Venus Priapus

- Nanna Kronberg Frederiksen, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2015

- Translation by David Possen

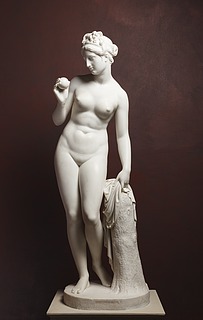

On this reinterpretation of Bertel Thorvaldsen’s sculpture Venus with the Apple, it is asserted that Venus, goddess of love, enters into a procreative relationship with the phallic god Priapus—and that Thorvaldsen thereby gives voice to a liberal philosophy of love based on freedom, equality, and desire.

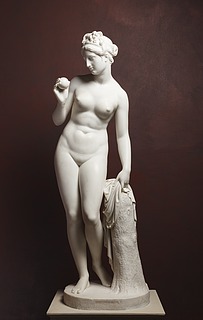

Fig. 1. Bertel Thorvaldsen, Venus with the Apple, marble, 1821-1828, A853.

Venus with the Apple (and with the Tree Stump)

In presenting the following reinterpretation of Bertel Thorvaldsen’s sculpture Venus with the Apple, my aim is to wrest the statue free of the puritanical gaze that has been fixed upon it for nearly two centuries. Innumerable interpreters have pronounced Thorvaldsen’s goddess-figure to be chaste and modest in expression, despite of the fact that, according to the myth, Venus had disrobed unblushingly only a moment previously, in order to have her naked body judged and evaluated by a lustful man.

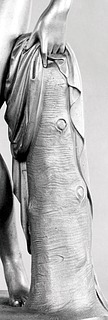

The basis of my reinterpretation, and its core, is a reevaluation of the tree stump that appears beside the goddess. Until now, this stump has been regarded as a decorative element, whose sole function is to serve as Venus’s clothes-horse. In my view, however, the stump is not that innocent: indeed, if one has eyes for the unexpected, one will discover that it resembles nothing less than a gigantic phallus, and an erect one to boot. I will argue that Thorvaldsen—consciously and clandestinely—furnished his statue with this special phallic, obscene element precisely in order to turn Venus with the Apple into an elegantly executed allegory of male and female love, sexuality, and creation—rather than a portrait of reserved chastity, as has otherwise been claimed.

Here I should note, both by way of introduction and for the record, that tree stumps are among the most common objects used to mask the supports that marble statues require to remain upright. Marble lacks the pressure strength that bronze (for example) has, and so marble sculptures require additional structural elements—so-called “supports”—to absorb or counterbalance stress or pressure within the stone. Through the ages, such supports have been camouflaged by a variety of means, such as crutches, columns, hanging drapery, or even a dolphin—to name a few. For his part, Thorvaldsen used tree stumps frequently as supports for his sculptures; but as far as I can tell, it is only in Venus with the Apple that the proportions and shape of the tree stump simultaneously prompt associations to a phallus.

Judgment of Paris

Venus with the Apple has its literary basis in the Greek mythological tale of the Judgment of Paris. This myth, which describes a beauty contest among three of Olympus’s strongest goddesses, was a cherished motif in the sculpture of Thorvaldsen’s day. Briefly, the plot is as follows:

All of the gods were invited to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis except for Eris (Lat.: Discordia), goddess of discord. Furious at her exclusion, Eris threw a golden apple, inscribed “For the most beautiful one,” in among the partygoers. The apple led to a quarrel among the goddesses Hera (Lat.: Juno), Athena (Lat.: Minerva), and Aphrodite (Lat.: Venus), each of whom claimed to be entitled to it. Zeus (Lat.: Jupiter) was asked to mediate the dispute, but because he was not a neutral party—he was married to Hera—he instead asked the gods’ messenger Hermes (Lat.: Mercury) to convey the three goddesses to the Trojan shepherd-prince Paris, who was to act as judge. Paris, who was ranging on Mount Ida with his sheep, took a glimpse at the three naked goddesses and chose Aphrodite, goddess of love, who promised in return that he would be granted Helen, the most beautiful woman on earth. Unfortunately, Helen was already married to the Spartan king Menelaus; and so Paris’s abduction of Helen to Troy led to a great battle, namely, the Trojan War.

Thorvaldsen’s Venus with the Apple is commonly described as a faithful reproduction of its literary source. Here is how a condensed compilation of previous interpreters’ descriptions of the statue might sound:

Thorvaldsen’s sculpture portrays a single, meaningful or so-called “pregnant moment” in the narrative, suggestive both of what has came before it and of what is yet to come. Still disrobed, Venus has just received her trophy, the Apple of Discord. She contemplates the apple while holding it up in her right hand; with her left hand, she reaches for her robe in order to put it on again. Her robe is hanging on a tree stump—an indication that these events are taking place in the countryside. The viewer, who is presumably familiar with Homer’s Iliad and the events of the Trojan War that it portrays, can readily imagine the subsequent events—the war and destruction—to which this scene will lead.

Beyond converging on this description, the majority of interpreters also agree that Venus with the Apple depicts a particularly chaste variant of the goddess of love. The following composite sketch includes the actual phrases used by a number of these interpreters:

Thorvaldsen’s Venus has “no doubt” disrobed “unwillingly,” and “longs” to “conceal her grace”; she “folds [her]self up again like a mimosa”; she “shut[s] out every intrusion from the surrounding world”; and her “virginal” appearance will “lead no young men to ruin on account of erotic love.”

This notion that the statue bears a chaste, virginal, and unattainable expression has dominated critical responses to it throughout the generations, from Just Mathias Thiele in 1831 to David Bindman in 2014. Generally speaking, what is lacking in such reactions is an explanation of why Thorvaldsen should have chosen to produce a Venus so remarkably demure as to clash directly with the myth’s maximally beautiful—indeed, sexy—Venus, who was able to garner Paris’s full attention by her mere presence.

It is my hypothesis that Thorvaldsen created his phallus-flanked Venus under the influence of enlightened and freethinking circles. These free relations, however, were soon replaced by a different and more prudish culture, which from Thiele and foreward more or less inadvertently came to conceal the more liberal aspects of Thorvaldsen’s work—including the master-stroke of setting his Venus beside an phallic tree stump.

Tracing the phallus

It was a chance event that opened my eyes to the phallus disguised as a tree stump. I was researching a bronze dinner set consisting of miniaturized copies of some of Thorvaldsen’s sculptures. This dinner set included a series of Thorvaldsen’s most potent divine and heroic masculine figures, together with an equivalent number of busty icons of femininity, including the wondrously beautiful Venus with the Apple. I was amused to discover that the bronze dinner set included appendable fig leaves in various sizes, for use in concealing the masculine figures’ penises. These leaf coverings were not originally included in the dinner set, but were produced by a prudish late nineteenth-century posterity, who felt the need to cover up Thorvaldsen’s naked human figures.

The fig leaves led me to think further about what one was not supposed to see. And they led me to see Venus with the Apple with new eyes: might it not be that by standing there and pulling her robe away, with her index finger resting nonchalantly on the “tree stump,” Venus was pointing the dinner guests to the very thing that they were not supposed to see—indeed, to an enormous such specimen, and an erect one to boot?

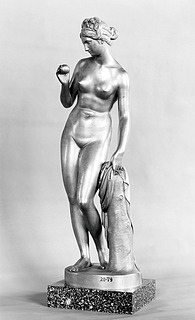

Fig. 2. Pietro Galli and Wilhelm Hopfgarten, modeled after Bertel Thorvaldsen, Venus with the Apple, gilt bronze, 1821-1824, The Royal Danish Collection, Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen, inv. nos. 20-79.

My discovery of the tree stump with the ambiguous appearance only piqued my curiosity further. It could hardly be, I thought, that the tree stump’s shape had been vulgarized during its conversion from marble sculpture to bronze statuette. Or could it? Or was it just that the gilt bronze gave the surface of the stump a more skin-like appearance, causing it to appear otherwise than intended? I took a look at both the original model in plaster, A12, and the completed sculpture in marble, A853. And even though first of these has an unembellished, flat surface, while the second has a raw, bark-like surface with knots and bumps, both versions give the same phallic impression. So I asked: what was afoot in Thorvaldsen’s sculpture?

Fig. 3, 4 and 5. Bertel Thorvaldsen, detail of Venus with the Apple, in bronze, plaster, and marble.

Aphrodite of Knidos

It was the Danish miniaturist Christian Horneman (1765-1844) who guided me along the first steps to a possible explanation. This is not because he makes specific mention of the tree stump—he does not—but because unlike the interpreters of later generations, Horneman decidedly did not regard Venus with the Apple as chaste. To Horneman’s eyes, on the contrary, Thorvaldsen’s Venus was so physically attractive that it awakened a kind of sexual euphoria in him, which he gave voice to unashamedly in a letter to Thorvaldsen dated 4.5.1829. Horneman wrote:

“Your great masterworks delight the souls of every connoisseur of nobility and deep feeling, but unfortunately there are so few of them here. Your Venus—the first time I saw it, I found myself in roughly the same mood as back in our days at the Academy, fortysomething years ago—I could hardly believe that Thorvaldsen’s art should call up feelings in me that not even a seventeen-year-old lass can rouse any longer.”

From Horneman’s point of view, then, Thorvaldsen’s Venus with the Apple was so physically appealing that she outshone even the young women of the real world, and indeed in a such a way as to rouse certain specific feelings in Horneman’s nether regions. If what is written between the lines is to be believed, Venus with the Apple made old Horneman into a “horny man” (so to speak) once more.

Certainly one may reject Horneman’s testimony as that of an old man with an overactive fantasy. But one can also regard his report as a sophisticated compliment, by which Horneman indirectly compared Thorvaldsen to Praxiteles, master sculptor of antiquity. Praxiteles, after all, went down in history as creator of the world-famous Aphrodite of Knidos, the first life-size female figure to be depicted naked in the history of classical art. And reportedly, this same Aphrodite of Knidos roused the same kind of desire in one man of Praxiteles’ generation as the feelings that Thorvaldsen’s Venus with the Apple reawakened in Horneman:

“There is a story that a man who had fallen in love with the statue hid in the temple at night and embraced it intimately; a stain bears witness to his lust.”

This anecdote, which derives from Pliny the Elder (ca. 23-79 AD), reveals in its totality that Praxiteles’ life-size, naked, and anatomically correct female figure was indeed regarded as something like a living woman, who was erotically stimulating to boot. This piece of marble, for which Praxiteles became so famous—at once beguiling and enticing the senses—became a paradigm for the classically-oriented artists of later ages. Innumerable Greek and Roman copies of Aphrodite of Knidos, as well as an unceasing series of paraphrases of the sculpture, attest to its special, archetypical status within European art history. Without a doubt, this is a statue that Thorvaldsen knew.

Fig. 6 and 7. Colonna Venus, Roman marble copy of Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos, Pius-Clementine Museum,

Vatican City, Rome, inv. no. 812. Front and back views.

When Horneman chose to “echo” Pliny the Elder with the story of how Thorvaldsen’s Venus sculpture had reawakened his youthful lust, his aim was not to expose himself to ridicule, any more than it was Pliny the Elder’s aim to titillate the reader with a perverse tale of sculpture-philia. The point was rather that the (re)awakened masculine lust vouched for the quality of the sculptures in question. The logic seems to have been that if Aphrodite of Knidos or Venus with the Apple, respectively, could succeed in seducing real men, this was because the sculptures incarnated or exuded the very power of the goddess of love. Put another way, a classically designed sculpture of Venus that lacked the power to seduce men would be less than a success. Precisely for this reason, Horneman’s unchaste remark about Venus with the Apple is in fact a compliment. And precisely for the same reason, “the stain” on the Aphrodite statue was a mark of its quality, which had moreover been permitted to remain—as an indexical proof of masculine desire—visible to all connoisseurs of art.

In this context, the question and challenge facing us are whether we can remove the veil of prudery that hangs before our eyes and instead behold Venus with the Apple with Horneman’s lusty gaze. Might it not be that Thorvaldsen’s Venus figure should be regarded not merely as an lofty goddess of love derived from a certain literary narrative, but also as a more realistic figure of desire—a sex object who turns men on? Is it plausible that Thorvaldsen consciously fashioned a tree-stump-phallus as a support for his Venus? And if this is indeed the case, how should we interpret the phallic stump? Is it a tangible reference to the masculine lust that the goddess awakens, according to the Knidos tradition? Is it an imagistic rendering of the desire by which Paris let himself be dominated when he chose Aphrodite (and so chose Helen)? Finally, how did Thorvaldsen’s contemporaries see the matter?

Priapus unsheathed

Among the Roman bronze figures in Thorvaldsen’s collection of classical art, I found a key that promised to open the door to a qualified hypothesis on the origins of the phallus disguised as a tree stump. These bronze figures include two in poses or situations that correspond to those I claim we see in Venus with the Apple, namely, that Venus 1) lifts up her robe and thereby 2) reveals an erect phallus.

- One such figure is a bronze statuette of the Greco-Roman fertility god Priapus (Gr.: Priapos) in his so-called anasyromenos-position. Lifting up his tunic in order to carry the garden’s fruit in his lap, Priapus manages to—almost by chance, it seems—reveal his most important attribute, namely, his gigantic phallus.

ILLUSTRATION COMING SOON

Fig. 8. Priapus, Roman bronze statuette, undated, H2049.

- The other such figure is a bronze statuette portraying a boy or young man in a walking position. He is clad in a so-called cucullus, a short cape with a pointy hood, covering the upper body and head so that only the face is free. He bears a secret, however, which is visible only to the initiated beholders, who know the trick: one can take the entire cucullus cape off, and so reveal an phallus, which now makes up the entire upper half of the figure.

Fig. 9 og 10. Walking boy wearing a cucullus, Roman bronze statuette in two parts, 0-200 AD, H2050. With and without top section.

These two Roman bronze figures can help us toward a fuller understanding of the matter. I will dare to posit that Thorvaldsen chose to integrate three of Priapus’s most important characteristics into his sculpture as distinct meaning-bearing elements: 1) Priapus’s giant phallus; 2) the robe that is lifted to reveal his phallus; and 3) the fruit that he carries. Why so? I believe that Thorvaldsen wished to offer a simultaneously classical-traditional and modern-sophisticated interpretation of Aphrodite of Knidos. In particular, I believe that Thorvaldsen labored to take account of the complexity of the goddess’s character in minute detail, by endowing his own Venus with two identities: an exoteric identity, open to all to see and read, and an esoteric identity, which could be unveiled by those who knew the trick of identifying the sculpture’s true priapic elements. Exoterically, Thorvaldsen’s Venus with the Apple is Venus Victrix, the beauty queen who has received her trophy in the form of a golden fruit; esoterically, she is Venus Priapus, the naked, nubile goddess who has roused the man’s spirit to activity with a single flick of her finger, which has now borne fruit: she is fertilized and fructified.

To further confirm this priapic interpretation of Venus with the Apple, it is fitting to take a closer look at the Priapus of antiquity—and specifically at the elements in that god’s cult with which Thorvaldsen may have been familiar, and which he may have further reinterpreted in his sculpture.

Cult of the god

Priapus was one of many phallic divinities to play a role in the creation mysteries of antiquity. According to certain myths, Priapus was born to Aphrodite by the ancient town of Lampsacus on the Hellespont near Phrygia, not far from Paris’ Troy. His father was either Dionysos (Lat.: Bacchus), Adonis, Hermes or Pan (Lat.: Faunus). Hera, too, played a role in Priapus’s DNA: she struck Aphrodite’s pregnant belly with evil intent, jealous that Paris hadn’t chosen her in the beauty contest. The result was that Priapus was born with an ugly, stunted appearance and unusually large genitals. In other words, the exaggeratedly large and continually erect phallus that was Priapus’s lot was in fact intended as a punishment, and indeed as a caricature of Paris’s masculine desire, which had directed itself exclusively at Aphrodite. Aphrodite rejected the ugly child, and Priapus instead grew up with shepherds, among goats and sheep.

Nevertheless, in the cult that grew up around Priapus in antiquity, the god’s phallus was regarded as neither obscene nor shameful. On the contrary, it was worshipped as a symbol of the masculine creative force. At root, the mysteries of creation concerned the capacities of plants, animals, and human beings to reproduce themselves and create new life by uniting the male and female principles. Here the male principle is understood as the active part that transmits and sows, while the female principle is understood as the passive part that receives and produces. In reproduction, both parts are necessary; hence the male and female can be said to occupy an equal but differentiated relation to one another. In polytheistic religions, such as Greek and Roman paganism, the various elements of this natural creation process are split up and assigned to numerous different gods, each of which is held responsible for its portion—though some could incorporate several aspects at once. Examples include:- Eros (Lat.: Amor, Cupid): sexual attraction, lust, erotic longing, the universal desire to beget or bear children.

- Dionysos: fertility, sexuality, ecstasy, wine, dance, masks, metamorphoses, wild nature.

- Chloris (Lat.: Flora): flowers, blooming, fruit.

- Genetyllis: childbirth.

- Hermaphroditos (Lat.: Hermaphroditus): sexual attraction between men and women.

- Aphrodite: sexuality, love, beauty, fertility.

Priapus was linked to sexual attraction, fertility, the cyclical turn and return of life and seasons, and not least with gardens. He made trees, bushes, and grapevines capable of bearing fruit, in part by serving as protector for beekeeping, and guarded the fertility of not only human beings, but also their domesticated animals, such as sheep and goats. Priapus served as guarantor for sexual desire on the part of both men and women; and he could, upon receipt of the proper votive gifts, heal impotence. As a god devoted to warding off evil, Priapus protected whatever he had set in motion—guarding the fruits and crops of the garden against theft, animal flocks against sickness, mothers and children against attack, and shepherds, hunters, and fishermen against bad weather, famine, and accidents.

The mystical union of Paris with Priapus, indicating that Priapus came into being as a kind of incarnation of Paris’s erotic longing for the goddess-woman, is confirmed by certain external facts: e.g., that they were both shepherds, both hailed from Phrygia, and both wore the Phrygian cap. For Thorvaldsen and his contemporaries, the Phrygian cap was not merely the symbol of a regional identity; it was also a symbol of freedom, marking a republican political affiliation. Both Paris and Priapus, therefore, could have been regarded by Thorvaldsen as masculine types who represented an unbounded and free masculinity—not only in a sexual sense, but also in a political context.

| Fig. 11. Unknown artist, Priapus, fresco from Casa dei Vettii, Pompeii, ca. 65-79 AD, Naples National Archaeological Museum [formerly the Real Museo Borbonico]. | Fig. 12. Unknown artist, Paris, marble, Roman, ca. 100-200 AD, restored in the 18th century, The J. Paul Getty Museum, inv. no. 87.SA.109. |

Figura veneris

It is my suggestion that Thorvaldsen read and understood the legend of the Judgment of Paris not merely literally, but also in an allegorical sense. For the Judgment of Paris is not merely a tale of a contest among three divinely beautiful competitors, and one young man’s difficult choice. It is also a foundational myth, a myth that treats the mystery of creation itself and the relation of fertility between man and woman.

Paris is an antihero. He rejects political power (Hera) and victorious prowess in battle (Minerva), i.e., gifts that otherwise would have made him into a traditional, masculine hero inhabiting prestigious social roles. Instead, Paris chooses Helen (Aphrodite), the most beautiful woman on Earth—and thereby a life of romantic and erotic love.

In traditional iconography, Venus is accompanied by Cupid, who shoots his arrow at Paris as a sign that the shepherd-prince will be (or will allow himself to be) governed by his erotic longing and procreative lust. Thorvaldsen, on the other hand, has his Venus flanked by a priapic tree stump-phallus. But the latter in fact has the same symbolic meaning: it too is a symbol of the masculine power of creation and fertilization. Paris is the active, male part who chooses freely, and delivers the fruit to his chosen one; Venus is the passive, female part, who arouses by virtue of her naked beauty, and who receives the fruit. The climax of the narrative occurs at the moment when the apple changes hands.

Christian Horneman helped us to see that Venus with the Apple is sexy, not chaste. And he opposed the tendency of his age toward prudery, which led, among other things, to Thorvaldsen’s Cupid Triumphant, cf. A22, having “a big devil of a fig leaf” mounted on his “sweet fructifying Priapus”. If we now dare to remove the mental fig leaf that until now has prevented us from seeing the Priapus, we can reconstitute a non-prudish interpretation of Venus with the Apple as follows:

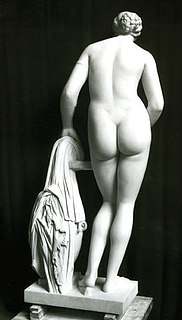

Thorvaldsen’s Venus with the Apple is an advanced artistic abstraction of the figura veneris, a sexual position that unites the female and the male in a single shape. Viewed from the front, Venus’s entire body is bent like a C or female “container,” bending around the masculine part, an I-shaped, priapic megaphallus, which for its part points diagonally upward. Venus’s marked posture and diagonal collarbone creates maximal distance between her hands. The drooping hand that lightly grazes the tree stump serves as the counterpart to the raised hand holding the apple; both hands attract attention. When viewing Venus from the right side, the onlooker—with a masculine-desiring gaze—can tenderly trace the contour line from the goddess’s Greek profile down over her shoulder, breast, abdomen and thigh.

Venus with the Apple is a worthy successor to Aphrodite of Knidos. Unlike the latter, however, the former is not of the Venus Pudica type. Thorvaldsen’s Venus is in no abashed hurry to cover herself again, but rather stands victorious and free in all her naked glory. The suspense provoked in the viewer by her bent body, which is surely poised to straighten at the very next moment, has hitherto called to mind a prim Venus, quick to clothe herself again. The secret truth, instead, is that Venus actually proceeds calmly here, letting her robe drag behind her. Taking a big bite of the apple, the goddess leaves the tree stump, uncovered, behind.

Fig. 13 and 14. Bertel Thorvaldsen, Venus with the Apple, marble, 1821-1828, A853. Frontal and side views.

The trend of the day

In 1804, the year he began work on Venus with the Apple, Thorvaldsen took a monthlong study trip to Naples and the ancient towns of Herculaneum, Pompeii, and Stabiae, which were destroyed by an eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. Both Venus and Priapus had been popular divinities in the region, which the Romans called Campania Felix [the Happy Plain] because of its unusually productive soil, fertilized by the many minerals spewed forth by Vesuvius’ eruptions. There has thus long existed a noteworthy parallel between the area’s mythological and geological characteristics: the fruitful joining of female and male was an analogue to the fertile union of soil and volcanic discharges.

At Pompeii, a town traditionally under Venus’s protection, Thorvaldsen observed an archaeological dig. Here Venus had had her own temple, and went by the name Venus Pompeiana Physica—an epithet that anchored her at once to the town, to generative nature, and to sensual erotic love. What is more, Thorvaldsen’s trip took place in the spring month of April, which had a special connection to Venus.

Thorvaldsen’s trip to Naples and the surrounding area was influenced not merely by the goddess of love, but also—and unavoidably—by Priapus. Numerous excavations of the three ancient towns had been underway since the mid-1700s, and these had uncovered a plethora of objects of art and daily use with phallic and erotic motifs. These objects stimulated onlookers’ fantasies widely, and Priapus became a common motif for numerous sculptures, authors, and scholars of the day. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s (1749-1832) collections of erotic poems from approximately 1789, Roman Elegies and Venetian Epigrams, offer apt examples of how Priapus was used to catalyze a free, gratified, and revolutionary male sexuality. Thorvaldsen too—at the time in the process of assembling a collection of models for use in his own artistic production—was similarly well-disposed toward this god with an unfettered creative desire, as the relatively large number of Priapus objects in his collection of classical artifacts attests.

At the archaeological museum in Naples, Thorvaldsen would have been able to see a Venus Priapus from Pompeii, namely, the famous statuette of Venus binding her sandal. Here a bikini-clad Venus stands and pulls herself upright by leaning partly on a tree stump, and partly on Priapus standing on a half-column, while binding—or loosening—her sandal with assistance from Cupid. This triad clearly served as a guarantor for sexual desire and sensual, erotic love. In his travels, Thorvaldsen had undoubtedly learned of the ancient custom of fashioning simple, phallic Priapus-poles out of available tree stumps and sticking them into the soil of kitchen gardens as fertility aids. He may also have known that Priapus was further identified with the Roman god Mutunus Tutunus, who was incarnated exclusively by a phallus.

| Fig. 15. Venus binding her sandal, also known as “Venus in a bikini,” first century BC - first century AD, statuette found at Pompeii, Naples National Archaeological Museum [formerly the Real Museo Borbonico], inv. no. 152798. | Fig. 16. Votive for Priapus, in the form of a colossal phallus with three smaller phalli, burnt clay with traces of red coloring, no earlier than 400 BC, H1268. Priapus’s epithet was Triphallus, a reference to his threefold degree of masculine power. |

I believe that Thorvaldsen felt great inspiration at the sight of the Pompeian interpretation of Venus and Priapus as two powerful, creative divinities of fertility. And I will dare to claim that Thorvaldsen used the “bikini Venus” with the priapic tree stump as the basis for his own work, transferring that sculptural pair to the shaping of his own goddess of love. To support this, I will—here, in closing—adduce another artist of Thorvaldsen’s day, namely, the English sculptor Joseph Nollekens (1737-1823). As far as I can see, Nollekens and Thorvaldsen make use of the same “tree stump trick”: both substitute an phallic tree stump for Cupid. Nollekens merely refers more explicitly to the Pompeian Venus Priapus in his 1773 Venus, inasmuch as that goddess-figure is also depicted in the process of removing her second sandal.

Nollekens’ Venus is part of a larger sculpture group that consists of Juno, Minerva, and Paris as well as Venus. This sculpture group was commissioned by the English politician and art collector Charles Watson-Wentworth (1730-1782). In 1768, Watson-Wentworth had acquired a classical Roman statue of Paris; he subsequently hired Nollekens to complement it with newly carved statues of the three goddesses, in order thereby to complete the tale of the Judgment of Paris.

Nollekens portrayed the three goddesses in various stages of disrobing. Minerva is still fully clothed, but is loosening her helmet somewhat; Juno has uncovered one of her breasts; but Venus—knowing what it takes to win—has only one sandal left to remove. To keep her balance while disrobing, Venus resolutely sets herself upon the tree stump. We now know that this posture is not merely a practical one, but is at the same time a simulation of the erotic love that Paris longed for, and which Venus fulfilled. Nollekens’ and Thorvaldsen’s Venus statues are thus quite closely related, indeed identical, in their allegorical message. Nollekens’ Venus is depicted just before the awarding of the apple, while Thorvalden’s is portrayed immediately afterwards. Both stimulate Paris’s priapic desire by virtue of their naked beauty.

Fig. 17, 18, 19 and 20. Joseph Nollekens, Paris’ dom, 1773-1776, The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Fig. 21 and 22. Joseph Nollekens, Venus, 1773, marble, The J. Paul Getty Museum,

inv. no. 87.SA.106. Front and back views.

Conclusion

Venus with the Apple offers a fine example of how complicated it can be to interpret Thorvaldsen’s sculptures on an iconographic and allegorical level. On an immediate viewing, the matter seems simple: Venus with the Apple represents a sequence within the Greco-Roman myth of the Judgment of Paris, in which Venus regards the trophy that she has received from Paris on account of her winning beauty. Looked at more closely, however, it seems there is nothing simple about this sculpture. Thorvaldsen has made use of an advanced visual language, in which the figure, its posture, style, attributes, and decorative elements form a unified system of meanings, fashioned in response to literary sources and sculptural prototypes of various kinds. Put another way, the sculpture is intertextual—to borrow a word from literary criticism.

The primary goal of this reinterpretation of Venus with the Apple has been to attempt to wrest the sculpture free of the interpretive tradition that has taken Thorvaldsen’s goddess to be a figure of chaste reserve. Our point of initiation into this reading was the tree stump on which Venus has laid her robe; this we analyzed as an phallic shape that refers allegorically to the Greco-Roman fertility god Priapus and his creative masculine power. A subtle but crucial element in this reading has been our interpretation of Venus’s discreet hand-gesture in lifting her robe as a variant of the so-called anasyromenos-posture—whose aim is to reveal or unveil the priapic giant phallus—rather than as an indication that the goddess wishes to cover herself up once again.

Closer scrutiny of Priapus’ genealogy has revealed that the garden- and shepherd-god’s particularly fertile phallus is an incarnation of the erotic lust to which the shepherd-prince Paris submitted when he chose Aphrodite/Venus. Put another way, Paris’s choice was so iconic and powerful that it gave rise to an entirely new divinity. It thus emerged that the myth of the Judgment of Paris does not merely concern a beauty contest among three of Olympus’s strongest female divinities, but also—more abstractly—the amorous, priapic lust that joins man and woman in a creative and fertile relation.

Thorvaldsen’s Venus with the Apple is here interpreted as a statue that relates to both of these semantic layers in the myth. The goddess figure is, at one and the same time, the victorious Venus Victrix in one layer, regarding her trophy with a winner’s satisfaction, and the creative Venus Priapus in another layer, entering into an erotic relation with the masculine element. By virtue of the Venus statue’s remarkably bent body and diagonally-placed hands, Thorvaldsen has succeeded in inscribing his goddess of love into a space of tension between apple and tree stump. And this makes possible a continuous alternation between Venus’s two identities: the exoteric and the esoteric.

An essential basis for this reinterpretation of Venus with the Apple has been the testimony to the statue’s sex appeal provided by Christian Horneman in his letter to Thorvaldsen. Horneman became the missing link, so to speak, who made it possible to penetrate behind the prudish, fig-leafed interpretive tradition, and lay eyes on a freer and more enlightened cultural environment. It emerged that Thorvaldsen was not the only one to be inspired by the classical world’s priapic-erotic cult objects and comparatively shame-free sexual culture. Indeed: such notable predecessors as Goethe and Joseph Nollekens had attempted to pave the way for such a pre-Christian, playful, free, and lusty erotics, with Priapus as their coachman. With Venus with the Apple, in short, Thorvaldsen articulated a liberal philosophy of love, entirely in keeping with the spirit of the age: one based on freedom, equality, and desire.

References

- Ernst Jonas Bencard: Shifting of Attributes – a Fundamental Feature in Thorvaldsen, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2013; “Attributrokering—et grundtræk hos Thorvaldsen,” in Passepartout – Skrifter for Kunsthistorie, vol. 15 (2009) no. 29, p. 136-148.

- David Bindman: Warm Flesh, Cold Marble, Canova, Thorvaldsen and their Critics, New Haven and London 2014, p. 96, 98.

- Mikkel Bogh: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Dansk Klassikerkunst, Copenhagen 1997, p. 35.

- Yves Bonnefoy (ed.): Roman and European Mythologies, Chicago 1991.

- DNP: Hubert von Cancik & Helmut Schneider (ed.): Der Neue Pauly, Enzyklopädie der Antike, Stuttgart & Weimar 2001.

- Anne-Lise Desmas: No Beauty Contest, The Getty Iris, The online magazine of the Getty, November 5, 2013.

- Stanislas Marie César Famin: Musée royal de Naples, peintures, bronzes et statues érotiques du cabinet secret, avec leur explication, Naples 1816, ed. and trans. “Colonel Fanin”: The Royal Museum at Naples, Being some Account of the Erotic Paintings, Bronzes, and Statues contained in that Famous Cabinet Secret, England 1871.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Romerske Elegier og Venetianske Epigrammer, Erotica Romana og Priapea, translated into Danish by Ole Meyer, 2015 [German 1790].

- Stefano Grandesso: Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), Milan 2015 [Italian 2010].

- Pierre d’Hancarville (1719-1805): Veneres et Priapi uti observantur in gemmis antiquis, 1771.

- Pierre d’Hancarville: Monuments du culte secret des dames romaines, 1787.

- Hargrave Jennings: Nature Worship, An Account of Phallic Faiths & Practices, Ancient and Modern, including the Adoration of the Male and Female Powers in Various Nations and the Sacti Puja of Indian Gnosticism, 1891.

- Jørgen Birkedal Hartmann: Antike Motive bei Thorvaldsen, Tübingen 1979, p. 63.

- Francis Haskell & Nicholas Penny: Taste and the Antique, The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500-1900, New Haven & London 1981.

- Christine Mitchell Havelock: The Aphrodite of Knidos and Her Successors, A Historical Review of the Female Nude in Greek Art, Michigan 1995.

- Homers Iliade, trans. Otto Sten Due, Copenhagen 1999.

- Richard Payne Knight: A Discourse on the Worship of Priapus, and its Connection with the Mystic Theology of the Ancients, 1786, to which is added Sir William Hamilton: An Account of the Remains of the Worship of Priapus lately existing at Isernia in the Kingdom of Naples, December 30, 1781, in: Ashley Montagu: Sexual symbolism, A History of Phallic Worship, New York 1957.

- Julius Lange: “Thorvaldsens Fremstilling af Mennesket,” Sergel og Thorvaldsen, Copenhagen 1886, p. 145-146.

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing: Laokoon, oder über die Grenzen der Mahlerey und Poesie, Berlin 1788 (1766); English edition here. Thorvaldsen’s book collection, M 30.

- LIMC: Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae, Zürich & Dusseldorf 1997, vol. VIII.

- Torben Melander: Antik erotisk kunst fra Thorvaldsens samlinger, Copenhagen 1983.

- Erik Moltesen: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Copenhagen 1929, p. 132-134.

- Ludvig Müller: Fortegnelse over Thorvaldsens værker, Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen 1848, A 11.

- Eugène Plon: Thorvaldsen, his Life and Works, Boston 1874, p. 202.

- Priapeia, sive diversorum poetarum in Priapum lusus, Sportive epigrams on Priapus by divers poets in English verse and prose, trans. Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890.

- Catherine Salles: L’Amour au temps des romains, Paris 2011.

- Pliny the Younger: Græsk-romersk kunsthistorie, Malerkunsten og terrakottakunsten, 35. bog af Naturalis Historia §§1-173, trans. Jacob Isager, Odense 1978.

- Pliny the Younger: Græsk-romersk kunsthistorie, Marmorskulptur og arkitektur, Stenarternes natur, 36. bog af Naturalis Historia, trans. Jacob Isager, Odense 1979.

- Laila Skjøthaug: “Catalogue of Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Work,” in: Stefano Grandesso: Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), Milan 2015 [Italian 2010].

- William Smith (ed.): Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 3 volumes, Boston 1867 (1844).

- William Smith (ed.): Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, Boston 1870 (1842).

- Harald Tesan: Thorvaldsen und seine Bildhauerschule in Rom, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna, Böhlau 1998, p. 26.

- Just Mathias Thiele: Den danske Billedhugger Bertel Thorvaldsen og hans Værker, Copenhagen 1831, p. 64.

- Johann Joachim Winckelmann: Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst, 1755.

- Johann Joachim Winckelmann: “Tanker om efterligning af de græske værker i maleri og billedhuggerkunst,” trans. Karsten Sand Iversen, in: Jørn Erslev Andersen (ed.): Sansning og erkendelse, Æstetikhistoriske grundtekster fra Baumgarten til Kant, Aarhus 2012.

Works referred to

Last updated 12.02.2021

![Unknown artist, Priapus, fresco from Casa dei Vettii, Pompeii, ca. 65-79 AD, Naples National Archaeological Museum [formerly the Real Museo Borbonico] Unknown artist, Priapus, fresco from Casa dei Vettii, Pompeii, ca. 65-79 AD, Naples National Archaeological Museum [formerly the Real Museo Borbonico]](https://fotoarkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/imgs/57/29/41342/collection/Priapus.jpg?Priapus)