismal font was postponed until the spring of 1828, so that all of the commissioned works could be completed and shipped at onceXXII. Soon afterwardsXXIII, the Building Commission for the Church of Our Lady in Copenhagen offered to ship the works it had commissioned, together with the baptismal font, already at the end of 1827; but this came to nothing as well.

Even though the baptismal font was complete in marble in 1827, Thorvaldsen at first sent only a plaster cast to Denmark. In a letter dated 5.2.1829, Thorvaldsen wrote as follows to Ove Malling:

“With regard to the angel kneeling before the baptismal fontXXIV and the baptismal font intended for Iceland, I have produced casts of both and sent them to Copenhagen, and I hope they will arrive in time. I have already written to the High CommissionXXV on this matter.”

One day after Thorvaldsen wrote the above lines, Lorentz Angel Krieger, the newly-appointed diocesan prefect for Iceland, composed a request to Thorvaldsen, which was then forwarded to him in a letter dated 6.5.1829. Krieger asked Thorvaldsen to ship the baptismal font that same year, so that it would reach Iceland before the onset of the autumn storms, which would delay its shipment by yet another year. In fact, it was to be ten more years before Iceland would receive the gift.

In 1830, the plaster version was displayed in the Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition as catalog no. 165XXVI, under the title “Baptismal Font intended for Myklabye Church, Iceland.”

After this a long silence fell on the baptismal font’s fate. It was not until 16.5.1833, in a letter of that date from Thorvaldsen to C. F. Hansen, that a marble version of the font intended for Iceland finally appeared on a list of works to be shipped in advance of Thorvaldsen’s then-planned trip to Denmark in February 1834. A letter dated 8.10.1833 from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts to Thorvaldsen indicates that the works arrived safely.

The baptismal font in Reykjavik Cathedral. Photo: Margrethe Floryan, 2017.

It was only in February 1839 that the marble baptismal font reached Iceland. There it was installed in Reykjavik Cathedral, rather than in Myklabye, as originally planned; see the letter to Thorvaldsen dated 5.9.1839, from the Diocesan House of Iceland. The reason for this change in location is unknown; but perhaps Thorvaldsen had become convinced, in the intervening years, that his work deserved a more prominent placement than in the simple church of his father’s home parish. Nor can it be determined with precision when this change took place. In the aforementioned letter by Krieger dated 6.5.1829, the font is already described as intended for the cathedral in Reykjavik, while earlier the same year it is mentioned as intended for Myklabye Church in a letter from F. F. Friis’ 8.1.1829 to J.M. Thiele. The same discrepancy is found between the 1830 exhibition and the memoirsXXVII of Baroness Stampe. In short, there was a certain uncertainty for years about the place of the baptismal font designed for Iceland.

In addition, there is further uncertainty regarding which baptismal font in fact ended up in Reykjavik. Thiele writesXXVIII of a report to the effect that the font produced in 1827 never reached Iceland, but was sold to a Norwegian merchant, who had the inscription rubbed off. Meanwhile, Thorvaldsen allegedly arranged to produce a new baptismal font for Iceland in carrara marble. Already in 1854, however, Thiele wroteXXIX as follows about the year 1822:

“During these summer months [Thorvaldsen] made a copy, with some changes, of the baptismal font that he had produced for Trolleborg Church, on commission for Baron v. Schubart. In the artist’s handwritten notes, there are indeed indications of commissions for copies of this baptismal font, both by Prince Esterhazy and by the Earl of Caledon. Perhaps it was such an incomplete exemplar, standing unused, that was now requisitioned for another purpose. It is clear in any case that a new baptismal font was produced in marble, and that this exemplar, as would later be recorded in a Latin inscription, was intended for donation to his ancestors’ island. For Iceland, source of the name that was now pronounced with so much reverence throughout the world, was also to have one of his works. This marble baptismal font was donated in 1827 to Myklabye Church, where his grandfather lay buried by the entrance.”

As is documented above, however, the font neither ended up in Myklabye nor was installed in 1827, so Thiele’s summary is not credible on these points. Moreover, the “indications … in the artist’s own handwritten notes” have not—or have not yet; cf. this article’s introduction—materialized in the Archive; perhaps Thiele obtained his information from another source. There remains Thiele’s mention of 1822 as the year in which Thorvaldsen began work on at least one new version of the baptismal font. Perhaps this refers to the early version that was intended for Iceland, but which (no earlier than 1827, to judge by the inscription) was purchased by another buyer. While Thiele states that the buyer was a Norwegian merchant, the real purchaser appears to have been the Earl of Caledon—whom Thiele also names, but only as the issuer of a previous commission. In the given case, the inscription simply was not rubbed away, as Thiele states. This would explain why the earl’s font bears a Latin inscription intended for Iceland. The latter baptismal font, which was in production from 1826 to 1827, was thus to have been a renewal of his delayed gift to Iceland. According to Thiele, work on the new version was to have begun immediately after the previous version’s sale.

We are therefore dealing with two subsequent marble versions of the Brahetrolleborg Church baptismal font, both of which were originally intended for Iceland. One of these was possibly completed, or at least begun, as early as the summer of 1822, but was bought by the Earl of Caledon in approximately 1827 (perhaps through an unidentified Norwegian middleman); the other would then definitely have been produced between 1826 and 1827. Alternatively, the first version could be the one that was completed in 1827, while the second could have been produced between 1827 and 1833, when the last marble version is known to have been shipped to Denmark. No matter how we assign production dates to the two versions, the fact that the first marble version was purchased in approximately 1827 provides sufficient explanation of the fact that two marble versions are extant today with inscriptions intended for Iceland.

The baptismal font produced later—which is also by far the most beautiful, as well as formed out of a single massive marble block—remains installed in the Reykjavik Cathedral. The other baptismal font has multiple flaws in the marble, and is a fusion of various marble plates instead of a single massive block; it is the one installed in the Church of the Holy Spirit in CopenhagenXXX.

The baptismal font in Church of the Holy Spirit, Copenhagen. Photo: Margrethe Floryan 2017.

The font at the Church of the Holy Spirit was donated to the church by the wholesaler Anton Boyer (1878-1957), who had acquired it at the auction of the Earl of Caledon’s art collections at Christie’s in London on June 6, 1939. Without a doubt, then, this baptismal font is identical with the one mentioned by Thiele in his account of the year 1822XXXI.

Finally, with regard to the “Norwegian merchant” who, according to Thiele, allegedly acquired the first exemplar, art historian Hanne Abildgaard has suggested that the Knudtzon brothersXXXII served as possible middlemen for the earl; but she acknowledges that nothing in their correspondence supports this claimXXXIII.

In his memoirs as told to Baroness Stampe, Thorvaldsen mentions only two baptismal fonts: the original one for Brahetrolleborg, and the one for Iceland. There is no mention at all of the third marble version (i.e., presumably the one that is found today in the Church of the Holy Spirit); this may be because that this version was of lower quality than the other two.

The course of events surrounding the original commission for Brahetrolleborg Church is now well-established. By contrast, numerous uncertainties remain about the two later fonts. Despite Thiele’s statements about commissions from two princes mediated by a Norwegian merchant, none of this can be verified by means of the sources available in the Archives. All that can be established is that one baptismal font, presumably the last to be produced (and probably dating from 1826-1827), ended up in Reykjavik, while the other (possibly begun as early as 1822, initially intended for Iceland, but completed no earlier than 1827, the earliest possible dating of the inscription) found its way to the Earl of Caledon. It is even conceivable, finally, that the Reykjavik font was produced still later than 1827, inasmuch as it was first sent to Denmark in 1833. It is hoped that a more precise dating of these events will be possible once review of all of the relevant documents in the Archive is complete.

Last updated 15.11.2024

Tale og Sange ved Indvielsen af den Thorvaldsenske Døbefont i Brahetrolleborg Kirke, paa Reformationsfestens 3die Dag, den 2den Novbr. 1817 [Speeches and Songs at the Dedication of the Baptismal Font by Thorvaldsen, on the Third Day of the 300th Anniversary Celebration of the Reformation, November 2, 1817]. See the book here.

According to sculptor Rasmus Andersen (1861-1930), former conservator at Thorvaldsens Museum; cf. the Arkkatalog of the Thorvaldsens Museum Archives, inv. no. A555. One may assume that this change was due to the later marble versions of the baptismal font, in which the depression for the baptismal bowl was replaced with a floral wreath.

Cf. Oppermann, op. cit., p. 58.

This dating is based on Stanley’s arrival in Rome at the beginning of January 1805 and his death there presumably on November 18, 1805. For more on this, see Stanley’s biography.

Cf. Thiele’s list of Thorvaldsen’s drawings, no. 66, and Dyveke Helsted’s catalogue of drawings, C66, in The Thorvaldsens Museum Archives.

The reliefs on the sides of the font are found in numerous later versions. The relief The Baptism of Christ is known with certainty to have been produced in a minimum of three versions: the relief on the baptismal font itself; the separate relief The Baptism of Christ, A736; and Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek cat. no. MIN 447. At the auction of some of Thorvaldsen’s effects held at Thorvaldsens Museum on October 5, 1849, no fewer than three plaster reliefs with the Baptism of Christ were offered for sale as cat. nos. 63-65, in the category of Works by Thorvaldsen in Plaster. Of these, no. 63 was evidently not sold, or sold prior to the auction date (in Thorvaldsens Museum’s copy of the auction list, the phrase “did not appear” is noted beside the item’s number); no. 64 was bought by the Spanish diplomat Don Leopoldo Augusto de Cueto (1815-1901), who had been posted to Copenhagen in 1847; no. 65 is recorded as having been bought by C. F. Wilckens, but afterwards the word Museet (‘the Museum’) was added in red, and on a sticker added to the back of the auction list, Ludvig Müller (1809-1891), then a museum inspector, recorded that Wilckens had bought no. 65 (among other items) for the museum: “That … No. 65 was bought for the Museum by Mr. Wilckens at the 2nd installment of Thorvaldsens Museum’s auction, is hereby attested to on November 20, 1849 by L. Müller.”

Without a doubt, No. 65 can only be identical to the relief The Baptism of Christ, A736. This relief differs from that on the baptismal font in part by the fact that the drapery covers somewhat more of the men’s bodies. With regard to the remaining two reliefs, it is unknown whether they were identical copies or variations; nor can it be determined whether they were original models or subsequent casts. As mentioned previously, the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek is in possession of another Baptism of Christ, here called Baptism of Jesus (cat. no. MIN 447), with clearly marked points for marble carving. Here, too, there are smaller divergences in motif from the Baptism of Christ on the Baptismal Font, A555,1, and from The Baptism of Christ, A736. The Glyptotek’s version is listed as having the following provenance: “Auction of Effects of Thorvaldsen, 1859. Bought [for the Glyptotek] by Thorvaldsen’s Valet W. Wilchens. Rasmus Secher Malthe. Carl Jacobsen 1880.” Cf. Jens Peter Munk, Katalog Dansk skulptur 1694-1889 [Catalogue of Danish Sculpture, 1694-1889], Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek (Copenhagen 1995), p. 198.

Rasmus (Secher) Malthe (1829-1893) was a sculptor and helped Carl Jacobsen with art purchases; “W. Wilchens” must be an error for C. F. Wilckens; and the auction of Thorvaldsen’s effects in which the reliefs were sold was, as mentioned, held at Thorvaldsens Museum on 5.10.1849. A second auction was held on November 17, 1858, but here only a frame for the relief was on sale. It is thus most probable that either no. 63 or no. 64 ended up at the Glyptotek as The Baptism of Jesus, and no. 65 is indubitably the Museum’s exemplar of the relief The Baptism of Christ, A736.

It is ultimately clear that one of these three—The Baptism of Christ, A736, or the Glyptotek’s exemplar (The Baptism of Jesus, cat. no. MIN 447), or the third relief (no longer extant)—must be the one that Thorvaldsen produced in Montenero in late August 1805, and which appears on the baptismal font in a later, reworked version. The Baptism of Christ, A736, has no sign of pointing for marble carving; but this does not rule out the possibility that it was the relief produced in Montenero as a forerunner to the one on the Baptismal Font, A555,1.

This reading implies that, in 1809, Thorvaldsen had based the prices he charged for his works on the total actual expenses he incurred for materials and employee wages. The final price was twice this amount, inasmuch as Thorvaldsen held that the same amount was due to him personally as the works’ creator. See also the draft letter dated 22.10.1808, where Thorvaldsen describes his portion of the work as follows: “As far as the work is concerned, my sweetest reward is to have been able to fulfill my benefactress’s command, and I count myself fortunate that you, my most gracious Countess, will possess one of my works, which moreover will serve to make me known in my dear ancestral land [lit. Fædreneland, ‘the fathers’ land’].”

A clip or fastener, used particularly of jewelry; the word is derived from French, where the spelling is now agrafe. Cf. Ordbog over det danske Sprog. This item is not in the Museum’s possession.

I.e. Ernst Schimmelmann.

I.e. Christian Ditlev Reventlow, who was President of the Building Commission for Christiansborg Palace, which commissioned works by Thorvaldsen for installation in Christiansborg Palace.

Namely, Christiansborg Palace. On this see the Related Article entitled Commission for Christiansborg.

I.e. the architect C. F. Hansen.

Countess Josephine Schimmelmann (1790-1852), foster daughter of Charlotte and Ernst Schimmelmann, and married to Count Ditlev Reventlow, son of Ludvig (1751-1801) and Sibylle Reventlow.

Cf. Thiele II, p. 271, and Molbech, op. cit., pp. 253-254.

See also the letters to Thorvaldsen from Peder Malling, dated 20.11.1815, from P. O. Brøndsted, dated 2.12.1815, and from Baron Schubart, dated 5.12.1815.

See, however, Transportation of Thorvaldsen’s Artworks to Copenhagen 1798 and 1802.

Tale og Sange ved Indvielsen af den Thorvaldsenske Døbefont i Brahetrolleborg Kirke, paa Reformationsfestens 3die Dag, den 2den Novbr. 1817 [Speeches and Songs at the Dedication of the Baptismal Font by Thorvaldsen, on the Third Day of the 300th Anniversary Celebration of the Reformation, November 2, 1817]. See the book here.

“In the year 1827, Albert Thorvaldsen produced this work in Rome, and donated it out of respect to Iceland, land of his forefathers.”

Cf. Thiele 1831, p. 73; the letter dated 8.1.1829 from Friis to Thiele, item 30; and the memoirs of Baroness Christine Stampe, op. cit., p. 93.

Namely, Gotskalk Thorvaldsen.

Thorvaldsen’s grandfather, the Icelandic priest Thorvaldur Gottskalksson.

See the letter from the Building Commission for Christiansborg Palace dated 22.5.1827.

Cf. the letter dated 6.6.1827.

I.e., Baptismal Angel Kneeling, A112.

Namely, the Building Commission for the Church of Our Lady, Copenhagen. See Thorvaldsen’s letter dated 5.2.1829.

Cf. Fortegnelse over de ved det Kongelige Academie for de skiönne Kunster udstillede Kunstværker [List of Artworks Exhibited by the Royal Academy of Fine Arts], Copenhagen 1830.

Cf. Stampe, op. cit., p. 93.

Cf. Thiele 1831, p. 164, note 133.

Cf. Thiele III, p. 156.

See under A555 in the Arkkatalog, Thorvaldsens Museum Archives.

Cf. Thiele III, p. 156.

Namely, the merchants Jørgen og Hans Carl Knudtzon.

See A555 (March 1980) in the Arkkatalog, Thorvaldsens Museum Archives.