A Dispute between two Women about Thorvaldsen and his Posthumous Reputation

- Kira Kofoed, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2019

- Translation by Karen Jelved, Andrew D. Jackson

The basis of this article is the way two women saw and used Thorvaldsen. Both the painter Bolette Puggaard and Baroness Christine Stampe were born into the upper middle-class and achieved financial independence through marriage. They were both close to Thorvaldsen and tried, each in her own way, to nurture and emphasize aspects of the sculptor that they saw as essential qualities of the time. The objective is to place Thorvaldsen in the politics of his time as a champion of liberty and a lovable genius, respectively.

- 1. Thorvaldsen as a Historiographic Figure

- 2. Stampe and Puggaard — Monopolization and Partial Oblivion

- 3. “Approximately the Same Relation as Mrs. Stampe”

- 4. Background, Common Features, and Fundamental Differences

- 5. Solicitude and Admiration

- 6. The Struggle for Thorvaldsen’s Presence

- 7. Pragmatist or Revolutionary?

- 8. Thorvaldsen and his Art as Political Statement

- 9. Bolette Puggaard’s Happening and its Context

- 10. Summary – the Ethical Genius and the Reckless Revolutionary

- 11. References

Thorvaldsen as a Historiographic Figure

It is well known that Thorvaldsen was a superstar in his own age, and several people crowded round him. There were many reasons for this popularity ranging from common curiosity and general star-worship to a sincere interest in art and friendship — occasionally combined with a need for an influential torchbearer for a personal, political, or national cause. Controversies in the press, songs of tribute, private letters, and later memoirs testify to Thorvaldsen’s popularity and to the many different views of him and his museum.

This article investigates two trends in the contemporary worship and use of Thorvaldsen. It takes two women as its starting-point — Baroness Christine Stampe, of upper middle-class background, and Bolette Puggaard, a painter who was married to a merchant. Both women, consciously or unconsciously, wished to create a contemporary and posthumous reputation for Thorvaldsen as a figure of national unity. The two women can be seen as representatives of two distinctive and partly opposite views, each trying to recruit Thorvaldsen — willingly or unwillingly — and they can serve to illuminate Thorvaldsen’s political navigation at a dangerous time when absolute monarchies were crumbling.

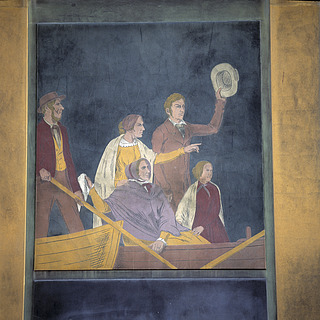

Sonne’s frieze showing Thorvaldsen’s landing in 1838; part of panel 1 on the northwestern façade of the museum.

A satirical article in Corsaren 1847 in 1847, which criticizes the painter Jørgen Sonne’s frieze on the outer wall of Thorvaldsen’s Museum, pays special attention to three people, who played particularly important roles in relation to Thorvaldsen. They are: academy secretary, counsellor, and author Just Mathias Thiele, who wrote the first two (and still the most comprehensive) biographies of Thorvaldsen and his works; the above-mentioned Baroness Christine Stampe, who became Thorvaldsen’s energetic protector and hostess after his return from Rome in 1838; and finally, the self-made Danish merchant Hans Puggaard, the husband of Bolette Puggaard.

Describing the first scene in the frieze that shows Thorvaldsen’s landing and his reception by the Academy of Art, the article in Corsaren says:

[...] None of them, however, stretch out their arms to such an — we might almost say — unbecoming length as Counsellor Thiele, whereby the artist undoubtedly has wanted to symbolize that the said counselor has best managed to make capital of Thorvaldsen’s fame for himself and ensured his own immortality. To use a vulgar expression, he is trying to pickpocket Thorvaldsen’s reputation.

The description then moves on to the artists and famous people in small boats as parts of the reception:

[...] After these [artists] various famous men and women follow in boats: first of all Baroness Stampe with her Baron, who waves his hat in sincere enthusiasm for art. The Puggaard family follows behind them. We honestly admit that we cannot sympathize with the artist in his decision to place Mr. Puggaard here; it is, of course, true that Puggaard is a famous man, but the corn trade does not really have much to do with art. [...]

Hans, Marie, Bolette, and Signe Puggaard; fifth panel facing the canal.

A boatswain from Puggaard’s boat who is restrained by the seated Baroness Christine Stampe. Also Baron Henrik Stampe and their daughters Elise and Jeanina: fourth panel.

Although the article criticizes Thiele’s exploitation of Thorvaldsen’s fame, it does not directly question the justification of Christine Stampe’s presence even though the family did not take part in the reception. It does, however, sneer indirectly at Henrik Stampe’s naïve and perhaps cuckold-like tribute to Thorvaldsen, who was his wife’s friend to a degree that occasionally aroused his jealousy. Finally, the article declares it a mistake to allow Hans Puggaard, being as it were a nouveau-riche upstart in the corn trade, to take second place in relation to Thorvaldsen, i.e. just behind Stampe.

In the same article, Sonne is blamed for treating the royal official Jonas Collin unfairly. In short, according to the writer of the article, some have undeservedly received too much attention, others too little. Already at the time, it was well known that the frieze was not a true picture that documented the reception faithfully, but rather a careful historical and — one might add — political construction. The presentation and consolidation of various people’s relation to and possibly selfish exploitation of Thorvaldsen was already widely discussed at the time, and Sonne’s frieze, as the quotation shows, was a pointed example of this.

Stampe and Puggaard — Monopolization and Partial Oblivion

It is not only in Sonne’s frieze but also in later times more generally that Thorvaldsen’s connection with the Stampe family at Nysø Manor near Præstø has dominated the account of the sculptor’s last years. This means first and foremost Christine Stampe as Baron Henrik Stampe shortly after their wedding became mentally ill, cf. both his and her biographies. She first got to know Thorvaldsen well during the summer of 1839, i.e. after his re-establishment in Denmark, but she had met him before during at least one journey to Italy.

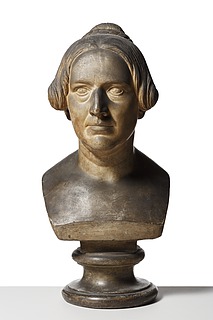

Thorvaldsen’s portrait bust of Christine Stampe, 1842, cast, plaster. 57,4 cm, A217.

The perception that Christine Stampe later dominated her relationship with Thorvaldsen is primarily due to her posthumous memoirs about the time they spent together. This was obviously also a consequence of the fact that Stampe to a large extent won the contest for Thorvaldsen’s time and favour by offering him a straightforward disposition, unlimited admiration, and a good life and tolerable working conditions at Nysø. Here he was able to relax and work, far from the constant workshop visits, dinners, and compulsory parties of the capital. The collection of works executed and left at Nysø by Thorvaldsen has also contributed to Stampe’s position as the central figure in Thorvaldsen’s final years. That this monopolization of the sculptor was not without problems can be seen in numerous accounts, among them the comments made by the baroness’ grandchild, Rigmor Stampe, in the revised edition of her grandmother’s memoirs:

[...] Each of his [Thorvaldsen’s] acquaintances considered himself to be his friend; both those he had seen in Rome and his new companions. And each of these friends thought that they had a personal claim on him. It is easy to understand their resentment when, six months later, he suddenly attached himself to one home, Nysø, and to one friend, Baroness Stampe. There was general disappointment and indignation, always expressed in the same way. Liebenberg writes that Thorvaldsen often came to their home, “before Baroness Stampe really had got a grip on him”; he often came to the home of Mrs. Hohlenberg, née Malling, “before Baroness Stampe got him in her clutches”; Mrs. Hohlenberg “did not like Baroness Stampe”, and one sees that there was constant friction among them over trifles. — And so on. So, among the people excluded there were strong feelings — not against Thorvaldsen, of course, but against Baroness Stampe [...]

The German painter and art agent Johan Bravo, who supervised Thorvaldsen’s rooms and workshops after the sculptor’s last stay in Rome 1841-42, actually declined to have anything to do with the baroness:

[...] And if he had requests or orders for me, I would gladly perform them for him, only as I asked him when he left, spare me the faultless Madam Baroness. [...]

One also senses the irony of the Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen when, in a letter to the his protector Jonas Collin, he gives a more mildly critical description of how his hostess at Nysø monopolized the sculptor:

[...] I gave him [Thorvaldsen] your letter and told him that if he needed a secretary with regard to this or any other matter, I was entirely at his service, but the Baroness interrupted me at once, saying that it was her task to be in charge of all correspondence [...] She seems to live completely for him and tells him that as long as he lives, he shall stay with her every summer and work in this studio. [...] Last night, at dinner, it was amusing to see how the Baroness and her sister, Mrs. Schou, were making a fuss over him, he was seated between them and – indeed, it was very pretty. [...]

Sarcastic tongues even referred to Christine Stampe using the name of a contemporary animal trainer, Madam Klatt, who exhibited her elephant on her own terms and for her own benefit. In the comparison with Stampe, Thorvaldsen was assigned the role of elephant as the prestigious public attraction.

In contrast, Thorvaldsen’s connection with the Puggaard family is neither as well known nor as well documented. They got to know Thorvaldsen during a six-months stay in Rome from the autumn of 1835 to the spring of 1836 and were among those who, after the sculptor’s return to Denmark, found themselves defeated by the Baroness’ near monopoly. Bolette Puggaard, in particular, seems to have developed a close relationship with Thorvaldsen during their stay in Rome, where, for some time, she received daily visits from him, danced with him, and let him dress up in her clothes. At some point, Thorvaldsen also owned two paintings with Italian themes, painted by Bolette Puggaard during her stay in Italy. Contrary to the terms of Thorvaldsen’s will, they were both removed from the collections by the board of the museum after the deaths of both Bolette Puggaard and Thorvaldsen. The curator of the museum, Ludvig Müller, did not think that they had artistic value and therefore would never be exhibited. First one and later the second painting were returned to Hans Puggaard.

After their stay in Rome, Hans Puggaard became one of the promoters and main contributors to the collection for the establishment of Thorvaldsen’s Museum. In spite of the couple’s prominent place in the museum frieze, their importance in connection with Thorvaldsen has so far been only partially examined. The family was affected both emotionally and socially by Thorvaldsen’s preference for Nysø, but their political cause also suffered from the loss of a potentially effective advocate.

|

|

Portraits of Hans and Bolette Puggaard, painted by C.A. Jensen, 1828 and 1838, respectively, oil on canvas, 23,3 × 18,5 cm and 23,5 × 18,7 cm. Aros – Aarhus Art Museum.

Some things, however, are known. In a 1978 article, the art historian Marianne Saabye describes the Puggaard family’s stay in Rome based on the diary from the journey of their 14-year-old daughter Marie Puggaard. The architectural historian Kirsten Nørregaard Pedersen’s extensive work from 2011 on Pompeian-inspired interior design in Denmark gives a detailed description of the Puggaard family’s two residences — the apartment at 62, Store Kongensgade in Copenhagen and the country house Skovgaarden in Ordrup. This publication also contains a more detailed presentation of Hans Puggaard’s political views and influence in domestic politics. It becomes clear that he and his still famous son-in-law Orla Lehmann were among the most prominent people working for the abolition of the absolute monarchy in Denmark. Cand. mag. and former member of parliament Hanne Engberg deals with the special and complicated relationship between mother, daughter, and son-in-law in the book En Kærlighedshistorie. Maria og Orla Lehmann 1843-49 from 1991, in which she draws a picture of two intellectually gifted but structurally limited women. In Saabye’s article, in particular, Bolette Puggaard is primarily presented as a delicate upper middle-class women and a chronically ill amateur painter with a somewhat exaggerated opinion of her own artistic talent. It is not until Nørregaard Pedersen’s and Engberg’s descriptions that Bolette Puggaard emerges as the woman described in H.N. Clausen’s eulogy at her early death in 1847. On that occasion Clausen, a liberal theologian and friend of both the Puggaard family and Thorvaldsen, said:

[...] There is more in this farewell than the mere thought of this loving, devoted mind. In it, there is gratitude for the best that we can leave behind at our passing: for a picture, a memory that we can rejoice in and be edified by. It is the noble memory of a woman’s soul, quiet and unostentatious, yet bold and free, sincere and true in her speech and all her dealings, warm and strong in her feelings, compassion, and commitment to all that is healthy and true and good; [...]

“Approximately the Same Relation as Mrs. Stampe”

The very close relationship of the Puggaard family with Thorvaldsen is also made clear in a confidential memorandum from the abovementioned Jonas Collin, who wrote that Hans Puggaard “has approximately the same relation to Thorvaldsen as Mrs. Stampe”. This is in agreement with Stampe’s and Puggaard’s placement in Sonne’s frieze. It should perhaps be added that Hans Puggaard, like Thorvaldsen, had grown up in a poor family in Copenhagen and had worked his way up to his present wealth and the consequent influence. He was also, like Thorvaldsen, known for having retained his modest style in clothing, for his unpretentious and straightforward manners, and for refusing to follow hierarchical rules, especially as far as the King was concerned. In this respect, each might have seen himself in the other. On the other hand, Thorvaldsen’s relationship with Bolette Puggaard was determined by mutual sympathy, by art, and by the conception of the role of art in society.

Thorvaldsen’s appreciation of the family is also seen in the fact that the sculptor only charged the price of materials and transportation of the marble relief The Graces Listening to Cupid’s Song, A601, as mentioned later in a letter dated 10.4.1844 from Hans Puggaard:

[...] he [Thorvaldsen] averred in the most friendly terms that he did not want a penny more, and that he was very pleased to know that his Graces were with a family for whom he felt so much sympathy, and where he knew that his work would be appreciated both for its own sake and for his; [...]

There is no doubt that the family, including Marie, were close to Thorvaldsen, and that their time together in Rome was free and light-hearted — it was, for example, at a party with the Puggaard family in Rome that Thorvaldsen ended up dancing around with a ham.

Background, Common Features, and Fundamental Differences

Christine Stampe and Bolette Puggaard have several features in common. They were both the centre of cultural gatherings for the artists and intellectuals of the period and are both described as women who spoke their minds without fearing the opinions or judgment of other people. Both were almost 30 years younger than Thorvaldsen; they were married to financially secure husbands; they had children. At the same time, they were relatively liberated women whose husbands evidently allowed them to pursue their ideas to an extent that was unusual for the time even though their limitations seem large today. For Stampe, this was primarily due to the baron’s eccentric personality, cf. also his biography. For Bolette Puggaard, later sources suggest that Hans Puggaard’s feelings for her were not requited, and that her marriage had not been voluntary. Partly because of that, she may have felt a strong need to influence her fate.

Hans Puggaard’s support for his wife’s preoccupation with Thorvaldsen may be seen in his present for her birthday on 7.2.1838, which was a copy of C.W. Eckersberg’s portrait of Thorvaldsen already famous at the time. She wrote enthusiastically about the present to the subject of the portrait:

[...] Needless to say, I am pleased to see you every day! It is true that you are younger in the portrait than I have ever seen you: — but I find everything that I came to know when I saw you in wonderful Rome. [...]

For her birthday in 1838, Bolette Puggaard’s husband gave her a copy of C.W. Eckersberg’s portrait of Thorvaldsen: Bertel Thorvaldsen in the robes of the San Luca Academy, 1814, oil on canvas, height 90 cm, width 74 cm. The Royal Academy of Art, Copenhagen, inv. no KS 38.

It seems safe to assume that Christine Stampe was more than usually taken with Thorvaldsen.

In order to understand the connection between the openness of the two marriages and the women’s idolization of Thorvaldsen, it is tempting to quote lines from the Canadian poet and musician Leonard Cohen’s text Famous Blue Raincoat from 1971, in which a husband, in a letter to his wife’s already cooling lover, thanks him for making her blossom:

[...] Yes, and thanks, for the trouble you took from her eyes// I thought it was there for good so I never tried [...]

Solicitude and Admiration

On a down-to-earth level, both women must have fulfilled, at any rate periodically, a desire in Thorvaldsen for loving care in familial surroundings.

In Marie Puggaard’s diary from the first stay in Rome, Thorvaldsen is quoted as regretting that he had been “camping out” for so long and never married. From this she drew her own conclusions, based on her own conventions, that it must be because “there is never anyone (he did not say that) who makes life confortable for him, and he has to go and eat with a family and never sit by the fireside, it’s really pitiful”.

As far as pampering Thorvaldsen is concerned, the Puggaard women seem to have taken the lead during their stay in Rome. That he himself contributed to starting this personality cult may be seen in the following description of the family’s first prolonged meetings with Thorvaldsen in Rome. Prior to the situation described in the quotation below, Hans and Marie Puggaard had spent the morning sightseeing in Rome and then picked up Bolette Puggaard in order to visit Thorvaldsen for the first time at his home in Via Sistina:

[...] [we] went to the delightful Thorvaldsen; he let us in himself, and he was so nice, he is much nicer and better and more beautiful than any of the portraits one sees, no one was going to feel that this was the great man who had created all those infinite delights. [...] When we had been there for some time, we left this angel of a man; [...] Today Monday we, Mother and I and Father, went to Thorvaldsen in his workshop; we entered a carriage house with paper windows, where the great man was perched on the head of a colossal horse on whose back the emperor Maximilian was sitting, which was to go to Munich, he came down to us, and when Father left, he explained and told us about all his works, [...] When we had seen this workshop, he went with us to another where they mostly worked with copies of other things [...] he himself picked some roses from his garden, which he gave to us and which will be treasured as relics.

EveryoneMother and I are almost crazy about him and his works [...]

Note that the word “everyone” at the end has been deleted and replaced by ‘Mother and I”. – Apparently Hans Puggaard was not so enthusiastic at the beginning, but then he did not get a personally guided tour and roses. However, his relation to Thorvaldsen and his art changed later — see his letter dated 10.4.1844.

Albert Küchler: Marie Lehmann, née Puggaard, as an Italian woman with a tambourine, no date. Nivågaard Collection.

After the time spent with Thorvaldsen in Rome, it is not surprising that Bolette Puggaard sent a brief but clearly wistful note after their departure from the city, signed with her first name:

[...] Bolette sends kind regards, she misses Rome and Thorwaldsen! [...]

Back in Denmark, Bolette Puggaard continued her solicitude for Thorvaldsen in a letter dated 20.2.1838, which ends with a reference to an episode during the stay in Rome. Although the details are not known precisely, it is clearly about Thorvaldsen having been too lightly dressed for the weather:

[...] You must believe that I was worried, and a little angry with you, because you stayed in Rome during the cholera — thank God that you kept well! — how is your chest? Are there sleeves in those flannel vests? I shall not forget your imprudence [...]

Baroness Stampe displays the same kind of solicitude when she writes in a worried tone to Thorvaldsen (using the familiar du-form of the personal pronoun) after she herself had been forced to leave Rome before the sculptor in 1842:

[...] let me know if you have had a bath and had your legs seen to? and if you are generally well now that you have put away the woolen vests as it must be very hot in Rome — but for God’s sake you must wear the cotton ones, they fit you? everyone says that if you wear linen shirts directly against your skin, you will very easily catch cold here where you perspire so much [...]

The Struggle for Thorvaldsen’s Presence

Several letters show that both Puggaard and Stampe felt greatly deprived when Thorvaldsen was not part of their everyday life. In the letter quoted above from Stampe to Thorvaldsen, she really badgers him to keep her informed of his doings:

[...] Holbech promised me to keep a diary of the things you did, and how you felt, I wish to God that I had someone better, remind him to write but you yourself alas are you completely cold and indifferent for God’s sake write to me, and in detail, what difference does it make to you if you spend a couple of hours in the evening writing[.] Just pretend that it is one of those visits that you always have time for; [...]

While Stampe demanded and received reports from the sculptor C.F. Holbech regarding Thorvaldsen’s Roman activities, the Puggaard family headed for Rome again, partly because of Bolette’s poor health, and partly, presumably, in the hope of seeing Thorvaldsen again and perhaps even bringing him back to Denmark. In a letter to Thorvaldsen in the summer of 1842, Marie Puggaard wrote that he should not even think of returning home before they arrived:

[...] It seemed so ghastly to me that we would not be able to be with you that I have asked everyone who was going to Rome to tell you to remain there quietly until we came for you; it would really be an nasty trick of fate if you were off to Copenhagen when we came to Rome; I do not think I could put up with it; for you are so necessary and essential to my memories of the happy Roman days that it would not be the same city if we arrived and failed to find everything as before. [...]

However, Thorvaldsen did not wait, and their paths must have crossed. Thorvaldsen returned well before the Puggaard family, and Marie Puggaard returned as Orla Lehmann’s fiancée.

Pragmatist or Revolutionary?

In spite of their similarities, the differences between Stampe and Puggaard are conspicuous — most visibly in their handwriting: Stampe wrote the Gothic letters that were the tradition of the time, Puggaard the modern Latin ones. Somehow, this is a telling image of the respective agendas in relation to Thorvaldsen and contemporary political currents. Like her husband, Bolette Puggaaard was a clear opponent of Absolutism as this article will show. As far as Stampe is concerned, she made great efforts in connection with the royal couple’s visit to Nysø; took care that Thorvaldsen contributed a relief as a present on the occasion of the couple’s silver anniversary in 1840. She lamented that he did not take part in the coronation–anointment ceremony, and that he refused to make a drawing for a joint artists’ album on the same occasion. At first sight, this seems to indicate that Thorvaldsen, following his personal political convictions, which by now have been well documented in a roundabout way, should have stuck very close to the Puggaard family and their clamorous insistence on the freedom and equality of the individual. But he did not do that.

As mentioned above, it was primarily Christine Stampe, who won the struggle for Thorvaldsen’s time, presence, and prestigious art after his return to Denmark in 1838.

In addition to her solicitude, her insistence with regard to the production of works, and the importance of her personal and straightforward friendship, Christine Stampe voluntarily assumed the role of the guardian and protector of Thorvaldsen’s reputation before and after his death. This included a form of censorship of his correspondence that can be seen in the quotation from H.C. Andersen above. We also know from her memoirs that she repeatedly advised and carried out the burning of some of his personal papers (i.e. papers that she — and probably also Thorvaldsen himself — thought it best to destroy before posterity could see them). It is not known what these papers actually contained, but it is certain that very few texts or drawings have survived that might have offended contemporary eyes. In return, at Thorvaldsen’s request, she personally burnt all the 97 letters that she had received from him. Thus, his posthumous reputation would remain largely unblemished and, in her eyes, would be more edifying to posterity.

Christine Stampe conferred on herself the role of a royalist and bourgeois keeper of Thorvaldsen’s posthumous reputation — he was to appear as the good, modest, straightforward, and loving, indeed almost childishly genial example. At the same time, however, the Baroness herself was paradoxically — and fortunately, one might add — so free of the who-do-you-think-you-are attitude and moral yoke of the time that she was able to appear if not formally, then at least semi-officially as Thorvaldsen’s partner on several occasions during the journey to Rome in 1841-1842. Conventions were less strict in Rome than at home.

The personal relationship between the Baroness and Thorvaldsen was clearly very close and quite equal, but in the view of posterity her burning of “unsuitable” papers and her insistence on Thorvaldsen being a loyal subject to the monarchy make her appear more reactionary than Bolette Puggaard.

Thorvaldsen and his Art as Political Statement

Even though Christine Stampe was born middleclass, she was apparently not anti-royalist like the majority of the liberal citizens of the time, who, in the wake of the American Declaration of Independence and the French Revolution wanted to abolish Absolutism and introduce a free constitution. To many of these, and to the Puggaard family in particular, the ideal was a new interpretation of the democracy of Ancient Greece and a repetition of the Roman republic. To the initiated eye, Thorvaldsen and his art expressed these ideals of liberty and equality and could therefore be used as a political statement.

It remains unknown whether it was Hans or Bolette Puggaard who first had the idea that Thorvaldsen should design the above-mentioned, extensive decoration of the family’s apartment and country house; they probably worked together. It is certain that the design and the unfortunately unrealized plans for a Thorvaldsen pavilion have served several purposes — as a cosy and edifying souvenir, as artistic inspiration to Bolette Puggaard’s own paintings, and, not least, as a political and cultural statement to the world.

As Nørregaard Pedersen points out, the Puggaard couple’s purchase of works by Thorvaldsen and Pompeian-inspired interior design for their apartment as well as their country house must also be seen as a clear expression of a liberal and democratic attitude. The fact that the Puggaard family also, to a large extent, had both places decorated with plaster casts and not marble works can also be seen as a sign of an intentionally democratic attitude and an insistence that art and its insights belong to everyone and not just the upper classes with their addiction to exclusive materials. As one of the richest merchants in Copenhagen at the time, Hans Puggaard might have chosen much more luxurious materials. However, he was also one of the founders of a shop that sold plaster casts of Thorvaldsen’s works in Copenhagen in connection with the collection for the establishment of the museum. This supports the hypothesis that it was a conscious act on his part: The sale of casts boomed from the 1830s and well into the 20th century, and the results can be seen to this day in porticos, gateways, staircases, and private homes all over the country. Even today, Thorvaldsen’s Museum receives commissions for plaster casts of Thorvaldsen’s works.

Constantin Hansen: Thorvaldsen’s Museum seen from Nybrogade, 1858. Oil on canvas. 36,3 × 43,8 cm, B442.

H.C. Andersen also contributed to the promotion of Thorvaldsen as a symbol of democracy and equality. In 1859 he published a story that in a different way shows the important role that Thorvaldsen, his works, and his museum in Copenhagen played as a benchmark for changes towards a more equal society. The story Children’s Prattle takes place at a children’s party in a rich merchant’s home at the end of the 1700s. Here the children compete to see whose father is the most distinguished and has the most money or power — one of these children of Blood, Money, and Intellectual Arrogance, as Andersen calls them, states triumphantly that no-one with a surname ending in “-sen” can get on in the world. A poor little kitchen boy with precisely such a “low-status” name hears this and loses courage completely. Years later, he turns out to be the one who gets the most impressive monument in the city: Thorvaldsen’s Museum. Thus, the museum stood as concrete proof that all people, irrespective of background have the right, the freedom, and indeed the duty to exercise their potential for their own and society’s benefit. This idea of the “man-of-the-people” was cultivated already in Thorvaldsen’s own time and is reflected in numerous sources, of which examples will be given below. It is in this light that Bolette Puggaard’s most valuable contribution in a Thorvaldsen context must be seen.

Bolette Puggaard’s Happening and its Context

Bolette Puggaard’s role in history was far more than that of a quiet and artistic lady. This appears most clearly in a letter from Marie Puggaard to Thorvaldsen. The letter was written on the occasion of Thorvaldsen’s absence from Copenhagen during his last stay in Rome 1841-42 — which as mentioned took place in Stampe’s company. While Thorvaldsen was in Rome with Stampe, the “topping-out” ceremony took place at Thorvaldsen’s Museum, and it was on this occasion that Bolette Puggaard expressed her political conviction and defiant courage. As described here in her daughter’s words:

[...] I hardly have to tell you that your museum acquits itself well; it looks almost grandiose, with its simple façade reflected in the canal; last winter when they were going to put the wreath on the building, Mother made a great wreath and had the audacity (in our rebellious times) to place a Tricolour at the top; the rest of us tried to discourage her with the threat of police and prosecution, which is the order of the day; but she vowed that she would defend her flag even to the King; she believed that Thorvaldsen had introduced freedom in art so that it may endure and be our foremost desire and his museum must remain free of any connection with the Palace and the like. [...]

Thus, Bolette Puggaard staged a political happening by ensuring that a republican Tricolour, i.e. the French flag, flew from the roof of the museum in protest against the monarchy whose home, Christiansborg Palace, was right next to the museum. Even though she probably did not put it there personally, one cannot help seeing her as a replica of the famous female figure in the French painter Eugène Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People from 1830.

The motivation for this clear demonstration was that the Puggaard family as inveterate opponents of absolutism had been very skeptical of placing the museum so close to the royal palace and even on a site and a foundation that had been donated by Frederik VI. In their eyes, the royal gift diminished the effect of the museum as a democratic project; as a gift from the people to an artist of the people. It was not until later, with Sonne’s frieze on the outer wall of the museum, that this democratic aspect became clear again. It is the citizens, the workers, the members of the creative class who welcome Thorvaldsen and make sure that his works are safely housed. The Royal Family is not represented in the frieze.

However, that public officials and other more conservative or just less revolutionary-minded people were tired of listening to Puggaard’s slogans is evident in a letter sent to Thiele from Rome. In this, the above-mentioned German painter Johan Bravo writes:

[...] Among famous compatriots present here are Mr. Puggaard and Orla Lehmann, and I am pleased to be able to say that the sound common sense of our artists makes fun of these gentlemen’s revolutionary declarations. Here we are, thank God, strangers to politics, and also the Holstein-Schleswig Question makes no impression or disturbance among our fellow-countrymen. [...]

Jonas Collin probably shared this view of Hans Puggaard and Orla Lehmenn. According to a letter from Hans Puggaard to Thorvaldsen, the topping-out ceremony was far quieter than desired:

[...] On this happy occasion, [H.N.] Clausen and I had arranged a little ceremony which was to have consisted in the members of the Committee — your friends and admirers had been assembled when the wreath was hoisted — a song suitable for the festive occasion was to be sung by the Academic Society etc., but Collin did not support that — thus we have celebrated the day quietly among ourselves: the Danish artists who have been in Rome had dinner with us together with Clausen and a few others — we toasted you and your museum in champagne and rejoiced that we shall soon see you among us. [...]

It is possible that Collin’s modest celebration has provoked Bolette Puggaard’s insistence that the fundamental idea behind the museum should be shown — in spite of warnings of reprisals.

In the same letter, Hans Puggaard wrote that he had seen to it that the workers who built the museum also shared in the festivities, which Collin obviously had not wanted or thought about. This reflects Puggaard’s view that everyone should be treated in the same way regardless of social class or occupation, and it seemed natural that he wrote about it to Thorvaldsen since he assumed that the sculptor shared his view. For unknown reasons, Hans Puggaard did not mention his wife’s Tricolour on the roof. From Collin’s point of view and with Bravo’s above-mentioned letter in mind, it seems logical that the royal official was uneasy about a celebration supervised by an anti-royalist family.

Unfortunately, we do not know Thorvaldsen’s answer to Hans’ or Marie Puggaard’s letters, nor can we be sure that he sent any answer at all. However, we do know that as early as 1839 the sculptor, perhaps at Collin’s request, had a letter written to the Committee for the Establishment of Thorvaldsen’s Museum. He stated that he was pleased to accept Frederik VI’s offer of a conversion of the royal coach house, and that this was not a time for disturbances and disagreements:

[...] I certainly appreciate the eagerness and good intent that inspire some of my patrons when they want premises other than the ones with which I am fully satisfied, but it would be painful for me if this would give rise to the slightest remark to His Majesty and the public authorities with the intention of changing that royal decision. My wish for my art collection is close to being fulfilled. Through this royal gift, the foundations have now been laid. The construction cannot be far behind. Through the generous and considerable contributions already made by my fellow citizens and compatriots and through the grant that is to be expected from the authorities of this city who have already shown me unmistakable proof of their affection. My age, my art, and my health demand peace and quiet, and no one who is fond of me will disturb these things that are so important to me. [...]

It is therefore possible that Thorvaldsen also believed that Bolette Puggaard’s political activism would interfere with the advancement of the museum project although one may assume that it warmed his republican heart. Thorvaldsen’s acceptance of Frederik VI’s gift may also be due to the fact he was considerably more sympathetic to this King than to his successor Christian VIII. As Crown Prince, the latter had earlier been forced to borrow a considerable fortune from the sculptor in order to pay for his private extravagance. Against the background of such financial and political power games, a royal gift could be accepted with equanimity or even silent triumph.

In her memoirs, Johanne Louise Heiberg wrote about the difference in Thorvaldsen’s relationships with the two kings:

[...] He spoke about Frederik VI with great affection and devotion. “He was no expert on art,” Thorvaldsen said, “but then he did not pretend to be.” And then he switched from Frederik VI to Christian VIII and spoke with such intense bitterness that he became quite eloquent. “He wanted to be a patron of the arts and sciences,” he exclaimed, “And what did he do for them? My poor pictures that I gave to my country are still in their crates because they could not get a roof over their head until one penny after another had been laboriously begged although I had contributed a not inconsiderable sum for this, too. He can boast of me and my works abroad, that he can, that he will while at the same time both I and they are unimportant to him. And then he thinks that one should feel amply rewarded when he invites one to his boring Royal banquets, where one obviously comes only to grace his table.” His noble figure became almost larger during these statements; his usually calm, beautiful, blue eyes blazed with fire. “It sometimes amuses me,” he said, smiling mischievously, “to displease him; thus recently in Roskilde. Ørsted and some other friends of mine, who were at the Provincial Consultative Chamber, had invited me to come so that we could have a jolly dinner together. As I was walking along Roskilde Road, the King came along; he had the carriage stop and hailed me: “Have dinner with me, Thorvaldsen,” he then said. “I cannot do that, Your Majesty, I am dining with some good friends.” — “Well, then I must give way,” the King answered bitterly and ordered his coachman to drive on. I had heard others mention this little incident that Thorvaldsen told me here as proof of his great naivety; it had not occurred to anyone that it was a proud artist asserting his personality in the face of a sovereign king. [...] “At the coronation ceremony”, he continued, “I was expected to be present. I refused. Was I now, like a fool, going to get and wear the robes of a knight; no, I did not want to do that.” [...]

Bolette Puggaard, on her part, was eager to demonstrate ideas of liberty and equality and to use the museum project and Thorvaldsen as its prominent leader. This should not only be seen in the light of Hans Puggaard’s political efforts, but also in the fact that the absolutist tribunal had sentenced her own brother, the journalist Johannes Hage, to both a fine and lifelong censorship, a blow which had played an important role in his suicide in the autumn of 1837. Her later son-in-law Orla Lehmann had been sentenced to a term of imprisonment after a speech that was judged to be too liberal.

Not everyone in Denmark was as “lucky” as Thorvaldsen to have been able to live a life of relative freedom in Rome, far from the constricting rules of the state, or like Johan Bravo to gloat and laugh at Hans Puggaard’s and Orla Lehmann’s slogans and at domestic politics in Denmark.

Bolette Puggaard’s eagerness to have Marie married to Orla Lehmann, as described in Engberg, op. cit., may also have been influenced by the fact that many people regarded Orla Lehmann as Hage’s journalistic heir. According to Lehmann himself, he saw Marie for the first time at Hage’s funeral — and fell in love. The link between the dead brother and the ambitious liberal Lehmann must have been strong — not least for Bolette.

There is even a poem that links Johannes Hage’s funeral and his work for freedom of speech and democracy in Denmark to Thorvaldsen’s return to Denmark, his popularity, and his museum. According to the poem, the journalist’s and the sculptor’s efforts together with the coming Provincial Consultative Chambers created a new hope for greater justice in the country. The democratic seeds that Hage sowed could finally sprout and flower through Thorvaldsen’s return and the building of the museum if people worked together and helped each other. The point of the poem corresponds fairly accurately to what Hage himself had said in defence of the museum a few months before his suicide. Here, he made a similar comparison between the process of collecting money for the construction of the museum and what people otherwise would be able to achieve by combining their efforts and working together — in other words, an ill-concealed reference to politics:

[...] It will show us what can be achieved by combining our forces, it will give us the courage and the desire to combine our forces for the achievement of other great and beneficial purposes; it will arouse and feed the conviction that even though our forces are small, we can still do much if only we dare believe in the possibility. [...]

This striking link between Thorvaldsen and local Realpolitik which Bolette Puggaard’s happening illustrates can also be seen in numerous items in the contemporary press. A controversy in the press at the end of April 1837 provides an example of this. The anonymous writer, who signs himself “A Friend of Art and Our Country” and invites support for the future Thorvaldsen’s Museum, might well belong to the group surrounding Hage, Lehmann, and Puggaard as his opponent describes him as “a dangerous and cunning member of the Opposition who knows how to exploit improperly the freedom of speech given by the King and emphasized by himself.” Perhaps, the opponent writes, it may be a woman? It has not been proved that Bolette Puggaard had anything printed in the newspaper, but her letters and the Thorvaldsen happening certainly show that she was an able writer and an eager champion of democracy.

In a book review in Berlingske Tidende one could read how Thorvaldsen and his art could be directly linked to the democratic rule of progressive princes:

[...] In him [i.e. Thorvaldsen] we find the same unpretentiousness and modesty as in H.C. Ørsted. He does not attribute great merit to his work and always wishes to make it better. If everyone had that spirit of mildness and meekness which must be aroused by contemplating his works, by reading about him and thinking about him, then the freedom of speech and of the press would soon be common, even in the most despotic states; and the word would be loved by the princes just as we read here that this man of the people was loved, especially if the language were structured as beautifully as his works. One must admire the beautiful way in which King Louis honoured him, so to speak, in his workshop, and the friendly relationship between the King and the artist. The same spirit that induced the Prince and his Bavarians to take an interest in Thorvaldsen also moves them to build railways and to connect the Danube and the Rhine by a canal. It is also worth noticing how he is eliminating the prejudices of the Catholics and preparing a reconciliation among church parties by honouring Pope Pius VII’s memory with his art. [...]

According to this view, Thorvaldsen builds bridges, destroys cultural and social distinctions, and is an inspiring example through his personal modesty and through his art, which embodies the best and the most fundamental things in life. There are actually no limits to his influence, for Thorvaldsen and his art not only realize the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity, but this way of thinking also indirectly leads reasonable rulers actively to improve the world through concrete undertakings such as railways and canals.

The attempt to use Thorvaldsen and his work to embrace and educate the whole population is repeated in an article that pedagogically explains to the rural population why Thorvaldsen and his museum are of such current importance — even if they have never heard about the man or seen any of his works:

[...] I must first of all ask you, my dear reader, whom I like thinking of as belonging among ordinary country people, not to expect me to make it quite clear to you, how great a man Thorvaldsen is, and how important he is to all of mankind. When I say that the marble images that he carves spread more natural truth and more divine wisdom across the whole wide world than a hundred priests and professors are generally capable of, then you will not understand what I mean; partly because I cannot show you his images, partly because, if you saw them, you would not feel that you became wiser or better for it. Even in living human beings we are not always able to infer the internal from the external: we cannot, from a person’s airs, gestures, and posture, tell what goes on in his soul, what he thinks and feels now. And it must be even more difficult for you who have no training in this to understand what the sculptor intended with his marble figures. However, many people understand these images’ silent language, and they maintain that the more they contemplate them quietly and attentively, the more they feel that it is as if thereby higher and brighter thoughts, nobler and stronger feelings are born within them than they have known before. [...] At this moment I only want to point out that since you are compelled to believe that Thorvaldsen must be a most excellent and unusual person because both kings and emperors associate with him as their equal, and the wisest and noblest in all of Europe treat him as their beloved lord and master, then I expect that you might want to hear about his life. [...]

The attempt might bring to mind the American quartet from the 1930s and 40s The Ink Spots and their song I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire. Here the lead singer Bill Kenny first sings beautifully and correctly, but later he speaks the same text in popular, everyday language over the melody. The point seems to be that even the things that at first seem to be cultured, nice, and even impersonally elitist are in their essence for everybody — what matters is the public’s attitude and the form of presentation or communication. As is well known, the attempt to destroy the distinction between elitist and popular is repeated in the modernism and post-modernism of the twentieth century, where art again has to be for everyone and not just for the museum visitors of the middle and upper classes and rich art collectors. Whether this really succeeded is another matter.

A painting showing the ideal influence of Thorvaldsen’s Museum as a place for the education of common people. Carl Dahl: A.F. Tscherning Showing Two Farmers Around in Thorvaldsen’s Museum. Bought at auction 1977. Provenance: Johan Hansen; Katy Brunow. B451.

Another newspaper quotation regarding the establishment of the museum is even clearer and more bombastic when it emphasizes the contrast between the museum as a popular memorial to a free man’s work and the self-glorification of kings and noblemen in the form of equestrian statues and the like:

[...] It [the museum] is different from these leaden horses which earthly vanity erected to itself, from these marble sarcophagi in which earthly vanity buried itself; indeed, it is different from that proud Vendome column “ex ære capto”, which “no mother can see without tears.” — “No peasants have been distrained to please any prince and to adorn his squares and gardens,” — this is the free work of free men! Therefore, it is not just a memorial to Thorvaldsen’s work and an adornment for Denmark, — it is also a memorial to the civic spirit born of the longing for freedom, to the national sentiment aroused by culture in Denmark. [...]

The author of the article was Orla Lehmann. Also H.N. Clausen, who was a friend of the Puggaard family and delivered a eulogy on the death of both Thorvaldsen and Bolette Puggaard, wrote several articles in defence of the museum arguing that the man and his museum would be instrumental in creating a better Denmark.

Summary – the Ethical Genius and the Reckless Revolutionary

Both Just Mathias Thiele, mentioned above, and Christine Stampe claimed that they had been chosen by Thorvaldsen to write his biography. In spite of the competition between them and the basic differences in their works about Thorvaldsen, they both still left posterity with a picture of the sculptor that is closer to that of their rival than, for instance, to the actress Johanne Louise Heiberg’s or to H.C. Andersen’s more rebellious picture of Thorvaldsen.

Christine Stampe tried to influence the picture of Thorvaldsen of her own and later ages by censoring his papers, inviting him to stay on good terms with the royal family — including the less appreciated Christian VIII — while at the same time insisting on his right to live freely. She made sure that the aging sculptor could work in peace and in familiar surroundings. Politely put, one could say that she supported the pragmatic and gently accommodating side of Thorvaldsen and emphasized his genial, creative, playful, and straightforward nature. In that way, her influence paradoxically came close to that of her nearest rival, Thiele, who in his biographies of the sculptor similarly polished Thorvaldsen’s life so that it appeared more respectable and correct in relation to contemporary norms. In her memoirs, Stampe stressed Thorvaldsen’s bluffness and stubbornness more than Thiele did but still in such a way that it seems ethically “correct” and thus never becomes strictly speaking political but rather ethical or exclusively linked to the development of the museum project. Generally, her memoirs support the image of Thorvaldsen as a “decent” human being — and that she and Thorvaldsen were a good match. One might say that she promotes the image of Thorvaldsen as the ideal man of the golden age but without the clear distancing from the monarchy which, according to e.g. Ragni Linnet, op. cit., was an implicit part of the contemporary cultivation of the intimate and the familiar:

[...] Woven into the description of everyday life are civic virtues like trustworthiness and virtuousness [...] industry and honesty [...] naturalness, unaffectedness and sincere love [...] and finally family solidarity. [...]

All these images have one thing in common: They are unpretentious, unaffected images of everyday life. Even the fact that the metaphors must be “true to life” can be seen as a reaction to the feudal hierarchy with its prioritizing of external forms and as a confirmation of the importance that the middle classes attach to intrinsic values and the individual. In the self-knowledge of the middle classes, man is nothing by virtue of outward rank, birth, etc. but by virtue of his own actions and abilities. As opposed to Absolutism — there is nothing to hide behind façades and no need of elaborate set pieces.

Bolette Puggaard and her family supported the same virtues but also tried to a large extent to present Thorvaldsen as a revolutionary leader and thus emphasize the underlying political values. They probably came close to exploiting his status as a popular and self-made man of the people in their struggle for a free constitution in Denmark. Although they were far from alone in using him as a standard-bearer, Bolette Puggaard’s clear and confrontational protest against Absolutism in connection with the topping-out ceremony at the museum was probably the most striking example of this way of looking at Thorvaldsen and using him. The Puggaard family might well have preferred Thorvaldsen to distance himself more clearly from the monarchy — not just through his discreet and informed expressions in art and in style but by openly refusing the King’s offer of site and foundation for the museum so that it could remain a purely democratic project.

There is no doubt that Thorvaldsen sympathized with the views of the Puggaard family and distanced himself from Stampe’s correct behaviour regarding the monarchy, or at any rate Christian VIII, but after his return to Denmark he seems to have considered the museum project more important than a clear and official position on the political struggle in Denmark. As witnessed by Heiberg’s quotation, he continued discreetly to excuse himself or to avoid royal obligations, and he volunteered as a figurehead in several circles and at arrangements of a politically liberal nature, but he was not to be found on the barricades as Puggaard and Lehmann were.

For a long time, however, this seems to have been his tactic for dealing with power structures — choosing his own way and making and following his own priorities by gently steering free under a layer of irony or hesitance, and showing through his actions that he valued democratic and humanistic ideas highly. All this was much easier for him as an independent artist in Rome — far from the power of the state in Denmark, and it is far from certain that even this discreet rebellion would have passed unheeded if he had stayed in Denmark or returned before he had become a much-admired celebrity. In Rome he was able to insist on being a free man and a free artist without being subjected to Danish censorship or even harsher sentences like Orla Lehmann or Johannes Hage.

H.C Andersen quoted the sculptor as saying, on a warm Christmas Eve in Rome in 1833, that his long absence from Denmark was due to the cold weather:

[...] The weather was lovely, like a summer’s night in the North. “It is different from home,” Thorvaldsen said. “ The cloak becomes much too heavy for me”. [...]

The heavy cloak — not only literally made of heavy wool because of the wind, the rain, and the cold, but metaphorically woven of censorship, middle-class values, and a pervasive monarchy — Thorvaldsen was able to shed all this in Rome and don the liberty cap.

Thorvaldsen’s relief The Genie of Peace and Freedom, A529, from the last year of his life. According to his valet, C.F. Wilkens’ memoirs , Thorvaldsen changed the subject and the title at the last moment by adding Phrygian caps, the antique slightly long, baggy caps, also known from the French Revolution as Jacobin caps or simply: the liberty cap. In the press, the relief was interpreted as honouring the monarchy — something that made the sculptor react promptly.

References

- Hanne Engberg: En kærlighedshistorie. Maria og Orla Lehmann 1843-49, København 1991.

- Kira Kofoed: Thorvaldsen på Skovgaard, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk 2018.

- Erik Mortensen: “Thorvalds Museum. Den kulturpolitiske, sociale og politiske kontekst, herunder også om modtagelsen i pressen”, in: Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum, 1998, p. 169-175.

- Kirsten Nørregaard Pedersen: Pompejanske rumudsmykninger i 1800-tallets Danmark, [Humlebæk] 2011, bd. I, p. 106-148 og 149-164.

- H. Lehmann: Hans Puggaard. Et Hundredaars Mindeskrift, København 1888.

- Ragni Linnet: ‘Guldalderens billedudtryk i filosofisk optik’, in: Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum, 1994, p. 21-35.

- Rigmor Stampe (ed.): Baronesse Stampes Erindringer om Thorvaldsen, København 1912.

- Marianne Saabye: ‘Puggaardske studier’, in: Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum 1978, p. 72-115.

- Carl Frederik Wilckens: Træk af Thorvaldsens Konstner- og omgangsliv, samlede til Familielæsning, København 1874.

Works referred to

Last updated 09.04.2021