What Is Classical?

- Ernst Jonas Bencard, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 1994

- Translation by David Possen

This text was originally published in the journal Øjeblikket [The Moment], vol. 4, no. 19 (Winter 1994). It reviews the exhibition Fra Bartolommeo: A Master of the High Renaissance. Drawings from Museum Boymanns van Beuningen, Rotterdam, which was on display at the Royal Collection of Graphic Art, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, from 4.12.1993 to 6.3.1994.

Although Thorvaldsen’s name does not appear in this essay, it has been republished in the Thorvaldsens Museum Archives because its reflections on “the classical” also bear relevance for Thorvaldsen’s classicism. To see this, the reader is invited simply to replace all references to “Fra Bartolommeo” with “Thorvaldsen.”

“Classical is timeless”

The Royal Collection of Graphic Art at the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, is currently exhibiting the drawings of the Florentine painter Fra Bartolommeo (1472-1517), drawings that for the most part are preliminary sketches for his paintings. Fra Bartolommeo’s artistic career coincides approximately with the period called the High Renaissance, which stretches for about two decades starting around the year 1500. As is well known, the High Renaissance is regarded as the hotbed of classicism—or, rather, the site of its rebirth—in Western visual art. In this exhibit, Fra Bartolommeo is marketed alongside Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael as one (albeit hardly as famous as the others) of “the four forefathers of the classical style.”

In the Western visual arts, “the classical” and “classicism” are regarded as concepts with clear denotations. A classical image is one that portrays a harmonious, eternally valid order, a kind of absolute being that transcends the immediacy of phenomena, the passage of history, the transience of all things, or—to put the matter in thermodynamic terms—the universe’s ever-increasing entropy. Classicism suffers from a terror of change, or at least a disinclination to it. In a classical image, the ephemerality of time simply does not exist. The image is timeless, or rather untimely: classical art depicts no-time.

Fra Bartolommeo: The Marriage of St. Catherine of Siena

1511, oil on wood, 257×228 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris

And so it is with the imagery of Fra Bartolommeo. At first glance, his art seems by no means intended to depict his own contemporary age. Indeed: there seems to be a polar opposition between the political and religious chaos of Fra Bartolommeo’s own day and the static, unchangeable order portrayed in his art. Time and again, Fra Bartolommeo attempted to depict an untimely metaphysical order by returning to the same visual genre in his paintings: the so-called Sacra Conversazione, with God the Father, Christ, or the Virgin Mary placed along the central axis of the image, surrounded by saints, angels, and donors distributed in equal proportions on both sides. However, the conversation of the Sacra Conversazione is hardly an impressive one: each figure simply takes up its classical contrapposto, and then next to nothing happens. With such a compositional template, time almost seems to stand still. The figures have entered eternity; they have ossified as statues. (This classical visual formula, by the way, is the same one we imitate today when we attempt to preserve for eternity images of family gatherings, weddings, soccer teams, or school classes).

The impression of a sacred, statuelike, deathly immobility is only confirmed when we examine the genre’s modular unit, namely, the drapery-clad figure depicted in over half of the drawings presented in this exhibit: the drapery falls around such figures heavily, like a tent. Fra Bartolommeo availed himself of the practice, common in the Renaissance, of dipping the model’s robes in plaster, so that they would share not only in the statue’s color and material, but also in its stiffness. “Sculptural” is a word often used of such drawn drapery studies. (In classical art history, statues are regarded as less vivid and more deathlike than painted or drawn figures.) For Fra Bartolommeo, such drapery could also have been a reference to the burial clothes then in use for men in Florence at around 1500. It is also conceivable that some reference to the prophet Elijah and his magical mantle played a role here.

In both the compositional template of the Sacra Conversazione images and the draped figures depicted in them, the timeless, classical element seems identical to the statuelike, to the holy, and to death. (Small wonder, then, that funerary sculptures are also regarded as an essentially classical form of expression.)

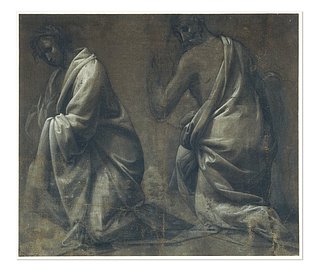

Fra Bartolommeo: Two Studies for the Kneeling St. Catherine of Siena, ca. 1508-1509, black chalk heightened with white, 264×291 mm

Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Anticlassical realism

Despite all his sacred paintings, Fra Bartolommeo does seem on two occasions to have regarded his own profession as too worldly: once when, under the influence of his spiritual mentor, the religious fanatic Savonarola, he burned his sketches of nude bodies during an auto-da-fé organized by Savonarola’s followers; and again when, after joining the Dominican Order as a monk, he ceased painting for four years. Such opposition to imagery, while paradoxical in a painter, has always lain latent in Christianity, and from time to time it has scurried out into the light. For Fra Bartolommeo, the worldliness he eschewed in painting was probably identical to the Renaissance’s enthusiasm for realism. The Renaissance, after all, is known for its development of the realistic image, which held sway over the visual arts during the four to five centuries to follow. At the time, realism was the avant-garde factor that gradually undercut the Middle Ages’ stiff iconic images. During the Renaissance, the cult of realism found expression first and foremost in the ever-increasingly correct reproduction of the anatomy and three-dimensionality of the the human body. By burning his own nude drawings, Fra Bartolommeo placed himself artistically as a conservative standing firm against the currents of his own age—and that, indeed, was an untimely and classic act. For the sacred classicist, all interest in the nude body had to be repressed, not only because the body is sensual and sinful, but also because any realistic reproduction of the body sets frail, perishable flesh—i.e., temporal matter—on display. The cult of the body, and realism generally, can thus be regarded as an attempt to introduce a temporal dimension into painting. The more an image avails itself of action, of movement, and of corporeal, realistic arbitrariness, the more it becomes the image of a moment, a picture in time.

Fra Bartolommeo, Study of the Drapery of a Kneeling Woman and Man, brown and white distemper on linen colored dark brown-grey, 273×316 mm

British Museum, London

In order to avoid such temporality and transience, the classicist Fra Bartolommeo cultivated a static order and wrapped the nude body in drapery. If, however, one examines his drapery studies more closely and thoroughly, one finds that they nonetheless reveal themselves to be the offspring of time. In fact, Fra Bartolommeo’s drapery studies are not nearly as stiff or dead as they are normally assumed to be. In one of his successive series of drawings of a single figure’s folds and armholes, we can detect an interest in bringing the drapery to life, in making them as three-dimensional and tangible as possible, in making them more subject to movement, in making the body behind them visible; and such tendencies are articulated more and more over the course of Fra Bartolommeo’s oeuvre. As a monk, indeed, Fra Bartolommeo cultivated such worldliness in silence, using drapery as a locus where realism, as the agent of worldliness in painting (at least during the Renaissance) could make its appearance without being hindered or excommunicated from on high. More generally, drapery seems to have contained a potential for liberation that would first fully unfurl itself in the Baroque, particularly in the art of Bernini.

For Fra Bartolommeo, then, drapery seems to have had two mutually conflicting functions. On the one hand, drapery classicizes and hides the body; it is statuelike, sacred, and timeless. On the other hand, drapery is also realistic, worldly, and in keeping with the times. Drapery can thus be regarded as the arena in which Fra Bartolommeo’s artistic conflict (and that of the Renaissance in general) between the sacred and the worldly came to the fore.

Even works by other artists of the High Renaissance—who, unlike Fra Bartolommeo, were unfazed by taboos against portrayals of the naked body—are governed by classicism’s impossible quest for timelessness. In the art of Dürer, for example, as well as in Leonardo’s famous Vitruvian Man (a.k.a. homo ad circulum, the man inscribed in a circle), the High Renaissance body was idealized in terms of geometric figures and doctrines of perfect proportions. What is more, art history continues to this day to use the designations figure studies, and figure groups characteristic of classicism, rather than referring to body studies and body groups, in a further instance of classicism’s attempt to spirit away the body’s temporality.

Fra Bartolommeo, The Crucified Christ, black chalk and red chalk, 278×205 mm, The Royal Collection of Graphic Art, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Classicism’s permanent crisis

We may conclude that, if one selects realistically represented bodies, nude bodies, or bodies covered in drapery as the basis for classicism—as did Fra Bartolommeo and the High Renaissance—then one will have set a ticking bomb into that same foundation. In the type of classicism constructed by Fra Bartolommeo and the High Renaissance, at least, a dialectic appears to be unavoidable; for this classicism seems to dissolve the very thing it constructs. Classicism, in short, seems to be in a state of permanent crisis.

For today’s zappers of images, who find euphoria in continuous change, classical drawings such as these have nothing to offer, since nothing takes place there. Classical art is often identified by this trait: it has the reputation of being academic, conservative, well-proportioned, ideal, exemplary, deadly boring … Yet if one bears in mind that classical art always—and Fra Bartolommeo’s case is no exception—will fail in this endeavor, then interesting cracks do open up within it. It is only when we regard the classical order together with its breakdown that it becomes possible, in that glimpse, to conceive fully of classical art’s impossible categories, such as the sacred, death, no-time, and je-ne-sais-quoi. Fra Bartolommeo’s classically draped figures thus demonstrate what the classical element in the visual arts truly is. It is the failed idealistic attempt to maintain an order that resists the wear and tear of time: a project that tries to withdraw itself from the rapid changes of everyday life, but which is nonetheless itself involuntarily whirled back into the flow of time. In sum, the Royal Collection of Graphic Art does indeed strive to make time stand still—alas, in vain.

Last updated 01.04.2020