Wilhelm Schadow, Self-portrait with Bertel Thorvaldsen and Rudolph Schadow, 1815-1816, Berlin, Alte Nationalgallerie, inv. no. A I 325. Photo: Public domain

A considerable distance in space separated the spectator in Copenhagen from the sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen during his forty years in Rome, ending in 1838. During Thorvaldsen’s final Roman decade, this geographical distance was attended by a new dimension of absence, thanks to a discontinuity in the painting of his portrait by young Danish artists.

Limiting its scope to Thorvaldsen’s Roman years, this paper will briefly draw attention to two narratives about Thorvaldsen available to the spectator. It will be suggested that the sculptor played a role as a link between the history and culture of European civilization as a whole and that of Denmark in particular, and that Thorvaldsen’s portraits address this link; but a decade’s discontinuity in portraying Thorvaldsen also played a certain role in the transformation of these kinds of narratives into long-lasting national romantic narratives.

This paper was given at the conference “Another Horizon. Northern Painters in Rome and Naples 1814-1870” in Rome on October 19-20, 2015, by Laila Skjøthaug, Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen.

Portraits are objects that are to be reminiscences of the individual subject. They represent a human being who is not present, but nonetheless do leave an impression on the viewerI. Portraits are deeply concerned with constructing the sitter’s identity and his/her significance in contemporary culture. Portraits of artists, specifically, have a particular focus on artistic self-consciousnessII, and have traditionally been executed for reasons other than commissions or duty.

Thorvaldsen is one of the most frequently portrayedIII sculptors of all time. The numberIV of Thorvaldsen’s portraits can draw attention to the broad international network of painters who socialized with him in Rome, as well as to Thorvaldsen’s own interest in paintings. Thorvaldsen’s hostess during his final years in Denmark, Baroness Christine Stampe, said that she had never met a person who felt so much love for painted artworks as did ThorvaldsenV. Indeed, ever since his earliest pre-Roman years in Copenhagen, Thorvaldsen had socialized with painters rather than with sculptorsVI.

Wilhelm Schadow, Self-portrait with Bertel Thorvaldsen and Rudolph Schadow, 1815-1816, Berlin, Alte Nationalgallerie, inv. no. A I 325. Photo: Public domain

In Wilhelm Schadow’s self-portrait, painted in 1815-1816 and now at the Nationalgallerie Berlin, Thorvaldsen is represented as the central figure, and has put his hand on the painter’s shoulder. The sculptor Rudolph Schadow, meanwhile, shakes hands with his brother, Wilhelm. This painting has long been regarded as emphasizing a link between sculpture and paintingVII.

The spectator can find a number of narratives in the portraits, introducing Thorvaldsen as a sculptor who mediates or serves as a link between European culture and history in general and the Danish culture and history in particular.

C. W. Eckersberg, Bertel Thorvaldsen in the robes of Accademia di San Luca, 1814, Copenhagen, The Royal Academy of Fine Arts, inv. no. KS 38

In C. W. Eckersberg’s portrait, painted in 1814, Thorvaldsen is visible in the official robes of Accademia di San Luca in Rome, of which he was a member since 1808. This academy, founded in 1577, is among the oldest academies in Europe; its roots can be traced to the first statutes written in 1478 for the guild of painters named Compagnia di San Lucca. These robes endow the portrait with the connotation of an artist who is continuing the work of a long Roman tradition.

|

|

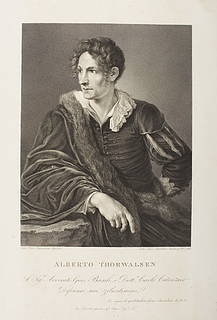

| Vincenzo Camuccini, Portrait of Bertel Thorvaldsen, ca. 1808, private collecton. Engraved by Joseph Saunders, 1823, E6. | Jacob Munch, Portrait of Bertel Thorvaldsen, Oslo, Nasjonalmuseet, inv. no. NG.M.03258. Photo: Nasjonalmuseet, Jacques Lathion. |

The president of Accademia di San Luca, Vincenzo Camuccini, painted a portrait of Thorvaldsen during the year of his membership, 1808. This painting is in a private collection, but in Thorvaldsens Museum we have Joseph Saunders’ engraved reproduction. Camuccini’s portrait, as well as Jacob Munch’s portrait, also stress tradition as an important part of Thorvaldsen’s identity, by representing him wearing Renaissance-style robes.

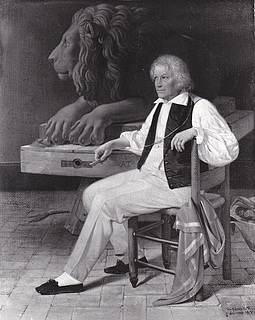

Andreas Koop, Portrait of Bertel Thorvaldsen, 1828, B168.

Another reference to the Renaissance is the window metaphor. In Munch’s portrait, the spectator gets a glimpse through a window of a Roman panorama, including the Colosseum; a similar glimpse of Roman ruins is offered in Andreas Koop’s portrait. In both, Thorvaldsen appears as a sculptor who relates to ancient civilization as it could be viewed through the Renaissance’s gaze.

Recollection of Thorvaldsen’s northern origin is also prompted by the fact that the composition in Heinrich Maria von Hess’ portrait from 1823 in Neue Pinakothek, Munich, can easily be associated with the composition in Albrecht Dürer’s (1471-1528) 1498 self-portrait. In Hess’ portrait, Thorvaldsen gathers his hands and rests his lower right arm on a table in the foreground. A window is seen as background on his left side, and his left upper arm overlaps the corner of the window. This composition is very close to that in Dürer’s self-portrait.

Dürer lived in Nuremberg, and Thorvaldsen was similarly an artist of northern origin. Yet the Roman ruins in Hess’ portrait of Thorvaldsen also emphasize that an important part of Thorvaldsen’s identity had to do with ancient Rome.

A second narrative is found in Thorvaldsen’s early portraits, in which the sculptor is represented more than once wearing recently received medals of honor.

Rudolph Suhrlandt, Portrait of Bertel Thorvaldsen, 1810, B428.

This can be seen in Munch’s and Rudolph Suhrlandt’s portraits from 1810, the year when Thorvaldsen receivedVIII the Danish order of Dannebrog. The Danish order is also seen in the portrait that Eckersberg painted in 1814. Yet Thorvaldsen had more recently, on 6.2.1814IX, been presented with the The Royal Order of the Two Sicilies, cf. N24, from Naples. Eckersberg’s portrait points to Thorvaldsen’s connections with both northern and southern society. But in more general terms, these early portraits introduce a narrative of honor that can make the spectator aware of Thorvaldsen’s growing reputation and importance.

Eckersberg’s portrait also exhibits a strong focus on honor and triumph when depicting Alexander the Great on his triumphal chariot, cf. A503, as background. This is the central scene of Thorvaldsen’s 1812 relief representing the event of Alexander the Great’s (356-323 BC) entry into Babylon. In a letter to J. F. Clemens dated 11.2.1815X, Eckersberg argued that the relief was “also Thorvaldsen’s triumph.” And the relief had indeed received much attention already. But a spectator can also interpret Thorvaldsen as an “Alexander” of the arts, who conquered the enlightened, modern world with his artwork—while Alexander, representing ancient civilization, used military power to conquer his world.

Some portraits juxtapose Thorvaldsen either with Alexander or with Jupiter. Alexander ruled an empire on three continents, while Jupiter was the ruler of another and marvelous mythological world.

Thorvaldsen’s frieze representing Alexander’s triumph, cf. A503, represents a limited moment of triumph within the sculptor’s career. The portraits’ juxtaposing of Thorvaldsen—first with Alexander, and then with Jupiter—extends the narrative, imagining Thorvaldsen as a more lasting “world conqueror.”

|

|

| Ditlev Blunck, Thorvaldsen in his Roman studio, 1837, private collection. | Bertel Thorvaldsen, Jupiter dictates the laws to Cupid, 1831, A391. |

|

|

| Eduard von Heuss, Thorvaldsen in his Roman studio, D1858, detail related to the portrait Heuss painted in 1834, now in Landesmuseum Mainz, inv. no. 27. Reproduced in Mildenberger, 1991, p. 535 | Bertel Thorvaldsen, Cupid, Jupiter, and Juno, 1831, A394. |

Reclining with his left arm resting on the back of the chair, and his left leg set in front of his right, Thorvaldsen’s classical pose in Ditlev Blunck’s painting from 1837 is a paraphrase of Jupiter in Thorvaldsen’s own 1831 relief, in which Jupiter dictates the laws to Cupid. A similar kind of resemblance can be seen between Thorvaldsen’s pose in Eduard von Heuss’ 1834 portrait in Landesmuseum Mainz and Thorvaldsen’s 1831 relief Cupid, Jupiter, and Juno, in which Cupid asks Jupiter and Juno that the rose be crowned queen of the flowers. In Heuss’s drawing in Thorvaldsens Museum, D1858, the focus is on Thorvaldsen’s figure, as can be seen in the Mainz portrait. Thorvaldsen is represented seated in a forward-leaning position, with his bent left leg up on a stool. The left lower arm rests on his knee, supporting the headXI. This position is a paraphrase of Jupiter from Thorvaldsen’s own relief.

From a purely statistical point of view, German painters contributed the largest number of portraits painted during Thorvaldsen’s Roman years until 1838. The list below orders each artist according to his geographical origin, with the latter classified according to the more recent nation-states. It reveals eleven painters with origin in German territory who executed portraits of Thorvaldsen during his Roman years. Some of these contributed more than one painting, whether as further replicas or with another portrait.

One example of these is the painter Ditlev Blunck, from Holstein. Because he was a citizen of that Danish duchy, Blunck is often assigned Danish nationality. Yet the issue is not so simple. Holstein became Prussian territory in 1864; and after the many years he had stayed in Copenhagen, Blunck’s sympathies for independence for Schleswig-Holstein strengthened, causing him to leave Copenhagen permanently in 1841. For this reason, Blunck has been listed in a separate category of mixed Danish/German origin.

|

Portraits of Bertel Thorvaldsen painted in Rome during his Roman years, 1798-1819 and 1820-1838 |

| Artist’s geographical origin | Artist, dating, owner | Replica | Copy | |

| Danish |  |

C.W. Eckersberg, 1814, Copenhagen, Royal Academy of Fine Arts, inv. no. KS 38 | Replica 1832, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum inv. no NM 2491 Replica 1828, Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, inv. no. MIN 0880 |

Copy 1828, head and shoulders, by Christen Købke, Bruun Rasmussen Kunstauktion, 1984, aukt. 465 |

| Portraits of Bertel Thorvaldsen painted during his visit in Copenhagen 1819-20 |

| Artist’s geographical origin | Artist, dating, owner | Replica | Copy | |

| Danish | Portrait of Bertel Thorvaldsen. Miniature |

Christian Horneman, 1820, The Royal Danish Collection, Rosenborg Castle | ||

| Danish |  Miniature Miniature |

Christian Horneman, 1820, B310 | ||

| Danish |  |

C.W. Eckersberg, 1820XII, B454. | Copy by Emil Bærentzen, exhibited 1827; by Carl Løffler, 1828; by H. Matthison-Hansen, ca. 1827. Present location unknown |

| Portraits of Bertel Thorvaldsen painted during his roman years 1798-1838 |

| Artist’s geographical origin | Artist, dating, owner | Replica | Copy | |

| Danish/ Norwegian |  |

Jacob Munch, 1810, Oslo, Nasjonalmuseet, inv. no. NG.M. 03258. Photo: Nasjonalmuseet/Jaques Lationon | Replica 1815 at Hillerød, Frederiksborg Castle, inv. no. A2882. Replica in grissaille at Roskilde Museum |

|

| Danish/ German |  |

Ditlev Blunck, 1834, Kunsthalle zu Kiel, inv. no. 734. | ||

| Danish/ German |  |

Ditlev Blunck, 1837, private collection | ||

| German |  |

Rudolph Suhrlandt, 1810, B428. | Replica, B422. Replica (?) at Christie’s New York, April 3, 2002. Replica(?), reduced size, Rome, private collection  |

|

| German |  |

Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein, 1815, B425 | Copy, head and shoulders, by Friedrich Wasmann, 1833, Hamburger Kunsthalle, inv. no. 1363 | |

| German |  |

Adolf Senff, 1817-18, Moritzburg, Kunstmuseum des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt, Halle, inv. no. MOI 0184. | ||

| German |  |

Karl Begas, 1823, Alte Pinakothek, Berlin, inv.no. A I 16. Foto: ©Nationalgalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin – Preuβischer Kulturbesitz. |  Karl Begas, 1823, replica in St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum, inv. no. 5761. Photo: public domain. Replica in Poznan, Galleri Raczynski |

Copy by Andreas Koop, 1828, B168  Copy by Adolf Senff, formerly in Hannover, Landesmuseum. Copy (?) at Hillerød, Frederiksborg Castle |

| German |  |

Heinrich Maria von Hess, 1823, Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen – Neue Pinakothek, inv. no. WAF 348 | ||

| German |  |

Adolf Senff, ca. 1823, Moritzburg, Kunstmuseum des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt, Halle, inv. no. MOI 1563 | ||

| German |  |

Dietrich Wilhelm Lindau, ca. 1827, B424 | ||

| German | Photo not available. Reproduced in the catalogue from Grisebach Auctions, p. 24 |

Eduard Magnus, ca. 1828, at Berlin, Villa Grisebach Auctions, July 3, 2015 |  Eduard Magnus, ca. 1830, B132. |

Copy by Andreas Koop, received by Joseph Hambro before 28.4.1831. Present location unknown. |

| German |  |

Ehregott Grünler, 1829, previously in Sweden and in Canada, private collections | ||

| German | Ehregott Grünler: Bertel Thorvaldsen |

Ehregott Grünler, 1830, Weimar, Klassik Stiftung, inv. no. KGe/00252 | ||

| German |  Miniature |

August Grahl, 1830. Present location unknown. | Replica in the Staatliche Gemäldegalerie, Dresden | |

| German |  |

Bernhard von Guérard, 1831, Museo Capidomente, Naples. |  Replica 1834, B447 |

|

| German |  |

Heinrich Maria von Hess, 1834 (burned June 6, 1931, at the Münchener Glaspalast) Reproduced in Thorvaldsens Museum, inv. no. E2061 |

||

| German |  |

Eduard von Heuss, 1834, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, deposit in Thorvaldsens Museum, Dep.2 | ||

| German |  |

Eduard von Heuss, D1858. Detail related to Heuss’ portrait, 1834, in the Landesmuseum Mainz, inv. no. 27. reproduced in Mildenberger, 1991, p. 535 | ||

| Italian |  |

Vincenzo Camuccini, 1808, private collection. Reproduced by Joseph Saunders, E6 |  Copy by Andreas Koop, private collection. A number of copies; a well-known one is in Rome: Luisa Bersani, Accademia di San Luca, inv. no. 0186. |

|

| Italian | Giulio Cesare Poggi: Bertel Thorvaldsen |

Giulio Cesare Poggi, 1833, Milano, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, inv. no. GAM 7080 | ||

| Italian | Giulio Cesare Poggi: Bertel Thorvaldsen |

Giulio Cesare Poggi, 1832, Milano, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, inv. no. GAM 2184 | ||

| Italian |  |

Fioriano Pietrocola, c 1835, B426 | ||

| American |  |

William West, 1820s, B449 | ||

| American |  |

James Bowman, 1828, present location unknown | ||

| American |  |

Rembrandt Peale, 1829, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia | ||

| American | Photo not available | Samuel B. Morse, 1831, The Royal Family, Denmark | ||

| American |  |

Samuel Bell Waugh, 1838, USA, McGuigan CollectionXIII. Sketch | ||

| American | Photo not available | Samuel Bell Waugh, (1838), Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts | ||

| American |  |

Attributed to Samuel Bell Waugh. Present location unknown | ||

| British and English |  |

Sir Thomas Lawrence or Thomas Wright, ca. 1830. Private collection | ||

| British and English | Photo not available. Reproduced in Kanzenbach, A., op. cit., 2007, p. 27, abb. 3 |

John Philip Davis, 1830s (?), At Sotheby’s Billinghurst, February 28, 2001. At Christie’s, London, April 30, 2014 | ||

| British and English |  |

Edward Matthew Ward, 1838 (?), Private collection | ||

| Russian |  |

Orest Kriprenskij, 1833XIV, Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. | ||

| French |  |

Horace Vernet, 1833, B95 | Replica in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; possibly executed before Thorvaldsen left Rome in 1838 |

The number of portraits by German painters is much higher than those by painters with Danish, Italian, or any other origin during the same period of time.

The contribution by Danish painters was somehow limited until 1838. Koop painted his portrait in Rome in 1828, as did Eckersberg in 1814; though the replicas Eckersberg painted of his 1814 portrait were made when he was back in Copenhagen. Eckersberg’s second portrait in 1820, and Christian Hornemann’s portraits, are all related to Thorvaldsen’s visit in Copenhagen.

The number of portraits available in Copenhagen was still low, however, and during his 40 years in Rome Thorvaldsen visited Copenhagen only once in 1819-1820. Nonetheless, even a spectator situated in Copenhagen would have been able to see the three portraits that follow and familiarize himself/herself with the narratives that I have pointed out.

Koop’s 1828 portrait was executed in Rome and exhibited at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen’s 1828 exhibit, while Koop remained in Rome. This portrait would later become part of the Thorvaldsens Museum collections.

As of 1814, Eckersberg’s portrait had become part of the Royal Academy’s collections. Immediately after Eckersberg finished the painting, he sent it to them as a gift. It was exhibited at the academy in the following year, and he would execute a couple of replicas some years later.

Munch’s 1810 portrait was shown to the professors at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen in 1813, and was included in his exhibition at Det harmoniske SelskabXV the following year, before he left for Oslo.

Thorvaldsen’s role nonetheless remained vague for a decade, inasmuch as the young Danish painters who visited Rome in the 1830s left behind what I will call narrative “blanks” in terms of interpretation of Thorvaldsen’s role as sculptor. They did not paint new portraits. Without any reference to these artists’ opinions or intentions, these “blanks” can be said to have played a part, during this decade, in opening up a new playground for other views of how to construct Thorvaldsen’s artistic identity, as well as for other potential—though not necessarily predictable—interpretations and narrations.

Thorvaldsen’s early portraits had celebrated the sculptor’s early success, and were followed by more informal portraits during his Roman years. He was often represented wearing his working coat, as in Koop’s portrait.

C. A. Jensen, Portrait of Bertel Thorvaldsen, 1839, National Historical Museum Frederiksborg Castle, Hillerød, inv. no. A80.

Then priorities changed. Shortly after Thorvaldsen’s return to Copenhagen, on September 17, 1838, C. A. Jensen painted his portrait in 1839. Thorvaldsen is depicted in royal scale and in a royal pose, dressed in the robes of the French academy in Rome, carrying a number of medals of honor, and attended by his bozzetto for Nemesis, A19a, modeled for Christiansborg Palace in Copenhagen. The Danish royal family had influence on this representation. As in every European country of the time, it was convenient for official Denmark to have towering figures with origins among the common people who could be held up as exemplary models. Jensen’s portrait is nearly life-size, and sets Thorvaldsen in a national-romantic aura from which he until this day has hardly returned.

The suggestion made in this paper is that the narrative “blank” and discontinuity of the 1830’s, too, played an important role in paving the way for a change in priorities when constructing Thorvaldsen’s identity and role as sculptor.

Many thanks to Stefano Grandesso, Mary McGuigan, Tabea Schindler, and Nicholas Stanley-Price for providing new information.

I also wish to thank David Possen for his brilliant editorial assistance.

Sidst opdateret 24.06.2019

Cf. Gördüren, P., op. cit., 2004, p. 10.

Cf. Mildenberger, H., op. cit., p. 193: underlines how the growing, romantic cult of the artist as genius, with the importance that was also ascribed to the artist’s studio.

Cf. the related article Portrætter af Thorvaldsen af Ernst Jonas Bencard.

Kanzenbach, A., op. cit., 2007 p. 16, refers to Thieme-Becker, 1907ff, vol. XXXIII, where more than 200 painted and drawn portraits of Thorvaldsen are listed.

Cf. Stampe, R. (ed.), op. cit., 1912, p. 239; Henschen, E., op. cit., 2003, p. 100.

Cf. Henschen, op. cit., p. 94.

Cf. Mildenberger, H., op. cit., 1991, p. 521.

Cf. 28.1.1810.

Cf. letter dated 6.2.1814.

Cf. 11.2.1815.

The Jupiter-resembling pose is combined with the supporting finger in Thorvaldsen’s statue Maria Fjodorovna Barjatinskaja, marble executed 1819-25. Thorvaldsens Museum inv.nos. A171 and A172.

Cf. Stig Miss, op. cit., 1997, p. 181-182: Eckersberg’s portrait from 1820 was a result of Thorvaldsen’s visit in Copenhagen, and became part of a lottery among the members of the Art Society in January 1838. The painting was won by someone named “Rev. Riis”. After that date it remained in various private collections until 1994, when it entered the collections at Thorvaldsens Museum as inv.no. B454.

B419 was bequeathed to the museum 1855.

With many thanks to Mary McGuigan for sharing the research she has made for this portrait. The painting does not carry any date, but according to McGuigan’s research, it was probably began late 1837 and completed some time during the first months of 1838.

B441 by Apollinarij Horawski, was executed 1852.

Cf. Jacob Munch’s biography.