Flora Italica. When an Italian Flowery Meadow Visited Thorvaldsens Museum

- Karen Benedicte Busk-Jepsen, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2019

- Translation by Andrew D. Jackson, Karen Jelved

This essay was originally published (in Danish) in the review PERISKOP. Forum for kunsthistorisk debat, nr. 22, 2019, pp. 124-133

Countless myths surround Bertel Thorvaldsen. One of the most persistent ones tells that the sculptor inadvertently introduced the giant hogweed from Italy when his sculptures were shipped to Denmark – because the beautiful, but poisonous and later so unwelcome, umbellifer had been used as wrapping in the transportation crates. In reality, the giant hogweed was introduced by the Botanical Garden and cultivated as an ornamental plant on the grounds behind Charlottenborg Palace as early as around 1803 – and it had not been imported from Southern Europe but from the Caucasus (Vestergård 2007, 410). (1) In other words, the story that Thorvaldsen introduced the giant hogweed to Denmark is as dubious as the anecdote that he was born on a ship between Reykjavik and Copenhagen – or the extravagant fabrication that he was lineally descended from three legendary Norse kings (David d’Angers 1856, 4; Magnússon 1829). (2) Still, the story about the giant hogweed does contain an element of truth – just as the message in a game of Chinese whispers is gradually distorted as it is passed on but still contains parts of what was originally said. Once you remove the giant hogweed from the equation, it is true that Thorvaldsen’s art was wrapped in plant material when it was shipped to Copenhagen, and it is also true that this vegetation took root in Denmark. However, reality surpasses the myth inasmuch as the stowaway in the crates was a highly diversified flora.

An Unexpected Addition to the Danish Flora

One has to imagine a wealth of plants that had never been seen on Danish soil before springing up on a building site in the centre of Copenhagen near the as yet unfinished Thorvaldsens Museum. Around the ochre yellow building that workers and artists were busy constructing and decorating after the drawings of the architect Michael Gottlieb Bindesbøll (1800-56), a small meadow of alien plants had sprouted. The experts of the time were fascinated, and the 27-year-old botanist Johan Lange (1818-98), who was to become director of the Botanical Garden and the editor of the final parts of the mammoth work Flora Danica, threw himself into the task of collecting, recording, and preserving the many exotic species.

In a short article from 1845, “An Unexpected Addition to the Danish Flora”, Lange explains the sensational phenomenon: During the unpacking of the crates with Thorvaldsen’s works of art, the hay which had been used to wrap the works in Rome, had been discarded on the site next to the museum – and this hay must have contained seeds that were able to sprout because they had been thrown on earth and gravel from the construction work. Lange lists 25 species of plants he had found flowering and several “as yet undetermined species” that had not blossomed, either because of the cooler climate or because they were “biennial plants” (Lange 1845, 137). More species were identified in the course of time. Notwithstanding, the Italian meadow was for many years overshadowed by the giant hogweed.

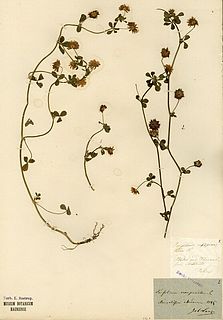

Herbarium sheet. Trifolium resupinatum (Shaftal Clover). Collected by J.M.C. Lange. Reproduced with the permission of the Museum of Natural History, University of Copenhagen.

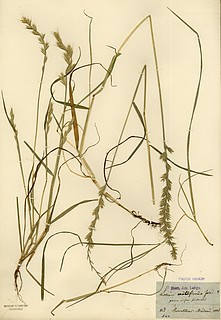

Herbarium sheet. Lolium multiflorum (Italian Rygrass). Collected by J.M.C. Lange. Reproduced with the permission of the Museum of Natural History, University of Copenhagen.

Oblivion and Rediscovery

The botanical phenomenon that took place near Thorvaldsens Museum about 175 years ago had been consigned to oblivion and was absent from the history of the museum until last year (2018), when a spontaneous interdisciplinary investigation gradually made the pieces of the puzzle fall into place. The American artist Crystal Bennes had started studying the topic after having seen a reference to it from the British writer Richard Mabey, and she visited both Thorvaldsens Museum and the Museum of Natural History in Copenhagen during her work on an article now printed in Migrant (Mabey 2010, 144; Bennes 2018). (3) In the former museum, which regularly has the job of refuting myths about the sculptor, the story about the Italian plants was met with automatic scepticism – but it soon became clear that it was a very well documented phenomenon. During a visit to the herbarium of the Museum of Natural History, where Bennes was assisted by the Swedish botanist Olof Ryding, she identified nine herbarium sheets produced by Lange with artistically mounted Italian plants purportedly found near Thorvaldsens Museum (Bennes 2018, 118). Suddenly the phenomenon was very real.

A few days later, another piece of evidence surfaced when Stig Miss, former director of Thorvaldsens Museum, located a musty plastic bag with hay in the basement of the museum: “Original packing material from return found in the torso 1999” [sic], as it says on a handwritten manila label attached to it. Olof Ryding promptly subjected the hay to a botanical analysis, and after an obligatory freezing to minus 40 degrees, he extracted seeds and fruits from it. It was possible to confirm that the hay was Southern European, and that it had to be a small portion of original packing hay – which seems to have survived inside a sculpture. Which one is not known with certainty, but several things seem to indicate that it was Thorvaldsen’s plaster cast of the antique fragment The Belvedere Torso. (4) However that may be, the hay proved to be unusually rich in species. So far, Ryding has found seeds, fruits, and fragments in it from about 60 species.

As mentioned above, the hay was a stowaway on the ships that transported Thorvaldsen’s works and collections to Thorvaldsens Museum between 1833 and 1845. (5) The springy material was packed tightly around the objects in their crates in order to keep them in place and protect them from bumps and jolts on the long voyage. Thus protected before transportation, the works could be launched in the Tiber in smaller boats and sailed 300 kilometres north to the port of Leghorn in Toscana, where they were loaded onto a bigger ship heading for Copenhagen. The small pile of hay nestling inside the “torso” until today and the hay that had been dropped outside the museum in the 1840s probably came with two different shipments out of a total of seven. If the little pile of hay did indeed nestle inside The Belvedere Torso, then it must have been part of the packing of Thorvaldsen’s collection of casts that was transported to Copenhagen in 1839, while the hay that transformed into the meadow in 1845 – which, according to Lange, had come with “the most recently arrived” works – came to the museum with one of the last shipments in 1844 or 1845 (Lange 1845, 137). (6) This is consistent with the fact that the species in the pile of hay and on the herbarium sheets are not completely identical.

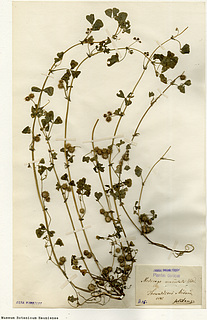

An impediment to the rediscovery of the self-sown meadow was that the herbarium sheets with plant species found near Thorvaldsens Museum had been separated in the herbarium at the Museum of Natural History, i.e. classified according to species rather than finding place. However, since Bennes initiated the search and the first nine sheets were found, Ryding has discovered many more so that more than 80 sheets with 29 different species have been identified, i.e. four more species than in Lange’s article from 1845. Among these are many species of pea-flower and grass families but also of mallow and honeysuckle families and others. The strangely beautiful plant mountings testify to the long botanical tradition of combining the true with the aesthetically pleasing – even when it comes to mounting weeds on cardboard – and of great consideration for rare plants.

In Search of a Shaftal Clover

The question naturally arises whether any of the 29 visiting species settled permanently in Denmark. An exhaustive answer cannot be given here, but the herbarium sheets that are reproduced in these pages show four of the species that seem to have survived at least for a time. Already in 1845, Lange discussed the possibility that the plants could survive:

As several of the species mentioned here have borne ripe seeds in abundance, it seems reasonable that these will survive in the place where they grow, also in the years to come, and many of them may spread further once the earth on the site is carted away. (Lange 1845, 138)

The botanist was right as some of the herbarium sheets show plants gathered near the museum as late as 1848. But what happened to them when the heaps of earth were carted away before the opening of the museum in September 1848? Six years later, Lange reached the disappointing conclusion that “the great many Italian plants” had now all “disappeared” except for two species, Trifolium resupinatum (Shaftal Clover) and Medicago maculata (Spotted Medick), which the botanist J.S.D. Branth had found on Amager (Lange 1854, 39). However, the continued life of the plants is a serial in many instalments, which a few references in the botanical literature can illustrate. In Handbook in the Danish Flora a few years later, Lange himself mentions that a third species, Valerianella eriocarpa (Italian Corn Salad), had strayed into Rosendal’s Garden on Østerbro and adds enthusiastically “and earlier on the site near Thorvaldsen’s Museum!” (Lange 1856-59, 30). In 1872, the botanist Hans Mortensen (1825-1908) added yet another species to the one mentioned above, Malva Nicaeensis (French Mallow), which, together with Trifolium resupinatum (Shaftal Clover), “strangely enough both have been found on Amager near Kastrupmølle” (Mortensen 1872, 43). That several species from the museum were prevalent on the island of Amager can be explained by the fact that the earth was dumped out there. Thus, it was also on Amager that a Medicago hispida Gaertner (Burr Medick) was found in 1891 (Lange 1895-96, 285). A closer study of the botanical literature of the time may lend further credibility to the Amager hypothesis and, most probably, reveal more finds of exotic species.

The writer Sophus Bauditz’ burlesque Copenhagen novel Absalon’s Well (1901) provides evidence that not only botanists were interested in the fate of the Italian plants. Here, the botanical enthusiast and schoolteacher Berner recognizes a withered Trifolium resupinatum (Shaftal Clover) in the young girl Marie’s sash but his friend, a bookseller from Jutland, does not understand the significance of his finding: “Dear me, Terndrup, I am certain I already told you about that: The foreign clover that once appeared on the site near Thorvaldsens Museum but now has been gone for a long time” (Bauditz 1901, 31-33). Throughout the novel, the schoolteacher dreams of finding the rare species of clover in the merchant’s yard, where Marie’s childhood sweetheart picked it. However, when he succeeds many years later, the clover has become such an embarrassing subject in the relation between Marie and Poul, the merchant’s son, that Berner must desist from announcing his find so that they can get married (Bauditz 1901, 411-23).

In spite of the legendary status of the Italian plants more than half a century after they sprouted, they faded from memory, even at Thorvaldsens Museum. On the other hand, they seem never to have been forgotten by botanists. Recently, the botanist Per Hartvig wrote a short paragraph on the matter in Atlas Flora Danica (2015). Here he writes about the so-called adventive species near Thorvaldsens Museum that many of them are no longer found in Denmark, “but at least 10 species in our contemporary flora were then found to be new to the country” (Hartvig 2015, 218). This, however, does not mean that the ten species in the present vegetation are necessarily descendants of the plants near the museum as the species could have come to the country in countless other ways since then. A species like Lolium multiflorum (Italian Ryegrass) was already naturalized about three decades after it was first seen in Denmark near Thorvaldsens Museum, but there were also attempts to grow it as a crop from the 1840s (Jensen and Lind 1922-23, 326-27). (7)

Herbarium sheet. Medicago arabica, also called Medicago maculata (Spotted Medick). Collected by J.M.C. Lange. Reproduced with the permission of the Museum of Natural History, University of Copenhagen.

Herbarium sheet. Valerianella eriocarpa (Italian Corn Salad). Collected by J.M.C. Lange. Reproduced with the permission of the Museum of Natural History, University of Copenhagen.

The Naturalization of Adventive Plants

As early as 1845, Lange wondered whether it would be possible to include the Italian species in the official Danish flora if they became widespread – and he did not think that they could be “denied citizenship” if that happened.

If some of them were distributed widely enough that the question would arise in the future as to whether to include them in the register of Danish plants, then one would probably not deny them citizenship because one happened to know the way in which they arrived here, given that one lists as Danish many other plants growing wild around the towns, in seeds, etc., e.g. the corn cockle, the cornflower, and others which were undoubtedly introduced in the past even though it is generally not possible to determine the time when they immigrated or the place from where they came. (Lange 1845, 138)

Thus, the botanist describes it as a given that adventive plants continuously naturalize and pass into the Danish flora – which is why it would not be possible to deny the Italian plants citizenship if they stayed in Denmark. The argument is purely botanical, of course, but in Lange’s humorous anthropomorphism of plants there may also be a sly reference to the public debate of the time, when the tendency to discriminate between Danish and foreign was growing.

Thorvaldsen himself is an interesting case when the catchwords are citizenship and migration. He transplanted himself to Rome at the age of 27, and although, according to the rules of the Academy of Arts, he was under a strict obligation to return to Denmark and serve his King and his Country when his scholarship expired in 1802, he stayed even at the risk of losing his citizenship (Bencard, 2009). In Rome he became a central figure in a cosmopolitan circle of artists, which the writer Carsten Hauch (1790-1872) described in the following way: “… if you just agreed about art, no-one asked what country you were born in” (Hauch 1871, 218). Thorvaldsen subscribed both artistically and politically to international currents. In his art he embraced the aestheticism and motifs of antiquity, and “in politics he was as radical as they come”, as the German painter Wilhelm Schadow (1788-1862) wrote (Brandes 1920, 21). The sculptor sympathized with the universalistic ideals of the French Revolution, and in their favourite haunt Caffè Greco he applauded inflammatory revolutionary speeches “à la [Arnold] Ruge and [Ludwig] Feuerbach” (Brandes 1920, 21).

Therefore, it is interesting to see how Thorvaldsen was approached when the national rearmament in Denmark increased. Given his clear international orientation, the sculptor’s attitude was completely different from that of the great agitator of national romanticism, the art historian N.L. Høyen (1798-1870), who wanted young artists to become patriots and “prepare themselves” on “Denmark’s isles and plains” (Høyen 1844, 12). Nonetheless, many, including Høyen himself, shared the wish that Thorvaldsen, being an equilibristic artist and an international star, would contribute to the national project. Some tried to persuade him to join the cause – like Adam Oehlenschläger (1779-1850), who called on him to think “of the band of the old Norse gods, of the first glorious ideas of a people from whom you descend!” and to portray Norse gods (Oehlenschläger 1819; Kofoed 2014). His exhortations had no effect.

Others were so eager to repatriate Thorvaldsen, so to speak, that they conjured up a kind of proto-Norse artist persona. As mentioned above, they fabricated a genealogical table showing his descent from three legendary Norse kings, and they spread the story that he had been born on a ship between Reykjavik and Copenhagen. These are just two examples of the mythmaking intended to root Thorvaldsen as deeply as possible in Danish/Norse soil. That time was long gone when his continuance in Rome had almost cost him his Danish citizenship. As is well known, the sculptor ended up bequeathing his life’s work to Copenhagen. After repeated requests, he returned to Denmark in 1838 and was welcomed as a national hero. However, a few years later, in 1841-42, he went back to Rome, and he was meant to have visited there again the year he died.

Symbolic and Real Flora

While an Italian flowery meadow surrounded Thorvaldsens Museum in the summers between 1845 and 1848, several artists were painting a symbolic flora in the inner courtyard of the museum. Here, the sculptor, who died in Copenhagen in 1844, was to be interred. The decoration of the courtyard evokes a kind of memorial garden with a trellis-work of symbolic trees: laurels, oaks, and palms. On the other hand, one finds no lemon trees or cypresses on the walls – let alone the towering pines that define the Roman skyline.

In the middle of the courtyard, a raised, rectangular bed of roses marks Thorvaldsen’s grave. Under it, the sky-blue walls of the burial chamber are decorated with white lilies and red roses so that when the sculptor’s coffin was lowered into it in 1848, four years after his death, he was laid to rest in the middle of an Elysian flowerbed, where the symbolism of the plants speaks of purity and love. It is all very beautiful, but it is also thought-provoking that the museum had been surrounded by a living, wild field flora from Italy for several years. Opposite the controlled and contained representation of Thorvaldsen’s Danish legacy, the Italian flowery meadow was and is a wonderfully unpredictable and tangible greeting from Thorvaldsen’s second homeland. Elucidation of the phenomenon continues. And not a word about the giant hogweed.

References

Sophus Bauditz: Absalons brønd, Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag, Copenhagen 1901

Crystal Bennes: “Thorvaldsen’s Weeds”, Migrant 5, 2018, pp. 112-121

Ernst Jonas Bencard: “Thorvaldsens forbliven i Rom omkring 1803-1804” arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk 2009

Georg Brandes: “Thorvaldsen og nogle Kvinder”, Tilskueren, Copenhagen 1920

Pierre-Jean David d’Angers: Lettre sur Thorwaldsen, Poulet-Malassis et De Broise, Alençon 1856

Nanna Kronberg Frederiksen: “Thorvaldsens bolig, værksted og museum på Kunstakademiet”, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk 2014

Geoffrey Grigson: Gardenage or the Plants of Ninhursaga, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1952

Per Hartvig: Atlas Flora Danica 1-3. Gyldendal, Copenhagen 2015

Carsten Hauch: Minder fra min første Udenlandsreise, C.A. Reitzels Forlag, Copenhagen 1871

N.L. Høyen: “Om Betingelserne for en skandinavisk Nationalkonst’s Udvikling”, C.A. Reitzel, Copenhagen 1844

Knud Jensen og Jens Lind: “Det danske Markukrudts Historie”, Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskabs Skrifter 8, 1922-23, pp. 1-496

Kira Kofoed: “Nordisk mytologi i Thorvaldsens kunst – et så godt som udeladt motiv.” arkivet.thorvaldsens-museum.dk 2014

Johan Lange: “En uventet Tilvæxt til den danske Flora”, Dansk Ugeskrift 190, 1845, pp. 137-138

Johan Lange: Haandbog i Den Danske Flora, C.A.Reitzels Forlag, Copenhagen 1856-1859

Johan Lange: “Nogle Exempler paa Planters Acclimatisation”, Videnskabelige Meddelelser fra den naturhistoriske Forening i Kjöbenhavn 6, 1854, pp. 37-48

Johan Lange: “Oversigt over de i nyere Tid til Danmark indvandrede Planter”, Botanisk Tidsskrift 20, 1895-1896, pp. 240-287

Richard Mabey: Weeds: The Story of Outlaw Plants, Profile Books, London 2010

Finnur Magnússon: “Brudstykker af Thorvaldsens Stamtavle”, Arkivet, Thorvaldsens Museum, Thieles Excerpter, 1829

Hans Mortensen: “Nordostsjællands Flora”, Botanisk Tidsskrift 5, 1872, pp. 8-168

Adam Oehlenschläger: Tale i Anledning af Thorvaldsens Hiemkomst til Fædrelandet, Forfatterens Forlag, København 1819

Frederik Schmidt: Dagbogsnotat fra 10.10.1818, Arkivet, Thorvaldsens Museum, ea9323

Peter Vestergård: Naturen i Danmark, Gyldendal, Copenhagen 2007

Thanks to:

Crystal Bennes, Ernst Jonas Bencard, Nanna Kronberg Frederiksen, Charlotte Hauch, Kristine Bøggild Johannsen, Kira Kofoed, Stig Miss og Olof Ryding.

Last updated 17.09.2020