The present article illuminates the background and history of one of Thorvaldsen’s less-known public monuments—his monument to Thomas Maitland, Great Britain’s Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands, which was erected on the island of Zante (Zakynthos) in 1820, when the Ionian Islands were a British protectorate. This monument consisted of a colossal bust of Maitland in bronze, cf. A258, together with the relief Minerva, Truth and Lie, cf. A600, set on the bust’s marble pedestal. It no longer exists in its entirety, let alone at its original site. Although the commission was specified as a highly constrained task, Thorvaldsen insisted on his artistic freedom, making significant changes to the relief’s motif. This commission is also an example of how Thorvaldsen was hired in order to grant his contemporaries, by means of his portraits, access to a coveted ideal and to the value of antiquity. Thanks to a review of the relevant documents, the relief—which for many years went under the title Minerva, virtue and vice—has had its original meaning restored, and is now called Minerva, Truth and Lie. Nevertheless, the possibility cannot be excluded that the relief was intended to convey both meanings.

In a corner of the foyer of Thorvaldsens Museum, behind the equestrian statue of Emperor Maximilian I, there stands a male bust on a pedestal. The pedestal itself is the setting for a relief with three female figures. This arrangement does not call much attention to itself, and has not done so in many years—not, at least, since the art historian Else Kai Sass published her major three-volume work, in which the bust is mentioned. But as will here become clear, the story behind these works is hardly uninteresting: it involves political intrigues, spoils of war, torpedoed warships, and a possibly illegal resale of artistic treasures.

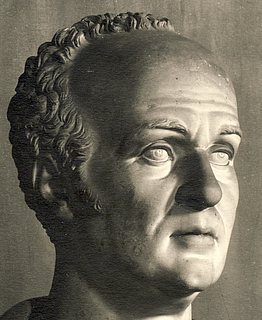

Thorvaldsen’s models for his monument to Thomas Maitland, the British Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands, on display in the foyer of Thorvaldsens Museum.

The monument to Thomas Maitland appears to have been commissioned as part of a large-scale gambit of flattery in 1817. The source of the commission was a circle of Ionian gentry who hoped, according to their critics, to gain privileges for themselves by honoring Maitland. According to these same critics, the gambit succeededI. The political background for these events was the aftermath of the 1815 Congress of Vienna, when the Ionian IslandsII were granted communal autonomy, albeit only as a protectorate of Great Britain, until their absorption into Greece in 1864. From 1809 until 1814 the islands, which had a long history of changing hands, were occupied by the British; and it was this occupation that was replaced by the islands’ new autonomy as a British protectorate. The agreement on autonomy was ratified on August 26, 1817 in the Maitland Constitution, which was named for the very same Scotsman, Thomas Maitland, who was the subject of Thorvaldsen’s bust. This former soldier and general became the islands’ first Lord High Commissioner, i.e., the direct representative of the British king. Prior to this, he had been governor of Malta from 1813.

The monument to Maitland was supposed to have been erected in the city of Zante, on the island of the same name. According to ThieleIII, the monument was commissioned by a collection of Ionian noblemen out of a desire to thank Maitland for having granted the Ionian Islands both a constitution and a university. Maitland had been appointed Lord High Commissioner in 1815, and did indeed write a constitution that was ratified in 1817—the same year in which Thorvaldsen became involved. The university, on the other hand, was only founded in 1824; so the monument was presumably an artifact of equal parts gratitude and of hope.

The inscription on the pedestal lends support to the notion that the monument was more concerned with hopes and expectations than with acknowledgment of the results that Maitland had already achieved as a statesman (here in English translation):

THOMAS MAITLAND

ZAKYNTHIANS

FOR THE GOOD HOPES

1817IV

Maitland’s monument, as it looked in its entirety while installed in Zante on the island of the same name. The photograph is reproduced following Ludwig Salvator, op. cit., vol. I, p. 13. Salvator, however, claimed that the bust had been produced by the local sculptor Paolo Prossalendi.

A speech held in the British House of Commons on 7.6.1821V by MP Joseph Hume (1777–1855) insinuates that the monument to Maitland was more an expression of flattery and hope for the protection of their privileges by anxious Ionians than a genuinely well-grounded tribute to Maitland’s governance. “The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George,” mentioned in the speech, is a civil chivalric order that had recently been founded, on April 28, 1818, by the future King George IV (1762–1830), when he was acting as Prince Regent for his mentally ill father, King George III, as a mode of rewarding citizens of British protectorates—and which Maitland had worked to establishVI:

“MaitlandVII left Corfu for England, to prepare and concert with government the constitution for the islands. On his return he was received with addresses and adulatory effusions of all kinds, though he had expressly stated in his correspondence his utter detestation of every thing like external pomp and parade. These addresses were got up by persons always ready to worship the rising sun, to pay a dastardly court to authority; and the flattery was, in truth, of the most nauseating kind. In a short time other public testimonies were voted; a triumphal arch was subscribed For in Corfu, to perpetuate services of scarcely two months’ continuance. A colossal statue of Sir T. Maitland was raised in Cephalonia; a bust of him, by CanovaVIII, was placed in a public situation in Zante. In Ithaca a monument was inscribed to him, and in Santa Maura he was honoured with a second triumphal arch. The consequence was, that those who had been active in these testimonials were selected for reward and office, without mentioning the bands of knights of the orders of St. Michael and St. George …”

While Maitland made sure that new roads and lighthouses were built on the islands, he simultaneously secured extensive powers for himself, in part by means of the constitution that he himself had prepared. Partly because of tax increases, Maitland was accused of abusing his position. During the Greek War of Independence (1821-1829), Maitland insisted on neutrality for the Ionian Islands in line with that of Great Britain, and thereby alienated the local Greek population, as well as other Philhellenes who supported the notion of an independent Greek state.

Maitland went by the name King TomIX, which speaks volumes about his dominance as Lord High Commissioner. One contemporaryX characterization of him testifies that he was a complex and principled man:

“Sir Thomas was a mortal of strange humours and eccentric habits; but it is due to the memory of that able man to say that his government bore the impression of his strong mind. “King Tom” was a rock; a rock on which you might be saved or be dashed to pieces, but always a rockXI.”

Thorvaldsen’s colossal bust of Thomas Maitland, A258, produced in 1818 on the basis of the plaster cast of Paolo Prossalendi’s bust of Maitland, G342. The bust was cast in bronze and set on a pedestal in Zante in 1820. It remained there until World War II, when it vanished.

Thorvaldsen was contacted about the monument by the Greek sculptor Paolo Prossalendi, who had become acquainted with Thorvaldsen during his own visit to Rome around 1810. Prossalendi’s letter, dated 3.5.1817, suggests that he was used as a wedge in a campaign to encourage the celebrated and busy Thorvaldsen to view this potential commission favorably. In the event, Prossalendi’s letter was followed by a missive dated no later than 3.5.1817 from the Ionian diplomat Dionisio Bulzo, the actual representative of the still-unknown sources of the commission. It was Bulzo who handled their correspondence about the commission’s contents—and it was similarly Bulzo who identified the third party to the commission, Spiridion Naranzi, the Russian state councillor and general counsel in Venice. Naranzi took charge of practical issues relating to costs and transportation, and in general became the caretaker for the commission.

Thorvaldsen’s assignment was very specific. There was to be a colossal bust of Maitland, in which the Lord High Commissioner was to be depicted all’eroica, i.e., “in heroic style”, i.e., clad in ancient armor, and perhaps with a fighting helmet as well; see the bust as it appears on drawing D1564. There was also to be a relief with two female figures, one representing Minerva, and the other an allegorical figure representing strength. The relief’s motif was to be a rather violent one: Minerva was to be depicted in the act of tearing a mask off of the woman’s face, revealing a skull and crossbones. This was presumably intended as a vanitas or memento mori motif, reminding the viewer that God reveals all lies and falsehood. This motif would confirm that Maitland had governed the republic in a morally defensible manner, and so could take death and the afterlife in stride when the time came.

This description of the relief’s motif was by no means alluring to Thorvaldsen, whose works are typically marked by an understated calm and a clear harmonic structure. Thorvaldsen accordingly suggestedXII the addition of a third figure, presumably with the aim of (among other things) clarifying the allegorical meaning of both what Minerva thinks right and so protects, and what she exposes and distances herself from. That this suggestion won the day is clear from the completed relief, which contains three figures, rather than two.

Thorvaldsen’s relief Minerva, Truth and Lie, A600, presents an image of Minerva, goddess of wisdom (in the middle), exposing Lie (the woman on the right), while Truth (the woman on the left) is taken under the goddess’s protection. This relief was rendered in bronze on the pedestal below the bust of Thomas Maitland.

Maitland did not sit for his bust. According to the above citation from Joseph Hume, Maitland was not directly involved in the commission at all; the Ionians prepared their displays of honor for him in his absence, and likely, according to the same Hume, against to the Lord High Commissioner’s will. The bust thus needed to be made from another model; and Thorvaldsen was indeed sent a plaster cast, G342, of another bust of Maitland. The art historian Else Kai Sass has attributed this cast with high probability to Paolo ProssalendiXIII. This surmise is supported by the fact that Prossalendi produced both a bust (in multiple versions) and a statue of MaitlandXIV, as well as by the fact that, for many years, Thorvaldsen’s bust of Maitland was taken to be a work by ProssalendiXV.

The lifelike plaster cast was sent to Thorvaldsen with the wish that the sculptor would use it as a basis for his bust, but would add his trademark: tutti qui tratti l’Ideale antico, che il prezioso suo genio le detterà.XVI

|

|

| Paolo Prossalendi was presumably himself the creator of the bust of which a plaster cast, G342, was sent to Thorvaldsen. He was to use this cast as a prototype for the commissioned colossal bust of Thomas Maitland. | Detail of Thorvaldsen’s original model of the colossal bust of Thomas Maitland, A258. Some traits have been idealized: the mouth has been made fuller, the nose clearer, the eyes larger, and the eyelids less heavy; in general, Maitland’s somewhat tired and pinched face has been lifted, smoothed out, and made grander. |

Thorvaldsen produced Maitland’s bust according to conventional standards with respect to idealization, size, and armor. Its features are more ideal than those on the plaster cast; the bust is cut off under the breast, and has been clothed in armor and an armless cape inspired by the Roman emperors.

On the other hand, the warrior’s helmet included in the proposal for the monument was not actualized. As Naranzi’s letter dated 27.4.1818 attest, Thorvaldsen instead wished to adorn the bust with a so-called civic crown (corona civica), originally a woven circlet of oak leaves awarded to Roman citizens who had exhibited extraordinary excellenceXVII. This would have represented a clear mitigation of what was otherwise to become a quite bellicose monument to the former general.

In her descriptionXVIII of the bust, Sass took the designation corona civica as a reference to a mural crown (corona muralis) of the sort found on the ancient city goddesses Cybele and Tyche. It is not known with certainty which type of crown Thorvaldsen was considering; but civic crowns, i.e., leaf garland crowns, are common in Thorvaldsen’s portraits; cf., e.g., the statue of the duke Eugène de Beauharnais, A156, the bust of Napoleon I, A252, or the statue of the poet and philosopher Friedrich Schiller, A138, as well as the preparatory models for the never-completed monument to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, A139 og A140. Mural crowns, on the other hand, are not found in Thorvaldsen’s portraits of his contemporaries, and so it is overwhelmingly likely that the crown at issue in Maitland’s case was also a leaf garland (civic) crown, even if, according to Maitland’s critics, a more massive and obvious crownXIX would have been a better fit for “King Tom.”

The final bust, in any case, has no crown at all. So either Thorvaldsen himself come to reject the idea, or Bulzo’s reply (which is mentioned elsewhere, but not extant) was negative; cf. the letter from Naranzi dated 27.4.1818. A garland with the same assocations, however, is found on the uppermost part of the bust’s pedestal; see the photograph of the remaining portion of the pedestal in the section below on the monument’s subsequent history.

In the final bust, Maitland is portrayed bareheaded—a clear toning-down of the heroic motif specified in the commission. Both the bust’s ultimate unadorned head and the suggestion of a civic crown—which would have emphasized Maitland’s status as a citizen, rather than his role as Lord High Commissioner—may be regarded as articulations of Thorvaldsen’s own democratic leanings.

Thorvaldsen was sent a so-called “painterly drawing” of the relief’s motif, which unfortunately is no longer extant, to serve as a model for it. He was then instructed not to deviate the slightest bit from the motif shown in the drawing when converting it into a reliefXX. As mentioned above, this motif was originally quite blatant, and was far afield from those that Thorvaldsen was used to working with. Specifically, Minerva, the goddess of wisdom, was supposed to rip a mask off of a woman’s face, revealing a skull and crossbones underneath.

Despite this, by the end of 1817 Thorvaldsen had negotiated the inclusion of a third figure in the reliefXXI; this was the drawing that was sent to Thorvaldsen with Naranzi’s letter dated 16.1.1818XXII. Thorvaldsen did not believe, however, that such a drawing could be converted directly into a relief, because the two media are so different from one another—a point that is repeated in Bulzo’s replyXXIII to Thorvaldsen: ... detto dissegno essendo fatto alla Pittorica ella crede di fare qualche cambiamento per reinformarsi alle leggi del Basso-relievo. It is not clear what precisely Thorvaldsen had meant by this; but contemporary reproductionsXXIV of the sculptor’s own works were often published as engravings, i.e., without the three-dimensional effect that can achieved with the shadow effects produced by gradations of light and dark areas, as is seen precisely in painterly drawings. For Thorvaldsen, in short, painterly drawings lay closer to the art of painting than to that of sculpture.

This part of the commission, too, was a highly constrained assignment; but Thorvaldsen insisted on his artistic freedom, and undertook essential changes to the relief’s motif, which ended up with three figures and a more toned-down allegory, namely, that of a Minerva who protects Truth (a half-naked young woman, elegant and calm), and who exposes Lie by pulling the veil away from her face (a covered woman, fleeing, but still beautiful).

After the negotiations with Thorvaldsen, Dionisio Bulzo describedXXV the two possible interpretations of the relief’s motif as follows. Whether it symbolizes Freedom and Slavery, or Truth and Lie, Minerva stands in the middle as the power exercising moral judgment. According to ThieleXXVI, it was Thorvaldsen’s idea to represent the two female figures on each side of Minerva as portraits of Truth and Lie, but this cannot be confirmed at present. Bulzo suggested that the women could also have represented Freedom and Slavery, but that it was up to Thorvaldsen to decide what meaning, and thereby which attributes, were to be selected:

La figura di mezzo che rappresenta Minerva conviene al mio proposto per essere il simbolo o della saggezza o della Grande Nazione ad uno degli Eroi della qualle si deve erigere questa memoria. Le due figure laterali è mia intenzione che possino indicare o la libertà e la schiavitù, o se ella crede meglio la verità e la menzogna.

Spiegatole il mio proponimento lascio alle di lei lumi il rivestirle degli attributi, e situarle nell’atteggiamento che il di lei genio puo inspirarle.XXVII

This explanation is essential, and the two proposed interpretive possibilities are likely the closest we can come to the original title of the relief, which from 1844 and onward was called Minerva, Virtue and Vice; see the table of titles below. The relief does in fact also appear as a portrait of innocence and falsehoodXXVIII.

Only the women’s posture and drapery distinguish them from one another; no other known or easily discernible attributes are found on the side-figures. Minerva alone is clearly “interpreted” by means of such classical attributes as a helmet, an owl, and a short cape wreathed in snakes. One is thus easily led to believe that Thorvaldsen deliberately allowed the side-figures to remain ambiguous, in order to leave room for more than one of the proposed interpretations: a notion that might be supported by the numerous different names that were subsequently attached to the relief. Thorvaldsen, it would seem, did not follow Bulzo’s recommendation that he add relevant attributes to these figures; or rather, he simplified them so much that only their clothing and posture are left for use in identifying them.

These last features, on the other hand, are not unhelpful in this regard. In Cesare Ripa’s Iconografia, for example, Truth is portrayed as a naked woman (as in the expression “the naked truth”), while veiling is used as an indication that something is wholly or partially concealedXXIX, e.g., the truth. Virtue, on the other hand, is not portrayed as a naked woman, according to Ripa, but as an elegant, beautiful woman, often clothed in gold, or as a female warrior. In other words, the women’s nakedness suggests that the reading Truth vs. Lie is the most likely; but it is noteworthy that the motif is, comparatively, so ambiguous, and so devoid of any authoritative interpretation.

Two proposals for the pedestal and the monument’s elevation were sent to Thorvaldsen. One of these—presumably the one chosen—is no longer extant; but drawing D1564 is, with overwhelming likelihood, identical to the draft not chosen of the elevation of Maitland’s monumentXXX. The measurements in drawing D1564 match the 53 pollici (inches, for the length of the bust and pedestal combined) that are specified in Prossalendi’s letter dated 3.5.1817. Similarly, the basic ornamentation of the upper portion of the pedestal and profile in the drawing corresponds to the decoration of the final verison with egg-and-dart ornaments and garlands; see the photograph below of the preserved upper portion of the pedestal, albeit without ram’s heads.

This drawing, D1564, is most likely identical to one of the proposals sent for the elevation of the monument to Maitland; see Naranzi’s letter to Thorvaldsen dated 14.7.1817. The bust does not represent Maitland specifically, but a heroic figure clad in classical armor and warrior dress, as described in the commission; cf. Prossalendi’s letter dated 3.5.1817. In his portrait of Maitland, Thorvaldsen deemphasized the martial element somewhat: he let the Lord High Commissioner appear bareheaded, but kept the armor and classical drapery.

According to Naranzi’s letter dated 16.1.1818, the accepted pedestal had a height of 120 cm and a width and depth of 60.25 × 60.25 cm. Thiele claimsXXXI that Thorvaldsen himself drew a new proposal for the pedestal; but so far no documentation of this has been found. It seems more likely that he simply chose the revised proposal, which Venetian architects had drawn out of dissatisfaction with the proposalsXXXII sent previously. The marble pedestal was finished in Venice, and stood complete no later than 16.1.1818XXXIII.

During the period 1818-1819, Naranzi wrote to Thorvaldsen at least twiceXXXIV to inquire about his progress with the work. Judging by other sources, it appears that the source of the delay was the bronze casting process. Thus Thorvaldsen’s assistant Pietro Tenerani, in his reportXXXV to Thorvaldsen during the latter’s stay in DenmarkXXXVI, wrote that payment for the Maitland monument had not yet arrived, and that the bronze casters Jollage & Hopfgarten accordingly could not be paid either—they were impatient, but would need to be patient somewhat longer, much as Thorvaldsen’s studio had been patient during the delay in casting:

Per altro i fonditori Prusiani sono stanchi d’aspettare piu il pagamento, come lo eravamo noi per il ritardo della fusione.XXXVII

Because there are no extant letters by Thorvaldsen or from his studio pertaining to the Maitland monument, we have no direct evidence that Naranzi’s reminder notices elicited responses from the sculptor. It is clear, however, that a response of some kind was written either by Tenerani or by Hermann Ernst Freund, who managed Thorvaldsen’s studio during his time in Denmark.

The bust’s head was castXXXVIII before Thorvaldsen’s departure for Denmark on 14.7.1819, while the rest of the bust (i.e., the shoulder piece and drapery) and the relief were cast shortly before 2.10.1819XXXIX.

The diaryXL of the Danish priest Frederik SchmidtXLI indicates that a clay model of the relief, at least, must have at least been completed by October 25, 1818, as Schmidt saw the model in Thorvaldsen’s workshop on that day—though it is not known with certainty whether this was a clay or plaster model. It thus cannot be established precisely when the clay model was ready, nor when it was cast in plaster and became what is here referred to as “the original model.” Thiele writes at one pointXLII that Thorvaldsen worked on the models during the year following the summer of 1817; elsewhereXLIII he states that both models were complete by the fall of 1818. Although these assertions cannot be verified with other sources, it is certain that both models were finished by some time before the first casting of the upper part of the bust was complete, viz., prior to Thorvaldsen’s departure for Denmark on 14.7.1819.

The Maitland monument was installed in Zante no later than on 17.12.1820, the planned date of its dedication. This dating is due to Archduke Ludwig Salvator’s book on Zante, op. cit.

Salvator relates that the monument was to be unveiled during the procession for St. Dionysios, patron saint of Zante. When the procession reached the Church of All Saints (Ay Pandes, i.e., Hagioi Pantes), the Te Deum was to be sung, and the unveiling was to take place during the speeches; on this compare Sass, op. cit., p. 423, who also cites Salvator. This plan was met with protests by orthodox circles, however; and when it both rained and hailed the next morning, this was regarded as a miraculous gesture of support to the faithful from above, and the monument’s dedication was postponed.

According to another version of the story, which is not necessarily incompatible with the first, the monument was smeared with something “unnameable”XLIV on the night after its unveiling; the perpetrators were local patriots supporting the Greek war of independence, and who thus were demonstrating their support for unified Greek rule. The latter was not to become a reality until 1864, however; and even when it did, the new constitution specified that Maitland’s monument was to be preserved. This inflamed sentiments once more, and someone wrote anonymously on the monument (here reproduced in French following the articleXLV describing the affair):

On eut soin de moi et me voilà assuré par traité. Sans quoi j’aurais été volé et transformé en marmites.

Though none of this can presently be verified by other sources, there can be no doubt that the Maitland monument was a political football in the intrigues of the day relating to power, autonomy, and democracy. As Sigurd Schultz, former director of Thorvaldsens Museum, laconically and yet encouragingly wrote in his letter to a minister in the Royal Danish Embassy in Athens:

“As far as I understand, Sir Maitland was by no means a beloved governor of Zante. It might be thought that this is the reason why the Greeks are not at all interested in the bust, as we are.”

The monument to Maitland no longer exists in its entirety, let alone in its original location. During World War II, Zante was occupied by Italy, and the bust was taken as spoils; but a warden at the local Byzantine museum succeeded in rescuing the relief, which is found today in Zante’s city hall. The bust on Maitland’s monument was instead replaced by a bust portraying the Italian poet Ugo Foscolo (1778-1827), who was born on Zante.

There are numerous stories in circulation about the bust’s subsequent history, all more or less unverified. According to one variantXLVI, the bust and relief were brought to Italy on Mussolini’s orders, to be melted down; according to anotherXLVII, the warship carrying the bust to Italy was torpedoed and sank; according to a thirdXLVIII, the captain of the (possibly) torpedoed warship survived along with the bust, and succeeded in keeping the bust along with other treasures plundered from the Byzantine Museum. The last source further reports that the captain sold the bust, and that it is still to be found “out there.”

At present, none of these accounts can be verified. A letter dated 17.1.1950XLIX from the Greek government’s press office does confirm that the Italian warship carrying the bust was torpedoed; but no information is provided about the rescue of people or goods. The relief, on the other hand, was definitely rescued. After several years in the Byzantine Museum, it is now found in Zante City HallL.

The original bronze relief mounted on the pedestal to the Maitland monument was rescued from Italian plundering in 1942, and is found today in Zante’s city hall. It was previously held in the Byzantine Museum in Zante CityLI. While the precise measurements of the bronze relief have not here been determined, it is clear that the relief’s shape is more square in the bronze version than in the original model. This is presumably either because the original model’s corners were cut off, or simply immured, during its installation in Thorvaldsens Museum, or because the Zante relief’s sides were lengthened during the bronze casting process in order to prepare it for installation there.

Beyond the bronze relief in Zante’s city hall, the original monument’s only surviving remnant is the uppermost portion of the pedestal. In this photograph, from approximately 1980LII, it is clear that the pedestal was used as a planter. It has not yet been determined where on Zante the pedestal was located at the time of the photograph; nor is it known where it is found today.

Review of the documents has led to a change in the relief’s name. Since its incorporation in the museum, the relief has been titled Minerva, Virtue and Vice; but now, with its original meaning restored, it is called Minerva, Truth and Lie. This does not exclude the possibility that the relief once had both meanings; not to mention that there was at one point, as mentioned above, a suggestion by those behind the commission that two side figures be made to represent Freedom and Slavery instead. The idea of multiple meanings is supported by the multiplicity of names that have been attached to the relief, and which are collated in the table below. Even the function of the relief is unclear: as the table below indicates, it is repeatedly designated a “tombstone” by Johan Bravo.

In his first four-volume biographyLIII of Thorvaldsen and his works, Thiele calls the relief Minerva Exposes Vice, and Takes Innocence Under Her Protection. In his second biographyLIV, Thiele uses a revised title: Minerva Exposes Lie, and Takes Truth Under Her Protection. Thiele evidently revised the title after finding and reading the letter from Bulzo dated 7.4.1818, which he mentions in the biography; he had similarly become aware of the list of drawings of Thorvaldsen’s works. When the relief was registeredLV in Thorvaldsens Museum by Ludvig Müller, it was called Monument to Maitland: Minerva Exposes Vice, presumably based on Thiele 1832 and on Johan Bravo’s estate inventory, on which see the table below.

| Source | Title |

| Dionisio Bulzo’s description apropos of the commission, 7.4.1818 | o la libertà e la schiavitù, o se ella crede meglio la verità e la menzogna. |

| Frederik Schmidt’s description of the relief, 25.10.1818LVI | [...] Minerva who exposes falsity and protects honesty. |

| List of drawings of Thorvaldsen’s works, dated presumably 1844 | Minerva che scuopre la menzogna, e protegge la verità |

| List of drawings of Thorvaldsen’s works, dated presumably no earlier than 1829 | Minerva che protegge la verità e scopre la menzogna |

| Thiele 1832, p. 44 | Minerva Exposes Vice, and Takes Innocence Under Her Protection |

| Thiele II (published in 1851), p. 384 | Minerva Exposes Lie, and Takes Truth Under Her Protection |

| Bravo’s list dated presumably 1839 | Pallade, innocensa e perfidia |

| Bravo’s list dated 3.9.1839 | Minerva, die Unschuld u Falschheit, über Marmor |

| Bravo’s inventory of Thorvaldsen’s estate, dated 24.5.1844 |

Basso Rilievo sepolcrale, Minerva va con la Virtù e Vizio. og Detto: Minerva con la Virtù e Vizio in gesso. |

| Bravo’s inventory of Thorvaldsen’s estate, dated 24.5.1844 |

Basso Rilievo Sepolcrale, Minerva con la Virtù e Vizio. og Detto ― Minerva con la Virtù, e Vizio in gesso. |

| Bravo’s inventory of Thorvaldsen’s estate, dated 24.5.1844 |

Minerva with Virtue and Vice, Tombstone, Bas-relief and Minerva with Virtue and Vice |

| Bravo’s ship’s manifest dated prior to 7.8.1844 | Bas-relief for the Tombstone of Lord Maitland |

| Müller’s inventoryLVII, THM | Minerva Exposes Vice |

| Ludwig Salvator, op. cit., vol. II, 1904, p. 14 | Die Figur stellt die Minerva dar, welche mit ihrem rechten Arm die Tugend umschlingt und mit ihrer Linken einen Schleier auf das Laster wirft, welches gedemüthigt und gebeugt dahinzieht. |

One marble version of the relief is extant, and is found today in the Oldenburg branch of the Lower Saxony State Museums, Landesmuseum für Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte, inv. no. LMO 14.017. It measures 75.5 by 62 cm, and judging by photographs, it is well-carved and of very high quality. While the relief’s provenance is still unknown, it may be identical to the Minerva relief described in Thorvaldsen’s workshop accounts from July 1819 – December 1823, December 1821 – September 1823, and June 1822 – June 1823.

The only extant marble version of the relief, presumably produced in 1822, is found today in the Oldenburg branch of the Lower Saxony State Museums (Niedersächsische Landesmuseen), Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, inv. no. LMO 14.017.

Last updated 13.01.2025

See, e.g., the quotation from Joseph Hume (1777–1855) below.

Defined as the islands Vathy (Ithaca), Cephalonia, Cythera, Corfu, Lefkas, Paxos, and Zante (Zakynthos).

Cf. Thiele II, p. 318.

See Sass’s translation, op. cit., p. 422. The year is given in accordance with the Greek (Julian) calendar, and corresponds to our (Gregorian) 1818.

Cf. Hansard, Great Britain, House of Commons, Hansard’s parliamentary debates, Commons Sitting of Thursday, June 7, 1821, George IV year 2, Column 1129, Second Series, Volume 5. I am grateful to Katie Sambrook, Special Collections Librarian, Foyle Special Collections Library, King’s College London, for drawing my attention to this speech. The rest of Hume’s highly critical remarks can be read here. Hume’s remarks are summarized in Scott, op. cit.

Cf. Frewen, op. cit., p. 209.

Cf. Hansard, Great Britain, House of Commons, Hansard’s parliamentary debates, Commons Sitting of Thursday, June 7, 1821, George IV year 2, Column 1129, Second Series, Volume 5. I am grateful to Katie Sambrook, Special Collections Librarian, Foyle Special Collections Library, King’s College London, for drawing my attention to this speech. The rest of Hume’s highly critical remarks can be read here. Hume’s remarks are summarized in Scott, op. cit.

The bust mentioned here was not, as claimed, by the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova, but was instead the colossal bust by Thorvaldsen. Cf. its original model, A258, which had just been erected in front of the Zante church.

Cf. Sass, op. cit., p. 421, and Frewen, op. cit., pp. 33, 142, 161, 172, 241, 277, 283, 293.

By General Charles Napier (1782–1853), as cited in Frewen, op. cit., pp. 282-283.

A quotation from General Charles Napier (1782–1853); cf. Frewen, op. cit., pp. 282-283.

One may assume that this was Thorvaldsen’s own initiative. Cf. Bulzo’s reply dated 7.4.1818.

Cf. Sass, op. cit., pp. 422-423.

Cf. Municipal Gallery of Corfu.

Cf. Sass, op. cit. pp. 422-423, and Salvator, op. cit., “Speciéller Theil,” pp. 13-14.

Cf. the letter from Prossalendi dated 3.5.1817.

Cf. Ordbog over det danske Sprog and William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D., A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (London, 1875), pp. 359-360.

Cf. Sass, op. cit., p. 418.

Among Thorvaldsen’s portraits, crowns are only found in those of the Indian prince Ghazi-ud-Din Haidar, A280, and Conradin, a historical portrait, A150.

Specifically, on the relation between the drawing and the relief Thorvaldsen was to produce, Naranzi’s letter stated as follows: … eseguito come stà e giace, e senza la benchè minima alterazione … Cf. the letter from Naranzi dated 16.1.1818.

Cf. the letter from Naranzi dated 16.1.1818, which was accompanied by a drawing of the desired relief, and the letter from Bulzo dated 7.4.1818.

Cf. the letter by Naranzi dated 16.1.1818.

Cf. the letter from Bulzo dated 7.4.1818.

See, e.g., Thiele’s editions of Den danske Billedhugger Bertel Thorvaldsen og hans Værker [The Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen and His Works] (Copenhagen, 1831, 1832, 1848, and 1850), and the Related Article on Contemporary Reproductions of Thorvaldsen’s Works.

Cf. the letter from Bulzo dated 7.4.1818.

Cf. Thiele II, p. 384.

Cf. the letter from Bulzo dated 7.4.1818.

Cf. Johan Bravo’s list dated 3.9.1839, in which the relief is designated either item 11—namely, Minerva, die Unschuld u Falschheit, über Marmor—or item 12:

Minerva.

Cf. Ripa, op. cit., p. 671, and J. E. Cirlot, A Dictionary of Symbols (London, 1971), pp. 230 and 359, respectively.

Cf. Sass, op. cit., vol. III, p. 172, note 817, who proposes an identification of this rejected drawing with a specific drawing held by Thorvaldsens Museum. The classification system Sass referred to has since been changed, however, making it impossible to trace her reference directly. But in all likelihood the drawing in question is D1564. Cf. the note Rekonstruktion af Magasin E [Reconstruction of Magasin E], prepared by Marit Ramsing between October 18, 1983 and April 2, 1984, in which the drawing is mentioned on p. 5. This drawing was first listed in the Thorvaldsens Museum catalogue as “Et Gravmæle med en Portrætbuste af en Mand i romersk Krigerdragt foroven (Pen)” [A Tombstone, with a Portrait Bust of a Man in Roman Martial Dress Above (Pen)], cf. Tillæg til Hoved-Katalogen [Appendix to the Main Catalogue], THM, pp. 58-59. The other drawing—the one Thorvaldsen chose, and possibly corrected—was presumably sent back to Naranzi (cf. Sass, op. cit., p. 416), unless it was subsequently lost.

Cf. Thiele II, p. 319.

Cf. the letters from Naranzi dated 14.7.1817, 5.9.1817, and 16.1.1818.

Cf. Naranzi’s letter dated 16.1.1818.

Cf. the letters from Naranzi dated 20.6.1818 and 25.5.1819.

I.e., the letter from Tenerani dated 16.1.1820.

Thorvaldsen traveled to Denmark on 14.7.1819, and returned to Rome on 16.12.1820.

Cf. the letter from Tenerani dated 16.1.1820.

Cf. the letter by P. O. Brøndsted to Thorvaldsen dated 2.10.1819, and the letter from Tenerani dated 16.1.1820.

Cf. P. O. Brøndsted’s letter to Thorvaldsen of the same date.

Cf. Ole Jacobsen og Johanne Brandt-Nielsen (ed.), Provst Frederik Schmidts dagbøger [The Diaries of Provost Frederik Schmidt], vols. 1-2, Copenhagen 1966-69, vol. 2, p. 398.

I.e., the Danish priest Frederik Schmidt.

Cf. Thiele II, p. 319.

Cf. Thiele II, p. 384.

Cf. Sass, op. cit., p. 423, and THM, j.no. 6-21/1946, which contains a clipping of the September 21, 1946 issue of Messager d’Athènes, 21.9.1946. The precise formulation was: les Zantiotes s’empressèrent de frotter la figure de Maitland avec… on devine bien quod.

Cf. Sass, op. cit., p. 423, and THM, j.no. 6-21/1946, which contains a clipping of the September 21, 1946 issue of Messager d’Athènes, 21.9.1946. The precise formulation was: les Zantiotes s’empressèrent de frotter la figure de Maitland avec… on devine bien quod.

Cf. Sass, op. cit., p. 423, as well as THM j.no. 6-21/1946 (which includes a clipping from the September 21, 1946 issue of Messager d’Athènes). In the course of her research, however, Sass discovered that the relief was still located at the Byzantine Museum in Zante; cf. THM j.no. 6-21/1946 and THM j.no. 7II-6/1949. It is housed today in Zante’s city hall; cf. THM j.no. 7II-4/1980.

Cf. Sass, op. cit., p. 423. See also THM j.no. 6-21/1946 and THM j.no. 7II-6/1949.

Cf. THM j.no. 7II-6/1949.

Cf. THM j.no. 7II-6/1949.

Cf. THM j.no. 7II-6/1949, THM j.no. 7II-12/1950, and THM j.no. 7II-4/1980.

Cf. THM j.no. 7II-6/1949, THM j.no. 7II-12/1950, and THM j.no. 7II-4/1980.

Cf. THM j.no. 7II-4/1980.

Cf. Thiele 1832, p. 44.

Cf. Thiele II, p. 384.

Cf. Müller, Fortegnelse over Thorvaldsens værker i Thorvaldsens Museum (Copenhagen, 1848, p. 69, cat. no. A600.

Cf. Ole Jacobsen og Johanne Brandt-Nielsen (ed.), Provst Frederik Schmidts dagbøger [The Diaries of Provost Frederik Schmidt], vols. 1-2, Copenhagen 1966-69, vol. 2, p. 398.

Cf. Müller, Fortegnelse over Thorvaldsens værker i Thorvaldsens Museum (Copenhagen, 1848, p. 69, cat. no. A600.