Thorvaldsen’s Works at Hams Hall Rediscovered

- Kira Kofoed, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2016

This paper was delivered at the conference “Thorvaldsen & Great Britain”, Rome 19.-20.th of January 2016, Accademia di Danimarca & British School at Rome, by research fellow Kira Kofoed of Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen.

Old news, new discoveries

This paper is about a large, sculptural, interior decoration by Thorvaldsen that was situated at the now demolished manor house Hams Hall, at Warwickshire, Birmingham. It is an example—or case study, if you like, of how important and fruitful it can be to publish and study the original sources with new eyes as we intend to do in the ongoing project the Thorvaldsen Museums Archives published at the internet.

The complete large-scale commission has so far not been mentioned in the Thorvaldsen-research, and the few notes that are known on some of the artworks commissioned to Hams Hall have been intertwined with quite some errors—this despite the fact that a biography dating back to 1909, Life of Lord Norton, makes mention of a commissioned terracotta version of the Alexander Frieze, cf. A508, and that is very unique, as other contemporary accounts exclusively refer to commissions of the frieze in plaster and marble.

It is therefore the main purpose of this paper to re-insert the complete Hams Hall-commission into the Thorvaldsen-research.

An old letter

It was an undated letter from a not identified person to Thorvaldsen that started the whole investigation concerning Hams Hall. The letter is one of the letters from Thorvaldsen’s private papers that the sculptor’s first biographer, the Danish writer, Just Mathias Thiele, collected in Thorvaldsen’s home in Rome after his death in March 1844. Since then, the letter has made part of the physical Thorvaldsen’s Letter Archives at Thorvaldsens Museum that make the core of The Thorvaldsen Museum Archives on the internet.

The letter in mention is written in Italian, but clearly by a non Italian as both the sender’s name (F. Alleyne McGeachy) and the Italian language suggest. It is clear that the sender had become friends with Thorvaldsen during a former stay in Rome with his wife, as the tone of the letter is very warm and straightforward—for instance McGeachy starts the letter by writing:

Carissimo Amico [My dearest friend]

And, more humourously:

Ci è sempre gratissima la memoria della nostra amicizia con quel vecchio eccellente, che abita sul monte Pincio

[The memory of our friendship with that old excellent man, that lives at Monte Pincio is always very delightful to us.]

The most interesting sentence of the letter was the following one:

Tutte le sue opere sono arrivate benissimo è stanno adesso in campagna alla casa del mio fratello, dove tutti ammirono e domandono chi abbia fatto queste bellessime cose.

[All of your artworks have arrived in very good condition and are now installed at the countryside in the house of my brother, and everybody admires them and asks who has made these beautiful pieces of art.]

Identification of the sender

It was now of absolute importance to identify the sender in order to identify his brother and the mentioned manor house, and thereby the artworks. The evident match, the British politician Forster Alleyne McGeachy (1809-1887) had however no brother, so in the beginning I ruled him out. No other matches were found, but luckily it turned out, that McGeachy in 1834 had married Anna Maria Laetitia Adderley (1812-1841), sister to none other than Charles Bowyer Adderley, also known as the first Baron Norton, an extremely rich heir to the Adderley estates. Adderley became a politician and a philanthropist (with several streets and a park named after him). He was also McGeachy’s best friend. By marrying Adderley’s sister, McGeachy thereby became Adderley’s brother-in-law And given the many matching circumstantial details—as well as the linguistic quirks and errors in McGeachy’s Italian letter (for instance in the various ways in which he mentions his wife and her brothers)—it is therefore likely that, by the phrase “my brother’s house in the country,” McGeachy was in fact referring to his brother-in-laws’ house, which turned out to match Adderley’s manor house, Hams Hall.

The manor house Hams Hall, Warwickshire, England. Photograph from Lost Heritage / England’s lost country houses.

Hams Hall and Thorvaldsen’s artworks

Hams Hall was once found near the village of Lea Marston in North Warwickshire (close to Birmingham). From 1637 until its sale in 1920, the estate was in the possession of the Adderley family. In Charles Bowyer Adderley’s day, the appearance of the main building was marked by its restoration and expansion in 1764, a project that presumably was executed by the English architect Joseph Pickford (1734-1782). Adderley inherited the manor from his extremely wealthy great-uncle, who bore the same name: Charles Bowyer Adderley (1743-1826).

But now back to the investigation of the artworks by Thorvaldsen:

Presuming that Hams Hall was the place in mention, and Adderley the commissionaire, further investigation showed that Hams Hall was indeed described (although briefly) as having held artworks by Thorvaldsen. In most detail it was mentioned in the biography of Adderley published 1909 as Life of Lord Norton by William S. Childe-Pemberton, op. cit. The biography even held illustrations of the entrance hall and included a list of the six artworks purchased by Adderley:

The following is a list of Thorwaldsen’s works at Hams—the two first were gifts from the sculptor, the rest were done to order:

Singing Genii; (2) Playing Genii; (3) Cupid awaking the fainted Psyche; (4) Bacchus giving Cupid his first cup; (5) Cupid’s reception by Anacreon, wounded by dart of poetry in gratitude. These are all in marble. The terra-cotta frieze (6), round the cornice of the hall, represents the Triumphal Procession

of Alexander the Great into Babylon—the same as in marble at the Villa Sommariva Como and the Quirinal, Rome.

The last part about the terracotta version of the Alexander Frieze, cf. A508, was very surprising, as it was not stated elsewhere and a such replica at such an early time is very unique, as other contemporary accounts exclusively refer to commissions of the frieze in plaster and marble.

Most of the motives were easy to identify from the description, you can see them here—the numbers corresponds to the list just cited.

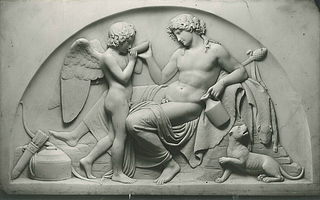

3. The relief Cupid Revives Psyche, A866.

4. The relief Cupid and Bacchus, cf. A407.

5. The relief Cupid by Anacreon, Winter, cf. A416.

6. Thorvaldsen’s frieze Alexander the Great’s Entry into Babylon, in a miniaturized and custom-fit terracotta version, cf. A508, in the entrance to Hams Hall. Photograph from Childe-Pemberton, op. cit., p. 22, undated; though according to Kingsley, op. cit., it dates from ca. 1909.

But as for the two first mentioned reliefs—the singing and playing genii, we had no direct matches at the museum. It was further complicated by the fact that an old correspondence was archived at the museum describing them as allegories of Music and Literature. This correspondence dates back to 1926 when the museum bought the relief deriving from Hams Hall, Cupid Revives Psyche, A866, from the London-based auction house Spink & Son. At that time all five marble reliefs from the then-recently demolished Hams Hall were offered the museum. The remaining four reliefs, however, were not acquired by the museum because the Museum’s director at the time declined to purchase them, reasoning that the other marble works were already well-represented in the Museum’s collections.

This correspondence from 1926 was the first clear traces of the Hams Hall commission to appear at Thorvaldsens Museum, and it stated, that photos of the Hams-Hall-reliefs had been sent to the museum. But due to a misplacement of these photos, the four other Hams Hall-reliefs were partly consigned to oblivion. The photos were never marked as related to Hams Hall, and at some unknown point they were even archived as illustrations of the museum’s own marble versions with the same motifs. Thus, after the 1926 correspondence was concluded, no one seemed to know what the Hams Hall reliefs looked like; even their motifs were partly forgotten, and other reliefs and other motives have later on wrongly been claimed or supposed to derive from Hams Hall.

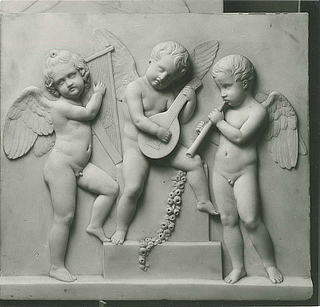

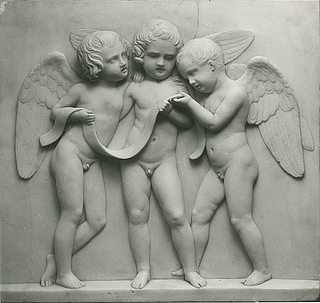

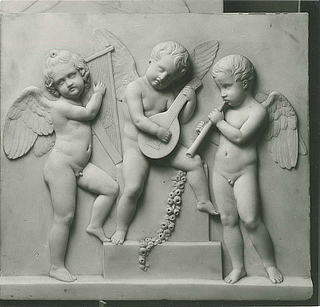

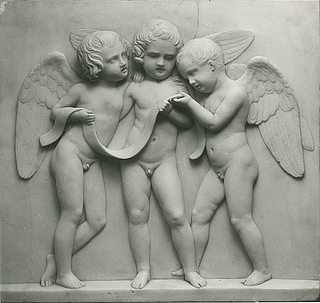

A lot of searching and comparisons of photos and artworks kept in the museum and elsewhere finally made it clear which photos had originally been sent to the museum. The last two marble reliefs were thus with certainty identified as replicas of the reliefs known as Singing Angels and _Playing Angels_—not genii. I will shortly get back to this confusion at the end of my paper.

|

|

| The Genii of Music Playing, jf. A588, Hams Hall-version. | The Genii of Music Singing, jf. A586, Hams Hall-version. |

As for the Alexander Frieze in terracotta, it appears that it was not included in the 1926 sale in London. Certainly it was not mentioned in the letter from Spink & Son nor anywhere else, but in the 1909 Adderley-biography.

From the same biography we know, that Adderley went on his grand tour in the early winter 1835. He reached Rome some time in December and stayed for three months. He then spent the spring and early summer in Sicily, Malta and Naples and stayed at Thorvaldsen’s place in Rome during his short stay in the city on his way back through Italy. He then travelled through southern France and Paris on his way back to England and reached home in September 1836.

While in Rome Adderley ordered the three large marble reliefs by Thorvaldsen and the Alexander-frieze in terracotta—at some still unknown point (during his stay in Rome or at the delivery of the commissioned art works) Thorvaldsen gave him the two minor marble reliefs as gifts—the ones with the singing and playing genii. We still do not know why Adderley ordered the frieze made in terracotta and not in marble or plaster as was usual.

When the younger Adderley purchased works by Thorvaldsen for Hams Hall in 1836, he did not yet reside at the estate, which was at that point rented out. But we do know that the artworks were installed during Adderley’s renovation of Hams Hall in the years to follow and finished 1841. Apparently they were all installed in the entrance hall. From the remaining photo we can only see the frieze and one of the marble reliefs. It is the relief Cupid and Bacchus, cf. A407, visible to the right of the door in the middle of the picture. The placement of the other four marble reliefs is not known with certainty at present, but it is most likely that Cupid by Anacreon, cf. A416, was set across from Cupid and Bacchus, i.e., on the other side of the fireplace visible in the picture’s lower right-hand corner.

6. Photo of Thorvaldsen’s frieze Alexander the Great’s Entry into Babylon, in a miniaturized and custom-fit terracotta version, cf. A508, in the entrance to Hams Hall. Photograph from Childe-Pemberton, op. cit., p. 22, undated; though according to Kingsley, op. cit., it dates from c. 1909.

The bust visible above the fireplace is difficult to identify because of the bad quality of the photograph, but we know that Adderley during his Roman sojourn commissioned a bust representing himself by the most popular Scottish, in Rome residing sculptor Lawrence MacDonald (1799-1878). Macdonald was in fact the sculptor who after Thorvaldsen’s death took over his studios at the Piazza Barberini, and he was one of the founders of the British Academy of Arts in Rome (closed 1936).

So just to sum up, what we know now about the art works by Thorvaldsen at Hams Hall today:

One relief is at Thorvaldsens Museum, one at the National Museum in Stockholm. The playing genii was probably bought by the same collector, that later donated the Singing genii to the Swedish museum, but it is still untraced.—The other two marble reliefs and the terracotta frieze have not been registered since the proposed sale in 1926.

| In marble | Location | |

| 1. The Genii of Music Singing, cf. A586 (gift of Thorvaldsen) |  |

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NMSk 1310 |

| 2. The Genii of Music Playing, cf. A588 (gift of Thorvaldsen) |  |

Location unknown |

| 3. Cupid Revives Psyche, A866 (commissioned work) |  |

Thorvaldsens Museum, A866 |

| 4. Cupid and Bacchus, cf. A408 (commissioned work) |  |

Location unknown |

| 5. Cupid by Anacreon, Winter, cf. A416 (commissioned work) |  |

Location unknown |

| In terracotta | ||

| 6. Alexander the Great’s Entry into Babylon, cf. A508 (commissioned work) |  |

Location unknown |

How did Adderley learn about Thorvaldsen?

What we do not know is how Adderley learned about Thorvaldsen? We know that he was interested in art and literature, and that the trip to Italy was his first tour abroad and that this grand tour of his must have made a perfect opportunity to start embellishing his future home Hams Hall. He could have heard of Thorvaldsen in many ways—from written sources or by being told by someone he knew. Apart from the enthusiastic and friendly McGeachy (which certainly knew Thorvaldsen well to judge by the letter cited) Adderley had at least one other family-connection that seems very likely to have influenced him on his choice of artist.

Adderley was a close friend of sir Thomas Dyke Acland (1809-1898), eldest son of Sir Thomas Dyke Acland (1787-1871) and Lydia Elizabeth, neé Hoare (1786-1856). Acland senior (id est the father) was a close friend of the Norwegian Knudtzon-brothers, who Stig Miss talked about earlier today, and as a young man Acland senior had traveled with Adderley’s father in Norway in 1802 during the interim Amiens-peace during the Napoleonic Wars. In fact they were shortly imprisoned in Christiania at peace end. It is reasonable to believe that they have visited the Knudtzon-family during this stay in Norway. We also know, that Knudtzon recommended Acland senior to Thorvaldsen, and being close friends—both fathers and sons in the Adderley and Acland families, they must have discussed Thorvaldsen at some point and thereby presumably contributed to the fact, that Adderley ordered the works of Thorvaldsen for Hams Hall—it is, at least, certainly reasonable to suggest.

Acland junior on the other hand and “our” Adderley went to Oxford together and afterwards they, like their fathers, traveled together. It was with Acland junior that Adderley went to Rome in 1835. Acland’s parents had already arrived in their yacht, Lady of St. Kilda, and the Acland-family lodged in the Villa Aldobrandini. Adderley, though, stayed at his sisters and brother in law’s place (the before mentioned Anna Maria Laetitia Adderley and Alleyne McGeachy that is). The McGeachy-couple lodged in Via Felice, Monte Mario. Hence we are back to the letter from the now identified McGeachy indicating a former stay in Rome and the starting point for the reinvestigation of the Hams Hall-commission.

The reliefs at Thorvaldsen Museum

And now—a final remark on the two reliefs with the singing and playing genii, because it is in fact the rediscovery of the full decoration at Hams Hall, which is the main reason why the reliefs now can be replaced in their original context.

Ludwig Müller, Thorvaldsen Museum’s first curator and author of the first museum catalogue, placed the two reliefs in the group of “Christian reliefs”—as Three worshiping angels and Three playing angels. He probably based his titles on the titles chosen by Just Mathias Thiele, who named the reliefs Three playing angels and Three singing angels, in his first biography on Thorvaldsen. The worshiping-part of the title was apparently Müller’s own invention and only makes the subject even more sacred.

|

|

| The Genii of Music Playing, jf. A588, Hams Hall-version. | The Genii of Music Singing, jf. A586, Hams Hall-version. |

The reliefs obviously form a pair and Thiele believed that they were related to a commission for a Communion table in the Cathedral of Novara, Italy (1833). However the reliefs’ almost square dimensions does not fit the rectangular measures of the Novara-commission, and the commissionaires asked specifically for a variant of another work by Thorvaldsen. And studying the contemporary written sources it turned out, that rather than angels they constitute genii (ie guardian spirits)—a motif that in general is much more widespread in Thorvaldsen’s art than angels.

Workshop accounts stated that the two reliefs were labelled as the “geni della musica” (the genii of music). By this the crucial contemporary sources were found. In other documents they were mentioned as “Singing Boys” and “Playing Boys” or as a pair as “little boys playing and singing”. Perhaps it is also the reliefs, entitled as just “Tré putti” (three putti). There was also a single early mentioning of a relief called “drei singend engeln”. Both the term “little boys” and “boys” corresponds to the collective term “putti”—a category that covers associations for both angels, pagan genii, cupids and the so called spiritelli, a kind of airborne spirits affecting the human body and emotions. And, as I mentioned, in the 1926-saleoffer of the Hams Hall-reliefs the two putti-reliefs were mentioned as allegories of Music and Literature.

All in all it seems reasonable to conclude that the two reliefs are to be included in the comprehensive range of motifs by Thorvaldsen, which illustrates the genii of various art forms and concepts, as the primary sources closest to Thorvaldsen’s workshop and to the first known owner of the reliefs agrees on this point. The reliefs are therefore today retitled The Genii of Music Singing and The Genii of Music Playing.

However, it is also conceivable that the later reading turning from the pagan to Christian iconography also was linked to the growing bigotry towards the middle of the last century or even that Thorvaldsen himself has blurred the picture so to speak by giving the genii more modern instruments like the mandolin and the harp instead of the double-flute, the lyre and the tambourine? By doing so the reliefs easily switch back and forth between a pagan and a Christian sphere—a kind of one size fits all-motive. This way of blurred perception is similar to the various ways of regarding for instance the statue called Dancing girl, A178, (1817) which some also assumed to be a “Bacchante”—a figure, that is, that on one hand can be seen as sweet and innocent and on the other as quite wild and licentious. These kinds of swifting meaning might be quite typical for Thorvaldsen—as also my collegues Ernst Jonas Bencard and Nanna Kronborg Frederiksen have touched upon. And with this, I will stop and thank you for listening.

The content of this paper is based primarily on my previous work published in the reference articles Thorvaldsens værker på Hams Hall and Fra genier til engle og tilbage igen. For further references, please consult these articles.

Referencer

- Michael Blain: The Canterbury Association (1848-1852): A Study of Its Members’ Connections, 2007, p. 9-10, 58.

- William S. Childe-Pemberton: Life of Lord Norton (Right Hon. Sir Charles Adderley, K.C.M.G., M.P.) 1814 – 1905: Statesman & Philanthropist, London 1909.

- Stefano Grandesso (and Laila Skjøthaug (catalogue)): Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), Milan and Copenhagen 2015.

- Nick Kingsley: “Adderley of Hams Hall and Fillongley Hall, Barons Norton,” in Landed families of Britain and Ireland.

- Kira Kofoed: Thorvaldsen’s Works at Hams Hall, The Thorvaldsens Museum Archives 2015.

- Kira Kofoed: From Genii to Angels and Back, The Thorvaldsens Museum Archives 2016.

- Julie Lejsgaard Christensen & Kristine Bøggild Johannsen: Thorvaldsen’s Ancient Terracottas, København 2015, p. 121-122, kat.nr. 68.

- Charles Dempsey: Inventing the Renaissance Putto, Chapel Hill & London 2001.

- James Hall: Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, London 1984.

- Jørgen Birkedal Hartmann & Klaus Parlasca: Antike Motive bei Thorvaldsen. Studien zur Antikenrezeption des Klassizismus, Tübingen 1979, p. 183-184.

- Ludvig Müller: Thorvaldens Museum. Tredie Afdeling. Oldsager. Første og andet Afsnit, København 1847, p. 112, kat.nr. 114.

- Ludvig Müller: Thorvaldens Museum. Første Afdeling. Thorvaldsens Værker., København 1848, p. 68, kat.nr. 585-588.

- Thiele 1848, p. 99-100.

- Thiele IV, p. 264 (1856).

Omtalte værker

Sidst opdateret 01.06.2017