This is a re-publication of the article originally published (in Italian) in connection with the exhibition: ‘Joseph Anton Koch nel 250° anniversario della nascita’, held at Museo Civico d’Arte Moderna i Olevano Romano, Italy, from the 27.th of July until 4.th of April 2018, cf. Pier Andrea De Rosa, op. cit.

This article stands on many legs, some of which may well be a bit mismatched. It is to be read, first and foremost, as a sketch—an opening—of a field that is as yet relatively unexplored. To provide general background, a number of the well-known basics are summarized about the ties of friendship and collegiality between the German painter Joseph Anton Koch and the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, some two years younger. After briefly illustrating the two artists’ collaborations and mutual inspiration, a study is undertaken of the more fundamental commonalities in Thorvaldsen’s and Koch’s approaches to sculpture and landscape painting, respectively. The present article by no means exhausts these explorations; rather, the hope is to highlight a number of perspectives that can open up new paths in both Koch and Thorvaldsen research.

|

|

| Eberhard Wächter: Portrait of the painter Joseph Anton Koch, 1795-1798. Oil on canvas. 29,4×22,9 cm. B165. | Thorvaldsen’s Self Portrait, 1794. C885. |

From 1817 to 1819, the German author Henriette Herz was living in Rome. In her memoirs from the period, she described Joseph Anton Koch and the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen as the two people among all the artists in Rome that one would most have liked to have conversed with, but with whom one unfortunately could not speak with except with difficulty, or at risk of harm to one’s mental and linguistic virtue. The reason why Herz held these two artists in such high esteem was due to their so-called “originality” or “original essence” [Ursprünglichkeit] and their unspoiled inner health:

In most of these young artists there was a certain sickliness, despite the otherwise highly amiable personalities that very many of them had. Only two of the artists then living in Rome actually gave the impression of an original essence [Ursprünglichkeit] and unspoiled inner health, but these two were among the older artists. These were Koch und Thorwaldsen—the latter, though, was no German, but often associated with the German artists—both of whom clearly unseated the dominant “pious” line in their artistic fields: the former as a landscape painter, and the latter as a sculptor. However, it was not possible to speak very much with either of them; especially not for a woman, in the case of Koch. That creator of so many beautiful and brilliant landscapes, attesting to a deeply penetrating observation of nature and an ingenious liveliness in conversation, is a Tyrolean farmboy, used to calling all things, whatever they might be, by their most obvious and earthy names, albeit often by the most descriptive and characteristic names. As for Thorwaldsen, one cannot speak with him because he actually speaks no language at all, for he has nearly forgotten his mother tongue, and still has not learned any other language well enough to express himself fluently. I often contemplated the great artist’s splendid head, his wonderfully shining blue eyes, and thought: how elegantly would such a man speak, if only he could speak at all!—But what he was able to articulate did attest to health and proficiencyI.

Herz’s perception of Koch and Thorvaldsen as a blustering farmboy and an inarticulate genius, respectively, is echoed in other, later accounts of the two artistsII ; but her words equally reflect, at root, their fundamental ideals of freedom and equality, their insistence on unpretentiousness, and their aversion to the strictly hierarchical social norms of the past. The two colleagues and friends undoubtedly agreed that it is the right of every human being to be free, to be oneself, and to realize one’s own potentials—and that art is an important pedagogical and visionary tool in the necessary process of liberating humanity.

It follows that art should itself be free and independent of the tastes of clients, critics, and patrons; and accordingly, it was of great importance to both Koch and Thorvaldsen to preserve their personal and artistic freedom far from the tentacles of and obligations due to the absolute monarchs and academies of their homelands.

Yet put bluntly, Thorvaldsen was an obedient sheep compared to Koch, who was two years older: their ideals may have been the same, but their respective approaches and degrees of success during their own lifetimes differed widely. Koch rebelled openly, and was direct in his criticism of the art academies’ organization, the modus operandi of art criticism, and what he considered his homeland’s wretched taste in art, among other thingsIII. Because of his activism, Koch had to leave the Hohe Karlsschule art academy in Stuttgart before completing his education there; was close to being arrested by the French occupation forces in Rome, on account of his political viewsIV ; and despite his great talent, early patronage, and the support and admiration of numerous colleagues, he remained throughout his lifetime more of an “artist’s artist” than a “client’s artist”—and thereby also a poor artist.

Thorvaldsen, for his part, was no less liberal-minded. But he was much more indirect in his criticism of authorities and the existing social order; you might call him a quiet revolutionary. With one single newly discovered exception, Thorvaldsen did not publish, as Koch did, critical or theoretical writingsV ; today, it is only possible to detect his having taken political stances by carefully scrutinizing his private letters or the secondary accounts of others. But beyond this, the sculptor’s silent stubbornness, and his clear insistence on his own free choice and on small-scale, discreet “happenings”VI with a political touch, makes it possible to determine his political stance beyond all doubt from his actions as well. As it happened, Thorvaldsen actually came close to realizing his political objectives. What is more, he ended up being extremely well-off financially, with the power and influence that wealth often bringsVII.

The Danish-German draftsman and painter Asmus Jacob Carstens was undoubtedly a source of inspiration to both Koch and Thorvaldsen with his distinctive and groundbreaking activism in the service of freedom. In 1781, for example, Carsten refused receipt of a silver medal for his final examination work at the Royal Academy of Arts in Copenhagen, and was expelled from the program after a public dispute in the newspapersVIII. Later, he broke in legendary fashion with the Berlin Academy in Fine Arts, with a letter—already famous in his lifetime—written in Rome at Caffé Greco on February 20, 1796, explaining why he did not wish to return home to a post as professor at the Prussian academy:

… What is more, I must … say that I do not belong to the Berlin Academy, but to humanity, which has the right to demand of me the highest possible formation of my abilities; and I never intended, and have never promised, to bind myself in lifelong service to an academy in exchange for a stipend given to me for a few years of developing my talent. It is only here [in Rome] that I can educate myself, among the best artworks that there are in the worldIX. …

Rome, in short, was the place where one could and should gain an education—as a free artist for the benefit of all humanity. The city’s collections, ruins, and history, its cafes and picturesque surroundings, became a political and artistic place of refugeX and sine qua non for Carstens, Koch, Thorvaldsen, and many others, as well as a place where artists, for better or for worse, had no choice but to stand on their own two feetXI.

Carstens arrived in Rome in 1792, Koch in 1795, and Thorvaldsen in 1797. A few years later, from 1800 to 1803, Koch and Thorvaldsen lived together at Via Sistina 141, close to Piazza BarberiniXII. Here they shared not only an interest in art and politics, but also an interest in women. As the catalogueXIII for the first large Koch exhibition in Stuttgart, in 1989, archly puts the matter, the two friends lived together and had “parallel love affairs.” The guesthouse where they lived was lovingly run by the Italian landlady and hostess Orsola Polverini Narlinghi, several versions of whose portrait are preserved at Thorvaldsens MuseumXIV.

J.L. Lund: Portrait of Orsola Polverini Narlinghi, Thorvaldsen’s landlady in Rome, 1800-1804. B448.

Bertel Thorvaldsen: Portrait of Joseph Anton Koch (?). Cupid and Psyche, C70r. S.a. Pencil, pen and ink on paper. 190×134 mm. Probably the drawings were made in the early years of the 19.th century and thus the combination of motives illustrates perfectly the life of Koch and Thorvaldsen at the time as described by Christian von Holst, op. cit., p. 11.

In the so-called Roman republic of arts, behavior and tone had been free, wild, and informal, as is attested in many accounts. In particular, the Roman cafes, including the aformentioned Caffé Greco, and the Ponte Molle artists’ societyXV gave rise to numerous ironic-political festivities. Following the German painter Friedrich Nerlys arrival in Rome in 1828, the Ponte Molle Society was organized as a wholly ironic parody of what the artists regarded as the obsolete and unfree social hierarchies and norms that held sway in the world outside the artists’ republic. Through the same society, excursions to the surroundings of Rome acquired an important role, as in the spring festivities held annually at the Cervaro grottoes northeast of Rome, of which Koch and his friend and colleague Johann Christian Reinhart, the German painter, were said to be the “Germanic rediscoverers” in around the years 1809 to 1812XVI.

Joseph Anton Koch: The Roman Campagne with the Caves at Cervaro, s.a. Pen and ink on paper. 170×235 mm., D751.

Over time, as has already been mentioned, Thorvaldsen became a very wealthy man, almost at the same rate as Koch became poorer and sicker. There are numerous letters that can still be found in Thorvaldsen’s archive in which men and women ask him for his help and support—often economically. Yet from Koch, despite their vastly different economic situations, we find no such petitions to Thorvaldsen; yet Thorvaldsen supported him anyway, presumably unprompted, by commissioning works from him—both original artworks and copies of works by other artists, including Carstens, as will be discussed later.

There was nevertheless one thing, probably a result of their economic inequality, that seems to have caused tensions between them—at least in regard to Koch’s wife Cassandra, née Ranaldi. From her one letter to Thorvaldsen is preserved, dated December 29, 1825XVII. Its contents include sharp criticism of Thorvaldsen’s treatment of J. A. Koch. Thorvaldsen had reportedly asked his friend to make a list of the paintings and drawings that he had made for Thorvaldsen, along with a list of the amounts he had been paidXVIII. Cassandra was profoundly upset by the lack of trust in Koch that she believed underlay this request for documentation; and in her letter she claims that, had Koch sold the same works to others, he would have gotten a higher price. In his wife’s view, then, it was more that Koch had done Thorvaldsen a favor than vice versa. The question of price was presumably a vexing one for both Koch and Thorvaldsen. Koch needed the income, while Thorvaldsen, for his part, needed to find a balance between being reasonable—without hurting Koch’s expectation or pride—while at the same time acknowledging that even his friends saw him as so well-off that he could afford to pay whatever he wanted.

Thorvaldsen had a number of works by Koch hanging in his home in Casa Buti, including, in his bedroom, Koch’s drawings following Carstens—a placement that, according to contemporary sources, seemed to be reserved for the works that the sculptor valued most highly:

The most beautiful of these pieces are in his bedroom. There are two motifs taken from Dante, and treated, I believe, by Koch, that seem to have earned his preference: we see there the dark and naïve side of the German imagination grafted onto the sensual melancholy of the Italian.XIX

At the same time, we know of a number of examples where artists borrowed their works back from Thorvaldsen when potential buyers were surfacing in their own ateliers. This includes Koch, who in 1822 asked Thorvaldsen to lend him the painting Heroic Landscape with Ruth and Boaz, B158, which Koch had painted, in part together with the German painter Christian Gottlieb Schick, in 1803–1804. Koch wished to be able to have it in his own atelier when the numerous English tourists were nearby; his hope was that commissions of new works or replicasXX of existing works would stream inXXI.

Joseph Anton Koch and Christian Gottlieb Schick: Heroic landscape with Ruth and Boas, 1803-1804. Oil on canvas. 87,6×116,4 cm, B158.

There can be no doubt that artists were generally pleased to have their works hanging in Thorvaldsen’s apartment, which functioned as one of the few publicly accessible collections of contemporary art in the Rome of the day. In 1828XXII, for example, the Italian painter Giambattista Bassi asked Thorvaldsen whether he could borrow back one of his paintings briefly from “cosi buono allogio [such good lodgings],” i.e., Thorvaldsen’s apartment. This formulation underscores the importance of Thorvaldsen’s collection of paintings for both artists and collectors in his day: to get one of one’s artworks included in his collection was not merely satisfying because this marked the sculptor’s approval, but also because such prominent placement contributed to obtaining future commissions for the individual artist. To have an artwork hanging there, a spot to which many travelers, art collectors, and potential patrons made their way, represented a seal of approval, and potentially an excellent advertising boost, for the individual artist. With this in view, selling one’s work a bit more cheaply to Thorvaldsen was probably a wise business decision.

Both Koch and Thorvaldsen belonged to the circle around Carstens until his early death in Koch’s arms in 1798XXIII. They admired not only Carstens’ liberal activism, but also his art; and after his death, both attempted to make their own mark on his artistic universe by realizing numerous copies of and drawings inspired by his Nachlass. As late as in 1811—and again in 1823—Thorvaldsen commissioned various drawings from Koch to be based on Carstens’ works, and the resulting mix of original works and copies in Thorvaldsen’s collections has subsequently made for its own matter of investigation in the attempt to decipher who made whatXXIV. When in 1827, Thorvaldsen considered purchasing Palazzo Giraud-Torlonia on Via della Conciliazione in Rome for himself and his collections, his intention was to have the interior of the palace be decorated following Carstens’ drawingsXXV. It is most likely that Thorvaldsen had Koch in mind as the artist responsible for this decoration work, inasmuch as Koch was involved in a similar project during the same period at Casino Massimo in Rome, for which he realized a number of frescoes with motifs from Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Collaboration and mutual inspiration among artists was generally prevalent at the time. We knowXXVI, for example, that both Koch and Thorvaldsen painted decorative figures for and on landscapes by the English painter George Augustus Wallis’, and that Koch had the Norwegian landscape painter J.C. Dahl paint decorative figures and a foreground, at the very least, for his grand painting Lauterbrunnertal near Unterseen with a view of the Jungfrau, c. 1821, B128. It has even been suggested that Dahl painted the entire picture after a drawing by KochXXVII. We also know that Koch drew the background for at least one of Thorvaldsen’s picturesque drawingsXXVIII, while Thorvaldsen, for his part, appears to have drawn figures for use by Koch in his landscapesXXIX. At times, then, there were points when it seemed anything was possible, and the artists made fruitful use of one another’s talents.

J.A. Koch: Lauterbrunnertal near Unterseen with a view of the Jungfrau, c. 1821. Oil on canvas. 74,5×98,1 cm., B128.

Thorvaldsen og Koch: Mary with Jesus og John 1801-1810. Black chalk on paper. 56,2×41,6 cm. Nysøsamlingen, Nysø129.

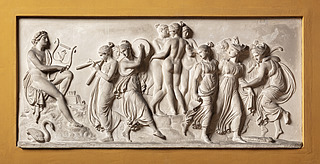

There are further works by Thorvaldsen and Koch that very likely were also realized with mutual inspiration—and often, as mentioned, with a basis in Asmus Jacob Carstens’ NachlassXXX. All three, for example, were occupied with the lyre-playing god Apollo as a motif. It is certain that both Koch and Thorvaldsen were familiar with Carstens’ drawing The Dance of the Muses on Helicon, D815, in which Apollo appears, and which remains in Thorvaldsen’s collections. It is quite probable that Thorvaldsen was thinking of precisely this drawing when, in 1804, he realized his first reliefXXXI with the same motif, as is indicated by the fact that, as on Carstens’ drawing, only eight of the Muses appear, and not all nine. It is only in Thorvaldsen’s later version, A341, that all nine Muses are portrayed—on account of which, incidentally, the sculptor has been accused of having been ignorant of the correct number of Muses when making the first version. More plausible, however, is that Thorvaldsen was strongly inspired by Carstens’ composition. And no one would dare to accuse the extremely learned Carstens of being uninformed about any aspect of antiquity or its myths.

For his part, J. A. Koch was clearly familiar with both Carstens’ drawing and Thorvaldsen’s two relief versions of The Dance of the Muses on Helicon when painting his own Apollo among the Thessalian ShepherdsXXXII. Koch’s painting seems especially to reproduce the positions of Apollo’s hand and leg in Thorvaldsen’s second relief, from 1816. Thorvaldsen bought a replica, B125, of this painting, and may have used Koch’s portrayal of the group surrounding Apollo as inspiration a few years later, when he made his own relief Apollo and the Shepherds, A344.

Asmus Jacob Carstens: The Dance of the Muses on Helicon, c. 1793. Carbonpencil and pencil on brownish paper. 481×697 mm. D815.

Bertel Thorvaldsen: The Dance of the Muses on Helicon, 1806. Not finished Marble. 73×160 cm. A705.

Bertel Thorvaldsen: The Dance of the Muses on Helicon, 1816. Plaster. 73,5×160,0 cm. A341.

Joseph Anton Koch: Apollo among the Thessalian shepherds, 1834-1835 B125. Replic of Koch’s painting in Neue Pinakothek Munich, inv. no. L.1834.

Bertel Thorvaldsen: Apollo and the Shepherds, 1837. Plaster. 30×177 cm. A344.

The mythological figure HylasXXXIII is one that occupied both Koch and Thorvaldsen repeatedly. Unusually for Thorvaldsen, the Hylas motif led him to embellish his three-dimensional artwork with landscape decorations—along with elements that seem to have been borrowed quite directly from Koch. In Thorvaldsen’s Hylas relief, for example, but not in his other reliefs, we find prominently displayed the completely or partly broken tree trunks that are so often seen in Koch’s paintingsXXXIV. In Koch’s works, the broken tree trunks help to underscore a sense of wildness or primitivity; often new buds appear in the trunks despite their having been cut or broken off previously. This makes it plausible to see the broken trunks as paralleling the ancient ruins in Koch’s surroundings, ruins whose historical and ethical essence sufficed to allow the philosophy, aesthetics, and social ideals of his own day shoot forth from the same life-giving ancient root.

In Thorvaldsen’s Alexander friezeXXXV, A503, in his small relief with Apollo and Daphne, A478, and in a few other cases, we also see something reminiscent of a background landscape; but otherwise it is remarkable how “pure” Thorvaldsen’s backgrounds are. As a rule, only the immediate ground on which the figures are walking is displayed—as, for example, the cliffs in the reliefs mentioned above, The Dance of the Muses on Helicon. By contrast, in Thorvaldsen’s two different reliefs portraying Hylas and the Water NymphsXXXVI, from 1831 and 1833, respectively, the landscape is comparatively quite prominent. The same holds for a drawing, C381, with the same motif, from approximately 1807–1809, one which is rather uncharacteristic for Thorvaldsen. That Thorvaldsen has one of the nymphs insistently stroke Hylas’s cheek—a gesture that Thorvaldsen variously incorporated into both reliefs—may well have been Koch’s inventionXXXVII.

We do know that Thorvaldsen was familiar with Carstens’ drawings of the Argonauts’ expedition, of which the myth of Hylas is a part, and that he was aware of Koch’s work on a painting with the same motif. In 1833, Koch wrote a letter to Thorvaldsen asking whether the latter still wanted “my picture depicting Hylas,” or whether he would perhaps be satisfied with another version of the motif, in which case Koch would sell the existing painting to a visitorXXXVIII. Unfortunately, we do not know Thorvaldsen’s answer, nor can we determine with certainty what picture Koch referred to. Thorvaldsen’s collection includes a drawing of HylasXXXIX that has been tentatively attributed to Koch, while paintings, watercolors, and drawings with the motif that are clearly by Koch are found in several elsewhere, including at StädelXL in Frankfurt. One of the first versions of the painting with Hylas and the river nymphs must be the one purchased by the German diplomat, archaeologist etc. August Kestner in 1832, which is found at Städel today. Accordingly, the artwork mentioned above and described in Koch’s letter to Thorvaldsen was presumably a replica or watercolor version of the motifXLI. It is also possible, however, that it could be a different painting—one that was found in Dresden before World War II, and has since disappeared—which was presumably an even older version of the paintingXLII. Whatever the case may be, it is clear that by the early 1830s, both Koch and Thorvaldsen had worked with the motif and mutually inspired one another.

Joseph Anton Koch: Hylas and the Water Nymphs, s.a. The attribution to Koch is uncertain. Possibly after Koch. Pen, black ink and brown wash on paper mounted on pasteboard. 144×191 mm. D1837.

Bertel Thorvaldsen: Hylas and the Water Nymphs, c. 1832. Marble. 40,7×76,0 cm. A482.

Bertel Thorvaldsen: Hylas and the Water Nymphs, 1833. Marble. 68,0×109,5 cm. A484.

Bertel Thorvaldsen: Hylas and the Water Nymphs, 1807-1810. Carbonpencil heightened with white on brownish paper. 205×238 mm. C381.

[Landschaft mit dem Raub des Hylas, 76×104, Frankfurt Städel 849]

Although several drawn landscape studies do exist from Thorvaldsen’s hand, all very different from one another, it makes good sense to regard Koch’s landscapes as another possible source of inspiration for these relief backgrounds, which are atypical for Thorvaldsen—even though he reduces them to the bare minimum, for use primarily in setting the stage: the Hylas motif requires a riverbank to be perceived unambiguously; Daphne requires the particular tree into which she is gradually transformed in Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Bertel Thorvaldsen: Christ at Emmaus, 1818. Plaster. 63,0×28,5 cm. A562.

In Thorvaldsen’s 1818 relief Christ in Emmaus, A562, the scene is set simply and efficiently: in the background, a palm tree and two cypresses are seen, indicating the exotic location. In the foreground of the same relief, we find a walking-stick thrown on the ground, along with a broad-brimmed hat to protect against the sun’s rays, and a cloak as a shield against the weather and the dust on the road. Taken together, these carefully selected objects tell us much about Jesus’ simple and modest life.

|

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen: Baptismal Font, Mary with Jesus and John, 1805-1807. Plaster. 77,8×72,5 cm. A555,2. | Bertel Thorvaldsen and Joseph Anton Koch: Mary with Jesus and John, 1801-1810. Black chalk on paper. 56,2×41,6 cm. Nysø129. |

On the other hand, if you compare the drawing of Mary with Jesus and John, Nysø129, mentioned initially (realized jointly by Koch and Thorvaldsen) with Thorvaldsen’s own reliefs with the same motifXLIII, the latter’s pure backgrounds are striking. Here landscape scenography is not needed for the viewer to perceive the motif. Rather, the viewer is more than free to set Thorvaldsen’s figures against a fantasized Arcadian background like the one the artists experienced in the area surrounding Rome, and which Koch synthesized in his landscapesXLIV.

According to KochXLV, the landscape around Olevano had a “primitive character [of nature], as one can imagine it when reading the Bible or Homer.” Put briefly, the area seemed to be the natural, unspoiled stage curtain for the ideal figures of antiquity and Christianity, and so acquired a status, for Koch, similar to that of the Swiss landscape, whose untouched natural areas affected him as a landscape of freedom, places where freedom and original being could thriveXLVI.

Joseph Anton Koch: Landscape from Olevano, to the right a self-portrait, c. 1823. Oil on wood. 35,3×47,7 cm. B127.

The simple life in compact with nature, as it unfolds in the painting Landscape from Olevano, to the right a Self-Portrait, B127, can be perceived as accentuating the importance of the landscape for the new, free human life. What is more, Koch included his own portrait in the painting’s right-hand side—with a walking-stick, and relaxing with his pipe: This is his landscape, and his painting’s representation of interaction between ancient, unspoiled nature and humanity’s healthy life becomes his contribution to the liberation and education of his contemporaries as citizens of the world.

With this, Henriette Herz’s description of Koch’s and Thorvaldsen’s personal originality and inner health, cited at the start of this article, acquires a new and tangible meaning: the personalities and works of Koch and Thorvaldsen had an influence on Herz that is comparable to the influence that the landscape of Olevano had on Koch.

What was it, then, that the two artists accomplished through their art—and how does their achievement befit their ideals of the rights and free development of individual human beings? At root, their accomplishment relates to the ability to reflect and create works of art that stimulate the individual’s capacity for independent thinking.

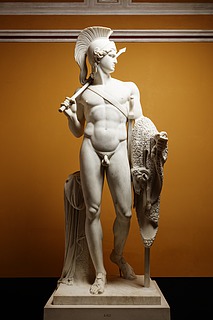

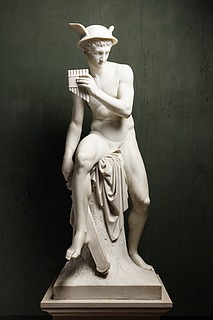

As a landscape painter, Koch naturally let the landscape itself be his main motive. The figures in his paintings often seem small and, at first glance, insignificant within their large, ideal landscapes—almost as if they were bit characters introduced for the sake of perspective. On closer reflection, however, the plot can be dramatic, as in the case of Hylas; and a surprising contrast emerges between the peaceful and grandly eternal feeling of the landscape and the momentary intensity of the plot. Meanwhile, a similar contrast, albeit of a different sort, is experienced in many of Thorvaldsen’s mythological representations. Here the characters are often depicted at a calm, reflective moment just before, or just after, a dramatic climax: the king’s son Jason, who has just conquered the Golden Fleece with cunning and deceit, just prior to his representation by Thorvaldsen; and the god Mercury, who in the very next moment will slay and kill the hundred-eyed monster Argus. We are left as spectators in a similar state of teetering between the marked tranquility that we see with our eyes and deed, often a violent one, that we know with our intellect has taken place, or soon will.

|

|

| Jason with the Golden Fleece, A822. | Mercury about to Kill Argus, A873. |

There is thus something fundamentally comparable in Koch’s and Thorvaldsen’s ways of appealing to the viewer: their works demand, in order to be understood and redeemed on a higher level, a thorough contemplation combined with imagination, empathy, and knowledge of mythology by the viewers themselves. It is this mix of cognitive activities that builds up the experience of the work; and by the same token, this experience of art builds up the viewers themselves as reflective human beings in their own right.

It is also possible to draw parallels between the two artists on another level. Koch attempted to paint the world’s “skeleton” or “body,” whose presence is evident underneath the landscape’s vegetation in the form of cliff faces, valleys, mountains, and hills. Or as the German draftsman, lithographer, and art historian C. F. Rumohr put itXLVII, Koch attempted to give “definitiveness, character, and body to the forms of the earth.”

It was in Koch’s time that interest in geology—or “geognosy”, as it was originally called—had its first heyday; and a concern for structure and surfaces of the earth is clearly evident in Koch’s approach to painted landscapesXLVIII.

This interest has much in common with the prevailing view of classical antiquity in Koch’s and Thorvaldsen’s day, which focused on the marked sense in ancient (here primarily Hellenistic) works of “the body under the skin”—its skeleton, muscles, and tendons—and was simultaneously critical of contemporary sculptors. There are signs that Thorvaldsen, too, tried to approach this ideal of a subtle representation of the human body more and more closely. A contemporary diary entry by the Scottish Lord Minto, aka Gilbert Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound, articulates this ideal in its uttermost potency: namely, that in the sculptures of antiquity, the underlying play of muscles was realized so subtly that it was necessary to touch the works physically in order to complete the eye’s perception of all that lies under the skin of the human body. In his diary entry, Lord Minto describes how, after having visited the workshops of both the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova and Thorvaldsen (and after having works by both sculptors fail the “touch test”), he found that Thorvaldsen, at that point in time, disagreed with him about the very premise of his reflectionsXLIX :

In conversing with Thorwaldson of the minute and imperceptible touches which I think must contribute much to the inimitable beauty of the old statues, he did not appear to think that any inequality of surface could be so slight as to escape our sight in proper lights. Yet my own impression remains, that in passing the hand over the dying gladiator I can perceive an undulation of surface expressing to the touch the presence of muscles &c. which, being in a state of response or deeply seated, could not without exaggeration be distinctly expressed to the eye. In many modern statues the contours of the parts are most delicately expressed with anatomical truth; but in passing my hand over them I feel nothing but what I can see. In an ancient statue every muscle which, in a state of exertion could be seen, is, when in rest, still expressed by, to the eye, an imperceptible undulation of surface; which, tho only to be detected by passing the hand over it, must add to the truth and effect of the figure.

This diary entry is dated January 7, 1822. We know that later, in the mid-1830s, Thorvaldsen reworked his original model of Jason with the Golden Fleece, A52, from 1803, which had otherwise been praised to the skies, in part by adding extra plaster to the figure, particularly on the knee and breast. In the summer of 1836, the architect of Thorvaldsens Museum, Gottlieb Bindesbøll, explained part of the reason for this as follows in a letter to his brotherL :

… He has changed his Jason a good deal … he has covered the whole body with plaster and reworked it entirely, there are many who are in doubt whether it has gotten better tha[n] before, and when one asks why he is doing this, he says[:] but it looks like armor, and not like meat.

In her article “The Torchlight Visit,”LI Claudia Mattos considers this theme in a larger theoretical, perception-historical, and museological perspective, which is unfortunately too expansive to enter into here. It should be mentioned, however, that in her article she citesLII the same Lord Minto as having claimed that experiencing statues by torchlight can make underlying structures that are otherwise invisible to the eye visible, and can awaken dead sculptures “to life.”

Thorvaldsen was highly regarded as a “torchbearer.”LIII It thus seems plausible that the above theory of the body’s invisible underlying layers, or at least awareness of a greater articulation of the body’s forms, especially in Hellenistic works, nonetheless influenced his decision to rework his youthful masterpiece in line with the latest knowledge.

Such work on surfaces in both Koch and Thorvaldsen can serve as the basis for another fruitful comparison. Koch insisted on omitting what his friend and colleague Ludwig Richter calledLIV “Knalleffekt [blowoff],” visible among French artists and certain Italians, namely, the use of impasto painting and atmospheric illusion effects such as aerial perspectives, etc. Koch is himself citedLV as having declared that “botched attempts and effects counted only as means to prize the wondrous cipher from nature and reproduce God’s thoughts, and not as the main thing, as they are for many artists today.” His own paintings consist of simplified syntheses of his sketches, of which only the most essential are excerpted and arrangedLVI.

For his part, Thorvaldsen was often contrasted to Canova, and was chided by critics for his lack of attention to surfaces (by the aforementioned Lord Minto, among others). Unlike Thorvaldsen, Canova often polished his marble works and rubbed them with wax in order to give the stone a more skin-like, translucent appearance. Thorvaldsen mainly left his marble works matte, with only a few highlights, so that the reflection and interplay between light and stone had the only effect in the spaceLVII. Instead, in Thorvaldsen’s works the focus is more on internal contrasts, i.e., on contrasts between the reproduction of various structures and surface types—for example, rough bark on a tree stump; soft fur; rock that is weathered, hard, or soft; naked skin. In both Koch’s and Thorvaldsen’s case, then, there is little “blowoff” and much more focus on what one might call, almost modernistically, the individual objects’ own characters and expressions. And this does not make the result any less sensuous—on the contrary, one can claim—for their artworks’ seemingly “dry” portrayals of body and landscape leave more space, precisely because of their “dryness,” for the spectator’s own associations.

Where does all this focus on structures, simplicity, and understatement lead, in contrast to polishing, waxing, impasto painting, and atmospheric effects? And what was the significance of the landscape around Rome—and especially, for Koch, the Olevano area—for what the artists wished to advance through their art and way of life?

With regard to Olevano specifically, it should be noted that while it is overwhelmingly likely that Thorvaldsen also visited there, this has not yet been provenLVIII. Rumor has it, meanwhile, that evidence in the form of Thorvaldsen’s signature was found in a now-vanished guest book from Casa Baldi in Olevano; but this cannot be confirmed either. On the other hand, it is known with certainty that Thorvaldsen passed through and stayed at many other sites in the area surrounding Rome, such as Ariccia, the Cervaro grottoes, Tivoli, and GenzanoLIX. And just like Koch (as can be seen in the modest self-portrait on the side of his painting of the landscape from Olevano), Thorvaldsen also cultivated a simple wanderer’s joys, doing so deliberately despite being unmistakably well-off. This is supported, among much other evidence, by an accountLX furnished in the summer of 1842 by the Danish sculptor C. F. Holbech. At a gathering hosted by the Italian count and sculptor Antonio Savorelli, a gentleman of the company, in conversation with Thorvaldsen, asked him: “Cavaliere, siete voi pure cavaleriste?” To which Thorvaldsen laconically replied: “Non Signore, sono somaristo.” Put briefly, Thorvaldsen said he preferred to be a donkey-rider than a horseman—a reply with obvious political undertones, and quite provocative ones at that. Holbech highlighted this conversation as illustrating that Thorvaldsen was still as sharp as a tack mentally. Between the lines, it emerges that the sculptor was especially conscious of his role as spokesman for the simple, unaffected human being: for him, humble donkey rides were clearly preferable to aristocratic traditions with fine riding horses, however acclaimedLXI. To be wanderers and donkey-riders was not merely to choose another form of transport; it was a statement and a form of lifeLXII.

As has become clear in the foregoing, these two artists shared both political and artistic traits. Both aimed to represent what is timeless, ideal, and universally valid in a manner that required their audience to be active mental co-creators. For both, the landscape surrounding Rome, and Olevano in particular—whether or not this was visible in the finished works—formed the perfect stage curtain for the mythological figures that they used precisely in order to personify existential and commonly human concepts and issues. As the citation from Herz used in the introduction to this article reveals, Koch and Thorvaldsen did this simply and effectively, thereby setting examples for a whole generation of international painters and sculptors to follow: artists who, like Koch and Thorvaldsen, went out to the countryside surrounding Rome in a search for pure, unspoiled authenticity. One can perhaps speak of a kind of previtalism in both Thorvaldsen and Koch, which for both presumably had its roots in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s (1712–1778) vision of the enlightened human being in compact with nature. Subsequently, Koch and Thorvaldsen’s artistic successors came increasingly to hunt for what is local and close to the people; and Olevano in particular came to enjoy a new status as an artists’ paradiseLXIII.

Thorvaldsen’s well-known and well-visited collection of paintings—including motifs by Koch and others from the area around Olevano—undoubtedly contributed, along with his large international network of artists, to the fact that it was not merely the oft-mentioned German-speaking colony of artists, but also others, who went out to explore the area surrounding Rome. It thus makes sense to conclude the present article with a watercolor, presumably made by the Danish artist P. C. Skovgaard in 1869, which depicts three artistic successors to Koch and Thorvaldsen—Wilhelm Marstrand, P.C. Skovgaard og Adolph Kittendorf (1820-1902) —riding on donkeys between Subiaco and Civitella.

P.C. Skovgaard [attributed]: Marstrand, Skovgaard, and Kittendorf on Donkeys Towards Civitella and Olevano, 1869. Watercolor on paper. 62×132 mm. Private collection.

Last updated 11.08.2025

Cited following J. Fürst (ed.): Henriette Herz. Ihr Leben und ihre Erinnerungen, Berlin 1850, p. 229. Translation by David Possen.

With regard to Thorvaldsen, see, e.g., Kira Kofoed, Thorvaldsen’s Spoken and Written Language, along with documents associated with the topic “Characterizations of Thorvaldsen,” arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/topics/characterizations-of-thorvaldsen.

Cf., e.g., Koch, Moderne Kunstchronik. Briefe zweier Freunde in Rom und der Tatarei über das moderne Kunstleben und Treiben; oder die Rumfordische Suppe, gekocht und geschrieben von Joseph Anton Koch in Rom, (1834), with contributions by Genelli and Reinhart.

See the letter by Koch to his classmate G. F. von Fischer dated May 3, 1805, reproduced in Else Cassier, Künstlerbriefe aus dem neunzehnten Jahrhundert, Berlin 1919, pp. 106-109. See also the letter dated April 10, 1800 from the Danish doctor Poul Scheel to Thorvaldsen.

Both Koch and Thorvaldsen were among the many coauthors responsible for the critical tract Drei Schreiben aus Rom gegen Kunstschreiberei in Deutschland, Dresden 1833 (https://sammlungen.ulb.uni-muenster.de/ob/content/titleinfo/587088). Thorvaldsen was dyslexic, and presumably for that reason, had no desire to write any more than absolutely necessary; cf. Jørn Lund, Sproget i Thorvaldsens dagbog og tidlige breve in Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen 2008, p. 51-60, along with Kira Kofoed, Thorvaldsens tale- og skriftsprog, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2009.

For examples of this, see Ernst Jonas Bencard’s notes on Johanna Steinheim’s account of Thorvaldsen insisting on shaking hands with everyone, regardless of rank or position, in her letter to Raphael Hanno dated October 29, 1842, along with Frederikke Wallick’s October 1842 description of the same behavior.

Thorvaldsen’s economic success presumably explains much of why he was able to act on so many of his liberal ideals. On this see especially Nanna Kronberg Frederiksen, Christian 8.’s Loan from Thorvaldsen, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2014.

The reason for his expulsion has not yet been determined with certainty. It may have been because Carsten refused to work with oil paints, as was required, but insisted on using drawing paper; it may have been that he did not consider a silver medal a sufficient acknowledgment of his achievement; or it may have been that he did not believe that the student who received the gold medal had been selected fairly. For more on this, see Gertrud With, “Et trekløver – Asmus Jacob Carstens, Joseph Anton Koch og Bertel Thorvaldsen i Rom,” in Stig Miss and Gertrud With (eds), Asmus Jacob Carstens og Joseph Anton Kochs værker i Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen 2000, p. 13.

Cited following Carl Ludwig Fernow, “Leben des Künstlers Asmus Jakob Carstens, ein Beitrag zur Kunstgeschichte des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts”, Leipzig 1806, p. 205, and Rudolf Zeitler: “Der neue Klassizismus des späten 18. Jahrhunderts – Kunst des Aufbruchs”, in Asmus Jakob Carstens. Goethes Erwerbungen für Weimar, Schleswig 1992, p. 9. Translation by David Possen.

On this see Ernst Jonas Bencard, A Free Man. Thorvaldsen’s Continuance in Rome, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2009, and Karen Benedicte Busk Jepsen, Caffè Greco: Art Temple, Post Office and Cosmopolitan Sanctuary, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2014.

Competition for success and recognition among the artists could also be fierce, and at times involved coarse humor and tenacity. This is evident, for example, in an anecdote that is told variously by the English sculptor John Gibson (1790–1866) and the Danish professor and author N. C. L. Abrahams (1798–1870), but which seems to have a kernel of truth to it. The anecdote concerns the German painter Ernst Zacharias Platner (1773–1855), and indirectly claims to explain the reason why Platner abandoned his métier as a practicing artist in favor of a career as an art critic and diplomat. According to both accounts, Platner had asked a number of colleagues and connoisseurs to provide critical feedback on his most recent large sketch for a painting. Abrahams names Joseph Anton Koch as the main actor, while Gibson highlights Thorvaldsen and the German painter Peter von Cornelius (1783-1864). True or false, read Gibson’s entertaining narration of the episode here. Cited from Gibson’s autobiography, T. Matthews (ed.), The Biography of John Gibson, R. A., Sculptor, Rome, London 1911, pp. 221–222.

The precise address was Via Sistina 141, 2nd floor. Cf. Friedrich Noack, Das Deutschtum in Rom seit dem Ausgang des Mittelalters, vol. 2, Leipzig 1927, p. 594. At the time, however, the street was called “Via Felice” or “Strada Felice.” For further documentation, see the letter dated November 1, 1803 , from Wilhelm von Humboldt to Thorvaldsen, Gemeente Amsterdam, Bibliotheek der Universiteit, Afdeeling: Handschriften, Geschenk van den Heer P. A. Diederichs. No. 7.3 Fp 3. Here the address appears as follows: “Al/ Signor Thorwaldsen, / Scultore Danese / Strada Felice, / il 3za portino / averti la piazza / Barberini.” See also J.M. Thiele, Thorvaldsens Ungdomshistorie. 1770-1804, Copenhagen 1851, p. 164: “… Thorvaldsen seems to have formed the closest bond with Joseph Koch; the two soon moved in together and lived in one of the last houses on the left side in Via Felice, close to Piazza Barberina, where an old and rather elegant Padrona di casa, by the name of Ursula, kept house for them”; see also ibid., p. 175, and Otto R. von Lutterotti, Joseph Anton Koch 1768-1839. Leben und Werk mit einem vollständigen Werkverzeichnis, Vienna and Munich 1985, p. 11 and p. 38.

Cf. Christian von Holst: Joseph Anton Koch. 1768-1839. Ansichten der Natur, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 1989, p. 11. See also the letter dated April 10, 1800, from Poul Scheel til Thorvaldsen, which mentions not only a female friend of Koch’s, Domenica Giusti, but presumably also Koch’s lover Maria Angela Sodi.

J. L. Lund, Portræt af Orsola Polverini Narlinghi, Thorvaldsens værtinde i Rom, B448. Two of Thorvaldsen’s drawings also apparently represent Orsola Polverini Narlingh, namely, C764r and C803r.

For more on this society, see, e.g., H.C. Andersen, Mit livs eventyr, Copenhagen 1951, chapter 6, pp. 164–165; Gerhard Bott and Heinz Spielmann (ed.), Künstlerleben in Rom. Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), Nuremberg 1991, pp. 473–490; Franz von Gaudy, “Reise- und Lebensbilder,” in Morgenblatt für gebildete Leser, nos. 135–138 (pp. 537–538, 542–543, 545–546 and 550–551); Rita Giuliani, “Thorvaldsen e la colonia romana degli artisti russi,” in Patrick Kragelund og Mogens Nykjær (ed.), THORVALDSEN L’AMBIENTE L’INFLUSSO IL MITO, Rome 1991, pp. 131–147; Hjördis Jahnecke, Die Breitenburg und ihre Gärten im Wandel der Jahrhunderte, Kiel 1999, p. 206; Friedrich Noack, Das Deutschtum in Rom seit dem Ausgang des Mittelalters, vol. 1, Berlin and Leipzig 1927, pp. 506-525; Friedrich Noack, Deutsches Leben in Rom 1700 bis 1900, Stuttgart and Berlin 1907, pp. 238–262; Domenico Riccardi, Olevano e i suoi Pittori, Rome 2004, pp. 28–31.

Precisely when these grottos were discovered by artist-travellers has not been determined with certainty. On this see also Cornelia Reiter, “Nature as Ideal: Drawings by Joseph Anton Koch and Johann Christian Reinhart,” in Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol. 49, no. 1 (January 2014), New York 2014, p. 208.

Cf. 29.12.1825.

The list in question is presumably identical to an previously undated list in The Thorvaldsens Museum Archives, now dated presumaly around 29.12.1825.

Cf. M17,14. The same description is also given, with a few variations, in M17,12 and M17,21, among others. Translation by David Possen.

In the past, neither collaboration by several artists on a single work nor the production of copies or replicas were unpopular or regarded as unusual. If one could not obtain the original, a replica or copy was often a fine substitute; what mattered most was the motif and the quality of execution. In both painting and sculpture, however, this very reproductive aspect has been challenged greatly since the mid-19th century, on account of the increasing focus on originality; and for that same reason, numerous copies and replicas both of Thorvaldsen’s own works and from his collections were sold at an auction at Thorvaldsens Museum in 1849, cf. 1.10.1849, 1.10.1849. On this see also Kira Kofoed, Thorvaldsen’s Collection of Paintings − a Collection with a Significant Lack, arkivet.thorvaldensmuseum.dk, 2015, and Kira Kofoed, Prolific Producer or Strategic Genius?, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2014.

Cf. letter dated 7.4.1822 from Koch to Thorvaldsen.

Cf. Giambattista Bassi’s letter to Thorvaldsen dated August 17, 1828, in The Thorvaldsens Museum Archives, m13 1828, nr. 82. It should be emphasized that no comparative studies of prices have been conducted to prove or disprove this thesis. We do know, however, from Christine Stampe’s unpublished manuscript of her memoirs, that Koch’s son-in-law Johann Michael Wittmer also had a fracas with Thorvaldsen when he wished to sell a painting to him and claimed that the sculptor’s offer was too low. Thorvaldsen rebuffed Wittmer by telling him that he could take his painting and sell it for more, if he could. Stampe’s account will be published later in 2018 at The Thorvaldsens Museum Archives.dk.

Cf. Otto R. von Lutterotti, Joseph Anton Koch 1768-1839. Leben und Werk mit einem vollständigen Werkverzeichnis, Vienna and Munich 1985, p. 39; Christian von Holst, Joseph Anton Koch. 1768-1839. Ansichten der Natur, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart 1989, p. 12.

The copies made by Koch reached Denmark together with Thorvaldsen’s own copies and Carstens’ original drawings. It has subsequently been debated which artist was responsible for which works. For more on this, see Gertrud With, “Et trekløver—Asmus Jacob Carstens, Joseph Anton Koch og Bertel Thorvaldsen i Rom,” in Stig Miss and Gertrud With (eds), Asmus Jacob Carstens og Joseph Anton Kochs værker i Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen 2000, pp. 22-24.

On this see Ernst Jonas Bencard, Thorvaldsen’s reliefs in Palazzo Giraud-Torlonia, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2014; Just Mathias Thiele, Thorvaldsen i Rom. 1819-1839, Copenhagen 1854, p. 328; and Chr. Bruun & L. P. Fenger, Thorvaldsens Musæums Historie, Copenhagen 1892, p. 3.

Cf. Jürgen Wittstock, Geschichte der Deutschen und Skandinavischen Thorvaldsen-Rezeption bis zur Jahresmitte 1819, [Dissertation] Hamburg 1975, p. 40; and Monika von Wild, George Augustus Wallis (1761-1847). Englischer Landschaftsmaler. Monographie und Oeuvrekatalog, Frankfurt am Main 1996, pp. 129-146.

For more on this, see Marie Lødrup Bang: ‘Joseph Anton Kochs “Lauterbrunnental” og Johan Christian Dahl’, in Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen 1989, pp. 237-246.

The drawing in question is Mary with Jesus and John, NysøG. The drawing was presumably given in 1818 to the Scotswoman Frances Mackenzie, Thorvaldsen’s then lover; after his somewhat unbecoming break with her, she sent it back to him. Many years later, on Christmas in 1841, the sculptor presented the painting to his friend, the Danish baroness Christine Stampe, cf. Rigmor Stampe (ed.): Baronesse Stampes Erindringer om Thorvaldsen, Copenhagen 1912, p. 161.

Cf. Bacchus offers Cupid a Drink, C844. The drawing is a copy of a drawing by Thorvaldsen with the same motif, C830r. On the reverse side of C844, a note by an unknown hand reads: “Drawn by A. Thorvaldsen in Rome for use by the landscape painter J. Koch in one of his landscapes.” This information, however, has not yet been verified definitively. The same holds for Lutterotti Z 505.

On this see especially Stig Miss and Gertrud With (eds.), Asmus Jacob Carstens og Joseph Anton Kochs værker i Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen 2000.

The Dance of the Muses on Helicon, 1806, unfinished marble version, 73×160 cm, A705. The original model from 1804 is unknown today, which is why it is impossible to verify the precise number of muses.

Joseph Anton Koch: Apollo among the Thessalian shepherds, 1834, Neue Pinakotek München, inv. no. L.1834.

In Greek mythology, Hylas is a young prince and squire to Heracles who is abducted by water-nymphs while fetching water from a river.

See, e.g., Apollo among the Thessalian Shepherds, B125, Noah’s Sacrifice after the Flood, B129, or Landscape from Olevano, to the right a self-portrait, B127.

Alexander the Great’s Entry into Babylon, 1812, plaster cast, 106.5×3446.0 cm, A503.

Hylas and the Water Nymphs, ca. 1832, Marble. 40.7×76.0 cm, A482; Original model A483, 1831. And Hylas and the Water Nymphs, 1833. Marble. 68.0×109.5 cm, A484. Original model A485, 1833.

On this see Jørgen Birkedal Hartmann, “Thorvaldsen nel regno delle ninfe,” in Studi offerti a Giovanni incisa della Rochetta, Rome 1973, p. 213.

Cf. Koch’s letter to Thorvaldsen dated 18.4.1833.

Hylas and the Water Nymphs, D1837. The drawing was first incorporated into the Museum’s collections in 1947, but likely derives originally from Thorvaldsen himself; cf. Tegningsregistranten, THM. See also Lutterotti, Z 511a.

Landschaft mit dem Raub des Hylas, 1832. Oil on canvas, 76×104 cm.,” Frankfurt Städel 849: https://sammlung.staedelmuseum.de/de/werk/landschaft-mit-dem-raub-des-hylas

Koch made many versions of this painting; on this see Otto R. von Lutterotti, Joseph Anton Koch 1768-1839. Leben und Werk mit einem vollständigen Werkverzeichnis, Vienna and Munich 1985, G 77, Z 292, Z 70, Z 629, Z 385, Z 422, Z 122, Z 604, Z 1119, Z 56, Z 99, Z 1089, Z 689, and Z 1125. See also Jørgen Birkedal Hartmann, “Thorvaldsen nel regno delle ninfe,” in Studi offerti a Giovanni incisa della Rochetta, Rome 1973, p. 212, note 65.

Cf. Lutterotti, op. cit., p. 286, G 16a.

Mary with Jesus and John, partly as an element in Baptismal Font, A555,2, 1805-1807, original model, plaster, 77.8×72.5 cm, and partly as an individual relief, A556, original model, plaster, 57×52 cm.

On this see also Lulu Salto Stephensen, “Thorvaldsen and the Invisible Landscape,” in Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum, 1989, pp. 104-112.

Cf. Lutterotti, op. cit., p. 61, along with note 138, cited following the letter from Koch to Georg Chr. Fische, dated May 26, 1826. See also Marie Lødrup Bang, “Joseph Anton Kochs ‘Lauterbrunnental’ og Johan Christian Dahl,” in Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen 1989, p. 237-246.

Cf. Joseph Anton Koch. Ansichten der Natur, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart 1989, p. 7.

Cited following Lutterotti, op. cit., p. 65; originally published in Rumohrs, Drei Reisen nach Italien, 1832. See also Marie Lødrup Bang: ‘Joseph Anton Kochs “Lauterbrunnental” og Johan Christian Dahl’, in: Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum, København 1989, p. 237-246.

The landscapes of both Koch and Caspar David Friedrich have been regarded as epitomizing the German geologist and mineralogist Abraham Gottlob Werner’s (1749-1817) geonostic theories; cf. Marie Lødrup Bang, op. cit., note 19, p. 240.

Gilbert Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound kept a diary during his stay in Rome in 1821–1822. This diary is here cited following Ian Gordon Brown, “Canova, Thorvaldsen and the Ancients. A Scottish view of Sculpture in Rome, 1821-1822,” in Antonio Canova. The Three Graces, Edinburgh 1995, pp. 73–80. The original diary is preserved in the National Library of Scotland, MSS 11986-7. The present excerpt may also be read in The Thorvaldsens Museum Archives

See the letter dated July 28, 1836, from Gottlieb Bindesbøll to his brother Severin Bindesbøll, printed in the journal Artes I, pp. 176–177. On this see also Kira Kofoed, “Jason and the Hope Commission,” arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2009. Translation by David Possen.

Claudia Mattos, “The Torchlight Visit: Guiding the Eye through Late-Eighteenth- and Early-Nineteenth-Century Antique Sculpture Galleries,” in Carol Adlam and Juliet Simpson (eds), Critical Exchange: Art Criticism of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries in Russia and Western Europe, Oxford 2009.

Claudia Mattos, “The Torchlight Visit,” op. cit., p. 142.

See, e.g., the letter dated 17.1.1819 from Francisca Caspers to Charlotte Thierry.

Ludwig Richter, Lebenserinnerungen eines deutschen Malers, Leipzig 1950, here cited following Marie Lødrup Bang, op. cit., p. 242.

Ein deutsches Künstlerleben, ed. Bernt Grönvold, Leipzig 1915, p. 118, here cited following Marie Lødrup Bang, op. cit., note 31, p. 242.

On this see Reiter, op. cit., along with Lulu Salto Stephensen, op. cit., pp. 104–106.

On this see Sigurd Schultz, “Thorvaldsen og Marmoret,” in Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum, 1944, pp. 91–101.

I am grateful to Jytte W. Keldborg for this information. Thorvaldsen’s name is also included in Coriolano Belloni, I Pittori di Olevano, Rome 1970, p. 56, but because no source is cited there, it must be regarded as an unproven claim for now.

For more on this, see the Thorvaldsen chronology. Search for instance specifically for Ariccia, Albano, or Tivoli.

This account is included in a report on Thorvaldsen’s doings sent to the baroness Christine Stampe, and dated September 29, 1842 the section under the date July 31, 1842).

For an example of such a donkey-riding excursion, see, e.g., the diary of Peter Brønnum Scavenius, in Peder Brønnum Scavenius’ private archive, the Danish National Archives; published in The Thorvaldsens Museum Archives at arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/documents/ea9683.

Compare Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel Идио́т [The Idiot], Moscow 1868-69, where the donkey is praised by the main character (the naïve but solemnly good Prince Lev Nikolayevich Myshkin). The donkey also serves to this day as the emblem of the U.S. Democratic Party.

On this see, e.g., Jytte Keldborg, Gli artisti danesi ad Olevano e dintorni dall’”Età dell’Oro” fin dentro il XXI secolo / Danish artists in Olevano Romano and its surrounding area from the “Golden Age” into the 21st century, Olevano 2011.