Milan in Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Times

- Chiara Battezzati, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2021

Artiklen er ét ud af i alt to foredrag, der blev holdt på Thorvaldsens Museum i forbindelse med særudstillingen «Længsler: Thorvaldsens italienske malerier» under titlen Milan and Pinacoteca di Brera in Bertel Thorvaldsen’s time, d. 7. oktober 2021. Artiklen af Elisabetta Bianchi, der udgjorde det andet foredrag, kan læses her.

In 1811, Bertel Thorvaldsen was appointed an honorary member of the Academy of Fine Arts in Milan, a city he visited several times in the years up to 1841.

In Milan, and more generally in the Lombardy region, Thorvaldsen could always rely on important collectors and patrons such as Paolo Tosio of Brescia who, in his extraordinary collection of ancient and modern works of art, included marbles such as the Ganymede with Jupiter’s Eagle. His collection provided the very core of the Civic Art Gallery of Brescia, which is called the Tosio Martinengo Picture Gallery. Furthermore, Thorvaldsen’s patrons were the Milanese nobleman Giovanni Edoardo de Pecis who, in 1827, donated his magnificent collection to the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan with five marbles by Thorvaldsen; and the German banker Heinrich Mylius, originally from Frankfurt am Main, who wanted to build a small temple dedicated to his son’s memory in the garden of his villa in Loveno di Menaggio, on Lake Como, decorated with the stunning bas-relief by Thorvaldsen – the Nemesis attended by the genii of punishment. Thorvaldsen could also rely on the very rich and powerful Giovanni Battista Sommariva. Sommariva was a great collector and a distinguished patron – who had an obsession for Antonio Canova – but collected works of his rival Thorvaldsen too, such as the Triumph of Alexander, which was first designed for Napoleon and is a true masterpiece of the Danish sculptor: it is still kept in Sommariva’s villa on Lake Como (nowadays known as Villa Carlotta).

What was Milan like in the first half of the 19th century? For what purpose would a foreign artist or traveller come to the city? And what kind of art could they find inspiring?

Over the centuries of the Grand Tour, Milan was essentially just a city on the road to reach the most coveted and desired destinations, in the search of something more exotic and “Italian”. For a traveller coming from Northern Europe, Venice, Florence, Rome and the sun of the South were certainly of greater appeal. However, although it could not claim the artistic treasures of other Italian cities, many travellers found Milan pleasant and welcoming: one above all, the French writer Stendhal who was so fond of the city and its inhabitants that he defined himself as “Milanese”.

Then as today, Milan was one of the most important cities in Italy, a nation that did not yet exist as a country as it was not united at that time; instead, it was divided into many regional states, similarly to Germany. Italy would be united only in 1861. As a matter of fact, in the first half of the 19th century, Milan has been a French and Austrian city, but it was in any case the most important and modern city in Northern Italy. At the end of the 18th century, under Austrian rule, Milan had been the cradle of Lombard Enlightenment: as an example, it was the Milanese Cesare Beccaria who in 1764 published the treatise On crimes and punishments in which he demonstrated the ineffectiveness of torture and death penalty in the prevention of crimes: it was the first case in Italy of such innovative thoughts. In the same years, one of the symbols of the city was built: Teatro alla Scala, the temple of opera by the architect Giuseppe Piermarini, which during the 19th century has been the stage of the success of Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti and, especially, Giuseppe Verdi.

01. Alessandro Sidoli, Johann Jakob Falkeisen, Teatro alla Scala in Milan, engraving, 1836-1838 ca., Milan, Civiche Raccolte Storiche, Palazzo Morando | Costume Moda Immagine, vedute 36

After the French invasion of 1796, Milan became a French city. In 1805, after some ups and downs, Milan became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy: Napoleon was crowned king of Italy in the Duomo. In this very moment, a very lively period opened up for Milan: Andrea Appiani was appointed as Napoleon’s first painter, the artist and scholar Giuseppe Bossi animated the Brera Academy and the city cultural stage, the Brera Picture Gallery was founded and the city was redesigned by architects. Just to give a few examples: in the very centre of the city, just a few steps away from the Cathedral and the Castle, the architect Giovanni Antonio Antolini conceived the project for the Bonaparte forum to provide the capital with a brand new civil, administrative, political and economic centre. While the Bonaparte forum remained at a project stage, the fortifications around the ancient Sforza Castle were instead demolished, the Simplon road towards France was opened, starting with the city street which still exists.

02. Celebrations for the Treaty of Lunéville and laying of the first stone for the Bonaparte forum, drawing, 1801, Milan, Civiche Raccolte Storiche, Palazzo Morando | Costume Moda Immagine, inv. 837.

Nowadays, what’s left to certify this fervor are the Arena by Luigi Canonica, built in 1806, and the monument known today as Arco della Pace (Arch of the Peace) by Luigi Cagnola. The building of this Arch started in 1807 to celebrate the Napoleonic victories but ended only after the return of the Austrians and afterwards named in homage to Peace.

The entry of the Austrians in Milan, April 1814, marked the end of the Napoleonic age in the city: after the Congress of Vienna, the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia was formed. The Twenties opened up with the revolutionary movements of 1820-1821, which ended with a dramatic failure. In the years of the Italian Risorgimento, new hopes of independence spread leading to the 1848 Revolution – the so called Cinque Giornate (the five days of Milan) – and finally to Italy unification in 1861. The writer Alessandro Manzoni, nephew of Cesare Beccaria, witnessed and interpreted several times the hopes and expectations of the Milanese liberals, such as in his masterpiece The Betrothed.

03. Pompeo Calvi, The Arch of the Peace under construction, oil on canvas, 1837, Milan, Civiche Raccolte Storiche, Palazzo Morando | Costume Moda Immagine, inv. 441

But, despite the political tension, in the first half of the 19th century, Milan was filled with intense economic activities, which contributed to the modernization of its productive structures (from agriculture to textile) and preparing the city to be the driving force of the new-born Nation.

From this short introduction we can well understand how lively the city Thorvaldsen visited several times was.

We know for sure that Thorvaldsen had been interested in art and in paintings throughout his life and that, during a week-long stay in Milan along with the painter Johan Ludwig Lund, in the summer of 1819, they visited the Galleria, so the Pinacoteca di Brera, which is the Milanese Picture Gallery, and the city of Saronno. As we can read in their travel accounts (and I thank Laila Skjøthaug for sharing this piece of information) in 1819 they stayed at the Reichmann Hotel, where travelers coming from the North – especially Brits and Germans – would lodge during their stays in Milan.

04. Louis Cherbuin, View of Milan, Corso di Porta Romana, engraving, 1840-1850 ca., Milan, Civica Raccolta delle Stampe Achille Bertarelli, Castello Sforzesco, Albo D, tav. 78

The very famous Reichmann Hotel overlooked corso di Porta Romana, even today one of the main streets of the city, not far away from the Cathedral and the very centre of the city, piazza del Duomo. The Cathedral was founded at the end of the 14th century at the behest of the duke of Milan Gian Galeazzo Visconti and entirely built in Candoglia marble, a type of marble with white-pink and gray shades which was for the exclusive use of the Duomo.

The Cathedral took nearly six centuries to complete: the facade was completed in the Napoleonic era; statues and spiers have been added throughout the 19th century and the bronze doors were only mounted after Second World War. Not to mention the continuous restorations and replacements of the most ruined statues, which are now housed in the Cathedral Museum. All this continuous work has led to the birth of a famous Milanese saying to indicate a complicated and time-consuming job or simply an annoyingly long story: in fact we say longh cumè la fabrica del domm, which means “as long as the Duomo factory”.

05. Luigi Bisi, View of the Milan Cathedral, watercolour, 1830-1850 ca, Milan, Civiche Raccolte Storiche, Palazzo Morando | Costume Moda Immagine, inv. F.B. Cart. P. 1.7

Anyway, the Duomo was for sure in Thorvaldsen’s time one of the strong points of the city, as we can understand by reading the testimony of the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley from 1818:

«This cathedral is a most astonishing work of art. It is built of white marble, and cut into pinnacles of immense height, and the utmost delicacy of workmanship, and loaded with sculpture. The effect of it, piercing the solid blue with those groups of dazzling spires, relieved by the serene depth of this Italian heaven, or by moonlight when the stars seem gathered among those clustered shapes, is beyond any thing I had imagined architecture capable of producing. The interior, though very sublime, is of a more carthly character, and with its stained glass and massy granite columns overloaded with antique figures, and the silver lamps, that burn forever under the canopy of black cloth beside the brazen altar and the marble fretwork of the dome, give it the aspect of some gorgeous sepulchre. There is a solitary spot among those aisles, behind the altar, where the light of day is dim and yellow under the storied window, which I have chosen to visit, and read Dante there».

06. Luigi Bisi, View of the Milan Cathedral (The “gugliotto”), watercolour, 1830-1850 ca, Milan, Civiche Raccolte Storiche, Palazzo Morando | Costume Moda Immagine, inv. F.B. Cart. P. 1.4

In 1819, Thorvaldsen visited the Brera Picture Gallery and other non-specified churches in town and in Saronno.

Saronno is a town on the road that leads from Milan to Varese and was the destination of a real pilgrimage throughout the 19th century: Antonio Canova visited the city as well in 1810. Travelers – be they artists or scholars – went to the Sanctuary of the Beata Vergine dei Miracoli to admire above all the frescoes by Gaudenzio Ferrari and, even more, by Bernardino Luini, the latter being probably the most loved Lombard artist in the 19th century.

07. Carlo Rampoldi, Christ among the Doctors (by Bernardino Luini), etching, 1814, Milan, Civica Raccolta delle Stampe Achille Bertarelli, Castello Sforzesco, inv. Art. g. 11-35

In Saronno, around 1525, Luini painted one of his masterpieces, Stories of the Virgin: the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, as well as the Adoration of the Kings along with the Fathers of the Church, the Sibyls, the Prophets and so on. One of the most loved and known panels in Saronno was the one with Christ among the Doctors. The painting owes its fame to the presence, on the far right, of a gray-haired and bearded old man who, starting from the 17th century and for a long time, was believed to be a self-portrait of the painter.

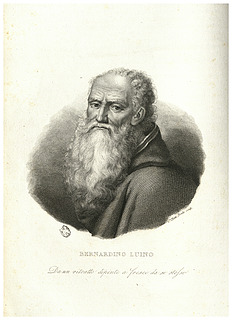

08. Caterina Piotti Pirola, Portrait of Bernardino Luini (from the fresco in Saronno), from Iconografia italiana degli uomini e delle donne celebri all’epoca del risorgimento delle scienze e delle arti fino ai nostri giorni, 1837, Milan, Civica Raccolta delle Stampe Achille Bertarelli, Castello Sforzesco, Vol. R 169, tav. 13

Bernardino Luini, known also as the Lombard Raphael, was a painter originally from Lake Maggiore who managed to combine references to Leonardo and Raphael while creating a personal, sweet and recognizable style, much loved particularly in the 19th century, as already said. Thanks also to an industrious workshop, he was able to work a lot throughout Lombardy and Milan, both for private collectors and churches.

In Milan, one of his masterpieces is the decoration of the church of San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, a most evocative place in the city. San Maurizio is a church formerly part of a Benedictine cloister which is still today entirely covered with frescoes, especially by Luini, his workshop and his sons. The fame of this place in the 19th century is boundless: it is mentioned by Stendhal, Balzac, Proust, Henry James and great artists went there to study Luini’s frescoes. Just to make a few examples, in 1806 Jean-August-Dominique Ingres visited the monastery, as we can see from some sketches now in the Ingres-Bourdelle Museum in Montauban. In 1858, the French painter Gustave Moreau was there too and he copied in pencil the Saints Lucy and Apollonia, but a detail of the Martyrdom of Saint Maurice was there too and, in the very same years, the Milanese photographer Luigi Sacchi took pictures of the frescoes. In the summer of 1862, it was instead the turn of the English John Ruskin and the pre-Raphaelite Edward Burne-Jones, and the list could go on and on…

09-10. Luigi Sacchi, Frescoes of the Besozzi Chapel in San Maurizio (by Bernardino Luini), 1857-1859 ca., Milan, Civico Archivio Fotografico, © Comune di Milano – Tutti i diritti riservati, invv. RLB 2609, RLB 2621

The huge fame of San Maurizio allows to suppose Thorvaldsen visited the church too, as we can imagine him taking a tour to another city masterpiece: Santa Maria delle Grazie with Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper in the refectory of the former Domenican monastery. Santa Maria delle Grazie is just a few steps away from San Maurizio and was (and still is) one of the main destinations for travellers in Milan: Goethe for example visited the refectory in 1788 and witnessed first-hand the very deteriorated painting. Nevertheless, Goethe wrote extremely beautiful pages about the Last Supper, stressing for example how «The harmonious interplay between physiognomy and gesture is masterfully rendered, as are the positioning and the contrasting movements of the arms and the hands».

Leonardo painted the Last Supper for the duke Ludovico Maria Sforza aka Ludovico il Moro between 1495 and 1498 with an experimental technique – a tempera mixed with oil spread on two layers of dry plaster – which, on one hand, compromised the good conservation of the painting, but, on the other hand, allowed the artist to create a mural very rich in colour and to paint something very precious with regards to details. But what strikes the most, and is the real innovation of the Last Supper, is the representation of the so called “movements of the soul” of the Apostles, as Goethe already highlighted. The faces and gestures of Christ’s followers, studied from life, are frozen in the dramatic moment of the announcement of the betrayal: Andrew raises his hands and shows his palms, as if to excuse himself; Peter reaches out to John, the youngest of the group, moving to Judas who, unlike the more traditional representations, is not isolated and is already holding the bag with the money he would receive for having betrayed Jesus. The more composed gestures of Judas Thaddeus, Simon and Matthew are counterbalanced by the amazement of Giacomo Maggiore, who opens his arms; Thomas points to the sky with one finger, while Philip touches his chest.

Today we are very lucky, because in the past centuries, and in Thorvaldsen’s time as well, the Last Supper was much more ruined due to the deterioration of the painting. Its disappearance was given for imminent: the mural was defined as the “eternal sick person”, the “dying person”, the “corpse” and the “ghost”, because very little or nothing was to be seen. For this reason, the scholar and painter Giuseppe Bossi had been asked for a copy. From this cartoon, a mosaic copy was made to preserve the memory of this masterpiece for the centuries to come. This mosaic copy, made in 1810-1817 by Giacomo Raffaeli, is for different reasons today kept in the Minoritenkirche in Vienna.

11. Raffaello Morghen, The Last Supper (by Leonardo da Vinci), etching, 1797 ca – 1800, Milan, Civica Raccolta delle Stampe Achille Bertarelli, Castello Sforzesco, Art. f. s. 8-17

In Thorvaldsen’s time, travellers, collectors and connaisseurs hunted for works by Leonardo who spent almost twenty years of his life in Milan. At the Ambrosiana Library, beautiful drawings are kept including the Codex Atlanticus which is the largest collection of drawings and writings by Leonardo, brought back to Milan after the Congress of Vienna, in 1815, after being requisitioned by Napoleon and brought to Paris.

At the Ambrosiana Picture Gallery was also kept (and still is) the Portrait of a Musician, one of the most intense portraits of the master, the only painting on panel by Leonardo to have remained in Milan. In the 19th century, the masterpiece was often believed to be a portrait of the duke Ludovico il Moro; only at the beginning of the 20th century, thanks to a restoration, the score was discovered and so they today believe it portrays a musician.

These works of art are kept in the Biblioteca e Pinacoteca Ambrosiana (Ambrosiana comes from Ambrosius, the bishop and then saint, patron of the city of Milan, so saying “Ambrosiana or Ambrosiano” has the same meaning as saying Milanese). It is a very ancient institution founded by cardinal Federico Borromeo at the beginning of the 17th century: the Library was one of the earliest libraries to grant access to all who could read and write and it was conceived by its founder as a centre for study and culture. A few years after the foundation of the Library, Federico Borromeo donated his collection of paintings, drawings and statues to give birth to the Ambrosiana Picture Gallery. The cardinal’s collection was striking, and comprised for example the School of Athens by Raphael, the largest renaissance cartoon that has survived to this day, made as a preparatory work for the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican.

The Ambrosiana Library also kept curiosities which were very much loved in the 19th century, as the lock of hair of Lucrezia Borgia, the daughter of Pope Alexander VI. These blonde and delicate hair were kept together with nine letters written by Lucrezia to Pietro Bembo, the famous humanist cardinal and man of letters. This lock of blonde hair almost became a cult object during the centuries: in 1816 Lord Byron visited the library and wrote he read «the prettiest love letters in the world», committing some to memory because he was not allowed to make copies; in addition to that, according to a tradition, Byron took advantage from a librarian’s distraction, to steal one of the long strands from Lucrezia’s lock of hair, describing them as «the prettiest and fairest imaginable».

For a long time, the Ambrosiana Library and Art Gallery was the only public museum in Milan, even at the beginning of the 19th century when the Brera Art Gallery was still under construction. While we have to wait the second half of the 19th century for the Civic Museums to be founded. Connaisseurs, travellers and artists, such as Thorvaldsen, however, could visit a lot of private collections, often owned by the noble and most important families of the city who combined masterpieces collected over the centuries with new works, often coming from suppressed churches and monasteries already at the end of the 18th century, under Austrian rule, but even more in the Napoleonic years.

The choices of the Milanese collectors were guided by scholars and experts of local glories who helped rediscover ancient Lombard art, in particular the painters active before the arrival of Leonardo da Vinci in Milan (1482), at his times and his followers. A lot of these works were summoned in private collection or exhibited in museums – such as the Pinacoteca di Brera, they were forming – but these Lombard paintings were also sought after by and sold to foreign connaisseurs and collectors, spreading the knowledge and love for these works of art throughout Europe and beyond.

This happened, for example, talking of a masterpiece, to Leonardo’s second version the Virgin of the Rocks. This painting was part of a grand altarpiece kept in the church of San Francesco Grande, a Franciscan convent in Milan which was suppressed at the end of the 17th century and no longer exists. Bought by the English painter Gavin Hamilton, the panel was brought to England and, after several transitions, was sold in 1880 to the National Gallery of London, where it is still kept.

As we said, even the major Milanese collectors could not miss works by the Lombard Renaissance masters, but the focus was above all on Leonardo and his school or Bernardino Luini. Just to give an example, until the mid-sixties of the 19th century, the so-called Litta Madonna – from the surname of the collector – was still in Milan; today, in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. This Madonna is a very refined painting, which entered the Litta collection in 1813, depicting the Virgin nursing the Child. While some scholars considered the painting to be an original by Leonardo, other scholars favor the names of Marco d’Oggiono or, more likely, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, two of the best pupils of Leonardo in Milan, who painted the panel starting from an idea and a drawing by Leonardo himself.

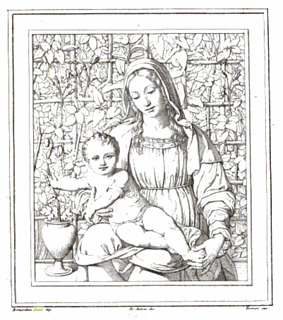

As a conclusion of this brief journey in the 19th century Milan, we enter the Brera Picture Gallery and take a look at Luini again: we already said Luini was one probably the most loved Lombard artist in the 19th century. Bernardino Luini’s Madonna of the rose garden has belonged to the Brera collections since 1824: this is one of the painter’s masterpieces, showing the Leonardesque influence in the nuanced technique, the so called sfumato. It was bought from a dealer of paintings and admired in the Brera by almost all the connaisseurs and painters passing through Milan.

12. Cesare Ferreri, Antonio De Antoni, Madonna of the rose garden (by Bernardino Luini), from R. Gironi, Pinacoteca del Palazzo Reale delle scienze e delle arti di Milano, III, Milan, Imp. Regia Stamperia, 1833

13. Bernardino Luini, Madonna of the rose garden, oil on canvas, 1500-1510, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

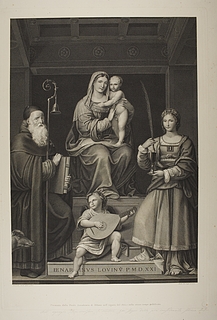

As Laila Skjøthaug pointed out, from a letter dated August 15th 1833 by the engraver Michele Bisi, we know that Thorvaldsen saw and admired the Virgin with Child and Saints Anthony the Abbot and Barbara during one of his visits to the Brera Picture Gallery. This Madonna, painted by Luini in 1521 for one of the altars of the demolished church of Santa Maria di Brera, has been kept in the Milanese Museo della Scienza e della Tecnologia since 1952 as a long-term loan from Brera.

Michele Bisi was one of the best engravers working in Milan; he owed his fame to his engravings after very famous artworks and, in particular, to his contribution in the monumental Pinacoteca del Palazzo Reale delle Scienze e della Arti di Milano dedicated to the illustration of the masterpieces of the Brera Picture Gallery, edited in Milan from 1812 to 1833 with the commentary by Robustiano Gironi. That’s whay, together with the letter, Bisi sent Thorvaldsen two of his most beautiful and famous engravings, for which he was awarded by the Brera Academy. The first one after the Madonna by Luini (awarded in 1815), the second one after a lost painting showing Venus embracing Cupid which Andrea Appiani made for Giovanni Battista Sommariva between 1806 and 1808 (the engraving was awarded in 1822). The two prints are now in the collections of the Thorvaldsen’s Museum.

14. Michele Bisi, Virgin with Child and Saints Anthony the Abbot and Barbara (by Bernardino Luini), copper engraving, 1815, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum, Collection of Prints, inv. E379

15. Michele Bisi, Venus and Cupid (by Andrea Appiani), copper engraving, 1819, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum, Collection of Prints, inv. E380

Referencer

Short bibliography for both articles

Aurora Scotti: Brera 1776-1815: nascita e sviluppo di una istituzione museale milanese, Firenze 1979.

Annalisa Zanni: “Collezionismo e mercato artistico a Milano: smembramenti, vendite, restauri”, in: Mauro Natale, Alessandra Mottola Molfino (eds.): Zenale e Leonardo. Tradizione e rinnovamento della pittura lombarda, Milano 1982, pp. 243-250.

Maria Cristina Gozzoli, “Maria Stuarda nel momento che sale il patibolo”, in: Maria Cristina Gozzoli, Fernando Mazzocca (eds.): Hayez, Milano 1983, pp. 131-136.

Dyveke Helsted: “Thorvaldsen collezionista di arte moderna”, in: Elena di Majo, Bjarne Jørnaes, Stefano Susinno (eds.): Bertel Thorvaldsen 1770-1844. Uno scultore danese a Roma, Roma 1989, pp. 241-244.

Fernando Mazzocca: “Thorvaldsen e i committenti lombardi”, in: Elena di Majo, Bjarne Jørnaes, Stefano Susinno (eds.): Bertel Thorvaldsen 1770-1844. Uno scultore danese a Roma, Roma 1989, pp. 113-129.

Bjarne Jørnaes: “Thorvaldsen com’era”, in: Elena di Majo, Bjarne Jørnaes, Stefano Susinno (eds.): Bertel Thorvaldsen 1770-1844. Uno scultore danese a Roma, Roma 1989, pp. 25-34.

Fernando Mazzocca: Francesco Hayez. Catalogo ragionato, Milano 1994, pp. 173-174.

Daniele Pescarmona: “I monumenti commemorativi”, in: Giacomo Agosti, Matteo Ceriana (eds.): Le raccolte storiche dell’Accademia di Brera, Firenze 1997, pp. 159-169.

Giuliana Ricci: “Il luogo della cultura, dell’arte e della scienza: Brera”, in: Fernando Mazzocca, Alessandro Morandotti (eds.): La Milano del Giovin Signore. Le arti nel Settecento di Parini, Milano 1999, pp. 172-181.

Johann Wolfgang Goethe: Il Cenacolo di Leonardo, traduzione di Claudio Groff, con uno scritto di Marco Carminati, Milano 2004.

Fernando Mazzocca: “Canova e Milano”, in: Antonio Canova. La cultura figurativa e letteraria dei grandi centri italiani, Bassano del Grappa 2006, pp. 7-13.

Chiara Nenci: “Colla opinione e coll’esempio: Giuseppe Bossi e Canova”, in: Antonio Canova. La cultura figurativa e letteraria dei grandi centri italiani, Bassano del Grappa 2006, pp. 15-21.

Francesca Valli: “Con nostro vantaggio e con vostro onore. Canova e l’Accademia di Brera”, in: Antonio Canova. La cultura figurativa e letteraria dei grandi centri italiani, Bassano del Grappa 2006, pp. 23-30.

Eleonora Carantini (ed.): Milano è una seconda Parigi. Viaggiatori britannici e americani a Milano, Palermo 2007.

Alessandro Morandotti: Il collezionismo in Lombardia. Studi e ricerche tra ’600 e ’800, Milano 2008.

Chiara Battezzati (ed.): Carl Friedrich von Rumohr e l’arte nell’Italia settentrionale, in «Concorso. Arti e lettere», III, 2009, pp. 6-23.

Matteo Ceriana (ed.): Il ritorno di Napoleone. Il gesso di Canova a Brera restaurato, Milano 2009.

Matteo Ceriana, Emanuela Daffra (eds.): Raffaello. Lo Sposalizio della Vergine restaurato, Milano 2009.

Isabella Marelli (ed.): La Sala dei Paesaggi. 1817-1822, Milano 2009.

Luisa Arrigoni: “La fondazione, le collezioni, gli allestimenti”, in Luisa Arrigoni, Valentina Maderna (eds.): Pinacoteca di Brera. Dipinti, Milano 2010, pp. 23-37.

Sandrina Bandera: “La vitalità di una istituzione”, in: Luisa Arrigoni, Valentina Maderna (eds.): Pinacoteca di Brera. Dipinti, Milano 2010, pp. 9-21.

Stefano Grandesso, Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), Milano 2010.

Sandra Sicoli (ed.): Milano 1809. La Pinacoteca di Brera e i musei napoleonici, Milano 2010.

Chiara Battezzati: “Milano. San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore”, in: Giovanni Agosti, Rossana Sacchi, Jacopo Stoppa (eds.): Bernardino Luini e i suoi figli. Itinerari, Milano 2014, pp. 122-147, n. 16.

Chiara Battezzati: “Madonna con il Bambino (Madonna del roseto)”, in: Giovanni Agosti, Jacopo Stoppa (eds.): Bernardino Luini e i suoi figli, Milano, 2014, pp. 168-171, n. 27.

Tommaso Tovaglieri: “Saronno. Santuario della Beata Vergine dei Miracolo”, in: Giovanni Agosti, Rossana Sacchi, Jacopo Stoppa (eds.): Bernardino Luini e i suoi figli. Itinerari, Milano 2014, pp. 185-206, n. 25.

Francesco Leone, Andrea Appiani pittore di Napoleone, Milano 2015.

Omar Cucciniello: “Giuseppe Bossi e la copia dell’Ultima Cena di Leonardo”, in: Fernando Mazzocca, Francesca Tasso, Omar Cucciniello (eds.): Bossi e Goethe. Affinità elettive nel segno di Leonardo, Milano 2016, pp. 107-131.

Emanuela Daffra, Cristina Quattrini, Giovanni Agosti (eds.): Primo Dialogo. Raffaello e Perugino, Milano 2016.

Elena Catra: “Il glorioso e polemico ritorno delle opere d’arte requisite da Napoleone: i Cavalli di San Marco e il Giove Egioco”, in: Fernando Mazzocca, Paola Marini, Roberto de Feo (eds.): Canova, Hayez, Cicognara. L’ultima gloria di Venezia, Venezia 2017, pp. 156-170.

Fernando Mazzocca: “Hayez vero erede di Canova crea il Romanticismo e abbandona Venezia per Milano”, in: Fernando Mazzocca, Paola Marini, Roberto de Feo (eds.): Canova, Hayez, Cicognara. L’ultima gloria di Venezia, Venezia 2017, pp. 278-281.

Omar Cucciniello: “Il monumento a Giuseppe Longhi nel Palazzo di Brera: un confronto tra Pompeo Marchesi e Thorvaldsen”, in: Stefano Grandesso, Francesco Leone (eds.): Dall’ideale classico al Novecento. Scritti per Fernando Mazzocca, Milano 2018, pp. 79-85.

Giuseppina Di Gangi: “Le sale napoleoniche e la galleria dei veneti”, in: Emanuela Daffra, Marco Tanzi (eds.): Sesto Dialogo. Attorno agli Amori. Camillo Boccaccino sacro e profano, Milano 2018, pp. 82-93.

Francesco Leone: “Sopravvivenze classiche. La resistenza contro il Romanticismo”, in: Fernando Mazzocca (ed.): Romanticismo, Milano 2018, pp. 41-43.

Andrea Di Lorenzo: “Vicende collezionistiche e fortuna critica della Madonna Litta fra XV e XIX, prima della partenza per la Russia”, in: Andrea Di Lorenzo, Pietro C. Marani (eds.), Leonardo e la Madonna Litta, Milano 2019, pp. 49-57.

Fernando Mazzocca: “Canova e Thorvaldsen a Milano e in Lombardia”, in: Stefano Grandesso, Fernando Mazzocca (eds.): Canova Thorvaldsen. La nascita della scultura moderna, Milano 2019, pp. 53-59.

Claudio Salsi: “Raffaello, persistenza del mito: dalle botteghe dei Maiolicari al Neoclassicismo”, in: Claudio Salsi (ed.): Giuseppe Bossi e Raffaello al Castello Sforzesco di Milano, Milano 2020, pp. 17-31.

Omtalte værker

Sidst opdateret 02.06.2023