Whatever Became of Sophie?

- Karen Jelved, Andrew D. Jackson, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2021

When she was young, Sophie Probsthayn (1773?-1843) knew Thorvaldsen. She was later engaged to H.C. Ørsted but terminated the engagement for unknown reasons. In 1820 she found herself in serious economic problems and asked Thorvaldsen for a loan. It would appear that Thorvaldsen refused. She remained unmarried and died in poverty.

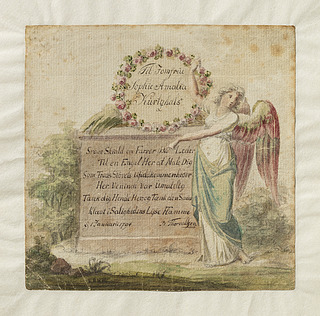

To Miss Sophie Propsthayn

As the stream winds among the flowers

So may your life find joy complete

No hidden thorns should spoil your hours

Where’er you set your dainty feet

Jan. 1st 1795 B Thorvaldsen

This text appears as an inscription on the watercolour C821 as part of its motif. The drawing shows a barefoot young woman in an empire gown making an offering of flowers at a burning altar. To her right, a naked putto is bringing her flowers carried in a basket on its head. In the background there are various trees cypresses. In the left foreground are small flowering plants that are reflected in a stream that winds its way into the background. The above text is written on the altar itself. In short, there is almost literal agreement between the motif of the drawing and the text of the poem.

New Year’s card for Sophie Probsthayn, C821, 1.1.1795.

On January 1, 1795, Thorvaldsen sent this little poem to Sophie Probsthayn as a New Year’s greeting. Who was this Sophie, why did Thorvaldsen send this greeting, and what became of her? Fortunately, there are a number of sources that make it possible to shed some light on Sophie and her life.

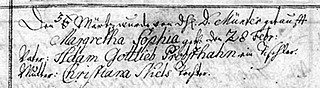

According to the parish register of St Petri Church, Margretha Sophia was born to Adam Gottlieb Probsthahn and Christiana Niels Tochter [Nielsdatter] on February 28, 1773 and baptised one week later on March 5. Her next appearance is in the census of 1787, where she is described as the ten-year-old Sophie Propstein, daughter of the cabinetmaker Adam Gottlieb Propstein, aged 53, and the nine year younger Christiana Nielsdatter, residing at Vestervold 272. The census also mentions her brother Carl David Probsthayn (1770-1818), who was 17 years old at the time.

There are evident problems in determining Sophie’s age. There are similar discrepancies in subsequent census records. In 1834 she is said to be 58, and in 1840 she is said to be 66. Thus, the available records suggest that she was born between 1773 and 1777. We regard the entries in the St Petri parish register as the most reliable. The church record of the baptism of Carl in July 1770 is consistent with his age as stated in the 1787 census. We note that two earlier children of this marriage, Carl Daniel and Carolina Charlotta, died in 1769.

The parish record of Sophie’s birth and baptism (top) and the entry for the Probsthayn family from the census of 1787.

Sophie knew Thorvaldsen through her brother Carl. He and Thorvaldsen became friends during their years together at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, where Carl was a student of Nicolai Abildgaard, who was also Thorvaldsense mentor. In the 1790s, they joined with fellow students Heinrich Grosch and C.D. Fritzsch to form a “drawing club” in Grønnegade with the aim of preparing themselves for the various competitions of the Academy. Neither Grosch nor Fritzsch was successful in these competitions. Thorvaldsen was awarded the large Gold Medal in 1793 for his relief entitled “Peter and John Healing a Lame Man” (A830). Three years later, Carl won the large Gold Medal for his historical painting entitled “Elijah Raises the Son of the Widow of Zarephath”. Like Thorvaldsen, Carl was also a member of Borups Selskab, a private theatre club formed by Knud Lyne Rahbek in 1780. Theatrical performances by and for its members were a primary activity of the club. In the 1790s it also functioned as a discussion club for political radicals who eagerly espoused the notions of freedom of the French revolution.

Carl David Probsthayn: “Elijah Raises the Son of the Widow of Zarephath” (1796).

Photograph: Frida Gregersen, Owner: The Council of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts.

It is possible that Thorvaldsen’s decision to send New Year’s greetings to Sophie Probsthayn was simply motivated by his friendship with Carl. In this regard, it is interesting to note that Thorvaldsen had sent a strikingly similar greeting to Sophie Amalie Kurtzhals precisely one year earlier. It is unclear who composed the poem sent to Sophie Probsthayn, but the verse sent to Sophie Kurtzhals is the fourth stanza of Jens Baggesen’s poem “The Revelation”, written in May 1786. In a letter sent to Thorvaldsen in Rome, Sophie Amalie is described as his “old girlfriend”. It is not known if Sophie Probsthayn was also an “old girlfriend”.

Our next encounter with Sophie is in the Copenhagen census of 1801. She is listed d as residing in the Lion Pharmacy at the corner of Amager Torv and Hyskenstræde, which was owned by Johan Georg Ludvig Manthey (1769-1842). She is said to be 25 years old and is given the title of “housekeeper”. Sophie’s duties included the supervision of one male servant and two older female servants who took care of the washing, ironing and cleaning. She was responsible for the daily housekeeping, kept the household accounts, and prepared meals for the 14 family members and pharmacy employees who lived at The Lion. According to the census, one member of the household was “Hans Chr. Ørsted, unmarried, doctor, 24 years old”.

Manthey had assumed the ownership of the pharmacy in 1795 through his marriage to Augusta Günter, who was the daughter of the previous pharmacist, Christoff Günter. According to the St Petri register, Augusta’s mother, Sophie Charlotte Günter née Hauber (1733-87), was the godmother of Sophie’s dead brother, Carl Daniel Probsthayn (baptised July 11, 1767, died May 24, 1769). There was thus a personal connection between the two families. In the spring of 1800, Manthey embarked on an extended foreign journey with the aim of studying the manufacture of porcelain. This topic was of particular interest to him since he had been appointed Director of the Royal Porcelain Manufactory in 1796. In his absence the 24-year-old Hans Christian Ørsted moved into the pharmacy as the acting leader of the pharmacy. Business was good, but even more interesting things were happening in private. After having heard from his wife about new developments on the home front, Manthey wrote to Ørsted, “Cupid has entwined you and the Miss P. with an indissoluble bond” .

A New Year’s greeting to Sophie Amalie Kurtzhals, CX11, 1.1.1794.

With Manthey’s blessings and active encouragement, Sophie and Hans Christian became engaged before he began his first long foreign journey that lasted from August 1801 until January 1804 and brought him to Germany, France, Belgium and Holland. Until October 1803 all of Ørsted’s travel letters to family and friends were sent to Sophie together with more personal letters to her, which have since been lost. In letters to Manthey Ørsted repeatedly expressed his concern about the length of his journey and thus of the resulting postponement of their marriage. E.g. “Finally: dare I keep Sophie so long with empty promises to come home? She can quite rightly demand that I should turn all my thoughts to establishing a home.” Ørsted met Sophie’s brother Carl in Freiburg in June 1802, and it is not unreasonable to believe that the length of Ørsted’s journey was discussed.

All the while, Sophie waited for her fiancé, who continued to postpone his return. Unfortunately, her coming in-laws were not particularly accommodating. She was invited to participate in family events such as the marriage of Anders Sandøe to his Sophie (Oehlenschläger). One of the female guests described Sophie Probsthayn in terms that could not be misunderstood: “She is an absolute brute.” Georg Jacob Bull (1785-1854), a Norwegian student of law who was engaged to be married to Tine, sister of the Ørsted brothers, wrote to his fiancée: “Do you remember the first days of our relationship when you got angry because I said you beat me as hard as Sophie Probsthein? I do not understand how I could compare your sweet hands with the bony paws of that ass.”

Whichever reason weighed most heavily, Sophie terminated her engagement to Hans Christian at some point in the summer of 1803 — apparently without informing him directly. In a letter to Manthey he wrote, “I shall very soon send you my itinerary. I am not sending it today because I have not had the peace of mind needed to write a draft of it because of a letter that my brother has written about S.P. You must surely know its contents and will hear my response from him. I have nothing to add to what I have said there. I have now been awakened most violently from a contentment, from which various hints, which I only understand now, should already have awakened me”. We know nothing regarding Manthey’s reaction to the termination of Sophie’s engagement or how long Sophie remained at the Lion Pharmacy. We do know that Johan Manthey sold the pharmacy to Max Boye in 1805.

We can only surmise that this event presented an emotional challenge for both Sophie and Hans Christian. It may, however, have made an important positive contribution to science. The expenses for Ørsted’s 2½-year journey were significant. Fortunately, support from the Cappel Fund had been arranged by Manthey, who was a member of the board of the Fund. The stated purpose was for Ørsted to learn more about technical chemistry, especially porcelain manufacture and the brewing of beer. He soon realized that fundamental science was of far greater interest for him. Regarding the prospect of a career in technical chemistry he wrote “… I confess to you that this would not please me, for I have now begun the study of theoretical physics and chemistry, and the more I study, the more I see the necessity of continuing and the more I enjoy it, and I would be most reluctant to abandon the investigations which I have now decided to undertake” . Marriage to Sophie and the related expenses of “establishing a home” could have forced a career choice that would have precluded his discovery of electromagnetism in 1820.

It may come as a surprise that so little is known about Sophie Probsthayn and her connection to Hans Christian Ørsted. This is due in large part to the two-volume edition of his letters (Breve til og fra Hans Christian Ørsted) that was published by his daughter, Mathilde Elisabeth Ørsted (1824-1906), in 1870. All references to Sophie Probsthayn have been removed in this edition and crossed out, written over, clipped or torn from the original letters in Mathilde’s apparent attempt to protect her father’s reputation. As noted above, all of Ørsted’s private letters to Sophie have been destroyed. The quotation above from Ørsted’s letter of October 6, 1803 is not included in Mathilde’s edition and crossed out on the original. Mathilde was also prepared to make significant changes in the text. In a letter of May 28, 1802 Ørsted wrote “Here I thought of you, my Sophie, and wished that I could at least show you the lovely group, Cupid and Psyche”. Mathilde changes the original document to read “Here I thought of you, my brother, and wished that I could at least show you the lovely group, Cupid and Psyche”. (The words “my brother” are not included in the printed version.)

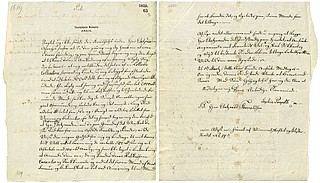

The next glimpse we have of the Probsthayns is from 1818. On May 16 Sophie’s brother Carl died in Copenhagen and was buried in the St Petri cemetery. At the time, it was reported that “he died in a state of mental confusion because he had become lost in his drawing”. Sophie was his sole heir, but there was nothing to inherit except for the expenses of his burial. Some two years later — between August 11, 1820 and March 1, 1821 — she sent an undated letter to Thorvaldsen in Rome. Reminding him of his long-standing friendship with her parents and her brother, she requested that Thorvaldsen lend her the sum of 500 rix-dollars. Although somewhat rambling, the letter is written in a beautiful hand. An excerpt containing its essential content is given below .

“I have been offered half of a lottery collection whereby I could see myself secure in the future by paying 500 rix-dollars, but I cannot pay this for the following reasons; I have, by thrift, accumulated 2000 rix-dollars, but I entrusted that money to an honourable and apparently wealthy man, who, however, has been made destitute by the recent upheavals, and therefore I shall have nothing in return at least for a long time. As I am completely without friends and acquaintances, I hereby take the liberty to ask your Excellency if, because of your former friendship for my late parents and my brother, you would show me the kindness to contribute to my future well-being by lending me the above-mentioned 500 rix-dollars, which I will repay in annual instalments of 100 rix-dollars. I have not hesitated to ask this of you as I know your honourable character and way of thinking, and because it is easy for a man of your wealth and connections to instruct someone here to arrange it and similarly retrieve it in the same way.

Your obedient servant, Sophie Propsthayn

My address is the corner of Vimmelskaftet and Klosterstræde No 14.”

Letter from Sophie Probsthayn to Thorvaldsen, dated between 11.th of August 1820 and first of March 1821.

We see from her address at the corner of Vimmelskaftet and Klosterstræde that she was living only 100 meters from the Lion Pharmacy, but we have no idea what she was thinking. Neither do we know what Thorvaldsen was thinking. There is no answer to her request and no indication that she managed to solve her economic problems.

Census data and the St Petri parish register provide the remaining available information about Sophie Probsthayn. In the census of 1834, she is listed as living at Lille Strandstræde 69 with the decorative painter Jean-Mathieu Baruël, his wife Dorothea Kirstine, and their son Jean Guillaume Euchaire Baruël, who was a student at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. Sophie’s occupation was given as needlewoman. According to the 1840 census, Sophie was still living with Jean-Mathieu and Dorothea Kirstine Baruël on Store Kongensgade. According to the records of the French Reformed Church, Jean-Mathieu died later that year. At the time of the census of 1845, his widow was living with her son Jean Guillaume, who was now a successful portrait painter. At some point, Sophie moved to the St Petri Nursing Home. Located on Larslejstræde, this institution was only a few steps away from St Petri Church. Its mission was to provide care and shelter for aged and poor members of the congregation provided that they were also Christian and sober.

Margaretha Sophia Probsthahn never married. According to the parish register, she died on March 23, 1843 and was buried on March 28, 1843 in the cemetery of St Petri Church. Unfortunately, Thorvaldsen’s wish that hers might be a life of “joy complete” was only briefly realized.

One question remains. Her various addresses – Vestervold, Amager Torv, Vimmelskaftet, Lille Strandstræde, Store Kongensgade, and Larlejstræde – were never more than a few minutes walk from St Petri Church. During much of this time, Hans Christian Ørsted’s life was centered even closer on Nørregade and Studiestræde. Did they ever meet? We will probably never know.

References

- Dan Ch. Christensen: Hans Christian Ørsted: Reading Nature’s Mind, Oxford, 2009.

- Karen Jelved and Andrew D. Jackson: “The Travel Letters of H. C. Ørsted”, in: Scientia Danica. Series H, Humanistica 8 vol. 3 (2011) I-XXXVII, 1-536. (This work is available for free here.

Last updated 25.10.2021