Echoes of Antiquity: Thorvaldsen’s Collections as a Reservoir of Motifs

Thorvaldsen’s Museum in Copenhagen, inaugurated in 1848 as the first museum in Denmark dedicated to a single artist, is an aesthetic universe in which not a single detail has been left to chance. Here, examples of almost all of the works created by the sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770–1844) during his lifetime, from reliefs to equestrian statues, are exhibited in the high-ceilinged galleries and corridors. The sculptures are accentuated by the colors of the walls, which range from ochre yellow to caput mortuum, as well as the rambling decorative frescoes on the ceilings, and the mosaic floors of fired tiles—mostly inspired by Pompeii and Herculaneum, as intended by the museum’s architect, Michael Gottlieb Bindesbøll (1800–1856). Thus, art and architecture synthesize, like a beautiful poem set to the right music, thereby creating what the contemporary German composer Richard Wagner (1813–1883) called a Gesamtkunstwerk. The colored Greek, Roman, and Egyptian-inspired architecture complements the white Neoclassical sculptures: when art forms and aesthetics interchange as elegantly as they do here, one can be led to believe that this is the only way Thorvaldsen’s art could be presented.

View through seven galleries of the north

wing of Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenha-

gen. Above the door is The Birth of Venus

(inv. no. A348); to the right of the door

Amor and Bacchus (inv. no. A797); and

above the door in the adjacent gallery is

Achilles and Penthesilea (inv. no. A495).

However, the presentation of Thorvaldsen’s art is, naturally, also the result of selections and rejections. Despite the fact that he was an impressive draftsman who produced over 1,400 sketches, surprisingly not one of these is included in the permanent exhibitions. Since sketches did not have the status of independent artworks, when the museum was built, they were not accommodated. The same is true of his bozzetti (small clay and plaster models). The presentation of Thorvaldsen’s oeuvre is thus the product of the period in which the museum was founded. His collections of antiquities and artworks present a similar case. Thorvaldsen was a passionate collector and his collections belong to the museum. However, my hypothesis is that the way in which they are exhibited also expresses choices and the contemporary desire to control Thorvaldsen’s public image. Also, the collections and Thorvaldsen’s artworks are exhibited in separate galleries, making it difficult to understand the relationship between the two. My focus here is on reestablishing the connection between Thorvaldsen the artist and Thorvaldsen the collector, as a way of debunking some of the myths that surround him.

This article is structured into four sections, beginning with a characterization of Thorvaldsen’s collections, examining what their complexity reveals regarding his ideas about collecting. This is followed by an analysis of their presentation at the museum, and the ways in which this has been influenced by the agendas of the mid-eighteen hundreds. In an attempt to approach what the collections meant to Thorvaldsen, the third section strives to visualize his time with the collections in Rome before they became museum objects. On the basis of two written sources it emerges that Thorvaldsen lived in the midst of his collections and made active use of them. The fourth section uses two reliefs by Thorvaldsen, Hylas and the Water Nymphs (1832 and 1833, respectively), as examples of how he was inspired by his collections, his recycling of motifs discussed with reference to the German art historian Aby Warburg (1866–1929). On this basis, the article challenges the widely-held view of Thorvaldsen as a chaste, patriotic, and entirely original artist.

A Stock of Erudition

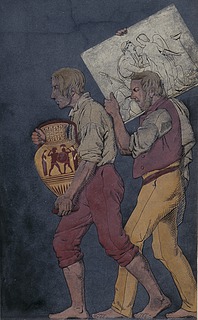

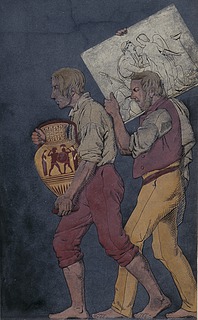

After approximately forty years in exile, on September 17, 1838 Thorvaldsen landed in Copenhagen on the frigate Rota and was met with a flurry of attention. He had brought a large consignment of his works with him as a gift to the city, donating his collections to the Danish capital on the same occasion. It would be easy to imagine that the collection of an avowed Neoclassicist, who was called ‘the Phidias of today’ after an outstanding Greek sculptor from Classical Antiquity, would consist exclusively of antique sculptures. [1]I However, as shown in the painter Jørgen Sonne’s (1801–1890) frieze on the façade of the museum (1846–50), which depicts Thorvaldsen being applauded at the customhouse while Rota’s cargo is carried ashore, he also brought items including Greek ceramics home with him. Thorvaldsen’s collections are, in fact, impressively comprehensive. Whilst the emphasis is on Classical Antiquity, they span from Egyptian amulets to Romantic paintings, covering almost five millennia, from the early-dynastic period in Egypt (circa 3000 BC) to the eighteen hundreds.

Jørgen Sonne. Two working men with

a Greek vase and Thorvaldsen’s reli-

ef Winter. Detail of the frieze on the

outer walls of Thorvaldsen’s Museum,

1846–50. Colored cement rendering.

Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen.

From the very beginning, several of the collections were incorporated into the design of the museum. As was the case when it first opened, the collections of antiquities and paintings are still prominently displayed in virtually the same way, installed along the length of the first-floor’s south and north wings, respectively. The collection of plaster casts was also represented on the first floor at the opening with nine replicas of famous sculptures, however this collection has since led a turbulent life. The current group of casts in the basement was selected in 2012. In addition to these three large collections, part of Thorvaldsen’s library is on display, as is a small medal collection from his own time. These collections can be seen as the bright side of the moon, so to speak, since others are not permanently represented in this way, and are therefore essentially invisible. Among these, Thorvaldsen’s extensive collection of works on paper – drawings and graphic works – and his collection of life and death masks, alongside a number of dactyliothecae (boxes containing casts of carved stones) are not part of any permanent exhibition. Similar instances can be found in many museums, the usual explanation being lack of space, concern about the condition of the works, or traditional categorizations of certain art forms as being more legitimate than others. However, this does not make the reduction of Thorvaldsen’s collections any less dramatic. A factor that also plays a role is the censorship or modification of the past, which to some extent has been handed down to the present. What follows gives an impression of the three large, visible collections: the antiquities, paintings, and plaster casts.

The first director of Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Ludvig Müller (1809–1891), was responsible for the meticulous and systematic display of the collection of antiquities in Bindesbøll’s tall glass cabinets and wide display cases, the insides of which are painted in luminous colors such as vermilion and light ochre. Here, a vast collection of antique signets and gemstones (engraved gems, glass pastes, and cameos) exhibited in a voluminous display case is pivotal (figure two). For decades Thorvaldsen was absorbed by the miniature world of these richlycolored stones. He became a self-taught expert and by the time he died had over 2,000, many of them from excavations in Etruria around 1830. [2]II

Greek and Roman gems. From upper left corner: Apollo

with lyre; erotic scene; sleeping Ariadne; Heracles and the

Nemean lion; erotic scene; foot of Hermes; Eros chasing a

butterfly; muse holding a scroll; scorpion; scorpion; Venus

Victrix, 100 BC–400 AD. Plasma, garnet, cornelian, obsidian,

amethyst, hyacinth, agate, nicolo onyx, and onyx, heights

vary from 0.8–2 cm. Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen.

The collection of Greek black- and red-figure ceramics is also largely from the contemporary excavations in Etruria, whereas parts of the diverse collection of metal artefacts, ranging from apotropaic household gods to bronze mirrors and gold jewelry, are primarily Etruscan and Roman. The supply of archaeological artefacts thus played a key role in what Thorvaldsen purchased. He allegedly found antique marble sculptures inordinately expensive: his relatively small collection (comprising primarily Roman copies of Greek works) includes many fragments, the rationale apparently being that a good fragment was preferable to a complete yet costly work. [3]III The marble works share a room with the terracotta collection, including the Roman oil lamps decorated with everyday motifs, of which Thorvaldsen was an enthusiastic collector. But several of his learned friends also had an influence on his collection of antiquities. His acquisition of the fine Egyptian collection, which includes amulets, statuettes of gods, and ushabti figurines was certainly inspired by Thorvaldsen’s mentor during his youth, the archaeologist Georg Zoëga (1755–1809). [4]IV The collection of antique coins was influenced, among others, by the archaeologist and philologist Peter Oluf Brøndsted (1780–1842), also because he borrowed money against his collection of coins and books that he never repaid, which is why they fell to Thorvaldsen.

Statuette of the dwarf god Bes. Egyptian,

late period or later, after 664 BC. Egyptian

faience, height of 8.9 cm. Inv. no. H71.

Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen.

Around four-fifths of Thorvaldsen’s painting collection consists of works from Thorvaldsen’s lifetime, and a selection of this contemporary art of the past fills nine galleries in the north wing. The remaining fifth, mainlyby Old Italian Masters, is represented by a few works hung in the collection of antiquities, such as the wing of an altarpiece of The Virgin and Child by Lorenzo Monaco (1370–1426). It was the theater painter Troels Lund (1802–1867) who selected the paintings in the run-up to the opening of the museum. In 1838, Thorvaldsen had brought over 260 paintings home, most of which he sourced among his social circle in Rome. Many of these he purchased to support younger, poorer colleagues, and there were also instances of a struggling colleague using a painting as collateral for a loan. [5]V During the years 1838–44 the collection expanded to 364 paintings, of which fifty-three were auctioned after Thorvaldsen’s death. [6]VI Only 143 are exhibited. Most of the contemporary paintings are either (primarily Italian) townscapes and landscapes, or genre scenes with subjects such as festivities on the streets of Rome or quiet scenes among Italian winegrowers and fishermen, including the German painter August Riedel’s (1799–1883) A Neapolitan Fisherman and His Family on the Beach (1833). However, Thorvaldsen’s memorial living room, which is installed in the first gallery, is dominated by portraits of his Danish inner circle and paintings of his haunts in Denmark, like Heinrich Buntzen’s (1803–1892) Nysø Manor (1843), something that I return to below.

Unlike the virtually intact antiquities and painting collections, the collection of plaster casts has had, as mentioned, a checkered past due to the varying attitudes of different eras. With the exception of fourteen works, the entire collection was put into museum storage in 1970. However, since 2012 a large selection of the collection, arranged like a packed study collection by archaeologist Jan Zahle, has been installed in a corridor in the basement. [7]VII The completeness of the collection is rare, consisting as it does of 640 of the original 652 works, comprising complete pieces and fragments from both Classical Antiquity and the Renaissance. The exhibition shows some of the most famous sculptures from Classical Antiquity, like Venus Medici (third–second century BC), as well as two heads from the Laocoön Group (first century BC). However, there are also lesser-known works, including the relief Satyr and Dancing Maenad from Villa Albani (second part of first century BC). Unlike the market for antiquities, which fluctuated according to contemporary excavations, the market for plaster casts was more stable, enabling Thorvaldsen to follow his own tastes and needs to a greater extent. [8]VIII There are numerous examples of him using the plaster casts as a reservoir of motifs, for example an unidentified eagle from the first–second century BC (the model for the eagle at the feet of John the Evangelist (1839) in Copenhagen Cathedral. [9]IX

Thorvaldsen did not collect specific objects for a single purpose, but rather a large range of objects for many different reasons, and from a certain juncture, he would have had the future museum in mind. [10]X However, at its core, his collecting reveals a vast curiosity about visual expression and design that traversed period and media, as well as the desire to possess works that could stimulate this curiosity. Here, the advice of the influential German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) to artists, as formulated in “Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and the Art of Sculpture” (1755), seems highly apposite. Winckelmann advocates acquiring “a stock of erudition.” The artist needs to take “from the whole of mythology, from the best poets of ancient and modern times, from the philosophy of many peoples, from memorials of classical antiquity on stones, coins and implements” in order to acquire an advanced conceptual and visual vocabulary. [11]XI To a large extent, Thorvaldsen’s inclusive method of collecting seems to have been driven by this interest in depth and breadth aimed at developing his imagery.

Censorship and Modifications of the Collections

As mentioned above, several of Thorvaldsen’s collections are essentially invisible. Parts of the permanently-exhibited collections were, however, also prone to invisibility from the opening of the museum in 1848, probably to protect Thorvaldsen’s image. In 1851 the Danish author Meïr Aron Goldschmidt (1819–1887) writes that Thorvaldsen’s fame did not dawn on people in Denmark until a late point in time:

The people of Denmark lost sight of him for a whole generation. Over such time much is forgotten, especially when it is filled with events like those of yonder years … the rise and fall of Napoleon, one half of Europe turned against the other. And as for here at home: the Battle of Copenhagen, the bombardment, and the long period of adversity that followed in its wake. In the meantime Thorvaldsen was like a forgotten fortune that had appreciated with interest, and interest on that interest. But what a strange fortune! This son of the people, an unknown child born into poverty, had become a towering figure of marble revered by the entire world. Marble! Marble! [12]XII

As the sharp-penned author implies, after years of oblivion the Danes became aware of Thorvaldsen’s stature abroad, and as he more than implies, this became a source of speculation. The finances and geographical extent of the Danish kingdom had been considerably reduced, the Crown was insecure, and a new bourgeoisie was waiting in the wings, ready to move center stage. In this context Thorvaldsen was a godsend: a man of the people and an international celebrity, he had all of the potential to become a national rallying point. But how was this “strange fortune” to be administered? While the sculptor returned unknown to most, he had not led the life of a typical Danish bourgeois during his forty years in exile, and this was apparently a cause for concern.

Lamp with an erotic scene, Roman, 0–100 AD.

Fired clay, height 12.7 cm. Inv. no. H1189.

Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen

It was presumably to secure support for Thorvaldsen that works with erotic themes were censored throughout the collections. Of Thorvaldsen’s Roman lamps, Torben Melander writes that there is an over-representation of lamps depicting coitus: “Was the motif a particular interest of Thorvaldsen’s? Presumably so.” [13]XIII However, at the opening of the museum in 1848 only one of the eleven was on display. “Not, incidentally, a fate restricted to the Roman lamps, but the fate of all antiquities with an ‘obscene’ motif.” [14]XIV The many phallus and manus ficus amulets, as well as figurines of couples making love, are to this very day not to be found among the other bronzes in the display cases. [15]XV Similarly, a number of paintings with erotic content have been in museum storage since 1848. The plaster cast Sleeping Hermaphrodite (150–100 BC) was also stowed away from the beginning, despite the fact that it was undamaged and that exhibiting intact works was a priority. [16]XVI

Phallus amulets, the lower specimen with phallus,

male genitals, and manus ficus, Roman. Bronze,

respective heights of 3.6 cm, 3.6 cm, and 7.5 cm.

Inv. nos. H2107, H2110 and H2117.

Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen.

Another concern seems to have been whether or not Thorvaldsen was sufficiently patriotic. He had celebrated March 8th as his Roman birthday since arriving in the city in 1797, had been a central figure in Rome’s cosmopolitan circle of artists for decades, and despite repeated requests, had refused to use motifs from Nordic mythology, sticking firmly to Classical Antiquity. [17]XVII From this perspective, it could be seen as a problem that a large part of the collection of paintings depict Italian motifs. The prominent art historian Niels Lauritz Høyen (1798–1870), who just a few years earlier had held the seminal lecture “On the Conditions for the Development of Scandinavian National Art” (1844), was commissioned to curate a selection from the collection. Not surprisingly, only eighty of more than 300 works were found to be suitable. However, this caused internal conflicts. Lund took over and was undeniably more liberal in his approach. Yet the works that have been selected and the way in which they are exhibited still seem to promote the idea of Thorvaldsen as a nationally-oriented figure. The structure is that of a literary home-abroad-home narrative, with the invented memorial living room in the first gallery of the collection of paintings surrounding the visitor with paintings of Danish friends and localities, and the last gallery also being dominated by Nordic landscapes, including An Ancient Burial Mound at Raklev on Refsnæs (1839) by Johan Thomas Lundbye (1818–1848). [18]XVIII Thus, the many works in-between with non-Danish subjects are held firmly in place.

Finally, there was perhaps some unease at the fact that not all of Thorvaldsen’s motifs were the result of divine inspiration from Classical Antiquity, but that at a very palpable level he also borrowed motifs and made them his own. People increasingly revered the idea of the artist as genius, perhaps one of the reasons Thorvaldsen’s art and his collections were exhibited separately without any links between the two. [19]XIX A similar fetishism for originality could also underpin the cast collection repeatedly falling in and out of favor, alongside a longheld decision to avoid showing the dactyliothecae, and to leave in their boxes the life and death masks that Thorvaldsen often used as a basis for his portraits (including those of Pope Pius VII and Napoleon).

The issue regarding the process of Thorvaldsen’s art and collections becoming national heritage is that the mission was as successful as it was. Since then, he has generally been regarded as a decidedly unsensual artist: “Thorvaldsenian coldness is almost proverbial,” the author Johannes Vilhelm Jensen (1873–1950) writes. [20]XX The art historian Julius Lange (1838–1896) had a similar view of Thorvaldsen as unsensual when writing of the sculptor’s “revival of the imagination of Antiquity,” where he found the “spirit of the satyr” in abeyance, the spirit that epitomizes “the naughty side of Antiquity.” [21]XXI Lange also appointed himself spokesman for the persistent view of Thorvaldsen’s art as an expression of a Danish and Nordic “mind and mood.” [22]XXII In addition to which Thorvaldsen’s recycling of motifs was long ignored. [23]XXIII The adaptation of the collections may well have influenced Thorvaldsen’s image as a collector and an artist who was entirely original and tended towards the unsensual and Danish-Nordic.

A Motley Mess: The Collections at Thorvaldsen’s Place

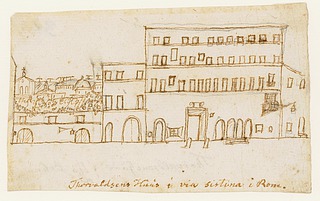

What was Thorvaldsen’s own relationship to his collections? From spring 1804 until his death in 1844 his Rome home was the boarding house Casa Buti at 46 Via Sistina, close to the Spanish Steps. Despite his success as an artist, he continued to live here in an apartment that surprised many of his guests with its modesty. The writer Frederik Christian Hillerup (1793–1861) reported that whilst “many other artists with a modicum of reputation in the world live like barons and earls, he who outshines them all through the immortal brilliance of his name lives in unassuming simplicity.” The only ornamentation in Thorvaldsen’s home were “[w]orks of art in such piles that the passage of the visitor is impeded.” [24]XXIV

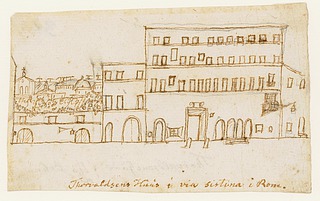

Hans Christian Andersen. Thorvaldsen’s house in via

Sistina in Rome, October 19, 1833. Ink and pencil on

paper, 74×13 cm. Inv. no. HCA/XXIII-A-1-0161. Hans

Christian Andersen Museum, Odense City Museums.

What follows is based on the memories of German painter Louise Seidler (1786–1866) and Danish author Just Mathias Thiele (1795–1874) of Thorvaldsen’s home. Seidler was a regular visitor at Casa Buti from late 1818 – mid-1819. Of the artists who lived there at the time, she writes that only Thorvaldsen had more than one room – three to be precise. [25]XXV The first was a small atelier filled with reliefs on easels and a profusion of “small figures” (bozzetti) on every available surface. As Seidler drily notes, “only with difficulty was a chair located to sit on, and nothing remotely akin to comfort.” [26]XXVI The bedroom was tiny, with a modeling stand jammed against the bed so that Thorvaldsen could get to work as soon as he awoke. A larger room was hung with paintings by impoverishe young artists and the tables were covered with a “motley mess” of all kinds of archaeological artefacts, vases, coins, and bronze figures.

Thiele’s memoirs five to seven years later (1823–25) reveal that, in the meantime, Thorvaldsen had established a more functionally appointed home with three additional rooms. The first room – the atelier- was now akin to a closely-packed museum’s gallery: “The walls are hidden,” Thiele writes, by paintings by “new masters and young artists who in Thorvaldsen had found an admirer of their art as happy as he was willing to offer support where he found talent gasping under the pressure of base conditions.” [27]XXVII There were also cabinets containing Greek vases, coins, gems, glass pastes, and books in the atelier, and on top of the cabinets, Egyptian and terracotta works. A table of marble fragments had drawers full of bronze figures, and there were engravings below a table in the middle of the room. The next room was a study in which Thorvaldsen modeled and sketched. Thiele describes a tub of wet clay in the corner, as well as a box containing his sketches on paper. The walls here were decorated with “sheets from the Boisserée collection that he alternated in frames.” [28]XXVIII Thus, what was in Thorvaldsen’s line of vision when he was creating sketches for his works – at least around 1823–25 – were lithographs based on Dutch masters including Rogier van der Weyden (1400–1474) and Hans Memling (1430–1494) from the major collection owned by the German collector Sulpiz Boisserée (1783–1854). These lithographs apparently succeeded each other in the same frames. [29]XXIX Thorvaldsen now stored his bozzetti in the room next door, and hung drawings of his own works by other artists on the walls.

Thorvaldsen’s humble abode had become slightly more hospitable since Seidler’s visit. In the next room people had the comfort of a sofa, and above the sofa was an 1821–22 portrait by the German painter Joseph Karl Stieler (1781–1858), “a gift from Thorvaldsen’s illustrious patron, His Majesty King Ludwig of Bavaria.” [30]XXX The bedroom was now a combined study-bedroom, with a camp bed, a desk with gems, coins, bronzes, a cabinet with decorations and medals, and by the window cases containing “thousands of casts of gems,” or in other words the dactyliothecae. All of this material is referred to as “objects for [Thorvaldsen’s] daily studies.” The walls in this intimate space were decorated with drawings that Thorvaldsen and Koch made after the German artist Asmus Jacob Carstens (1754–1798), and above the bed was “a small hand drawing by Raphael”. [31]XXXI A storage room on the staircase for plaster casts, marble, and terracotta was so packed that it was only just possible to enter it sideways.

Dactyliotheca with casts of 200 carved stones and pastes

(artworks, Roman architecture, portraits, etc.), 1830s.

Plaster, box: 7×2.2×32 cm. Inv. no. G140.

Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen.

Despite only covering a short period, Seidler and Thiele’s memoirs paint a useful picture. They reveal that Thorvaldsen’s home functioned both as a study for sketching and as a storeroom for his voluminous collections, as a result of which by late 1810 it had become virtually impossible to move around inside his home. Some years later he was able to separate the different functions into several rooms, but he still lived surrounded by his expanding collections. Thorvaldsen’s “motley mess” and unceremonious way of using his collections form an interesting contrast to their meticulous presentation at Thorvaldsen’s Museum, which is devoid of any sense of their former life in the artist’s apartment. It is also interesting that most of the works to which he gave a special place are not exhibited today. The attribution of the Madonna above the bed to Raphael could not be verified, and like the drawings inspired by his role model Carstens and the lithographs based on the Boisserée collection, it is not on permanent display. Perhaps this could be explained by these works on paper being delicate, but when a robust work such as Stieler’s portrait of the German heir apparent (who was later to become Ludwig I) is also hidden from view, the explanation could also lie in an attempt to link Thorvaldsen more closely to Denmark. When the dactyliothecae also fail to see the light of day, the previously mentioned concerns about originality might have also played a role.

Formerly attributed to Raphael. Mary and

Child, date unknown. Black chalk on paper,

53×40.5 cm. Inv. no. D461. Thorvaldsen’s

Museum, Copenhagen.

Echoes of the Rapture of Hylas

With the impressions of Thorvaldsen’s apartment in mind, we can imagine him hunting through his stockpile of motifs when conceiving a new work, and sketching it on paper or modeling it in wet clay from his tub. A closer analysis of a motif that he used in two different reliefs, Hylas and the Water Nymphs (1832 and 1833), can help us to understand the relationship between Thorvaldsen’s collections and his art. The story of the rapture of the beautiful youth Hylas by water nymphs is actually linked to the legend of Jason. Prior to his victorious return, losses and detours are encountered on the journey of the Greek hero Jason to the Black Sea in his quest to find the Golden Fleece — Hylas is one of those lost en route. It is after the first stretch on the Aegean when the fifty Argonauts have pitched camp and Hylas goes to fetch water that ill fortune strikes. The episode is recounted in Ancient Greek literature, including being an independent theme of the thirteenth idyll in the poet Theocritus’s (third-century BC) Idylls, and in the author Apollonius of Rhodes’s (third-century BC) epic poem The Argonautica. Thorvaldsen owned both of these literary works. In Theocritus, the abduction of Hylas is the subject of a short, hexametrical poem. The culmination is the seduction: on a slope of flowering bushes and twining bindweed, Hylas finds a spring for water, but this is where the nymphs lie singing:

Malis, and young Nychea looking spring,

And fresh Eunica. There the youth did bring,

And o’er the water hold his goodly urn,

Eager at once to dip it and return.

The Nymphs all clasped his hand; for love seized all,

Love for the Argive boy; and he did fall

Plumping at once into the water dark [32]XXXII

When Hylas lowers his jar, all three nymphs grab his hand and drag him into the water. In The Argonautica the scene is slightly different. Hylas arrives at the spring as the nymphs gather to worship Artemis, but here only one of the nymphs, Ephydatia, notices the beautiful young man in the light of the full moon:

As soon as, stooping to receive the tide,

He to the stream his brazen urn apply’d,

In gush’d the foaming waves; the nymph with joy

Sprung from the deep to kiss the charming boy.

Her left arm round his lovely neck she threw,

And with her right hand to the bottom drew. [33]XXXIII

In this version a single nymph throws her left arm around Hylas’s neck to kiss him, pulling him into the water with her right hand. Thorvaldsen owned the writings of Theocritus in Latin, Theocriti reliquiae (1765), as well as Apollonius’s Argonautica in Italian (1791–94), and was probably familiar with the passages about Hylas. It also looks as if two representations of Hylas in his collections echo the literary works. One of them is a work on paper from his own lifetime: a landscape drawing attributed to his friend Joseph Anton Koch. The other is a plaster cast of a (presumably) Roman well-head called Fagan’s Puteal. In both works the abduction is an independent subject in the spirit of Theocritus, and Hylas’s encounter with several water nymphs is similarly in keeping with Theocritus. However, that a single nymph lays her hand on the neck of Hylas in order to kiss him is apparently taken from Apollonius. Thorvaldsen continued this double inspiration.

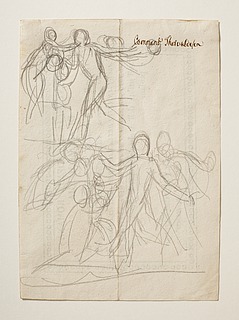

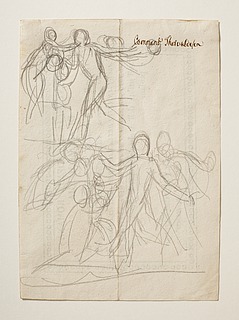

Bertel Thorvaldsen. Sketch for Hylas and the Water Nymphs,

1811–13. Pencil, pen, and ink on paper, 8.2/11.3×18.6 cm.

Inv. no. C377. Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen.

Ten preserved sketches by Thorvaldsen reveal that he considered three different representations of the scene, firstly with a half-upright Hylas figure, secondly with a kneeling Hylas figure, and thirdly with a standing Hylas figure, each of them closely surrounded by nymphs. Five of the sketches depict the young man in the characteristic position of standing with one leg on the ground and the other kneeling on a rock as he raises his arm in defense or as an invocation. This posture is familiar from several works from antiquity, including an opus sectile mosaic from the Junius Bassus basilica in Rome (331 BC). Thorvaldsen must have seen a version of this, but did not pursue it.

Four of the sketches show Hylas kneeling. One of them depicts turbulent close combat, where three demonic looking nymphs grab at Hylas.

Bertel Thorvaldsen. Sketch for Hylas and the Water Nymphs,

after 1797. Charcoal on paper, 20.9×32.6 cm. Inv. no. C379.

Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen.

However, in Thorvaldsen’s marble relief from 1832, the kneeling figure of Hylas rather looks taken by surprise. He is on one knee on the riverbank as a nymph emerges from the water before him, who places one arm around his shoulder as the other hand holds his chin as if preempting a kiss. Behind her another nymph rushes towards him with open arms, while a third watches from the water, fascinated. Hylas raises one arm to keep his balance, but spills the water from his jar as he fails to do so. “[H]is fall is inevitable,” as the author Jensen writes in a rare analysis of the relief: “[H]e fights in vain to regain his balance.” [34]XXXIV

Bertel Thorvaldsen. Hylas and the Water Nymphs, 1832.

Marble, 40.7×76 cm. Inv. no. A482.

Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen.

Attributed to Joseph Anton Koch. Hylas and the Water

Nymphs (descriptive title), date unknown. Black and

brown ink on paper, 14.4×19.1 cm. Inv. no. D1837.

Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen.

The kneeling Hylas with his raised yet powerless arm is very similar to the figure in the landscape attributed to Koch, just laterally reversed, which suggests that Thorvaldsen was inspired by Koch. Here, I would venture the claim that the sketch was actually made by Koch. I base this on the fact that the abduction scene does not dominate the landscape, and that small, dramatic scenes in large, idyllic landscapes are typical of Koch. [35]XXXV Koch’s kneeling Hylas is, however, itself an echo. Many years previously he had made twenty-four etchings based on Asmus Jacob Carstens’s Les Argonautes (1799), and it looks as if Carstens’s kneeling Hylas was also the source of Koch’s own Hylas works. [36]XXXVI The motif could easily have more precedents and a much longer history.

Thorvaldsen’s depiction of Hylas standing is apparently roughly based on Fagan’s Puteal. In the marble relief Hylas and the Water Nymphs from 1833, the figure of Hylas is standing in a stylized landscape but is assailed by avid nymphs on all sides. A running nymph lays her arms on his arm and just reaches his chin, another nymph kneels and grasps his calf, and a nymph sitting behind him fills his jar as she buries her fingers in his curls.

Bertel Thorvaldsen. Hylas and the Water Nymphs, 1833.

Marble, 68×109.5 cm. Inv. no. A484.

Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen.

Cast of well-head titled Fagan’s puteal after its

finder, British archeologist Robert Fagan (circa

1761–1816). Hylas and the Water Nymphs together

with Narcissus and Echo (opposite side), presum-

ably Roman, however this cannot be determined

as the original has been lost. Plaster, 81×67 cm.

Inv. no. L298. Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen.

On the well-head, Hylas is also depicted upright, holding his jug surrounded by three nymphs. One nymph is holding his lower arm, another emerges from the water in front of him and grasps his thigh, and a third regards him from a distance. Thorvaldsen’s relief can be seen as an obvious, laterally reversed interpretative repetition of this representation. However, it is just as evident that he made the motif his own. Unlike the image on the well-head, Hylas’s fall is inscribed in the insecure foothold of the figure: in Thorvaldsen’s work one of his feet is already hovering above the water. This instability is also present in a preliminary sketch in which Thorvaldsen experimented with a standing figure of Hylas. At the same time, he replaced the bent trees and circling waves on the puteal with a more stylized, toned-down landscape while conveying both inner and outer turmoil through the animated robes of the figures.

Thorvaldsen’s work on the Hylas motif is practically a demonstration of the phenomenon at the heart of Aby Warburg’s (1866–1929) research – the afterlife of Antiquity in later periods. In a short lecture from 1905, Warburg uses Albrecht Dürer’s (1471–1528) drawing The Death of Orpheus (1494), in which Orpheus is forced to his knees using one arm to resist the attack of armed maenads, to demonstrate the return and recurrence of the idioms of Antiquity. [37]XXXVII Dürer borrowed the image from an engraving by one of Andrea Mantegna’s (1431–1506) students, who had found the motif in Roman Antiquity, which in turn echoes Greek Antiquity. The emotionally charged representation of the body, which proves so popular that artists from several periods repeat it, is something Warburg invented an important concept for, i.e. the “emotive formula” (Pathosformel). [38]XXXVIII He also delivers a politely formulated yet sharp criticism: according to Warburg the doctrine of “quiet grandeur” had become so entrenched that the fact that Renaissance artists turned not only to the idealized tranquility of Antiquity, but also borrowed its emotional expressiveness, had been overlooked.

With Warburg as guide, something similar could be claimed of Thorvaldsen_that he too drew on the emotional expressiveness of Antiquity instead of being solely inspired by the “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur” advocated by Winckelmann. The Hylas reliefs are a perfect example of Thorvaldsen using an “emotive formula” (Pathosformel) of the more Dionysian side of Antiquity. Turning to Warburg, we can also counter views that reduce the recycling of motifs to uninspired imitation. Dürer, Warburg writes, was mentally open to the motif, but also encountered it with instinctive resistance and supplied it with equanimity. Here, repetition expresses the capacity to be open to a motif of Antiquity and make it one’s own. [39]XXXIX As illustrated above, for Thorvaldsen the recycling of a motif also went hand in hand with its artistic transformation.

Bertel Thorvaldsen. Sketch for Hylas and

the Water Nymphs, 1832. Pencil on paper,

inscription in pen, 20×14.2 cm. Inv. no.

C372r. Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen.

Conclusion

In the preceding pages, Thorvaldsen’s collections have been defined by their vast complexity and are seen to be governed by principles that match advice given by Winckelmann, who recommended the accumulation of a “stock of erudition.” At the same time, I have suggested that the presentation of the collections was influenced by a desire to paint an uncontroversial picture of Thorvaldsen as a collector and artist. There was apparently concern that the artist’s popularity with the public would be diminished if his art and collections were firstly not seen to meet contemporary sexual mores in Denmark, secondly, were perceived as being too far removed from a Danish-Nordic horizon, or thirdly, appeared to be too closely related. To connect with the meaning the collections had for Thorvaldsen, an attempt has been made to visualize their presence in his Rome home. In the memoirs of others, his apartment emerges as a workstation for the initial stages of his sculptures, as well as a storage space for his collections. Thorvaldsen lived in the midst of his collections, and had an active relationship to them. Using the two reliefs Hylas and the Water Nymphs as examples, I have pointed out how he might have used his collections as a reservoir of motifs. For the Hylas reliefs he experimented with three different representations, and the two he ended up with bear close resemblance to representations of the theme in his collections. Thus, Thorvaldsen used existing representations that could be called “emotive formulas,” using Warburg’s term, but he made them entirely his own.

My attempt to re-establish a connection between Thorvaldsen the collector and Thorvaldsen the artist ends with the conclusion that seems to have been avoided in the mid-eighteen hundreds: that his collections and art have an erotic vein; that his Danish and Nordic identity is not a key feature of his oeuvre; and that he did not always create motifs inspired by Antiquity from scratch, but also borrowed happily, including from his own collections. This was certainly also evident to those who wanted to tone this down in the eighteen hundreds, something they managed so effectively that it remains an important task to expose the collector and artist Thorvaldsen without this filter.

Commentaries

Last updated 03.07.2018

Letter to Thorvaldsen from Nicolo Corrado de Lunzi, June 30, 1836, the Thorvaldsen’s Museum Archives.

Poul Fossing, The Thorvaldsen Museum Catalogue of the Antique Engraved Gems and Cameos (Copenhagen and London, 1929), p. 13.

Unpublished exhibition list by Torben Melander for gallery thirty-nine at Thorvaldsen’s Museum.

Kristine Bøggild Johannsen, “Relics of a Friendship,” in Karen Ascani et al., eds., The Forgotten Scholar: Georg Zoëga (1755–1809) (Leiden and Boston, 2015), pp. 31–32.

Letter to Thorvaldsen from Ditlev Martens, January 28, 1834, The Thorvaldsen’s Museum Archives.

Kira Kofoed, “Thorvaldsen’s Collection of Paintings—a Collection with a Significant Lack,” 2015, The Thorvaldsen’s Museum Archives.

Jan Zahle, Thorvaldsens afstøbninger efter antikken og renæssancen (Copenhagen, 2012), pp. 40–41.

Ibid., pp. 16–17.

Ibid., pp. 88–91 and 111–12.

Jane Fejfer and Torben Melander, Thorvaldsen’s Ancient Sculptures (Copenhagen, 2003), p. 19.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, “Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and the Art of Sculpture,” in Johann Joachim Winckelmann on Art, Architecture, and Archaeology, trans., David Carter,

(Suffolk and Rochester, 2013), p. 53

Meïr Aron Goldschmidt, “Thorvaldsens og Oehlenschlægers Levnetsbeskrivelser,” Nord og Syd (1851), pp. 138–39.

Torben Melander, 2 + 1. Antikke smykker, lamper og masker i Thorvaldsens Museum (Copenhagen, 2006), p. 53.

Ibid., p. 56.

Nanna Kronberg Frederiksen’s important exhibition Liberty, Equality, and Desire! at Thorvaldsen’s Museum (2015–17) included many otherwise censored objects as part of the exhibition’s exploration of Thorvaldsen’s philosophy of love. The first time a selection of the erotic antiquities was on display was in 1983. See Torben Melander, Antik erotisk kunst fra Thorvaldsens samlinger, (Copenhagen, 1983).

Zahle 2012 (see note 7), p. 32.

Kira Kofoed, “Norse Mythology in Thorvaldsen’s Art—a Virtually Omitted Motif,” 2014, The Thorvaldsen’s Museum Archives.

Karen Benedicte Busk-Jepsen, “At Home in Rome,” 2015, The Thorvaldsen’s Museum Archives.

Karen Benedicte Busk-Jepsen, “At Home in Rome,” 2015, The Thorvaldsen’s Museum Archives.

Johannes V. Jensen, “Thorvaldsens Fristelser,” Dansk Land (1928), p. 8.

Julius Lange, Sergel og Thorvaldsen, (Copenhagen, 1886), p. 136ff.

Ibid., p. 220.

Jørgen Birkedal Hartmann, Antike Motive bei Thorvaldsen (Tübingen, 1979) deals specifically with Thorvaldsen’s revival of antique motifs. Since then, the phenomenon has been given important examples in, for instance, Torben Melander, Thorvaldsens antikker (Copenhagen, 1993) and Zahle 2012 (see note 7).

Frederik Christian Hillerup, Italica eller Mindeblomster fra mit Ophold i Italien (Copenhagen, 1829), pp. 96–97.

Louise Seidler, Erinnerungen und Leben der Malerin Louise Seidler, in H. Uhde, ed., (Berlin, 1874), pp. 223–24. The three other inhabitants that Seidler mentions are the German artists “Schadow,” meaning Rudolf (1786–1822) or his brother Wilhelm (1788–1862), Adolf Senff (1785–1863), and Karl Wilhelm Wach (1787–1845). Seidler travelled to Rome at the end of October 1818, and Wach moved in June 1819, so her observations must have been made between October 1818 and June 1819.

Seidler 1874 (see note 25), pp. 223–24.

Just Mathias Thiele, Den danske Billedhugger Bertel Thorvaldsen og hans Værker, vol. 2 (Copenhagen,

1832), p. 124.

Ibid., p. 125.

Die Sammlung Alt-Nieder- und Ober-Deutscher Gemälde der Brüder Sulpiz und Melchior Boisserée und Johann Bertram, lithographiert von J.N. Strixner (Stuttgart, 1821–34). Thorvaldsen subscribed to the lithographs of the Boisserée collection and presumably replaced the images in his frames with new ones, each time he received a new shipment. This gives an impression of Thorvaldsen as a modern consumer of images in the light of new techniques of reproduction.

Thiele 1832 (see note 27), p. 126.

Ibid., p. 127.

The Idylls of Theocritus, Bion, and Moschus, and the War-Songs of Tyrtaeus, trans. J. Banks and M. J. Chapman (London, 1870), pp. 242–43.

The Argonautics of Apollonius Rhodius, trans. Francis Fawkes (London, 1780), p. 69.

Jensen 1928 (see note 20), p. 8.

Also, Koch’s drawing seems to be a preliminary study for his painting Landscape with the Abduction

of Hylas (1832), now held by Städel Museum, Frankfurt. This painting could also have served as a source of inspiration for Thorvaldsen, since here even the nymphs are in the same position as in Thorvaldsen’s work, and Koch mentions his interest in it in a letter. Letter to Thorvaldsen from Joseph Anton Koch dated April 18, 1833, The Thorvaldsen’s Museum Archives.

Markus Neuwirth, Die Argonauten (Graz, 1989), pp. 42–43.

Aby Warburg, “Dürer and Italian Antiquity,” The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity, trans. David Britt (Los Angeles, 1999), pp. 553–58.

Ibid., p. 555.

Ibid., p. 556.