From Genii to Angels and Back

- Kira Kofoed, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2016

- Translation by David Possen

This article describes the confusion of motifs and titles surrounding a pair of reliefs by Thorvaldsen depicting winged young boys singing and playing music; cf. the original models A586 and A588.

The reliefs’ little boys have been variously regarded as Christian angels and secular genii. Scrutiny of the available sources reveals that while the reliefs seem to have originally been intended to depict the genii of music, confusion about their nature has been rife since their completion. Despite the persistence of divergent interpretations of their motif, the reliefs were nonetheless integrated with ease into Christian and church contexts.

Genii of music or little boy angels?

From the moment Thorvaldsens Museum opened its doors in 1848 and published its first register of artworks, two reliefs with identical measurements and closely related motifs have made their appearance here under a variety of titles, all versions of Angels Singing and Angels Playing Music (A586 (fig. 1) and A588 (fig. 2), respectively). These two reliefs clearly form a pair, and were formerly presumed to be associated with a commission for a communion table in the Cathedral of Novara, Italy.

|

|

| Fig. 1. The Genii of Music Singing, A586, original model (previously called Angels Singing). | Fig. 2. The Genii of Music Playing, A588, original model (previously called Angels Playing Music). |

However, the reliefs’ nearly square measurements do not fit the rectangular measurements specified in the Novara commission, and in any case there were two other reliefs produced for that commission; cf. A590 and A591. What is more, contemporary sources reveal that, rather than angels, these reliefs in fact depict genii (i.e., guardian spirits), which are far more common motifs in Thorvaldsen’s art than angels.

Genii of music: a newly discovered mention of the reliefs

In a biography of the first known owner of the pair of reliefs, the British nobleman and politician Charles Bowyer Adderley, we find specific mention of the two reliefs and their motif. The reliefs were acquired in marble during Adderley’s visit to Rome in 1835-1836, and were subsequently installed at his manor house, Hams Hall, which once stood near Birmingham. In Adderley’s posthumous biography, which is based on his diaries and notes and to that extent must be regarded as reliable, the reliefs are called Singing Genii and Playing Genii, respectively, indicating clearly that the reliefs were passed on to Adderley as representations of genii.

It is primarily thanks to the recent rediscovery of Thorvaldsen’s decorative sculpture at Hams Hall that these reliefs can now be reinterpreted in their original context. On first inspection, Thorvaldsens Museum’s collections did not seem to contain any reliefs that fit these titles unambiguously; it was only after photographs of the Hams Hall reliefs were found that it became clear that these were replicas of the reliefs known in the museum as Angels Playing Music and Angels Singing.

Searches in the Archive for “genii,” “putti,” “angeli” [angels], “musica” [music], etc., led to the discovery of the final crucial contemporary source: a mention in Thorvaldsen’s workshop accounts of two reliefs with the “tré geni della musica” [three genii of music].

These sources also revealed that the relief had been described both as Boys Singing and Boys Playing Music, or in conjunction as Little Boys Playing Music and Singing. It is further possible that these are the reliefs described simply as Tré putti [three putti], and presumably as early as 1834 as 3 singende Engel [three singing angels], one year before they are referred to as genii in the workshop accounts. A complete list of these mentions is provided in the table at the end of this article.

The references to both “boys” and “little boys” correspond to the general category “putti,” literally meaning “little man” or “boy”—a category that covers associations to angels, genii, and more secular spirits of love such as cupids, as well as the so-called spiritelli, a kind of airborne spirit that affects the human body and emotional life.

In general, with the exception of one isolated mention of them as “angels” in 1834, the two reliefs seem to have been included, in Thorvaldsen’s own lifetime, within the sculptor’s larger set of motifs depicting the genii of various art forms and concepts. Accordingly, the reliefs have now been retitled The Genii of Music, with the specification that they are playing music or singing, respectively.

|

|

| Fig. 3. The Genii of Music Singing, A585, marble (previously called Angels Singing). | Fig. 4. The Genii of Music Playing, A587, marble (previously called Angels Playing Music). |

The reliefs at Thorvaldsens Museum: internal confusion

Despite the above, Ludvig Müller, the first curator of Thorvaldsens Museum and author if its first official register of Thorvaldsen’s works, included the two reliefs in his list of “Christian reliefs” by Thorvaldsen, under the titles Three Angels Singing Praises and Three Angels Playing Music. Müller’s choice of titles is presumably based on Just Mathias Thiele’s first biography of Thorvaldsen and list of his works, published in 1848, which referred to the reliefs as Three Angels Playing Music and Three Angels Singing, respectively. Müller may also have been influenced by correspondence to and from the Committee for the Establishment of Thorvaldsens Museum, as well as by the titles used on the plaster cast company Antonettis Enke’s list of their selection of Thorvaldsen reproductions. The addition of Praises in the title is probably Müller’s own addition, meant to sacralize the motif still further. Müller’s efforts helped to build a consensus, lasting from the Museum’s opening until quite recently, to the effect that these reliefs portrayed angels.

Nevertheless, there are exceptions. A poem dated June 1872 by the British author and poet Edmund Gosse reveals that at least one of the two reliefs was then called Playing Genii. Because this poem was apparently composed in front of the work itself at Thorvaldsens Museum, it may be inferred that the title was derived from a source at the Museum. The Museum’s English-language visitor’s catalogue published in 1871—i.e., the year prior to the publication of Gosse’s poem—turns out to refer to the marble versions of the reliefs as Playing Genii, A587, and Singing Genii, A585, respectively. By contrast, the original models in plaster appear under the titles Angels Playing Music, A588, and Angels Singing, A586.

Though evidently a quite concrete matter, this confusion of motifs went long undetected—even after the works were integrated into the Museum’s collections. A review of all published Danish visitor’s catalogues reveals that the reliefs continued to bear correspondingly different titles in all of the catalogues printed between 1848 and 1947. The marble reliefs (figs. 3 and 4), which were installed in Room II on the ground floor, were entitled—despite Müller and Thiele—Playing Genii and Singing Genii, respectively; while the original models (figs. 1 and 2), installed in the North Corridor on the upper floor, retained the titles Angels Singing and Angels Playing Music. This inconsistency was not officially corrected until 1951. Starting in the museum catalogue published that year, all of the putti were called “angels,” without any reason given. This practice continued without interruption until 2015, when evidence from the decorative sculptures at Hams Hall, along with the present investigation of the contemporary sources, made it clear that it was most accurate to regard these little winged boys as genii.

Additional evidence for the “genii” interpretation

Increased sacralization and prudery

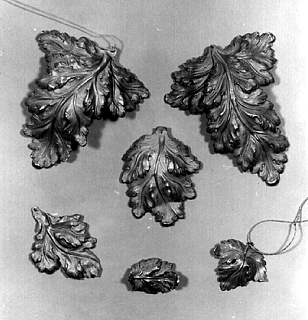

As has already been noted, the fact that the reliefs’ motif has long been set in a Christian, ecclesiastical context is due to some degree to Thiele’s impression that they originated in the commission for the Cathedral of Novara. It is also possible that their sacralization reflects the rise in prudery toward the end of the first half of the nineteenth century. This prudery found expression, for example, in the use of a metal fig leaf to cover up the penis of a plaster cast of Cupid Triumphant, A22, (fig. 5), prior to its exhibition in 1826 at the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen. Similarly, a table decoration consisting of bronze miniatures of selected Thorvaldsen statues was outfitted—apparently by the Danish royal family itself—with removable fig leaves (fig. 6) designed to conceal the male figures’ unmentionables.

|

|

| Fig. 5. Cupid Triumphant, A22, which was outfitted with fig leaves to cover Cupid’s genitals for an 1826 exhibition at the Academy of Fine Arts. | Fig. 6. Fig leaves for covering the genitals on the six male figures in Christian 8’s table decoration, The Royal Danish Collection, Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen. |

The most telling comparative case for the two reliefs of small singing or playing genii is without a doubt the very young version of “Cupid Triumphant,” mentioned above, which is not—unlike the other male figures in the table decoration—depicted as a full-grown man, but rather is still mostly a child, who might accordingly have been presumed to be sexually harmless. The same holds, indeed to a still greater degree, of the reliefs’ small singing and playing genii, who are portrayed as little boys of no more than four years. The small figures’ genitalia are freely visible, except for the middle boy, whose privates are partly concealed by his mandolin.

By contrast, in the reliefs produced for the Communion table in the Cathedral of Novara (figs. 7 and 8), all of the little angels’ privates are decorously concealed by the swung garland, or—in one case—blocked entirely by the rotation of an angels’ lower body into profile. This difference between nakedness and concealment could well reflect a conceptual distinction between secular genii and churchly angels. While this difference is by no means an immutable law in Thorvaldsen’s art, it is generally true that his angels appear more fully clothed than do his genii, who are most commonly portrayed as completely naked.

Figs. 7 and 8. The two reliefs entitled Hovering Angels, A590 and A591, respectively, produced for the high altar in the Basilica di S. Gaudenzio, Novara. The privates of two of the putti are decorously concealed by the garland; those of the third, by the fact that the putto’s lower body is in profile.

Applied attributes: Christian or classical?

Another parameter of evident interest here is the use of attributes in the reliefs. At a later stage, Thorvaldsen produced another relief portraying a single genius of music: The Genius of Music, A535 (fig. 8). Here the aulos (double flute) of the satyr Marsyas is used as an attribute; while The Genius of Poetry, A532, (fig. 9), from the same series of reliefs, uses Apollo’s lyre as an attribute. These attributes reflect Dionysian and Apollonian principles, respectively: wild and untamed nature, on the one hand, and moderate nature disciplined by reason, on the other.

|

|

| Fig. 8. The Genius of Music, A535. | Fig. 9. The Genius of Poetry, A532. |

Whereas this series of reliefs references the attributes of classical antiquity, the two corresponding reliefs of the genii of music make use of more modern instruments, namely, the harp, the mandolin or zither, and the flute.

The Christian patron saint of music is St. Cecilia, who is most commonly accompanied by an organ as her attribute, as well as, at times, by broken musical instruments used for secular music to reflect her rejection of worldly music in favor of that of the heavenly choirs. Had Thorvaldsen followed that strict line, there would be no doubt that these reliefs depict genii rather than angels, inasmuch as the figures play merrily on earthly musical instruments. It is clear, however, that Thorvaldsen did not adopt such strict distinctions; certainly he did not do so ten years later, when he produced the relief Christmas Joy in Heaven, A589 (fig. 10). This relief displays an angel playing the harp, along with seven putti making merrily music on a horn, a bugle, cymbals, a flute, a tambourine, a triangle, and a violin.

Fig. 10. Christmas Joy in Heaven, A589.

For Thorvaldsen, then, there is some slippage in the gap between heavenly and earthly music, inasmuch has he does not forbid his angels to play earthly musical instruments. According to the bronze caster Jørgen Dalhoff, Thorvaldsen once declared that he did not believe that angels’ singing (and their music?) was too spiritual to be depicted in art.

Conclusion

Although the reliefs of singing and playing genii do not include unambiguously classical musical instruments, which can leave the impression that they occupy a middle ground between the classical and Christian spheres; and although the descriptions of these reliefs were quite varied from the start—it seems nonetheless quite clear that the strongest interpretation of these figures, one dating back to Thorvaldsen’s own contemporaries, is as the genii of music.

It is a matter for speculation, meanwhile, whether the reliefs’ frictionless passage from one interpretation to the other was intended by Thorvaldsen. Nevertheless, it is certainly telling that, for a period of 99 years, the reliefs officially—albeit unbeknownst to the Museum’s authorities—went by two different names in their respective marble and plaster incarnations.

List of the reliefs’ varied mentions

| Source | Mention |

| 8.3. – 26.7.1834 | 3 singende Engel [3 singing angels] |

| 1835 (item 12) | i due B.i R.i delli Geni della Musica [the two bas-reliefs of the genii of music] |

| 21.3.1835 | delli tré Geni della Musica [of the three genii of music] |

| 21.3.1835 (unknown whether this refers to the same relief as above) | B[ass]o R[iliev]o delli Tré putti [bas-relief of the three putti] |

| 9.5.1835 (unknown whether this refers to the same relief as above) | al B[ass]o R[iliev]o delli tré putti [on the bas-relief of the three putti] |

| 1835-1836, cf. no earlier than 1878, no later than 1905 | Singing Genii … Playing Genii |

| 1836 | Butti che sonone … Butti che cantano [putti playing music … putti singing] |

| 1837 | Kleine Knaben welche spielen und singen; Basrelief [little boys who are playing music and singing; bas-relief] |

| 19.11.1838 | Smaadrenge, som spille og synge [little boys who are playing music and singing] |

| 7.4.1840 | Syngende Drenge … Spillende Drenge [boys singing … playing boys] |

| 7.4.1840 | Syngende Drenge … Spillende Drenge [boys singing … boys playing music] |

| 11.4.1840 | Syngende Drenge … Spillende Drenge [boys singing … boys playing music] |

| 24.5.1844 (unknown whether this refers to the same relief as above) | [multiple unspecified mentions of the reliefs including:] engle [angels] |

| Ca. 1.4.1845 | de syngende og spillende Genier [the singing and playing genii] |

| August 1846 (nos. 14 and 15) | Tre syngende Engle … Tre spillende Engle [three angels singing … three angels playing music] |

| Thiele 1848, pp. 99-100 | Tre spillende Engle … Tre syngende Engle [three angels playing music … three angels singing] |

| April 1850 | Tre syngende Engle … Tre spillende Engle [three angels singing … three angels playing music] |

| Müller 1848, op. cit. | Tre lovsyngende engle … Tre spillende engle [three angels singing praises … three angels playing music] |

| Thiele IV, p. 264 (1856) | Tre spillende Engle … Tre syngende Engle [three angels playing music … three angels singing] |

| THM, Haandkatalog, op. cit., 1848-1947 | Tre spillende Engle … Tre syngende Engle [three angels playing music … three angels singing] AND Spillende genier [playing genii] and Syngende genier [singing genii] |

| THM, Haandkatalog, op. cit., 1951-1975 | Tre spillende Engle … Tre syngende Engle [three angels playing music … three angels singing] |

| THM, Arkkatalog and Online Catalogue 1975-2015 | Tre spillende Engle … Tre syngende Engle [three angels playing music … three angels singing] |

References

- A Guide to Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen 1871, p. 7 and p. 18-19.

- William S. Childe-Pemberton: Life of Lord Norton (Right Hon. Sir Charles Adderley, K.C.M.G., M.P.) 1814 – 1905: Statesman & Philanthropist, London 1909.

- N. Dalhoff (ed.): Jørgen Balthasar Dalhoff: Et Liv i Arbejde, vols. 1-2, Copenhagen 1915-16.

- Charles Dempsey: Inventing the Renaissance Putto, Chapel Hill & London 2001.

- Nanna Kronberg Frederiksen: Christian 8’s Table Decoration, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk 2014.

- Edmund Gosse: On viol and flute, London 1873, p. 134-136.

- James Hall: Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, London 1984.

- Kira Kofoed: On Genii and Angels in Thorvaldsen’s Art, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/en, 2016.

- Kira Kofoed: Thorvaldsen’s Works at Hams Hall, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/en, 2015.

- Ludvig Müller: Thorvaldens Museum. Tredie Afdeling. Oldsager. Første og andet Afsnit, Copenhagen 1847, p. 112, cat. no. 114.

- Ludvig Müller: Thorvaldens Museum. Første Afdeling. Thorvaldsens Værker., Copenhagen 1848, p. 68, cat. no. 585-588.

- Thiele 1848, p. 99-100.

- Thiele III, p. 489-490 (1854).

- Thiele IV, p. 264 (1856).

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1848.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1849.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1851.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1852.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1856.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1858.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1861.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1866.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1871.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1877.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1881.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1886.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1895.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1898.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1902.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1910.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1916.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1920.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog for de Besøgende, Copenhagen 1921.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog, Copenhagen 1922.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog, Copenhagen 1923.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog, Copenhagen 1925.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog, Copenhagen 1927.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog, Copenhagen 1930.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog, Copenhagen 1932.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog, Copenhagen 1947.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog 1947. Med Rettelser (available in the Thorvaldsens Museum library).

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog, Copenhagen 1951.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Haandkatalog, Copenhagen 1959.

- Thorvaldsens Museum. Katalog, Copenhagen 1975.

Works referred to

Last updated 27.02.2026