Norse Mythology in Thorvaldsen's Art - a Virtually Omitted Motive

- Kira Kofoed, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2014

- Translation by David Possen

This article explores the question of why Thorvaldsen did not made virtually no use of Norse motifs. Despite numerous exhortations by prominent Danish personalities to produce works with motifs drawn from Norse mythology, Thorvaldsen did not leave behind even a single finished work of the sort. In general, however, the rediscovery of Norse motifs did form an important part of Danish national self-understanding in the years following 1800.

Norse mythology in Thorvaldsen’s art: a virtually omitted motif

Despite numerous exhortations by prominent Danish personalities to produce works with motifs drawn from Norse mythology, Thorvaldsen did not leave behind even a single finished work of the sort. In general, however, the rediscovery of Norse motifs did form an important part of Danish national self-understanding in the years following 1800. The question of why Thorvaldsen did not made virtually no use of Norse motifs has not yet attracted research; unfortunately, the sources that might help to illuminate the subject are few and indirect.

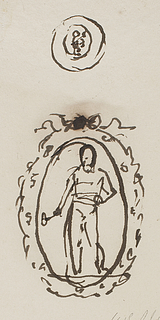

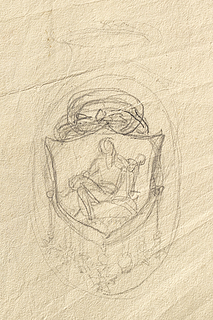

A mere four hand-drawn sketches of Thorvaldsen’s own coat of arms depict a figure who has been identified, presumably correctly, as Thor; cf. C386v, C559a, C559b, and C560r. Yet Thorvaldsen probably never completed these drafts himself. No such finished works are extant, in any case; but understanding the symbiosis in the sketches—a symbiosis between Thorvaldsen as an internationally-based sculptor inspired by antiquity, his Nordic/Norse roots, and the recent rediscovery of Norse mythology—is crucial for gaining insight into the sculptor’s self-understanding with regard to the matter.

Thorvaldsen’s Coat of Arms, possibly 1827, C559a. The dating is based on an inscription on the paper: Rome 4th Febr. 1827. The draft may have been produced later, however, as Thorvaldsen frequently saved and reused his papers. An inscription that arguably reads “THOR” is discernible at the bottom of the escutcheon motif.

The feud over Norse mythology

The Danish National Art Library houses a collection of pamphlets from the period between 1812 and 1821, gathered at the time under the title “Mythologie-Striden” [The Mythology Dispute]. All of these were originally position papers in the scholarly journals of the day. As the collection’s title suggests, debate between the two sides was hardly placid: anonymous slander and personal attacks among the parties were a matter of course. Intriguingly, both sides sought trump cards in alleged statements by Thorvaldsen, which were cited in defense of both of the two main standpoints.

The basic point of contention was the extent to which it is defensible to employ motifs from Norse mythology in contemporary sculpture, given that Christian and classical antique motifs have so long been available to draw on. In Lutheran Denmark, Christian motifs were regarded as paradigmatic. At the Academy of Fine Arts, the use of such motifs was established practice for students competing for the medals that granted access both to higher stages of the Academy’s program and to the final scholarships that would allow them to travel abroad after completing their studies. Meanwhile, classical mythology, particularly that of ancient Greece, was thought to be capable, despite its pagan religious content, of serving art’s purpose: to ennoble humanity by depicting and shaping the beautiful, the great, the true, the good, and the orderly. With the advent of Neoclassicism, and not least with the theories published by archaeologist and art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, both in his 1755 manifesto Gedanken über die Nachahmung der Griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst [Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture] and in his Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums [History of the Art of Antiquity], first published in 1764, ancient Greece came to be taken as an image of the ideal society with democracy, freedom, rational science, advanced philosophy, and the cultivation of the beautiful and the good as cardinal principles. Classical art was regarded as reflecting this ideal society in the purest possible way, and hence was worthy of emulation.

By contrast, the Aesir and Jotun of the pagan North, in their hides, were worshipped by societies and peoples who (in the critics’ view) were far from the Greeks when it came to the visual arts, architecture, or social structure—to the extent that any such accomplishments by the Norse are recognized at all. In Denmark, interest in Norse sagas, legends, and prehistory had been on the ascent since the 1750s, alongside similar bursts of interest in the neighboring countries (in Sweden, for example, these led to the founding of the Geatish Society in 1811). In the wake of the Napoleonic Wars and the state bankruptcy that followed, however, an acute demand suddenly emerged in Denmark for a unifying and edifying heroic image. It was in this context that the “Mythology Dispute” first started to flare up in earnest. As the nation’s educational and advisory body on art, the Royal Academy of the Arts played a central role in this game; indeed, the main parties to the debate were primarily individuals with ties to the Royal Academy.

In Norse mythology art will meet its grave. This is the curt verdict offered by philologist Torkel Baden, secretary of the Academy of Fine Arts, in his monograph Om den nordiske Mythologies Ubrugbarhed for de skjønne Kunster [On the Unusability of Norse Mythology for the Fine Arts]. Baden’s monograph was, among other things, a response to a lecture by the theologian Jens Møller later published as Om den nordiske Mythologies Brugbarhed for de skjønne Tegnende Kunster [On the Usability of Norse Mythology for the Fine Drawing Arts], Copenhagen 1812. Møller went so far as to argue that Norse motifs could be used in membership pieces, but not in medal competitions. While there was a wide consensus that it was appropriate for poets to mine Norse myths freely for material, Baden found it unthinkable that sculptors could derive anything good from them: “Everything that Norse mythology contains is misshapen, useless for fantasy.” Baden was convinced that the motifs found in Norse mythology would detract from art’s highest aims, which only Greek (and Christian) motifs could live up to: “Greek mythology moves them as citizens of the educated world. For in it are contained the principal fundamentals of all the branches of knowledge that dignify humanity and distinguish it from the great horde, namely, the fundamentals of astronomy, geography, chronology, and other sciences that enlighten and sharpen the understanding; and it is the language of fantasy, which all cultivated people understand, and the knowledge of which is first eradicated with the culture.”

As Baden saw the matter, Norse mythology was reconstructed from a slovenly muddle of sources, many of which, moreover, were of murky Greek origin. The resulting corpus is messy and disorderly; only rarely is it clear how an artist might depict these mythic beings so that they could be recognized easily, making the stories at issue accessible to the beholder.

On the side of classical mythology, Karl Philipp Moritz’s Götterlehre oder Mythologische Dichtungen der Alten, Berlin 1791, which is also found in Thorvaldsen’s book collection, M462, illustrates how a cycle of myths was described and activated as a manual, or medieval pattern-book, for artists to consult when seeking to depict a motif correctly according to its sources and precedents. To this can be added the innumerable actual artworks preserved from classical antiquity, which could be studied as casts even in Copenhagen.

The Danish painter C. F. Høyer, a friend of Thorvaldsen, had views similar to Baden’s. From his position as member of the Academy of Fine Arts’ plenary committee, Høyer argued in a series of opinion pieces that in the name of enlightenment and edification, artists should depict Christian or classical motifs rather than those of Norse mythology, which would give rise only to idolatry and barbarism. On 23.6.1821, Høyer sent Thorvaldsen a short pamphlet published earlier the same year as a summary of the painter’s thoughts.

Both Baden and Høyer ultimately fell foul of the Academy, not least because of this dispute. In 1826, Høyer was excluded from the plenary committee; and Baden, citing irreconcilable differences, resigned from his position as secretary and librarian in 1823.

The art historian N. L. Høyen also took a critical line against the use of motifs from Norse mythology. On June 28, 1821, Høyen addressed the student association in defense of his postulate that Norse mythology was of no benefit to art.

The president of the Academy of Fine Arts, Denmark’s Crown Prince Christian (VIII) Frederik, also took part in the dispute, here on the side of Norse mythology. I 1819, the philologist and archaeologist Finnur Magnússon, himself an eager contributor to the public debate, was hired by royal command as an instructor in Norse mythology and literature at the Academy of Fine Arts. Since 1814, the Academy’s professor of history had already been bound by royal decree to include topics drawn from Norse mythology in the curriculum. This was intended to provide students with the requisite basic knowledge of the literature, legends, and figures of the past, along with archaeological discoveries to date. Furthermore, efforts were made to have Johannes Wiedewelt’s 1780s illustrations to Johannes Ewald’s tragedy Balders død [The Death of Balder] (1770, printed in 1775) engraved in copper, so as to widen familiarity with the gods and heroes of the North.

Thorvaldsen is drawn into the feud

At the height of the mythology dispute, both Finnur Magnússon and Torkel Baden appealed to alleged statements by Thorvaldsen as trump cards for their positions. Magnússon reported a conversation that he had had with the great sculptor on the subject—unprovoked, as he emphasized: “Objections have been made to unsightly elements in Freya’s team of beasts [i.e., the cats to which her car was harnessed], and at first glance these do not seem groundless; but one of the greatest artists of our land and age, namely, Thorvaldsen, declared to me orally, and without any prompting from my side, that he did find that objection groundless. A soulful artist would know how to portray Freya’s cats with beautiful tiger-like forms, and moreover with a character of a sort that could interest a thinking onlooker.”

In an attempt to refute this claim, Baden stated that it was only out of politeness that Thorvaldsen had suggested transforming Freya’s cats into tigers, and that “Thorvaldsen would not have been Thorvaldsen had he meddled with such trifles.” On December 16, 1820, in the same journal, Magnússon repeated that Thorvaldsen had incontrovertibly acknowledged—as had C. W. Eckersberg, another great artist of the day—that it was of value for “young artists-in-training” to acquaint themselves with Norse mythology. Baden’s trump card next came in the journal Nyeste Skilderie af Kjøbenhavn, whose title page bore the headline Thorwaldsens dom over den nordiske Mythologie [Thorvaldsen’s verdict about Norse mythology]. Here Baden cited Thorvaldsen as having declared that he would never concern himself with the Norse gods: “When Thorvaldsen saw Abildgaard’s sketch, which portrays the man licked forth from the stone [by the] cow, he said: ‘How exquisite is that man’s form! But it deserved a better pedigree. O cold North! who lets the animals’ master [humanity] be fed by animals, who lets the man who raises himself toward the heavens be fed by the stooping cow, the wisest creation by idiocy itself. And should the South deny me shelter, nay it is for Thee I long—it is to the East that I journey. Here Moses introduces God as saying: Let us make a man after Our image, after Our likeness. It is in this way that the sculptor sets to work when he seeks to produce something that corresponds to the ideal that floats before his eyes. God is his own ideal. (See Mengse’s classic essay on beauty and taste in works of art.) In Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam we admire, if not the highest culmination, which no mortal can achieve, but the strength of the thoughts and their towering flight.”

For his part, Magnússon publicly cast doubt on this claim. That led Baden to reveal his source: it was the floral painter C. D. Fritzsch, Thorvaldsen’s friend from his student days at the Academy, to whom the sculptor had said these words. Baden then repeated once more that Thorvaldsen would not have been the great artist he was if he had been capable of judging otherwise.

It was these exchanges, in all likelihood, that prompted the Crown Prince to ask Thorvaldsen for a clear statement of support for the usability of Norse mythology in art (and thus for the fatherland) one year later. During that same year, a competition was announced with the aim of advancing the cause of Norse mythology; and this became the occasion for the Crown Prince’s blunt request to Thorvaldsen to send drawings with motifs from Norse mythology to himself or to the Academy of Arts. The evident purpose of this request was to demonstrate, once and for all, that if even the great Thorvaldsen could see nothing wrong with artistic portraits of the Norse gods and heroes, then all other criticism ought also die down: “I am well aware that there can be no question of you drawing [a submission] for the prize yourself. But it would be crucial for the matter at hand, as well as for the purpose of defending the value of Norse mythology, which has been denigrated so impudently (even though it always can, and should, be of interest, indeed of value, to Nordic artists), if you, assuming you have the willingness and the capacity, would sketch some drawings and send them to me or to the Academy. This would, in addition, silence the persons who, with unmatched shamelessness and mendacity, have put words in your mouth that you have never thought to utter, and which do not resemble your [actual] utterances either.—My aim is simply to allow truth to appear for a day, and to keep evil and partisan bias from attaching themselves to a field where Nordic artists perhaps successfully, and fittingly, could win honor and acclaim.”

At issue, in short, were the honor of the fatherland and the future of art in Denmark. No reply by Thorvaldsen to this forthright exhortation is extant; nor do we have any evidence of drawings being completed or sent. However, a later draft of a letter to Christian (VIII) Frederik does evince a positive attitude toward the artistic use of Norse mythology, albeit in a case other than that of Thorvaldsen himself: “His [namely, the sculptor and Thorvaldsen student Hermann Ernst Freund’s] sketches of representations of Norse mythology [are] highly interesting, and I expect of them something exquisite, for the splendor of our Fatherland and for the increase of its artistic holdings.”

This draft letter, however, was not written by Thorvaldsen himself, but by his friend P. O. Brøndsted. In the final version of the letter, which Thorvaldsen did write himself, the topic goes unmentioned. This suggests that Thorvaldsen had consciously avoided putting any such clear declarations of sympathy into writing. In a different case, in which Thorvaldsen does discuss art grounded in Norse mythology (in a recommendation for the painter Andreas Ludvig Koop, who also worked with Norse mythological motifs), Thorvaldsen expresses praise exclusively for the technical element in the work at hand, passing over its content.

In 1822, Copenhageners could read the following encouraging words in the magazine Aftenblad: “Thorvaldsen also has in mind to model something from the Norse legendarium, which he will then execute in marble himself. This despite the efforts of some to make us believe that Thorvaldsen has roughly the same attitude toward Norse mythology as does the Secretary of the Academy of Fine Arts in Charlottenborg!!”

That Thorvaldsen did not in fact do this was explained away entirely by appeal to his many active projects. And so it was that the uncertainty surrounding Thorvaldsen’s position persisted despite these statements.

Other prominent exhortations

Adam Oehlenschläger and N. F. S. Grundtvig were among the poets and authors who paid literary tribute to the newly discovered epic treasures of Norse mythology. Both Oehlenschläger and Grundtvig urged Thorvaldsen to produce works of art with motifs drawn from Norse mythology. Oehlenschläger did so in the festive address to Thorvaldsen that he delivered during a sumptuous celebration in the sculptor’s honor held at Copenhagen’s Skydebanen [the Royal Shooting Range of the Royal Shooting Society] on 16.10.1819: “Create what you wish, what the spirit prompts you; who would dictate subjects to a genius? Though I do have one prayer, which I trust most others share: Give thought at times to the North’s ancient race of gods, to the first noble ideas of a people from whom you descend! Like the spirits of Fingal and Ossian, they waft in the sky, waiting only for you in order—to put it Homerically—to dwell again on earth, and be granted form and life. Norse mythology is closely bound to the creative arts; so perhaps it is to the heroes from whom you are descended that you owe the fact that you are a sculptor. Much later, perhaps never, shall you see the Fatherland again; may such works then be a comfort to you! And when in your workshop you sculpt Thor with his hammer, Freyr with his Gerda, Bragi with his harp, Idun with her basket of apples, then you will always feel that you are in Denmark once more.”

Presumably, Oehlenschläger’s wish that the Norse gods and heroes should “dwell” and live again on earth is not only a metaphor for the hope that they would be granted new “life” by virtue of Thorvaldsen’s statuary, but also a reference to the German philosopher and author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who had contributed to the mythology dispute on behalf of the ancients by writing that the Norse gods and heroes were still covered in the mists of the grave. The aforementioned Baden had cited precisely this line from Goethe in his piece Om den nordiske Mythologies Ubrugbarhed for de skjønne Kunster [On the Unusability of Norse Mythology for the Fine Arts]: “The gods of the Greeks and Romans live; they [were] transmitted directly from an actual life among the people into art. As for the Norse and Indian divinities, on the other hand, to include them in poetry, we must revive them from the dead; but the effort to dispel the mists of the grave from them has not yet succeeded.”

Grundtvig, for his part, entreated Thorvaldsen at the dedication of the studio built for the sculptor in the garden of Nysø manor. The studio was dedicated on 24.7.1839, and Grundtvig dubbed it “Volund’s Workshop.” In an excerpt from the poem cited in an article by Grundtvig, the studio is called a “cottage,” and Thorvaldsen is identified with Volund the goldsmith:

We built him a cottage on Denmark’s coast

In a linden glade, with fair wreaths of flowers.

Will Volund Wingsmith bring his art within

And conjure the Æsir’s shining hours?

Grundtvig prefaced his recital of this poem by issuing a somewhat sarcastic apology for speaking of the Norse legendarium in the first place: “Though I have been asked to recite the song as well, I do not have the courage to do so without a little preface, which could defend or even apologize to people for my reference to the myths of the North, which still sound Chinese to most ears, though all the Latin ghosts, with Bacchus and Venus, are either greeted as household gods or known as garden sprites.”

Put briefly, the challenge for Norse mythology was not simply that it was pagan and, unlike classical mythology, had not been elegized by Winckelmann or Goethe, let alone used as a prototype, to a greater or lesser degree, ever since the Renaissance. The difficulty is also that, qua cultural sphere, Norse mythology was newly discovered and relatively unknown to archaeology and other scholarly fields. Crucial to the formal-visual language of Neoclassicism was the possibility of verifying the correctness of depictions of various historical periods, and in borrowings from the statues, coins, reliefs, etc., of classical antiquity. The story of Thorvaldsen’s mentor, the archaeologist Georg Zoëga, correcting some of Thorvaldsen’s earlier works in Rome because they deviated from their ancient prototypes, and the tale of the renowned 1803 model of Jason with the Golden Fleece, cf. A52, which the sculptor himself held were copied all too faithfully from ancient templates, are both anecdotes that, true or not, indicate in part the age’s demand for exactness and loyalty with respect to classical sources, and in part the artist’s own need for creative freedom in relation to a known original.

The pressure on Thorvaldsen lasted years, and only increased with time. Thorvaldsen’s assistant, the sculptor Hermann Ernst Freund, attempted to persuade him, at the behest of Jonas Collin and others, to produce works drawn from Norse motifs: “At the outset he stated that he would produce a Thor; but later he always excused himself on account of his many tasks,” Freund wrote to Collin in 1822.

As early as 1804, Thorvaldsen’s former patron Herman Schubart had suggested that Thorvaldsen use Norse motifs for the statues in the new Christiansborg Palace, for which the architect C. F. Hansen was responsible: “Perhaps you would like to acquaint yourself with our old and interesting Scandinavian mythology. If so, then do write to our friend Stub, and ask him to send you by courier the part of Mallet’s Danske Historie [Danish History] that contains the Edda, a veritable masterwork. This book is found in my collection, and I will write to good Stub to send you whatever you need. Still, this idea about our Scandinavian mythology is only an undigested thought, which you by no means must accept, if you think better of it. Just consider that this could come to be a work that can make your talent immortal.”

Thorvaldsen’s own position

We have no extant reply to Schubart by Thorvaldsen. But Schubart’s next letter makes the outcome clear—Thorvaldsen wished to work on the basis of classical myths known to all: “Your thought about the immortals whom you will render eternal at the gate of Christiansborg Palace is supremely fitting. It is better than if you had taken something from Scandinavian mythology, which is only poorly known; whereas everyone knows and loves Minerva, Jupiter, Nemesis, and Hercules. In Rome, moreover, one can hardly work on anything other than Roman and Greek gods and heroes.”

Moreover, a letter sent by Thorvaldsen to C. F. Hansen indicates clearly that the sculptor’s view was unchanged two years later. In this letter, which he wrote and sent himself, Thorvaldsen announces that “in order to fulfill the high commission’s demands for allegorical subjects in the medallions for the palace, I intend to make use of Greek mythology, inasmuch as it is the most cultivated and consequently the most worthy for art ...” [emphasis added]

It thus seems entirely reasonable to assume, not least on the basis of the statements above, that Thorvaldsen had no urge to make use of Norse mythological motifs in his own work. First and foremost, we find no works with such motifs at all in Thorvaldsen’s œuvre. His debt to the ideals of Neoclassicism and the theories of Winckelmann, perhaps along with business instincts befitting a sculptor of international stature, weighed more heavily on Thorvaldsen than did exhortations from the fatherland. As early as 1804, the Danish sculptor seemingly preferred to renounce his citizenship than to return home to Denmark, where his prospects for making a living as a sculptor were dim indeed. Already at that early point, it was clear that European Neoclassicism was where Thorvaldsen’s future lay. To have embarked on projects drawn from Norse myth would not only have portended a break with the ideals of Neoclassicism as Thorvaldsen clearly understood and applied them, but would also have meant a more restricted and less prosperous audience; it would have meant that he would have had to start from scratch in becoming conversant in the symbolism, drapery, weapons, tools, and architecture of another legendarium; and it would have meant doing so at such an early stage, in which what mattered most was being discovered and set on firm footing.

What is more, the vocabulary of classical antiquity is one that Thorvaldsen had learned to master completely—by virtue of his early education, his later studies, the help of Georg Zoëga, and his own and others’ collections of objects from antiquity—as well as to scramble it in order to generate new meanings. In short: Thorvaldsen had little incentive to incorporate the Norse legendarium into his work.

Thorvaldsen and Thor: the stance softens

Nevertheless, as mentioned in the introduction, there are four extant drafts of Thorvaldsen’s own coat of arms, all of which depict a standing or sitting figure that has been identified—on the basis of, among other things, the memoirs of Thorvaldsen’s valet C. F. Wilckens—as Thor. These drafts bear clear reference not only to Norse mythology, but also to Thorvaldsen’s last name, his Nordic roots, and his Icelandic ancestors on his father’s side.

In several cases, admirers of both Thorvaldsen and Norse mythology studied the sculptor’s family tree and proceeded to claim that he was descended from Eric the Red (born c. 950), or from an Icelandic king. Thorvaldsen was also elegized by contemporaries as his etymological brother Thor, the Norse thunder-god, who, like the sculptor, could work wonders with his hammer. This comparison can be found in many places in the preserved sources. Even Baroness Christine Stampe, a friend to Thorvaldsen in the years after his return to Denmark in 1838, called him by this name.

The cultivation of Thorvaldsen’s Nordic roots, of which the interest in family trees is an example, and the comparisons of the sculptor to Thor, Volund the Smith, and other heroes from the Norse legendarium, can be understood in concert as an attempt to incorporate Thorvaldsen into the Danish project of national self-promotion, whereby his international star status would rub off on the fatherland.

It seems likely that such massive national hero-worship ultimately flattered Thorvaldsen so much that he adopted the comparison himself, and so threw a crumb, so to speak, to the eager advocates of Norse mythology. This interpretation is supported by a report of Christine Stampe, who sketched Thorvaldsen’s work on the self-portrait statue Bertel Thorvaldsen with the Statue of Hope, Nysø1. Her comparison of the Norse god to Thorvaldsen worked without question in the sculptor’s favor: “While he labored on his own statue, for which I had sewn him a kind of blouse in accordance with his own drawing, he teasingly fastened the belt firmly, and said: ‘Now I am strong. This is what Thor did when he used [his] powers. They have called me Thor: one Thor smashes, the other creates.’”

Draft drawing of a coat of arms and seal with a standing male figure holding what may be a hammer in his hand, C386v. While the exact date of this drawing is unknown, it has been assigned the approximate date 1827.

This brings us back to the unfinished draft of Thorvaldsen’s own coat of arms, which seems to articulate his self-understanding as a powerful sculptor with Norse roots and a mythical name. C. F. Wilckens described how Thorvaldsen, like a hammering Thor, turned out draft after draft of the coat of arms. Rikard Magnussen, who wrote a 1939 article about “Thorvaldsen og Norden” [Thorvaldsen and the North], claimed that it was solely the coincidence of names that led Thorvaldsen to draw a Thor in the drafts. Nevertheless, it is quite likely that the whole absorbing nationalization of Thorvaldsen also played a role in this context. Wilckens reports that Thorvaldsen had already begun sketching a coat of arms in Rome many years before. This refers presumably to the drafts dated c. 1827, C559a, reproduced above, and C560r, reproduced below. Possible occasions for these were Thorvaldsen’s ruminations on where he should place his collections, and his subsequent preoccupation with his own identity and affiliations. The matter became unavoidable, however, when on 18.11.1839 Thorvaldsen was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog. This award required that Thorvaldsen draw a coat of arms and choose a personal device, so that in accordance with tradition, a coat of arms could be produced and hung in the palace church at Frederiksborg Palace.

“I know of no other family heraldry than a T, which was my father’s old seal,” Wilckens reported Thorvaldsen as having said. Wilckens added: “At last he took up his pencil, and on various sheets of paper a Thor emerged with his hammer, with one or another small variation in placement. Afterwards he began working on the personal device, which he similarly wrote on many sheets of paper; it converged on the motto Kjærlighed til Fædrelandet [Love for the Fatherland]. When Oehlenschlæger visited Thorvaldsen one day, the sculptor showed him his draft coat of arms, which Oehlenschlæger thought well of. ‘But I do not think much of your device,’ said Oehlenschlæger. ‘Yes, let me hear your opinion,’ Thorvaldsen asked. ‘You are a man of freedom,’ Oehlenschlæger replied, ‘and so you should use the words “Freedom and Love for the Fatherland.”’ ‘You deserve thanks for that!’ Thorvaldsen responded. ‘You know me precisely, and you know that it was to preserve my freedom that I did not want to get married. Now it shall be as you say.”

Draft of Thorvaldsen’s Coat of Arms and Device, c. 1839, C559b. According to Wilckens, the animal skin (presumably a bearskin) and hammer are associated with Thor. Draft of Thorvaldsen’s Coat of Arms and Device, c. 1839, C559b. According to Wilckens, the animal skin (presumably a bearskin) and hammer are associated with Thor. |

Draft of Thorvaldsen’s Coat of Arms, c. 1827, C560r. There is nothing in this sketch indicating unmistakably that the figure represented is a Thor. Draft of Thorvaldsen’s Coat of Arms, c. 1827, C560r. There is nothing in this sketch indicating unmistakably that the figure represented is a Thor. |

With this, Oehlenschläger was presumably referring not simply to Thorvaldsen’s unmarried status, but rather to his continuing insistence on artistic freedom in relation to his works and place of residence. It is also probable that this declaration of freedom went even deeper, and applied also to the political-civil freedom that had emerged in the wake of the struggles that led to the French Revolution.

After Thorvaldsen’s death, H. W. Bissen completed the coat of arms following Thorvaldsen’s sketches, and the result was hung in Frederiksborg Palace. This is a gouache of the coat of arms produced in 1844 by herald painter Ole Larsen, N152.

Beyond the drafts of his coat of arms, Thorvaldsen’s previously mentioned self-portrait statue Thorvaldsen with the Goddess of Hope, Nysø1, arguably also includes conscious associations with the god Thor and his hammer and belt; cf. the anecdote related above. The hammer, after all, is nothing other than the classic symbol of the art of sculpture (together with, among other things, the chisel, which Thorvaldsen is depicted as holding in his other hand). What is more, the statue of The Goddess of Hope, which Thorvaldsen portrayed himself as working on, has a marked classical-antique appearance, inspired by archaic art and Thorvaldsen’s Restoration of the Sculptures from the Temple of Aphaia for Ludwig I of Bavaria. There is, then, no reference at all to Norse mythology here, apart from what can be attributed to the belt and the hammer.

|

|

Bertel Thorvaldsen with the Goddess of Hope, Nysø1 - a resurrected Thor, or just a sculptor with his artwork, his inspiration, and his tools?

A possible closer look at Thorvaldsen’s motives can be provided by introducing another alleged Thorvaldsen quotation. In her memoirs, Christine Stampe recounts the reason Thorvaldsen gave for not wishing to produce works of art inspired by the Norse legendarium. According to Stampe, Thorvaldsen gave this reason while she, at Oehlenschläger’s behest, was reading aloud to Thorvaldsen about Norse gods and heroes in order to pave the way for him to use Norse themes in his work: “It is cold, so these heroes had to dress warmly; but the naked body is the most beautiful, it is the clothing of Our Lord. And he added numerous other reasons, which I cannot remember. The truth is that I continued to believe that it was best for him to follow his own inclinations, as long as he was simply working, and that was what I animated him to do; what he did was all the same to me.”

This paean to the naked human body as a motif that is especially worthy of depiction fits smoothly with the ideals of Neoclassicism, in which the beauty of the body and its representation in art are based on the notions of the beauty of each individual part and the harmony of their composition. According to Winckelmann, the temperate skies of Greece had salutary effects on the human body, and thereby also on art, culture, social relations, and philosophy. To this the Nordic winter cold, which forced human beings to clothe themselves in fur, hides, and thick wool cloth, could hardly compare.

Thorvaldsen’s extensive book collection contains six books about Norse mythology. These indicate that Thorvaldsen was not, or at least did not need to be, as ignorant about the matter as certain anecdotes suggest.

For example, Magnussen, op. cit., p. 57, cites a conversation between Oehlenschläger and Thorvaldsen in which the the sculptor disclaimed Norse motifs on the grounds that he did not know how the figures would need to be draped. Reportedly, the Swedish sculptor Bengt Erland Fogelberg later showed him his statue of Thor, at which sight Thorvaldsen declared: “So that is what he looks like!”

On this basis, Magnussen concluded that if Thorvaldsen had only known how to do so, he probably would have done so. The sticking-point, in short, was simply Thorvaldsen’s lack of relevant theoretical knowledge. In all likelihood, this is at most a qualified truth. In reality, Stampe’s report of Thorvaldsen’s reverence for the naked human body as an ideal, and the general cultivation by Neoclassicism of Greek antiquity as the source of the beautiful, the noble, and the good, were probably much more significant to Thorvaldsen.

The six books on Norse mythology that have been preserved in Thorvaldsen’s collection are the following:

- Jacob Bærent Møinichen, Nordiske Folks Overtroe, Guder, Fabler og Helte indtil Frode 7 Tider i Bogstav=Orden [The Superstitions, Gods, Fables, and Heroes of the Norse People Until the Age of Frotho VII, in Alphabetical Order], Copenhagen 1800, M509.

- Edda eller Skandinavernes hedenske Gudelære [The Edda, or the Scandinavians’ Pagan Pantheon]. Translated by R. Nyrup, Copenhagen 1808, M510.

- Frederik Sneedorff Birch, Udsigt over den nordiske Mythologi [Survey of Norse Mythology], Copenhagen 1834, M511.

- Finn Magnusen, Bidrag til nordisk Archæologie meddeelte i Forelæsninger ved Finn Magnusen [Contributions to Norse Archaeology, Presented as Lectures by Finn Magnusen], Copenhagen 1820, M512.

- Nordisk Tidsskrift for Oldkyndighed [Nordic Journal of Antiquities], vols. 1-2, København 1832-33, M513

- Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae, Danmarks Oldtid, oplyst ved Oldsager og Gravhøie [Denmark’s Ancient History, Elucidated by Archaeological Specimens and Burial Mounds], Copenhagen 1843, M514.

Of these, four were published during or after the 1820 peak of the mythology dispute; and it is probable that Magnússon had himself presented Thorvaldsen with a copy of his book. Most of the books are not signed by Thorvaldsen, but he did write his name as “Albert” in those by Frederik Sneedorff Birch and Jacob Bærent Møinichen, indicating that the earlier of these (Møinichen’s book, published in 1800) had only came into Thorvaldsen’s possession quite late, presumably as part of the intensifying pressure on the sculptor.

Summary

Thorvaldsen appears to have found it appropriate, and perhaps even welcome, to be celebrated as a Nordic or Norse figure, so long as his works were not interfered with. His donation of a version of Brahetrolleborg’s Baptismal Font, cf. A555,1, A555,2, A555,3, A555,4, to a church in the town of Miklabæ in Blönduhlið settlement—his father’s birthplace—supports the assumption that Thorvaldsen valued his Icelandic origin highly.

Ironically enough, it was the exiled author and critic Malthe Conrad Bruun who described Thorvaldsen’s accomplishment most clearly with national-patriotic eyes: J’ai très-souvent desiré, en qualité de compatriote, d’avoir une occasion de Vous temoigner ma sincère admiration et la joÿe de voir un Scandinave ramener en Italie le veritable gout de la sculpture antique. Ce sera la plus belle page de ma Géographie Universelle que celle où je pourrois dire que les Dieux de Rome ou plutot de la Grece sont ressuscités par le ciseau d’un enfant d’Odin.

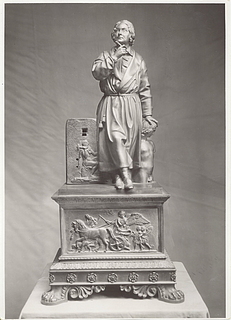

In the 1830s, the Italian sculptor Alessandro Puttinati produced a portrait of Thorvaldsen in the form of a bronze statuette covered in gold. The statuette represents the sculptor as standing and leaning on a classically-inspired torso of a youth. The relief that appears to the left of Thorvaldsen depicts a sitting man wearing a crown, and holding a hammer in his right hand—most likely a Thor. The runes carved into the relief, as well as Thor himself, serve to refer to Thorvaldsen’s Nordic roots, while the torso of the youth alludes to classical antiquity. With these references, Puttinati sought to create an image of what were regarded as the two main components in Thorvaldsen’s idiosyncratic artistry, corresponding to the remark in Malthe Conrad Bruun’s letter cited above: les Dieux de Rome ou plutot de la Grece sont ressuscités par le ciseau d’un enfant d’Odin. For more on this statuette, see Puttinati’s biography.

When we put all of these statements together—including the citations from the mythology dispute—what emerges is the image of an internationally based and thoroughly consistent sculptor who held fast to classical antiquity (and Christendom too, to a lesser extent) as his source of motifs. Whether Thorvaldsen truly did condemn Norse mythology as unusable and degraded, as C. F. Høyer postulated, cannot be established firmly. On the contrary: it seems likely that Thorvaldsen saw nothing wrong with the next generation entering a field in which, in the Crown Prince’s words, they could perhaps win honor and renown. Because he himself had cornered the market, so to speak, on classical mythological motifs, Thorvaldsen was perhaps well aware that it could be difficult for others to make a mark there. In any event, despite numerous entreaties calling for him to take a stand on Norse mythology, there is no evidence that Thorvaldsen saw it as his role to become a public arbiter of the matter.

References

- Ludvig Baden: L. Jakobsens Forsvar mod Hr. Professor Finn Magnussen, Copenhagen 1820.

- Torkel Baden: Et Par Ord til Beslutning om den nordiske Mythologie, Copenhagen 1821.

- Torkel Baden: Om den nordiske Mythologies Ubrugbarhed for de skjønne Kunster, Copenhagen 1820.

- H. R. Baumann: Hermann Ernst Freunds Levned ved Victor Freund, Copenhagen 1883, p. 266; see also p. 141, which discusses Thorvaldsen’s readiness to sculpt a statue of Thor.

- C. F. Høyer: Tilegnet Det Kongelige Kunstakademiets Medlemmer og unge Kunstnere, Copenhagen 1821, Thorvaldsen’s Book Collection, M875,10.

- L. Jacobsen: Professor Finn Magnussens Beviis for, at vore Kunstnere ved Rejser til Island kunde naae det samme som ved at rejse til Italien eller Rom: Med Anmærkninger af L. Jacobsen, Hirschholm 1820.

- Hans Kuhn: Greek gods in Northern costumes: Visual representations of Norse mythology in 19th century Scandinavia, 11th International Saga Conference held in 2000 at Australian National University, http://sydney.edu.au/arts/medieval/saga/pdf/209-kuhn.pdf.

- Finnur Magnússon: Bemærkninger ved Torkel Badens skrift: Om den nordiske mythologies ubrugbarhed for de skjönne kunster, Copenhagen 1820.

- Finnur Magnússon [Finn Magnusen]: Den Ældre Edda: En samling af de nordiske folks ældste sagn og sange, Copenhagen 1822, vol. 3, p. VII.

- Finnur Magnússon [Finn Magnusen]: Indledning til Forelæsninger over den ældre Edda’s mythiske og ethiske Digte, Copenhagen 1816.

- Finnur Magnússon [Finn Magnusen]: Udførlig erklæring fra Professor Finn Magnusen i anledning af et pseudonymt Flyveskrift, kaldet, Professor Finn Magnussens Beviis for, at vore Kunstnere ved Rejser til Island kunde naae det samme som ved at rejse til Italien eller Rom. Med Anmærkninger af L. Jacobsen, Hirschholm 1820, Copenhagen 1816.

- Rikard Magnussen: ‘Thorvaldsen og Norden,’ in Nordens Kalender 1939, Oslo 1939.

- Anton Raphael Mengs: Gedanken über die Schönheit und den guten Geschmack in der Mahlerey, Orell 1774.

- Jens Møller: Om den nordiske Mythologies Brugbarhed for de skjønne Tegnende Kunster, Copenhagen 1812.

- Nyeste Skilderie af Kjøbenhavn, vol. 17, no. 96 (November 28, 1820).

- Nyeste Skilderie af Kjøbenhavn, vol. 17, no. 101 (December 16, 1820).

- Nyeste Skilderie af Kjøbenhavn, vol. 17, no. 104, (December 26, 1820).

- Nyeste Skilderie af Kjøbenhavn, vol. 17, no. 105 (December 30, 1820).

- Nyeste Skilderie af Kjøbenhavn, vol. 18, no. 31 (April 17, 1821).

- Haavard Rostrup: Billedhuggeren H.W. Bissen, Copenhagen 1945, vol. 2, p. 12, note 72.

- Emma Salling and Claus M. Smidt: ‘Fundamentet: De første hundrede år,’ in Anneli Fuchs and Emma Salling (eds.): Kunstakademiet 1754-2004, vol. 1, Copenhagen 2004.

- Rigmor Stampe (ed.): Baronesse Stampes Erindringer om Thorvaldsen, Copenhagen 1912.

- Thiele IV, 1856, p. 104-05.

- Per Thornit: “Tegn paa udvortes Erkjendelse…”: Bertel Thorvaldsens og H.C. Andersens ordener, [Copenhagen], 1979, p. 28.

- Karsten Friis Wiborg: Fremstilling af Nordens Mythologi for dannede Læsere, Copenhagen 1843, p. xviii.

- C. F. Wilckens: Træk af Thorvaldsens Konstner- og Omgangsliv, samlede til Familielæsning, Copenhagen 1874, p. 138-139; reprinted as Thorvaldsens sidste år. Optegnelser af hans kammertjener, Copenhagen 1973, p. 66-67.

Last updated 13.01.2026