Jean-Marie-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) and Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844)

Ingres’s attempt at “sculptural painting” hinges on the intense intellectual, aesthetic and technical inputs he received from actual sculptors but the relationships between Ingres and sculptors have drawn little attention so far. Only the tip of the iceberg, i.e. the contribution of antique sculpture to Ingres’s works has really been examined and publicized so far. For instance, the catalogue of the exhibition called ‘Ingres I Thorvaldsen’, that took place in Copenhagen in 1967 is almost systematically forgotten in subsequent reference bibliographies. As far as we know, not one researcher has ever written specifically on the very special bond formed, at the beginning of the XIXth century in Rome, by the young French painter and his main mentor outside academic training, the Danish statuary Bertel Thorvaldsen.

When the 1801 painting Prix de Rome laureate finally arrives in the “Urbs Aeterna” at the Villa Medici, the very place where French artists have been coming to study for centuries, the two most important living artists of the city are both sculptors: Antonio Canova (1757-1822) and Thorvaldsen, and their aesthetics could not be more different. Ingres should have logically gone to Canova, who is the friend of his own Parisian master, painter Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825). This painter was indeed accustomed to sending his sculptor pupils over to the Rome-based statuary, in order to further polish their art after their initial training in his studio. Thorvaldsen, on the other hand, was closer to German and Scandinavian artists. Ingres therefore made an interesting pivot by straying away from his former academic training and deliberately opting for the mentorship of the Danish sculptor. Despite their obvious differences of nationality, language, age, status, maturity and even artistic medium, the two men were drawn together by their shared love for art understood as gravitas and a demanding cult of form. As far as Ingres is concerned, this incongruous, and so far seemingly unnoticed, aesthetic brotherhood will be very fruitful thanks to a deep and generous sharing of artistic, archaeological but also technical knowledge.

Ingres might have met Thorvaldsen as early as 1807 through a Danish art amateur, Tønnes Christian Bruun de Neergaard (1776-1824), to whom he sold a drawing shortly after arriving in Rome. Or perhaps they connected through a fellow student of Ingres at Villa Medici, Charles-René Laitié (1782-1862), a sculptor who was engaged to Laure Zoëga, ward of the Danish statuary, from 1808 et 1810. Thorvaldsen’s relationship with the Danish archaeologist Jörgen Zoëga (1755-1809) was initially that of a mentee, however the relationship deepened over time and he was ultimately designated as Zoëga’s executor. The sculptor also took it upon himself to look after Zoëga’s children when he passed in 1809. In a letter dated in May 1809, the legal guardian of the Zoëga siblings, Danish diplomat Baron Hermann Schubart, writes to Thorvaldsen about the upcoming wedding between Laure Zoëga and Charles-René Laitié (se brev af 26.5.1809), probably because Thorvaldsen informally endorsed the role of a more hands-on father figure for the Zoëga children at the time. The sculptor’s efforts were in vain though because the engagement was called off in January 1810. Interestingly, 1810 turns out to be a very decisive year for the Ingres-Thorvaldsen relationship.

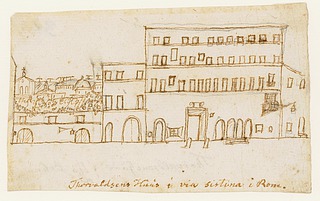

Ingres’s state-funded residency at the Villa Medici ended on the last day of 1810 but instead of going back to France, he decided to remain in Rome and to stay at 40 via Gregoriana, not far from the “Académie de France” but also in the same building where Thorvaldsen himself was living. The home of the Danish statuary in Rome was indeed at Casa Buti, a boarding house located in Palazzo Tomati. The front facade on Via Sistina spanned from n° 46 to n° 51 and that opened in the back on Via Gregoriana on n°40. For this reason, Dyveke Helsted reported that Ingres used to live “at Thorvaldsen’s” and had dinner with him every night for years, on the basis of German sculptor Christian Rauch’s telling. In the 1967 Copenhagen exhibition, the former head of the Thorvaldsens Museum notably put on display a drawing of Ingres picturing a living-room (fig. 1) that may have been his own there. More recently, Nanna Kronberg Frederiksen, a researcher and an archivist at the Thorvaldsens Museum, listed all the guests that she could trace back to Casa Buti (fig. 2) in the first half of the XIXth century.

Thanks to her work, we can establish that Thorvaldsen lived there from 1804 to 1842 while Ingres stayed from 1810 to 1813, until his first marriage. It is not difficult to imagine the two artists spending time together there, both sharing the same unconditional love for Raphaël and for a neoclassical aesthetic in sculpture. Furthermore, both would play music together: the whistle for the sculptor and the violin for Ingres (as in the French idiom “Violon d’Ingres”, that has made the mastering of that aforementioned music instrument by Ingres of widely public knowledge nowadays).

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 1: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Intérieur or A living-room decorated with paintings, 1806-1820 [1810-1813], lead pencil drawing and watercolour, 10.1×7.9 cm, Montauban, Ingres Bourdelle Museum (Inventory Number MI.867.4450). Joconde © Ingres Bourdelle Museum / G. Roumagnac.

Figure 2: Hans Christian Andersen, The House of Thorvaldsen via Sistina in Rome, 1833, ink on paper, unknown dimensions, Odense, Hans Christian Andersen Museum © Odense City Museums.

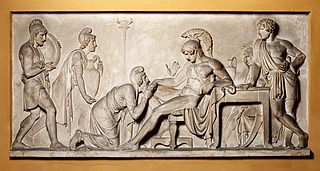

As of 1811, their friendship appears to strengthen their artistic proximity. For the last mandatory work that Ingres needs to send to Paris, he tellingly chooses the subject of Jupiter and Thetis (fig. 3). Although that topic can be traced back to sculptor John Flaxman (fig. 4) whose drawings they both loved and copied, we make the point that it can also be linked to the works executed by Thorvaldsen around 1808 and 1815. The pattern of a gracious youthful feminine figure attending to an imposing seated bearded man is indeed quite recurring in the sculptor’s inspiration, be it in his Hygieia and Aesculapius bas-relief (fig. 5), his Hercules and Hebe bas-relief (fig. 6) or the one of Jupiter and Nemesis (fig. 7). Coincidentally, we can wonder whether Thorvaldsen took a liking to the beseeching attitude of the ingresque Thetis as there is an echo of the pose in the kneeling salute and outstretched hand of Priam in his 1815 bas-relief (fig.8).

Figure 3: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Jupiter and Thetis, 1811, oil on canvas, 327×260 cm, Aix-en-Provence, Granet Museum (Wikipedia Commons).

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 4: William Blake (1757-1827), Thetis entreating Jupiter to honor Achilles, engraving made after a drawing by John Flaxman for the Iliad of Homer, 1805, engraving, 25.2×35.5 cm, London, British Museum (Inv. 1973,U.1189.9). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 5: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Hygieia and Aesculapius, 1808, plaster bas-relief, diameter 146.5 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A318).

Figure 6: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Hercules and Hebe, 1808, plaster bas-relief, diameter 147.5 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A317).

Figure 7: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Nemesis and Jupiter, 1810, plaster bas-relief, diameter 147.5 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A320).

Figure 8: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Priam Pleads with Achilles for Hector’s Body, 1815, plaster bas-relief, 93.5×193.5 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A492).

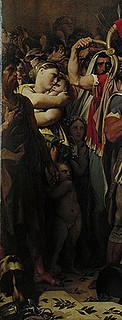

In February 1811, the Quirinal palace is restyled as “imperial palace of Monte Cavallo” and the Académie de France in Rome is charged with redecorating it, in order to make it a suitable place for the self-proclaimed “Emperor of the French” whose arrival is deemed imminent. On September 17th, Italian architect Raffaelle Stern (1774-1820) commissioned two big history paintings from Ingres for his decor program there: Romulus’ Victory over Acron (fig. 9), destined to the Empress’s private chambers, as well as The dream of Ossian (fig. 10), for the ceiling of the Emperor’s bedroom. Thorvaldsen was tasked with a frieze with a set theme for one of the largest halls in the same palace, Alexander the Great’s Entry into Babylon (fig. 11). Around that time, the young painter and the experienced sculptor therefore would work for the same sponsor on the same grounds during the day and would meet again in the evening at the same table. In that context, it is hard not to be reminded of the frieze of the elder when it comes to the 1812 painting of Ingres. For this work of art, which also celebrates military prowess, the painter in turn chose to narrate the victory of his Romulus in the form of a monumental painted bas-relief. Several other more precise details are also reminiscent of the concomitant draft of Thorvaldsen: the outstretched arm of the founder of Rome, parallel with a prancing horse; the shoulder pieces and the protective skirt of the breastplate raised by Romulus somehow hark back to the wings of the Victory angel that greets Alexander; the type of round shield used by soldiers in both works of art; the framing of the main scene by infantrymen, etc.

Figure 9: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Romulus’ Victory over Acron, 1812, tempera on canvas, 276×530 cm, Paris, E.N.S.B.A (Inv. DL 1969-2, lended to the Louvre Museum since 1969). (Wikipedia Commons).

Figure 10: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Alexander the Great’s Entry into Babylon, 1822, marble bas-relief, 55.5×2294.5 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A508).

Figure 11: J.-A.-D. Ingres, The dream of Ossian, 1813-1835, oil on canvas, 348×275 cm, Montauban, Ingres Museum (Inv. MI.867.70). (Wikipedia Commons).

Eventually Ingres established a workshop nearby La Trinité-des-Monts (fig. 12) while Thorvaldsen had set up his studio in the former stables of the Palazzo Barberini (fig. 13). The distance between the two was minimal as both artists were within a five-minute walking distance from each other and could therefore easily share opinions and advice on their respective works.

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 12: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Ingres in the process of painting Romulus’ Victory over Acron in his workshop of La Trinité-des-Monts, c. 1811, pen, brown ink and watercolour over lead pencil outline, unknown dimensions, Bayonne, Musée Bonnat-Helleu (musée des Beaux-arts de Bayonne) (Inv. 2224) © Bonnat-Helleu Museum

Figure 13: Hans Ditlev Christian Martens (1795-1864), Pope Leo 12. visits Thorvaldsen’s studio near the Piazza Barberini, Rome, on St. Luke’s Day October 18th 1826, 1830, oil on canvas, 100×138 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. Dep.18)

It is probably thanks to Thorvaldsen that Ingres was introduced to the greatest archaeology scholars of his time. The Danish sculptor was a close friend of the famous archaeologist Jörgen Zoëga (1755-1809). Further down the line in Rome he befriended the core group of Scandinavian, and German Antiquity specialists who had started the “Xeneion” in Athenes in 1810, such as Karl Haller von Hallerstein (1774-1817), Otto Magnus von Stackelberg (1786-1837), Peter Oluf Brøndsted (1780-1842), G. H. C. Koes (1-728-1811); they were eventually joined by Jacob Linckh (1787-1841) and Englishmen Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863) and John Foster (1787-1846). Ultimately Thorvaldsen went on to become a member of the Hyperboräïsche Römische Gesellschaft that was created in 1823 and assigned itself the mission of inventorying the archaeological and cultural patrimony found on Italian grounds.

Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863) (who later befriended Ingres, see fig. 14 and 15) started archaeological excavations on the Island of Aegina on April 1811. The architect uncovered the ruins of what was called at the time “the temple of Jupiter Panhellenius” as well as sixteen marble statues dating back from the transition era between Archaic Greek art and Classical Greek art. The sculpted figures were shipped to Rome and Thorvaldsen was commissioned to repair them by Ludwig I of Bavaria (fig. 16 and 17), which explains why he stayed in Aegina from the summer of 1816 until March 1817.

A well-known specialist of Ingres’ historiography, Henry Lapauze, started the idea that the Romulus painting (fig. 9) was indebted to the Aeginan statues for its figures. But the antique sculptures were actually conveyed to Rome after the completion of the painting. Ingres could have either seen sketches or engravings that were being quickly disseminated at the time or maybe through his archaeologist friends who were studying at the Villa Medici. To us, the most plausible explanation remains that the Frenchman got a peek at those archaeological breakthroughs thanks to Xeneion members, hence through Thorvaldsen’s friends.

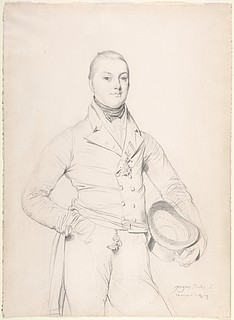

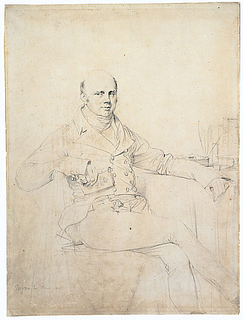

Figure 14: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Charles Robert Cockerell, 1817, graphite pencil on paper, unknown dimensions, Paris, private collection (Wikipedia Commons).

Figure 15: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Charles Robert Cockerell, 1817, graphite pencil on paper, 19.4×14.6 cm, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford (Inv. WA1998.179) (« Ingres a Messieurs / Lynk et Stackelberg / rome 1817 ») (Wikipedia Commons).

Figure 16: Ægineterne, vestgavlen, Afaia-templet, Ægina, omkring 500 f.v.t. med restaureringer – nu fjernede – af Bertel Thorvaldsen. Opstillet i Glyptothek München. © Thorvaldsens Museum

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 17: Recomposition of the pediment of the Aegina temple by Thorvaldsen, c. 1907. (Nordisk familjebok, 2nd edition, 1907, Vol. VI: “Egyptologi – Feinschmecker”, p. 1449-1450).

Thorvaldsen was very fond of antique artefacts and we make the hypothesis that he might have helped the young Ingres to acquire a taste in that field. In the collection of casts that were bequeathed to the museum of Montauban by Ingres, we do note two objects that belong to the Brøndsted collection and are identified as such by Meredith Shedd-Driskel, who also specified that the originals of the Hercules resting cast (fig. 18) as well as a Lapithe statuette can both be found in the National Museum of Copenhagen.

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 18: Hercules resting after an original bronze statuette from the Brønsted collection, undated, plaster casting, 9 cm-high, Montauban, Ingres-Bourdelle Museum (Inv. 173) (inventory by Meredith Shedd-Driskel kept at the Ingres-Bourdelle Museum in Montauban, a file named “Ingres Cast Collection 2”, p. 78).

On the other hand, a quick look at the 1787 ancient artefacts formerly owned by Thorvaldsen and still kept at his eponymous museum in Copenhagen allows us to draw a parallel with the cast collection of Ingres in terms of content. In both collections, we can find some objects from Ancient Egypt (adornments, funeral urns, amulets), a wealth of Greek vases (kraters, amphorae, alabastron, kylix, lekythos, skyphos, unguentarium) adorned with red of black paintings, some Greek and Roman busts and sculpted heads, fragments of antique statues, Etruscan objects such as vessels (like bowls with a foot, kantharos, kotyle, kyathos, loutrophoros, oinochoe, olla, olpe), jewels, mirrors or palmette antefixes also much appreciated by our painter, plenty of oil lamps and a bounty of pieces from architectural elements, of which a lot of snippets from Campana plates, and a glut of statuettes representing animals, children, athletes actors or small deities. Among those very rich collections, we highlight three examples of exact matches, two of them having already been pointed out by Meredith Shedd-Driskel.

The first one is a bas-relief called the Tabula Iliaca from the Capitoline Museums, found in the XVIIth-century near the Via Appia and that pictures the Trojan war. This particular panel became the subject of an article published in 1829 in the Annals of the Archaeological Correspondence Institute (now the German Archaeological Institute), of which Thorvaldsen was a member. Both artists bought a casting of this bas-relief and both of these cast plates are still stored respectively in France and in Denmark.

Meredith Shedd-Driskel also found similarities between multiple pieces pertaining in a series of Campana plates held in duplicate in Copenhagen and in Montauban, such as Three satyres and a silenus engaged in wine pressing (fig. 19 and 20). The Montauban-located Campana plate Satyres harvesting (fig. 21) also bears resemblance to the Campana relief with head of satyr and vines of Copenhagen (fig. 22).

Lastly, we suggest to consider together a fragment of a marble Serapis head (fig. 23) at the Copenhagen museum with a cast very similar in terms of traits and dimensions (fig. 24) in the Montauban compendium. In our view, the echoes between these collections tend to validate the idea of a rich intellectual dialogue between Thorvaldsen and Ingres.

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 19: Latium sculptor, Campana plate, Satyres engaged in wine pressing, 50 BC-50, fire clay, 33.7×42.3 cm, Montauban, Ingres Museum (Inv. MI.2006.0.2.2) © Ingres Museum

Figure 20: Latium sculptor, Campana plate, Satyres engaged in wine pressing, 50 BC-50, fire clay, 18×47.6 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. H1078) © Thorvaldsens Museum

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 21: Latium sculptor, Campana plate, Satyres harvesting, 50 BC-50, fire clay, 31.4×43.2 cm, Montauban, Ingres Museum (Inv. MI.2006.0.2.1) © Ingres Museum

Figure 22: Latium sculptor, Campana relief with head of satyr and vines, 50 BC-50, fire clay, 10.8×10.7 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. H1075) © Thorvaldsens Museum

Figure 23: Roman sculptor, Serapis head, probably reflecting a Greek Hellenistic work, IInd century, fragment of a marble head, 8.5 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. H1403) © Thorvaldsens Museum

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 24: Anonymous artist, Serapis head, undated, cast, 13.5×7 x 6.4 cm, Montauban, Ingres Museum (private collection of Ingres) (MONTAUBAN-ARLES 2006, p. 210 and notice n° 5, p. 385).

The friendship between the two artists was likely bolstered by the idyll started by Ingres and the eldest child of the late archaeologist Jörgen Zoëga, towards whom Thorvaldsen acted as an unofficial tutor. The romance bloomed after January 1810, when Laure Zoëga and Charles Laitié called off their engagement, and ended before December 1813, the date when Ingres finally married Madeleine Chapelle. A souvenir of this love story can still be found at the Louvre in the form of a portrait of a blonde and blue-eyed young woman by Ingres that seems to match the physical appearance of the Danish beauty (fig. 25).

Figure 25: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Blue-eyed young woman (Laura Zoëga?), 1807-1813, oil on paper, 27×20 cm, Paris, Louvre Museum (Inv. R.F. 1977-5) (WikiArt, public domain).

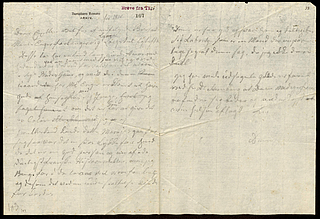

We counted five handwritten notes from Laure Zoëga in the archives of the Thorvaldsens Museum. Three of them are thought to date back to 1809 (“antagelig 1809”) and deal with lists of objects, furniture as well as financial statements. For example, one of those notes is titled “Expense account for my own use” (“conto di spese fatte per mio uso”) and lists small expenditures like the fixing of a sofa, travelling expenses or the sales receipts for the purchase of shoes destined to Laura and her sister. The fact that such trivial documents had remained in the possession of the sculptor makes us believe that he did engage in some kind of a hands-on tutorship over the children of his late friend. This claim of a trusting relationship between Bertel Thorvaldsen and Laure Zoëga can also be substantiated by two posterior warm letters from the young woman to the sculptor.

If he did not start it intentionally, Thorvaldsen has, for sure, been made aware of that love story in the making rather rapidly. This romantic relationship has been commented upon by several Danish art historians, notably Mathias Thiele in his book from 1852 and Haavard Rostrup in article from 1969; the latter writes that “Thiele writes that this liaison “sparked some discontentment in the peaceful house of the painter Labruzzi, where the signora Laura was a ” boarder.”

That statement is validated by the narrative brought up by a draft by Thorvaldsen that we found in the archives of his museum (fig. 26). To our knowledge, this letter has only been presented to the public in the Danish 1967 exhibition curated by Dyveke Helsted. In the letter, the sculptor says that a certain “Mr Enger” would like to marry Laura Zoëga, and, the right Danish pronunciation for “Ingres” is… “Enger”! Perhaps the legal guardian of the Zoëga siblings, i.e. the baron Schubart, doubted the intentions of the young Ingres with Laura. As an orphaned daughter to an egregious Danish scholar, Zoëga’s eldest child had received a small pension, courtesy of the royal Court of Danemark, as a dowry upon her first engagement. From that standpoint, she could therefore had been considered an “enviable match” for a self-serving struggling young artist. This could explain why Thorvaldsen took pains to shed a fairer light on Ingres, even concluding that Laura would be lucky to marry such a promising artist, whom he described as “a good guy” and “one of the best French history painters.”

Figure 26: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Letter to Baron Schubart, ca. 1812, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum Archive (m28-1812 nr. 107).

At the end of the year 1812, Ingres sent a formal request to his parents asking for their approval of his matrimonial prospect. Henry Lapauze is one of the first (and the few) French biographers who researched that French-Danish romance. He even devoted an entire section to it in his book about Ingres’s love life, including the unhappy final outcome.

We can therefore safely say that the wedding plans between Ingres and his Danish love were abandoned in 1813. According to Lapauze, Laura might have shown “an excessive love for dance. His comments echo the explanation given in the Copenhagen 1967 exhibition, that perpetuated a family account of those facts [by the Zoëgas?], in which Ingres became infuriated when he found his fiancée in the arms of a dashing cuirassier in a public dancing hall.

At the beginning of the XXth century, Danish art historian Carl V. Petersen went through the paperwork of Baron Schubart in the Royal archives of Denmark and discovered the “breakup letter” from Ingres. The text was in Italian but Petersen only published a Danish version, therefore limiting its audience and its overall impact on French and English-speaking researchers specialized in “ingresque” studies. In that letter, Ingres alleged that his parents had opposed their marriage project, which seems rather doubtful given the loosening of his family ties at the time. In any case, on December 4th 1813, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres married Madeleine Chapelle, a milliner freshly arrived from Creuse (a rather rural part of France), specifically summoned in Rome by her cousin for this arranged marriage that turned out to work perfectly well for both parties involved. The new household took up residence at n° 95 via Capo le Case, therefore Ingres moved out of Casa Buti and away from his friend Thorvaldsen.

However, a closer look at the works executed by the painter within the time frame of his departure from Casa Buti in 1813, to his departure for Florence in 1820, tends to refute the idea of a clean break between the two artists. During that period, in addition to Troubadour paintings commissioned by French clients, Ingres draws portraits of many tourists in Rome for their “Grand Tour”. Interestingly, many of those foreign visitors resemble Thorvaldsen’s models in the very same years. Is it possible that the sculptor, who was then a lot more famous that the young Ingres, sent his own clients to the novice portraitist who was struggling to sell any painting at the time? We can only speculate as to the connection, but the 1967 Copenhagen exhibition lists a first list of corresponding models between the two workshops:

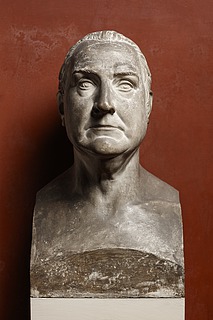

Henri-François Brandt (fig. 27 et 28), Alexander Baillie (fig. 28 et 29), Lady Pellew (fig. 30 et 31), Lord and Lady Bentinck (fig. 32, 33, 34 et 35), Pope Pius VII (fig. 36, 37, 38 et 39) and his cardinal Ercole Consalvi (fig. 40 et 41). The last two comparisons suggested by Dyveke Helsted are not as compelling to to us, as Ingres never had a private pose session with the Pope and had to go to the Holy week services in order to depict such a solemn moment in this mythical place. As for the Cardinal Consalvi, the time lag, between the portrait drawing in 1814 and the sculpted bust in 1824, is so great that it is highly doubtful that both artists had been able to recommend one another.

However, we add a few more names to the list of comparisons initiated by the Danish curator: the rest of the Pellew family, father and son (fig. 42 et 43), the Sandwich (Montagu) family (fig. 44, 45 et 46) as well as the portraits of John Russell (fig. 47), of his son Francis (fig. 48) and his daughter Georgiana (fig. 49, 50 et 51).

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 27: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Henri-François Brandt, [1814-1817], graphite pencil on paper, 19.2×14.7 cm, Berne, Kunstmuseum (Hans Naef, Die Bildniszeichnungen von J.-A.-D. Ingres, Berne, Benteli Verl., 1977 (Vol. I), chap. n° 75, p. 119).

Figure 28: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Henri-François Brandt, c.1817, plaster bust, 55.2 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A241)

Figure 29: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Alexander Baillie, 1816, plaster bust, 59 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A262)

Figure 30: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Alexander Baillie, 1816, graphite pencil on paper, 21.5×16.5 cm, private collection (WikiArt, public domain).

Figure 31: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Harriet Frances Pellew, 1817, plaster bust, 55 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A309)

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 32: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Portrait of the Honourable Mrs Fleetwood Broughton Reynolds Pellew, later Lady Pellew, born Harriet Webster, graphite pencil on paper, unknown date, dimensions and locations

Figure 33: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Lady Mary Cavendish-Bentinck, 1815, graphite pencil on paper, 40.8×28.7 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum (Pinterest).

Figure 34: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Lady Mary Cavendish-Bentinck, 1816, graphite pencil on paper, 21.9×17.1 cm, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Inv. 43.85.6).

Figure 35: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Lord et Lady William Cavendish-Bentinck, 1815, graphite pencil on paper, unknown dimensions, Bayonne, Bonnat-Helleu Museum (Wikimedia Commons).

Figure 36: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Lord William Bentinck, c. 1815, plaster bust, 49.9 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A261)

Figure 37: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Pope Pius VII, 1824-1825, plaster monument, 293.5 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A142)

Figure 38: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Pie VII, 1824, plaster bust, 67.3 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A270)

Figure 39: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Pope Pie VII at the Sistine Chapel, 1814, oil on canvas, 74.5×92.7 cm, Washington, National Gallery of Art (Inv. 1952.2.23, Samuel H. Kress collection) © National Gallery of Art, public domain.

Figure 40: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Pope Pie VII at the Sistine Chapel, 1819-1820, oil on canvas, 70×55 cm, Paris, Louvre Museum (Inv. R.F. 360) © Louvre Museum / Philippe Fuzeau).

Figure 41: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Cardinal Ercole Consalvi, 1814, lead pencil and white chalk, unknown dimensions, private collection (unknown location) © TOPofArt

Figure 42: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Ercole Consalvi, 1824, plaster bust, 73.9 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A271)

Figure 43: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Sir Fleetwood Edward Pellew, 1814, plaster bust, 51.3 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A260)

Figure 44: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Sir Fleetwood Broughton Reynolds Pellew, 1819, graphite pencil on wove paper, 30×22 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Figure 45: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Mary Ann Montagu, 1816, plaster bust, 69.9 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A267)

Figure 46: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Harriet Mary et Catherine Caroline Montagu, 1815, unknown technique and dimensions, London, Victor Montagu Collection (artchive.com).

Figure 47: J.-A.-D. Ingres, John William Montagu, 7th Earl of Sandwich, 1816, black and red chalk on paper, 33.5×21.9 cm, London, unlocated.

Figure 48: J.-A.-D. Ingres, John Russell, Sixième duc de Bedford, 1815, graphite pencil on paper, 38.9×29.1 cm, St. Louis, Saint Louis Art Museum © Saint Louis Art Museum

Figure 49: Bertel Thorvaldsen, [Francis] Wriothesley Russell, 7th Earl of Bedford, 1828, plaster bust, 50.9 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A285)

Figure 50: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Georgiana Russell, 1815, plaster bust, 42.2 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A315)

Figure 51: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Georgiana Elizabeth Russell, 1815, plaster sculpture, 100.3 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A173)

Figure 52: Georg Christian Freund, Georgiana Elizabeth Russell, 1866, marble sculpture, 101.2 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A773)

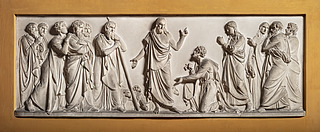

If Thorvaldsen and Ingres have stayed in touch even after the wedding of the latter with Madeleine Chapelle, then it could also be of significance that they worked on a similar topic between 1817 and 1820. The painting of Jesus Christ handing over the Keys of Heaven to Saint Peter (fig. 52) was ordered in 1817 but Ingres only delivered it to the Trinità dei Monti convent in 1820. Thorvaldsen also worked on the antependium of the Villa Poggio Imperiale chapel in Florence at the same time and he completed at least the plaster version of his bas-relief Christ Assigns the Leadership of the Church to Saint Peter in 1818 (fig. 53). Although the sculpted artwork comes in the form of a frieze, while the canvas presents a rather vertical plane, if we make the effort to visually isolate the central figures of the bas-relief, i.e. Christ and Saint Peter, then the similitude with the ingresque composition appears rather striking to us.

In both works of art, Jesus Christ is standing, clad in drapery, one hand raised to the sky while the other designates the earth, while Saint Peter, leading a small group of apostles (whose closest member keeps his hands clasped in prayer), kneels down in a respectfully beseeching attitude. And in both cases, the key of Paradise falls within the diagonal that goes through the arm of Jesus and points to his head in a much symbolic way.

Figure 53: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Jesus Christ gives the Keys of Heaven to Saint Peter, 1820, oil on canvas, 280×217 cm, Montauban, Ingres Bourdelle Museum (Inv. R.F. 97, deposit of the Louvre Museum) (signed: « J. Ingres Rom. 1820 ») (Wikiart)

Figure 54: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Christ Assigns the Leadership of the Church to Saint Peter, 1818, plaster bas-relief, 62.5×179.5 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A565)

In this light, we think that one may rightly wonder about “ingresque” or “thorvaldsian” lingering memories in the work of one another fellow artist, even after they stopped living under the same roof or even in the same city.

In order to substantiate that allegation, we first offer the comparison of the group of a mother with her children at the forefront of The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorien (fig. 55) with the Caritas plaster bas-relief by Thorvaldsen (fig. 56). That very detail in the painting from 1834 could well have been inspired by the plaster group that the sculptor was working on at the time that he met with Ingres around 1810. Although charity has been a recurring theme in Western Art, and all the more so in statuary, theological virtues have been handled in very different ways depending on epochs and geographies, as shown by the contrast between the Caritas by Jan van Delen (1610-1703) vs the Carità Educatrice by Lorenzo Bartolini (fig. 57). Our own comparison draws on several elements such as the very close embrace of the mothers who both cuddle their baby to their face, their standing attitude with a young boy touching them at knee-level, their draped costumes as well as their ribbon-clad buns that endow them with such distinctive yet similar profiles. If the raphaelesque reference is unmistakable in both cases (fig. 54), Thorvaldsen gave more scale and magnitude to that display of motherly love, therefore imagining a “ready-to-use” shape for Ingres to insert in his grand history painting.

Figure 55: Raffaello Sanzio (Raphael), The Mass at Bolsena (detail), c. 1511-1514, wall fresco, 660 cm-wide, Rome, Pontifical Palace (Room of Heliodor) (Wikipedia Commons)

Figure 56: J.-A.-D. Ingres, The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorien (detail), 1834, oil on canvas, 407×339 cm, Autun, Saint Lazare Cathedral (Centre National des Arts Plastiques)

Figure 57: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Caritas, 1810, plaster bas-relief, 67.5×48 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A598)

Figure 58: Lorenzo Bartolini, La Charité éducatrice, 1842-1845, marble sculpture, 192×80 x 47 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum (foto af Apollonia Stackler).

Secondly, we would like to reflect on the potential “kinship” between the grieving woman created by Thorvaldsen circa 1814 for the mausoleum of Johann Philipp Bethmann-Hollweg (fig. 59) and the attitude finally chosen by Ingres for his trademark Stratonice character (fig. 60) in the eponymous painting that he finished at long last back in Rome. As evidenced in preliminary drawings executed before he came to Rome for the first time (fig. 61 and 62), the first attitudes envisioned by Ingres for his Stratonice were rather different from the one he finally settled for, after meeting Thorvaldsen. The only common point being that the painter always intended to picture Stratonice with downcast eyes. The bas-relief of the Danish sculptor may have given Ingres the idea of a more tormented and huddled position. It could also be that his elder generously shared his archaeological knowledge with him and showed him some ancient objects that may have inspired him in the first place, such as the high relief on the attic funerary stele discovered by his friend Otto Magnus von Stackelberg (1787-1837). That antique artefact displayed a very moving young woman in an attitude typical of grief in antique Greece (fig. 63). In any case, the bas-relief by Thorvaldsen could be a key link between the ancient Greek symbols and the 1840 painting by Ingres.

Figure 59: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Woman Mourning, intended for the Monument to Johann Philipp Bethmann-Hollweg, 1814, plaster bas-relief, 88.5×33 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A734)

Figure 60: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Antiochus and Stratonice (detail), 1840, oil on canvas, 57×98 cm, Chantilly, Condé Museum (Inv. PE 432, Tribune room) (Wikipedia Commons)

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 61: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Stratonice or The illness of Antiochus (detail), [1806-1807], graphite, lavis gris et brun on paper beige, 25×40 cm, Paris, Louvre Museum (Inv. R.F. 1440) © Louvre Museum

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 62: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Stratonice or The illness of Antiochus (detail), unknown date, graphite pencil on tracing paper, 22.1×31.3 cm, Montauban, Ingres Bourdelle Museum (Inv. MI.867.2193) © Ingres Bourdelle Museum / G. Roumagnac

Figure 63: Attic sculptor, Funerary marble stele found in Acharnes (Menidi, Athens’ suburbs), mid-IVth-century before J.-C., marble high-relief, 122.2×73.7×39.4 cm, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art (Inv. 48.11.4, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1948)

To this day, the ingresque Stratonice had often been described by art historians and critics as an heiress to the aesthetic type of the “Pudicity”. But it is also quite obvious that the final attitude chosen for the Stratonice is still a bit different from the most famous statues of that minor deity (fig. 64 and 65), especially when compared with the above-described grieving attitude of the women of ancient Greece. In our view, the ingresque Stratonice has indeed more to do with the portrait of Maria Fjodorovna Barjatinskaja (fig. 66) created by Thorvaldsen as soon as 1819 than with the long-time gold standard of the Pudicity, namely the Benghazi statue (fig. 64). The sculptor uses that same mourning or pensive posture again in his Heavenly Wisdom (fig. 67) from 1825, long before Ingres finished his Antiochus and Stratonice painting in 1840.

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 64: Unknown sculptor, The Pudicity of Benghazi, unknown date (found in 1695), Paros marble sculpture, 198 cm-high, Paris, Louvre Museum (Inv. MR 245 / Ma 1130, deposited in the Galerie des Glaces of Versailles) © Réunion des Musées Nationaux de France / F. Larrieu

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 65: Charles Normand, The Pudicity, antique statue (board XVIII), 1835, engraving, unknown dimensions (Charles-Paul Landon, Annales du Musée et de l’École Moderne des Beaux-Arts, Second edition, Paris, Pilet aîné Imprimeur-Libraire, Vol. 3, 1835, p. 35-36 © Bibliothèque Nationale de France).

Figure 66: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Maria Fjodorovna Barjatinskaja (1793-1858), 1819-1825, marble sculpture, 181 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A171)

Figure 67 : Bertel Thorvaldsen, Heavenly Wisdom, 1825, plaster sculpture, 290.5 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A143)

Finally we compare two drawings from Ingres (fig. 68 and 69) with a bust of Napoléon Ist by Thorvaldsen (fig. 70). Admittedly, the zodiac arch as well as the cartouche are missing in the sculpted device but, as for the rest, both compositions offer strong analogies: they both show the bust a young emperor crowned with laurels resting on a pedestal adorned with an eagle whose wings are spread wide. Could the two men have walked together through a gallery of antiques? Or did the one lend his graphic notes to the other? According to a note written by Fernandes Rose in 2008 about a similar drawing on tracing paper referenced in Joconde, a national data base run by the French Ministry of Culture, those sketches would date back from 1864 and would be related to a painting project that never saw daylight. He goes on to say that a canvas on that very topic had indeed been found recently in a private collection based in Geneva and that an engraving by Louis-Adolphe Salmon (1804-1895) after this painting had been inserted by Napoleon IIIrd in the first volume of his History of Julius Caesar. According to Ettore Camesasca, Ingres actually did paint a “grisaille” titled Jules César in 1862, as a model for an engraving destined to illustrate the above-mentioned book. However that engraving (fig. 71) appears rather different from the undated Montauban drafts and makes the thorvaldsian trail looks all the more plausible.

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 68: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Ensemble de la composition (à mi-corps, debout, nu, et avec un aigle au-dessus d’un cartel), [1864], lead pencil on vegetable paper (un trait de carreau), 38,8×28,5 cm, Montauban, Musée Ingres (Inv.MI.867.2617) Joconde © photo Musée Ingres / Direction des musées de France 2008 / G. Roumagnac

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 69: J.-A.-D. Ingres, César en buste, entouré d’un zodiaque, derrière un aigle au-dessus d’un cartel, [1864], lead pencil on vegetable paper, 36,2×24,3 cm, Montauban, Musée Ingres (Inv. MI.867.2618) Joconde © photo Musée Ingres / Direction des musées de France 2008 / G. Roumagnac

Figure 70: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Napoleon Bonaparte, c. 1830, plaster bust, 99.9 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A909)

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 71: Louis-Adolphe Salmon, César d’après J.-A.-D. Ingres, 1865, engraving, unknown dimensions (Histoire de Jules César by Charles-Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, Vol. I, Paris, Imprimerie impériale, 1865, engraving inserted between p. 213 and p. 216).

The second Roman stint of Ingres as director of the “Académie de France” from 1835 to 1841 certainly provided him with some renewed opportunities to cross path with his old Danish friend. The rekindling of this old friendship might even have started earlier.

We note that a great friend of Ingres, the archaeologist Jacques-Ignace Hittorff (fig. 72), whose spouse (fig. 73) was also very close to Mrs Ingres, stayed for some time in Casa Buti in 1833. Did he go there on the advice of Ingres? We cannot know for sure but there is no doubt that he met Thorvaldsen there as the sculptor was at the height of his glory (he employed about fifty workers in his nearby workshop at the time) and they both shared the same fascination for ancient Greek temples and sculptures.

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 72: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Jacques-Ignace Hittorff (1792-1867), 1829, lead pencil on paper, 27×21.5 cm, Paris, Louvre Museum (Inv. R.F. 31425) (signed “Ingres a Madame Hittorf/1829”) © Réunion des Musées Nationaux de France

Photo missing due to copyright

Figure 73: J.-A.-D. Ingres, Madame Jaques-Ignace Hittorff née Élisabeth Lepère (1804-1870), 1829, lead pencil on paper, 27×15 cm, Paris, Louvre Museum (Inv. R.F. 31426) (signed “Ingres a son/ami hittorf/1829”) © Réunion des Musées Nationaux de France

From 1829 to 1835, Thorvaldsen was also very close to the predecessor of Ingres at the Villa Medici, French painter Horace Vernet (1789-1863), upon whom he bestowed the title of “best painter of the century” in a private letter (9.6.1838) and with whom he also exchanged portraits (fig. 74 and 75). When the latter departed from Rome in January 1835, he was among the Scandinavian and German artists who organized a banquet in his honor and maybe among those who extended the invitation to Ingres. The strong relationship between Thorvaldsen and Vernet proves that, to a certain extent, such prominent artists living in Rome were bound to interact with each other at some point at the very least.

Figure 74: Bertel Thorvaldsen, Horace Vernet, 1834-1856, marble bust, 110.5 cm-high, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. A253)

Figure 75: Horace Vernet, Portrait of Thorvaldsen Modelling the Bust of Vernet, c. 1833, oil on canvas, 93.5×74.9 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. B95) (Inscription: Horace Vernet à Son Illustre ami Torwaldsen Rome 1833)

Indeed, according to Daniel Ternois, under the «reign» of Ingres at the Villa Medici, the director would open the doors of the “Académie de France à Rome” to all the artists of the city at least once a week for a tea party on Thursdays. We know for sure that he welcomed the Swedish sculptor Bengt Erland Fogelberg (1786-1854) there several times. Fogelberg was the pupil of German sculptor Christian Rauch (1777-1857), a friend of Thorvaldsen who also lived at Casa Buti. Given the close bonds between the Swedish, German and Danish sculptors, we can easily imagine that they may have come together at times to visit their French counterparts. For example, French sculptor Jean-Marie Bonnassieux writes to his Parisian master Auguste Dumont (1801-1884), who recommended him to Fogelberg and Carlo Tenerani (1789-1869), that he sees those Rome-based sculptors often at Villa Medici, as they come by frequently to see his works and give him pieces of advice on them.

Besides, the informal existence of such an international body of Rome-based artists actively discussing their art together at the time has already been widely acknowledged by researchers. The “Académie de France à Rome” was no doubt part of it. In a letter to Paris from 1835, Ingres prides himself on the success of his students’ exhibition with the other artists of the city.

Both Thorvaldsen and Ingres were members of and even presided over the Accademia San Luca, an association of Roman-based artists founded in 1577 whose headquarters are just 600 meters away from the Villa Medici as the crow flies. In a letter from 1837, sculptor Jean Bonnassieux narrates how all the artists of the city came together under the banner of San Luca, regardless of their nationalities, for a religious parade in order to ask God to free Rome from cholera.

So if Thorvaldsen and Ingres were not as close as they used to be at that time, it seems pretty safe to assume that they stayed in touch throughout the rest of their careers. In 1837, Vernet, who had been back in Paris for a while and has just heard talks of cholera in Italy, writes to French sculptor Paul Lemoyne (1784-1873) whom he urges to warn his friends Thorvaldsen and Ingres in the same letter, which looks like another proof of their shared social connections.

In 1838, Ingres writes to Vernet about a case of unknown content involving his sculptor student Pierre-Charles Simart (1806-1857) as well as “Thorvaldsen and Reinart [sic]”. We have put that mention in relation to the archives of the Thorvaldsens Museum, where we also found the mention of “a big favour” benefiting a young artist that is asked by the Danish sculptor to Vernet (9.6.1838) and whose details are to be explained by their “friend Rienhart [sic] and by a post-scriptum from M. Ingres” . Although the letter penned by Thorvaldsen states that the name of the young artist is “Mr Sievert”, it could make sense that this would be a case of “bad-writing deciphering gone wrong” and that the letter would actually deal with the destiny of Pierre-Charles Simart, who went on to become one of the mentees best loved by Ingres. That very letter also tells us that Thorvaldsen took such a strong interest in the career of that “Sievert” that he tried to convince Vernet to write in turn to the family of the student so they would keep supporting him financially. As seen with the “Enger” pronunciation of “Ingres” by Thorvaldsen above, that kind of practical mismatch (Sievert / Simart) could have also impoverished our reading and interpreting of the relationship between the two artists so far. Indeed, if that new interpretation (Sievert = Simart) was to be proved correct, we could relate as many as four letters from the Thorvaldsen archives in relation with Simart and hence, maybe cast a new light on the artistic beginnings of this famous French sculptor who might actually have started his career under some favourable thorvaldsian auspices.

Finally, we note that in 1838, when some plaster castings ordered by Ingres in Rome were damaged during their shipment to Paris, he would blame it on the “moulder of Thorvaldsen.” That unexpected reference to the workshop of his Danish friend and its workers suggests that Thorvaldsen and Ingres may have enjoyed a closer artistic complicity than initially thought.

That accidental unveiling of the proximity of Ingres and Thorvaldsen actually echoes the potential meaning of the frequent mentions of Pietro Tenerani (1789-1869) by Ingres in his correspondence: this Italian sculptor was a pupil of Thorvaldsen and became a leading figure of Italian Purism (Purismo), whose artistic credo merges with the convictions of Ingres regarding the imitation of Nature and Italian Primitives. The Italian statuary would often come to the Villa, where he went to draw as a student himself, in order to visit the young Bonnassieux, as said above, but also to discuss the best techniques for moulding antique artefacts with Ingres, who was obsessed with his project to “repatriate” plaster castings of antique statues that had been handed back to Italians after their initial forfeiture by the troops of the first French Republic and then those of Napoléon Bonaparte. Reading between the lines, the fact that, after the departure of Thorvaldsen from Rome in 1838, Ingres would turn to his mentee Tenerani for advice on how to best handle statues and plaster casting can be construed as an acknowledgement of the authority of the art of Thorvaldsen in the domain of sculpture.

According to the catalogue of the 1967 exhibition, Thorvaldsen brought home to Copenhagen three paintings (fig. 77, 78 and 79) by French landscape painter Athanase Chauvin (1774-1832), a close friend of Ingres who was also served as a best man at his 1813 wedding.

Thorvaldsen also owned two copies of a very special work by Ingres: a rare attempt at metal engraving (fig. 76) that had been widely acclaimed at the time of its making and even compared to the works of Van Dyck by Lapauze for “its accuracy, its vigour and its sharpness.” It gives us an idea of what Ingres could have done, maybe, had he chosen the hammer and the chisel.

Lastly, we would like to mention a very interesting hypothesis that Florence Viguier-Dutheil, curator of the Ingres-Bourdelle Museum, mentioned to us, namely that Thorvalsen may have gifted Ingres with a very precious token of friendship, i.e. a relic from Raphaël as both artists were deeply enthralled by the Italian painter. This sounds very plausible to us as our research led us to confirm that in September 1833, the artists of the Accademia di San Luca gathered for the opening of Raphaël’s sepulchre in the Pantheon of Rome (Santa Maria Rotonda). They wanted to check the authenticity of a skull deemed to belong to him but they actually found a complete skeleton. Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875) has described the subsequent funeral wake several times in his correspondence and has identified Thorvaldsen among the attendees. Thorvaldsen was a keen Raphael collector and the Copenhagen museum nowadays conceals a bit of chalk from the tomb of Raphael in Pantheon. Ingres was in Paris in 1833 and only came back to Rome two years later. But his will from 1866 states that he also owns ashes belonging to Raphael. This unlikely sharing across arts, countries and lives epitomizes the long complicity that bound the duo and underlines the relevance of seeking correspondences between their artistic pursuits.

Figure 76 : J.-A.-D. Ingres, Gabriel Cortois de Pressigny (1749-1823), 1816, etching, 21.2×30.9 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. E635)

(inscription: “J. D. Ingres fecit. Romae. 1816” ; below the engraving “Exquise politesse, entretien noble affable / Dignité sûre, esprit, piété véritable / Style animé, par coeur, tendre amour pour le Roi / Dans ce portrait, Lecteur, j’ai dit ce que tu voi [sic]”)

Figure 77: Pierre-Athanase Chauvin (1774-1832), View of the gardens of the Villa Falconieri, Frascati, 1810, oil on canvas, 62.2×74.5 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. B87)

Figure 78: Pierre-Athanase Chauvin (1774-1832), View of the gardens of the Villa d’Este, Tivoli, 1811, oil on canvas, 62.8×73.8 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. B88)

Figure 79: Pierre-Athanase Chauvin (1774-1832), Grotta Ferrata in the Alban Hills, 1811, oil on canvas, 62.2×74.5 cm, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum (Inv. B89)

Sidst opdateret 27.02.2026