This article describes a set of ten of Thorvaldsen’s most famous sculptures rendered in miniature for use as a table decoration for the Danish royal family. The sculptures were produced by the bronze caster Wilhelm Hopfgarten, and was commissioned by the Danish prince Christian (8.) Frederik. The male figures in the table decoration were subsequently equipped with fig leaves.

Thorvaldsen was already a well-established sculptor, busy with numerous works on commission, when the Danish prince Christian (8.) FrederikI visited his workshopII in Rome for the first time. Christian Frederik and his wife Caroline AmalieIII were then on an extensive Grand TourIV of Europe, and Thorvaldsen’s workshop was one of the first things they saw after arriving in Rome on 23.12.1819V. Thorvaldsen himself was then on a visitVI to Copenhagen; but his workshop remained active in his absence thanks to the productivity of its many employees, who were then working under the temporary managementVII of the sculptors Hermann Ernst FreundVIII and Pietro TeneraniIX.

We have written documentationX that Christian Frederik felt an “indescribable joy” upon encountering Thorvaldsen’s art. We also know that one outcome of this powerful experience is that Christian Frederik had the idea of commissioning ten of Thorvaldsen’s most famous sculptures in miniature to decorate the table at official banquets—as a kind of reminderXI or souvenir, so to speak.

Freund informed Thorvaldsen of Christian Frederik’s idea for the “table arrangement” in May 1820XII. Apparently, however, there was no need to secure Thorvaldsen’s approval of the reproductions, as Christian Frederik by then had already hired Freund and Tenerani to “model the two small figuresXIII”—referring presumably to trial reproductions of two of the sculptures in miniature size, in order to give the prince a concrete sample to evaluate.

At this point, in May 1820XIV, it remained unclear what materials would be used in the production of the figures: there was talk of both marble and alabaster. One year later, however, when Christian Frederik wroteXV from Lucerne to Thorvaldsen, who was then back in Rome, that a gilt bronze model of Shepherd Boy had been sent to him—and that he “could not restrain hiself from commissioningXVI the others as well”—gilt bronze became the material of choice.

Gilt bronze could certainly have been suggested by Thorvaldsen in one of the many conversations he had with Christian Frederik following his return to Rome on 16.12.1820XVII. But perhaps it was Freund or Tenerani, or the Danish royal agent P.O. BrøndstedXVIII, who had imagined as early as in the autumn of 1819XIX that Thorvaldsen’s Shepherd Boy would “turn out beautifully” in bronze.

Hermann Ernst Freund (?) and Wilhelm Hopfgarten, modeled after Thorvaldsen, Shepherd Boy, 1821,

The Royal Danish Collections, Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen, inv. no. 20-64.

The figures for the prince’s table decoration were cast by the German bronze caster Wilhelm HopfgartenXX at Jollage & Hopfgarten, his Roman foundry and chiseling workshop, which specialized in the production of sourvenirs modeled after classical Roman art.

It is difficult to establish which artist was responsible for modeling the miniature versions of Thorvaldsen’s sculptures, as documentation is sparse. At one pointXXI in his biography of Thorvaldsen, Just Mathias Thiele writes that Christian Frederik “appointed Freund” to have the figures be modeled. ElsewhereXXII, however, Thiele states that it was Thorvaldsen’s then-student, the Italian sculptor Pietro GalliXXIII, who had:

“just recently distinguished himself by copying a number of Thorvaldsen’s statues in miniature for Prince Christian Frederik’s aforementioned table service.”

We may perhaps cautiously assume that Freund modeled the first figure, Shepherd Boy, as a sample, while Galli modeled the rest. Judging by the correspondenceXXIV on the subject, Freund did also play a coordinating role in the commission, in which capacity he received ongoing instructions—e.g., to keep pressure on Hopfgarten, to locate miniature pedestals in porphyry, and to arrange the transportation to DenmarkXXV of the bronze figures once completed.

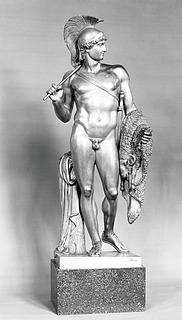

Wilhelm Hopfgarten’s bill to Christian Frederik was for 1380 scudi. The agreed-upon price had been for 100 scudi per bronze figure, but with extra charges for the largestXXVIII figures, namely Jason with the Golden Fleece, Mars Bringing Peace, and The Three Graces. For these Hopfgarten requested 150, 200, and 240 scudi, respectively. Moreover, The Three Graces was unique in being outfitted with a larger, more complex miniature porphyry pedestal with gilt ornaments, for which Hopfgarten requested an additional 90 scudi.

Christian Frederik, however, was unsatisfied with the size of these additions, and proposedXXIX a reduction in price of 80 scudi. The final price that Hopfgarten apparently received was thus 1300 scudi.

Freund likely received a fee for his role in the commission. Pietro Galli, too, received payment, but possibly only in the form of ordinary daily wages.

It is unknown whether Thorvaldsen received some form of royalties for his rights to the sculptures. Presumably, however, he did not.

There also exists an eleventh figure for the table decoration, copied not from a sculpture by Thorvaldsen, but from Pietro Tenerani’s 1816 statue Psyche AbandonedXXX.

The bronze figure of Psyche is not mentioned in the documents surrounding the commission; nor was it put on display at the Academy of Fine Arts’ 1827 exhibitionXXXI in Copenhagen featuring the other ten figures. However, this miniature Psyche came with a miniature porphyry pedestal similar to those of the other ten figures, making it highly plausible that it too was cast and fitted by Wilhelm Hopfgarten and, indeed, commissioned by Christian Frederik as well. If this was the case, then it too would have been produced during the period no earlier than 12.8.1821—no later than 10.5.1825XXXII, as was the rest of the commission.

Pietro Tenerani and Wilhelm Hopfgarten, modeled after Pietro Tenerani,

Psyche Abandoned, 1821-1825,

The Royal Danish Collections, Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen, inv. no. 20-80.

The bronze figures were transported to DenmarkXXXIII in 1825 with the brig St. Croix. They were displayed at the Academy of Fine Arts’ 1827 exhibitionXXXIV in Copenhagen, and were subsequently used as a table decoration for Christian Frederik’s gala dinners.

The bronze figures served not only as an attractive, decorative element in the palace’s table setting, but also presumably played a role as a conversation starter for guests, for whom the figures provided an opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge of contemporary art, of classical mythology, and of course of Thorvaldsen, the hotshot of the day.

Associated with the bronze figures is an old, undated drawing or planXXXV that shows how the figures were placed on the table in composition with candelabras, fruit and flower bowls, and mirror platesXXXVI: The Three Graces was set in the middle of the table on a large, oval mirror plate. It was flanked by Jason and Mars Bringing Peace on round mirror plates, and each of these were surrounded by two candelabras and four figures. The whole arrangement was complemented by fruit and flower bowls, along with 36 pieces of silverware.

Table plan with King Christian 8.’s Table Decoration, mirror plates, candelabras, fruit and flower bowls, and 36 pieces of silverware, undated, The Royal Danish Collections, Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen.

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

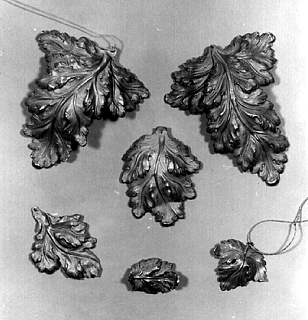

At some point during the history of the table decoration, the nudity of the figures became problematic for the royal host and hostess. When Rosenborg Slot receivedXXXVII the table decoration in 1881, it was accompanied by six fig leavesXXXVIII in gilt metal. These could be fastened with cords to the six male figures in order to cover their indelicate parts.

Fig leaves to attach to the six male figures in the table decoration, The Royal Danish Collections, Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen.

Here it is relevant to cite the Danish miniature and pastel artist Christian HornemanXXXIX, who refers to that period’s wave of prudery, which led to the affixing of fig leaves to many other figures by Thorvaldsen, including the plaster cast of Cupid Triumphant, cf. A22, at the Academy of Fine ArtsXL:

“Your Cupid is one of the most sublime works in the art of sculpture that I have seen; I have never seen anything nobler. What a shame, then, that hypocrisy, pedantry, and a little bit of ignorance have covered his sweet fecund PriapXLI with a hellishly oversized fig leaf made by the plumber on Østergade—you remember him, the one with the pretty sister who died in childbirth. But the worst is that this damned fig leaf makes Cupid’s lower body … look shorter than the upper body, even though it is not. How quickly times have changed—our ladies have become so virtuous that they don’t even dare to look at the most precious thing they have in this world.”

Horneman wrote these lines to Thorvaldsen on 4.5.1829XLII, i.e., only a few years after the arrival of the table decoration in Denmark. It is plausible to assume that the six fig leaves can be dated to the same period, and that it was Christian Frederik himself who had been confronted with “virtuous ladies” and a new, narrow view of art. Perhaps it was even the prince himself who had stopped by the “plumber on Østergade” to commission the fig leaves?

The six fig leaves are more than a mere curiosity in the history of the table decoration. They can also arguably be used to deepen our understanding of the import of Thorvaldsen’s figures—of the messages they convey. For what, after all, are these figures about?

If we dive deep into their origins in Greek mythology, we quickly discover this precise group of figures, when viewed in concert, compose a strong narrative about youth, beauty, peace, freedom, erotic passion, love, and masculine potency.

The Three Graces open the act with youth, grace, beauty, and joy. Their “dinner partners” are the two largest and most masculine men of the company, namely Mars, god of war, who has put down his weapons and comes in peace, and Jason, the hero who has just accomplished his difficult task with bravura.

The lust and daring of youthful masculinity are represented by four young male figures. Cupid, god of erotic passion, meditates on his game of love while the trophies of victory lie at his feet, attesting to the dimensions of human existence that erotic love overpowers (law and order; war; music; poetry). Mercury is about to free his father’s lover from a dangerous monster, while the Shepherd Boy sits calmly, enjoying his free life in an Arcadian idyll. Finally, the handsome youth Adonis consorts with the goddess of love.

Hebe, goddess of youth, serves drinks to the gods (the guests), while the Dancing Girl invites them to dance. Venus, meanwhile, has just won a beauty contest by promising love and passion to Paris, the judge.

In short, these figures singly and together convey a message which, together with the other pleasures of the table—food, wine, fruit, and flowers—emphasizes life-giving, sensuous, and erotic forces. Regarded in this light, Christian Frederik’s table decoration is thus a sensual orgy of golden male and female bodies, whose mythic import and nude sensuality eventually came to be regarded as so obtrusive that measures needed to be taken: six fig leaves were used to moderate the obscenity, or quite literally to cover it up.

Pietro Galli (?) and Wilhelm Hopfgarten, modeled after Thorvaldsen,

Jason with the Golden Fleece and Venus with the Apple, 1821-1825,

The Royal Danish Collections, Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen, inv. nos. 20-66 and 20-79.

In 2015, after having been on display in the Bronze Room at Rosenborg Castle since 1881XLIII, the table decoration was transferred—together with Thorvaldsen’s bronze busts of Christian Frederik and Caroline Amalie—to the Appartement Hall in Christian 8.’s Palace, Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen.

Bertel Thorvaldsen, bronze busts of Christian (8.) Frederik, cf. A197, and Caroline Amalie, cf. A198, 1833, The Royal Danish Collections, Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen.

In addition, the table decoration has been loaned out for the following exhibitions elsewhere:

The table decoration’s Venus and Hebe flank a mirror plate with candelabras and flower bowls at the gala dinner held at Rosenborg Castle on September 14, 2006.

A view down the table with the table decoration’s Mercury in the foreground, followed by Adonis.

“You ought to animate one or another rich personage in Copenhagen to have your Shepherd Boy be cast in bronze. That statue would surely turn out beautifully in that material.”

Letter dated 2.10.1819 from P.O. Brøndsted to Thorvaldsen

“Freund and Thenerani [sic] have each promised that they will begin modeling the two small figures that Your Highness has requested.”

Letter dated 1.4.1820 from Jørgen Koch to Christian (8.) Frederik

“The Prince intends to have a group of ten or eleven figures, two palms in height, modeled in marble or alabaster after your works for a table setting. Presumably he is awaiting your arrival to give serious consideration to something grand: as Mercury and Venus please him so much, he wishes that the latter figure could become part of this table arrangement at a height of two palms. The worst part is that there are very few in Rome who do such work.”

Letter dated between 30.4.1820 and 11.5.1820 from Hermann Ernst Freund to Thorvaldsen

“Although the model of the Shepherd Boy unfortunately did not reach me undamaged, I was nonetheless able to imagine how incomparably the copies of your masterworks will turn out in this gilt material metal, and was unable to restrain myself from commissioning the rest of them. I believe that a porphyry pedestal with gilt ornaments will be the most beautiful, and will write to Freund about the matter.”

Letter dated 12.8.1821 from Christian (8.) Frederik til Thorvaldsen

“His Highness requests that, in the absence of the Agent of the Royal CourtXLV, you ensure that work on the commission from Hopfgarten progresses as much as possible, and that the work be executed with the utmost care.”

Letter dated presumably January-February 1824 from Johan Gunder Adler to Hermann Ernst Freund

“Please speak with him about what should be sent, and take care that Hopfgarten’s works, too … accompany the casts.”

Letter dated 23.3.1824 from Johan Gunder Adler to Hermann Ernst Freund

“At His Highness’s command, I am making use of the return journey of Sir d’Ambrosio, the former Neapolitan chargé d’affaires, to ask you to investigate whether Hopfgarten is making progress with the bronze imitations of your works, which his Highness commissioned from him. The Prince has heard that Hopfgarten is in Berlin, and is worried that this work has stalled for that reason.”

Letter dated 2.6.1824 from Johan Gunder Adler to Thorvaldsen

“At the Prince’s command, I have written to Councillor of State Thorvaldsen to ask him to investigate whether Hopfgarten’s work is progressing, or whether it is true, as rumor has had it, that Hopfgarten is in Berlin.”

Letter dated 2.6.1824 from Johan Gunder Adler to Hermann Ernst Freund

“As before, you have been requested to … keep His Highness informed about how Hopfgarten’s works are progressing, how many of the same have been delivered in good condition, and how much His Highness owes him. Please do not forget the pedestals for the bronze statues; His Highness wishes for them to be finished, or at the very least one of them as a sample.”

“You are requested to treat the transport of His Highness[’s] effects as of vital importance, and to take care that not only the casts are sent, but Hopfgarten’s works as well.”

Letter dated 1.12.1824 from Johan Gunder Adler to Hermann Ernst Freund

“I also await, with genuine pleasure, Hopfgarten’s beautiful imitations of your statues in bronze—which after all have your approval.”

Letter dated 26.2.1825 from Christian (8.) Frederik to Thorvaldsen

“Bronze and marble figures for His Highness Prince Christian”

Shipment manifest 2.7.1825 from Hermann Ernst Freund to Thorvaldsen

“Hopfgarten’s items are completed and well conserved, and one of these days I will busy myself with having them paid for.”

Letter dated 25.10.1825 from Johan Gunder Adler to Hermann Ernst Freund

“In my last letter, I wrote to you that I would undertake to meet Hopfgarten’s demands; and although I am still missing the information I ought to have from Brøndsted, I nevertheless wish to resolve the matter in accordance with His Royal Highness’s wishes. Hopfgarten’s bill is for 1380 scudi. The Prince believes that 200 scudi is too much for Mars, and similarly that 150 is a high price for Jason, particularly given that the agreement was actually for 100 scudi per piece durch die Bank [across the board]—though I do recall that Hopfgarten did insist on an extra charge for the Graces, Mars, and Jason; but the idea was not that he should receive double pay [for these]. —Moreover, [Hopfgarten] has calculated 90 scudi for the pedestal for the Graces; but the Prince holds that this should be included in the 40 scudi listed on your bill for the porphyry block. Finally, [Hopfgarten] owes some compensation for the damage suffered by the Shepherd Boy on the journey, since that was due to how it was packed. —Given all of these circumstances and conditions, I cannot simply pay Hopfgarten’s bill as it stands; but I believe I have made him a decent offer, inasmuch as I have written to him with the daily mail, suggesting that he reduce the bill by a mere 80 scudi. I hope that he accepts this. Accordingly, I attached to the letter a bill of exchange for 1300 scudi at Torlonia. I ask that you help to resolve this matter and support my proposal.”

Letter dated 15.4.1826 from Johan Gunder Adler to Hermann Ernst Freund

Last updated 20.06.2016

The Danish prince Christian (8.) Frederik.

On this see the Related Article Thorvaldsen’s Workshops.

The Danish princess Caroline Amalie.

This was a grand tour to Germany, Italy, Switzerland, France, and England, lasting from May 21, 1818 to August 26, 1822; cf. Fabritius, Friis, and Kornerup (eds.), op. cit., 1976, pp. 611-613.

See also the documents related to the topic Christian 8.’s Journey Abroad 1818-1822.

See the Archives’ Thorvaldsen chronology, under the dates 23.12.1819 and 25.12.1819

See the Archives’ Thorvaldsen chronology, under the dates 14.7.1819 and 16.12.1820.

See the Archives’ Thorvaldsen chronology, under the dates 14.7.1819 – 16.12.1820.

The Danish-German sculptor Hermann Ernst Freund.

The Italian sculptor Pietro Tenerani.

Cf.:

See also Thiele III, op. cit., p. 98 (“…the art-loving prince sought to retain an impression of our artist’s studio in the form of a number of smaller copies”).

Cf. the letter dated between 30.4.1820 and 11.5.1820 from Hermann Ernst Freund to Thorvaldsen.

Cf. the letter dated 1.4.1820 from Jørgen Koch to Christian (8.) Frederik.

Cf. the letter dated between 30.4.1820 and 11.5.1820 from Hermann Ernst Freund to Thorvaldsen.

Cf. the letter dated 12.8.1821 from Christian (8.) Frederik to Thorvaldsen.

See under no later than 12.8.1821 in the Archives’ Thorvaldsen chronology.

See under 16.12.1820 in the Archives’ Thorvaldsen chronology, as well as the references to Christian (8.) Frederik between 16.12.1820 and 7.4.1821, inclusive.

The Danish royal agent, archaeologist, and philologist P. O. Brøndsted.

Cf. the letter dated 2.10.1819 from P.O. Brøndsted to Thorvaldsen.

The German bronze caster Wilhelm Hopfgarten.

Cf. Thiele III, op. cit., p. 98.

Cf. Thiele III, op. cit., pp. 155-156.

The Italian sculptor Pietro Galli.

Cf. the documents relating to the topic Christian 8.’s Table Decoration.

On this see the Related Article Transportation of Thorvaldsen’s Artworks to Copenhagen, 1825.

See the Archives’ Thorvaldsen chronology, under the dates no earlier than 11.5.1820 – no later than 12.8.1821.

See the Archives’ Thorvaldsen chronology, under the dates no earlier than 12.8.1821 – no later than 10.5.1825.

The height of the figures without their pedestals is as follows:

Cf. the letter dated 15.4.1826 from Johan Gunder Adler to Hermann Ernst Freund.

Pietro Tenerani, Psyche Abandoned, 1816, marble, Gallery of Modern Art, Florence.

On this see the Related Article Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen, Exhibitions. I would like to thank Peter Kristiansen, Curator at Rosenborg Castle, for this information.

See the Archives’ Thorvaldsen chronology, under the dates no earlier than 12.8.1821 – no later than 10.5.1825.

On this see the Related Article Transportation of Thorvaldsen’s Artworks to Copenhagen, 1825.

On this see the Related Article Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen, Exhibitions. I would like to thank Peter Kristiansen, Curator at Rosenborg Castle, for this information.

My thanks to Peter Kristiansen, Curator at Rosenborg Castle, for this information and the accompanying pictures.

The table decoration contained the following items produced at the bronze foundry Thomire à Paris in France in 1822; cf. Jens Gunni Busck, op. cit.:

The table decoration was purchased by the brewer Carl Jacobsen (1842-1914) from the estate of Caroline Amalie in 1881, and was donated to Rosenborg Castle; cf. Bering Liisberg, op. cit.

I would like to thank art historian Ernst Jonas Bencard for noticing and pointing out these fig leaves.

The Danish miniature and pastel artist Christian Horneman.

Cf. the Related Article Commission for the Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen.

A noun derived from Priapus (gr. Priapos), a Greco-Roman fertility god who sported a grotesquely large, erect penis.

Cf. the letter dated 4.5.1829 from Christian Horneman to Thorvaldsen.

The table decoration was purchased by the brewer Carl Jacobsen (1842-1914) from the estate of Caroline Amalie in 1881, and was donated to Rosenborg Castle; cf. Bering Liisberg, op. cit.

My thanks to Peter Kristiansen, Curator at Rosenborg Castle, for this information and the accompanying pictures.

The Danish royal agent, archaeologist, and philologist P. O. Brøndsted.