Why Are There Portrait Busts at Thorvaldsens Museum?

- Ernst Jonas Bencard, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2020

- Translation by Dorte Herholdt Silver

This is a re-publication of the article ‘Why Are There Portrait Busts at Thorvaldsens Museum?’, in: Jane Fejfer & Kristine Bøggild Johannsen (eds.): Face to Face. Thorvaldsen and Portraiture, Thorvaldsens Museum 2020, p. 174-179.

- 1. Silly question

- 2. The low status of busts

- 3. The installation of busts

- 4. Equality

- 5. Freedom

- 6. The busts as a key

- 7. References

Fig. 1. The busts look at art – as a substitue for the viewer

Thorvaldsens Museum, Room 18, ground floor

Silly question

Some readers may find the question in the title of this article silly or banal. Naturally, the museum’s collection of portrait busts exists because the busts were created by Bertel Thorvaldsen. And of course, they should be on display in the sculptor’s museum – where else? They are a part of his oeuvre and of the gift he left us all in his last will and testament, so it might seem strange to question why the busts are at Thorvaldsens Museum. These reasonable objections notwithstanding, I nevertheless invite the reader to dwell on this silly question. The point is, we often take portrait busts for granted and thus forget to look at them, forget why and how they are present. They are overlooked – not only by visitors to Thorvaldsens Museum but also in art history.

The low status of busts

So far, only two scholars have dealt with Thorvaldsen’s portrait busts in any depth, but neither had any doubt that the busts are largely seen as cuckoos in the nest of his life’s work: in 1963–1965, the Danish art historian Else Kai Sass published a comprehensive monograph dedicated exclusively to the sculptor’s portrait busts; to this day, her publication remains the standard work on this part of Thorvaldsen’s production. In three weighty tomes, she sought to elevate the status of the portrait busts. However, she was well aware that the busts were up against a strong tradition that considered them inferior works. She writes in the introduction to her treatise, [...]

‘Thorvaldsen himself did not consider the portrait busts to be a significant part of his production. Time and again, he complained that they took too much time away from what he considered his true calling, to create statues and reliefs. [...] Posterity also took more notice of Thorvaldsen’s statues and reliefs, and during early years, the board of Thorvaldsens Museum repeatedly declined to acquire marble busts that were offered to the museum’.

As early as 1926, the Danish writer Johannes V. Jensen had laid the basis for a rehabilitation of the portrait busts with his book on the topic. However, he too was well aware that the busts were overshadowed by Thorvaldsen’s other sculptures – the statues and reliefs. Jensen pointed out [...]

‘[...] how little attention Thorvaldsen’s contemporaries, his biographers and chroniclers, paid to the busts compared to the, in our assessment, excessive enthusiasm occasioned by the figures [i.e., the statues]. Thorvaldsen’s biographer, the Danish writer Thiele, finds that the busts are so numerous that there is no point in even addressing them! [...] Posterity tended to regard a sculptor’s portrait busts as a casual craft pursuit’.

Despite Sass’s and Jensen’s attempts to promote Thorvaldsen’s busts, their poor reputation still clings to them. They are considered less significant than Thorvaldsen’s statues and reliefs and so continue to fly under the art historian’s radar – a sad state of affairs that the present exhibition will hopefully rectify.

The installation of busts

The marginalized position of the busts does not stem from art historians questioning their artistic merit over the years. Far from it. Instead, the root cause is probably general prejudice towards portraits in general, which have caused Thorvaldsen’s busts to be neglected in the reception of his work. An in-depth discussion of this issue lies outside the scope of the present context. Instead we will reflect on the simple fact that the busts are in fact on display at Thorvaldsens Museum and are not in any way stood in the corner. On the contrary, the busts are present on an equal footing with Thorvaldsen’s other works of art.

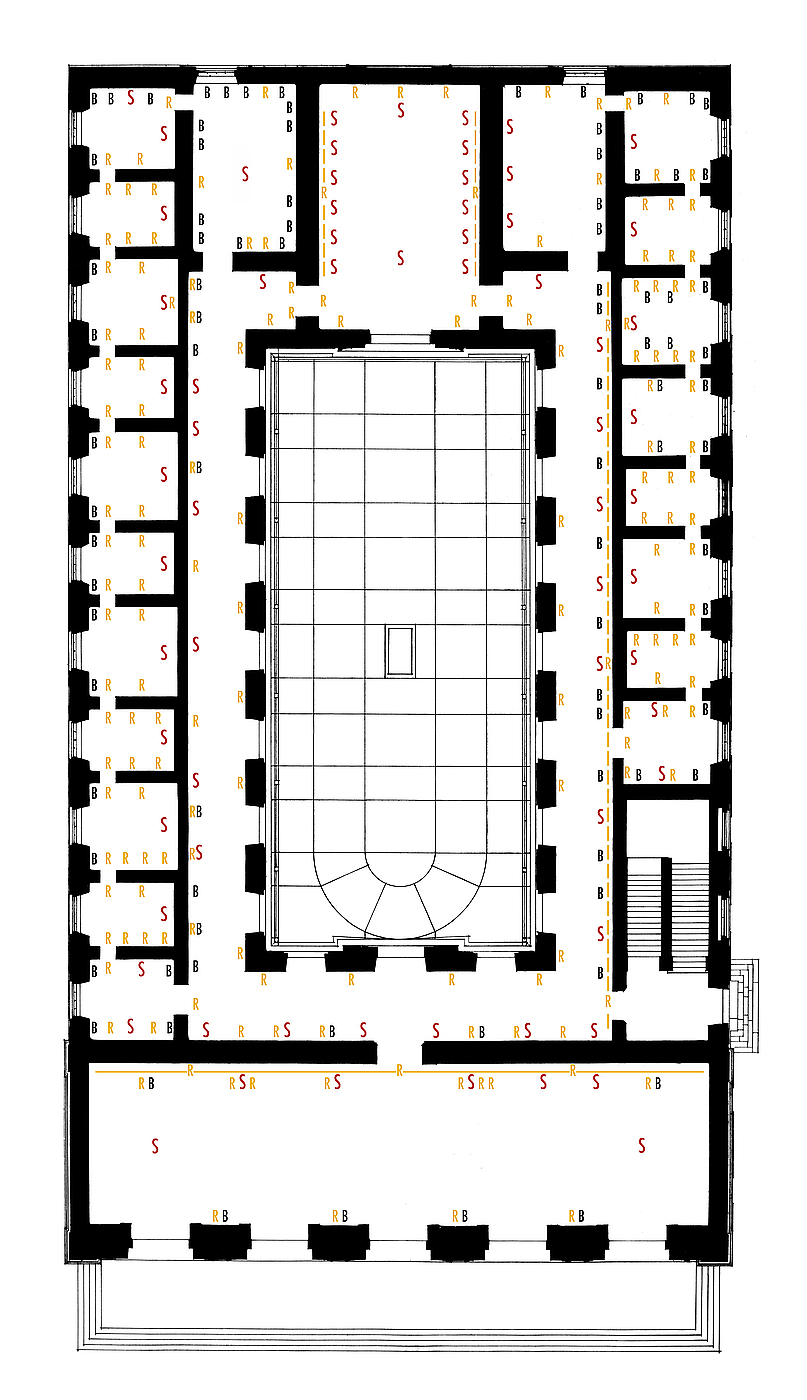

Fig. 2. Plan of Thorvaldsens Museum, ground floor.

The location of each of Thorvaldsen’s works is indicated:

Black B for portrait bust, red S for statue and yellow R for relief.

If one considers the plan of the placement of the sculptor’s works on the ground level of the building, the museum’s main floor (see fig. 2), it is striking that the busts are evenly distributed throughout the rooms and that busts, statues and reliefs vary in a calm and regular rhythm. Visitors encounter the three categories of works with equal frequency throughout the building, also on the two other floors. Although, due to their size, the statues naturally attract more attention, the installation of Thorvaldsen’s works at the museum in no way favours one category over any other. Thus, a basic look at the plan for the displays tells us that busts, statues and reliefs are clearly intended to interact closely. Hence, the purpose here is to attempt to answer what we can read from the fact that Thorvaldsen’s three work categories are indeed treated equally. How should we understand the symbiosis of work types that the visitor encounters in the museum? Why did Thorvaldsen choose to exhibit his statues and reliefs alongside his portrait busts? Why did he choose to mix his mythological, historical and allegorical works with the contemporary ‘naturalism’ of his portraits? An answer to these questions would enable a better understanding of how we can appreciate Thorvaldsen’s portrait busts and what role they played in his total production.

In all fairness, we do not have Thorvaldsen’s word that the presentation of his works reflects his own assessment of his portraits and the other categories of works. However, we do know that he and the museum’s Danish architect, Gottlieb Bindesbøll, discussed the interior design of the museum and the presentation of the sculptor’s works in depth. Although the content of these discussions is not documented, it is still the intent here to interpret the presentation of Thorvaldsen’s portrait busts as a conceptual manifestation or a ‘work of art’ in its own right. The interior of Thorvaldsens Museum has remained largely unchanged since the museum opened as a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art, and the totality of the installation is not arbitrary but offers key insights into Thorvaldsen’s ideas about his works.

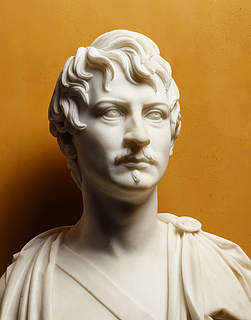

Equality

In the museum’s presentation of the portraits, we note another basic, yet all the more significant, feature: the 140 busts on display are all presented in an almost similar manner. The portraits are placed on pedestals in two basic forms: round columns or square pillars. Busts mounted on a round base are placed on a column, while busts shaped like a herm – that is, with a square outline – are placed on a pillar that is flush with the outline of the herm. The height of columns and pillars adheres fairly consistently to a standard of about 145 centimetres, and all the pedestals are painted in the same colour. This consistent presentation lends a degree of uniformity and anonymity to the portrayed persons.

A similar tendency is seen in the rather arbitrary grouping of the portrayed individuals. The busts are not arranged according to a plan that considers the depicted individuals’ biographical context; generally, we bounce around Thorvaldsen’s clientele in its arbitrary make-up. The most famous European statesman at the time, Prince Metternich, for example, is placed side by side with the little-known English businessman Edward Divett. Only rarely do we see any logic in the placement of individual busts: the portraits of the Danish royal family, for example, are all placed in the same room; the busts of the English banker and interior designer Thomas Hope and his family are placed near Jason, which was commissioned by Hope in 1803; and the busts of the Norwegian art collector Jørgen Knudtzon and his life partner, the wealthy Scot Alexander Baillie, are placed as close together as decency at the time permitted. In general, however, the biographies of those portrayed are not a decisive parameter in the presentation. Instead, the distribution of the busts was a matter of symmetry: if a bust on a column, for example, is placed in a corner in one of the small side chapels – the so-called berths – the opposite corner in the same berth will also feature a bust on a column. If a herm on a pillar is placed on one side of a statue, the statue will also be flanked by a herm portrait on a pillar on the other side. This formal principle is observed consistently and in great detail and clearly governed the placement of the portrait busts, see fig. 2.

Thus, the installation of the busts is characterized by an even distribution; serial, depersonalized pedestals; and non-biographical symmetry. At first glance, these principles might be seen to suggest that the busts were lesser works, regarded merely as fillers that were fitted in wherever there was room among the reliefs and statues, with no real content-based interaction between the pieces.

Such an interpretation, however, would only repeat the bust discrimination of the past. If we instead take a positive view of the uniform presentation of the busts, as opposed to them being treated as specific individuals, they appear more as generic portraits. In that light, we may see the presentation of the busts differently: now, the flock of heads at Thorvaldsens Museum gives rise to a social space characterized by a principle of equality among those depicted. Everyone – from the King of Bavaria to Mrs Høyer – is presented in the same fashion. They are all equally tall and appear equally worthy. In a broader sense, the uniformity of the busts may be regarded as a reflection of the ideals of equality that sprang from the 18th-century philosophy of Enlightenment and the French Revolution, particularly since these revolutionary ideas run as a central theme throughout Thorvaldsen’s oeuvre and life-long practice.

Ludwig 1. of Bavaria, A232 |

Sophie Dorothea Høyer, A763 |

Now, the reader might object to the fact that most of those portrayed belonged to the upper echelons of society – about 60% of Thorvaldsen’s busts depict royalty or nobility – which of course reflects the fact that only the wealthiest could afford to commission a portrait from the sculptor. He was no social realist. Thus, calling Thorvaldsens Museum a People’s House would be stretching the point; however, the gradual depersonalization of the busts in favour of a more egalitarian presentation still points in that direction. The Danish painter Jørgen Sonne’s frieze on the museum’s facades supports this point. The frieze is renowned, in part, as one of the first monumental representations in the public realm of all the estates of society, except – notable in their absence – the monarchy and nobility.

The ideal of equality is also tangibly manifest in the way Thorvaldsen formed his busts. His reliefs and statues depict historical and mythological themes, where the figures are identifiable by virtue of their attributes: Cupid with the arrow, Apollo with the lyre and so forth. By contrast, the portrait busts are almost completely bereft of historical, mythological and allegorical trappings. They generally appear completely naked. They do not express themselves through exterior characteristics, only through a sort of natural dignity. The vast majority of the busts are not decorated with markers of social status or rank, pomp and circumstance but are present only by virtue of their appearance and character. Thorvaldsen’s busts eschew exterior status symbols, and the desire to establish this equality is particularly evident in some of the sculptor’s sepulchral monuments. For example, in a comment on the full-figure portrait of the Duke of Leuchtenberg, the museum’s first director, Ludvig Müller, wrote in 1848 that we see the Duke [...]

‘[...] about to depart life; ceremonial baton, helmet, armour, the symbols of his earthly power, are all laid down, and with his hand on his heart [...] he surrenders to the muse of history his last jewel, the wreath of honour’.

Eugène de Beauharnais, Duke of Leuchtenberg, A156

Like everyone else, in death, the Duke has to surrender his insignia. This theme of undressing appears in many other contemporary sepulchral monuments and is clearly expressed in a eulogy given by Thorvaldsen’s close friend, the Danish writer Knud Lyne Rahbek, in 1815:

‘In the light of the funeral lamp fade all the phantom lights that so often blind us mortals; in its flame, all the follies of lineage and rank evaporate, and all that remains is man’s inner worth’.

In death, we are all equal – and all men are created equal, to quote one of the 18th-century sources of the modern ideal of equality, the American Declaration of Independence, from 1776. Thorvaldsen’s busts manifest the democratic ideal in his museum. In their naked uniformity and particular arrangement, they represent a classless, egalitarian utopia – a conceptual work of art, in other words. ‘All people become brothers’ is a famous line in the German philosopher and poet Friedrich Schiller’s Ode to Joy. And just as Beethoven used Schiller’s ode as the lyrics for the fourth movement of his Ninth Symphony, Thorvaldsen and Bindesbøll may, in creating their architectural symphony, have similarly sought to use the portrait busts to convey a sculptural installation-based vision of the egalitarian ‘brotherhood’ that at the time was on the cusp of replacing the absolute monarchy.

Freedom

The advantage of regarding Thorvaldsen’s portraits as generic – as the busts themselves seem to suggest – is that we can ignore the distraction of considering who they portray. Seeing them in this light brings out another basic observation regarding their installation: What are they ‘doing’, all these heads? Well, they are looking at art, of course! All the busts are placed against a wall, and they all have a relief and/or a statue within their field of vision (see fig. 1 and 3). The arrangement thus gives the illusion that Thorvaldsen’s statues and reliefs, with their historical, mythological and allegorical staging, are regarded by his portraits, which are themselves characterized by the absence of these features. The reliefs and statues express themselves through a complex allegorical imagery, while the busts manage without. This contrast lets the busts play the role as our – the beholders’ – representatives. In the way they are arranged, they do exactly what the museum-goers do: they are inspecting the exhibits. ‘Naked’, they can be anyone, from any historical time.

Why did Thorvaldsen and Bindesbøll choose to include the viewing of art as a persistent theme in their joint Gesamtkunstwerk? Why did they make this meta-comment over and over again? Incidentally, the theme is not only present in the installation of the artworks but is also a prominent aspect in many of Thorvaldsen’s statues, which often portray a figure – for example Ganymede, Venus, Hebe, Mars, Cupid and Psyche – carefully inspecting something, as if it were a work of art, the same way we as beholders look at art: wondering, uncomprehending, composed. So why is this theme so important to Thorvaldsen?

A854 |

A853 |

A874 |

A6 |

A27 |

The answer is that looking at art can teach us to become free human beings. Nothing less. Throughout Thorvaldsen’s career, the representation of freedom was a key theme. This idea was probably inspired by Schiller’s treatise on art philosophy from 1795: Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen (On the Aesthetic Education of Man), where the author attempts to reason out the relationship between artistic, individual and political liberty. Disappointed that the ecstasy of liberty during the first years of the French Revolution turned so soon to bloodlust, Schiller turned his gaze inward. In order to create ‘the most perfect of all works of art […] a true political freedom’, the individual first had to be free. And this liberation was only possible with art as the mediator. As Schiller put it, in a famous slogan: ‘Art is a daughter of Freedom’ and ‘beauty [i.e., art] […] is the only way that freedom has of making itself manifest in appearance’. According to Schiller, in order to create the free society that had failed to materialize in France, it was necessary first to edify, refine or aesthetically enlighten humankind: ‘to solve that problem of politics in practice [man] will have to approach it through the problem of the aesthetic, because it is only through Beauty that man makes his way to Freedom’. Briefly put: no external political freedom unless we first attain inner personal freedom.

How to translate these ideas into a tangible museum installation? They are most clearly manifested in the museum’s so-called berths. Here, Schiller’s ideas appear to be transformed into educational practice. Each berth contains one statue. This presentation of sculptures, which was innovative for its time, forms a free space for art, and the berths and the art they contain appear as an architectural image of the autonomy that art conquered from around 1800. In the berths, statues and reliefs are liberated from the authoritative religious, moral and political institutions that art was subordinate to until around 1800. Here, Thorvaldsen’s works unfold freely as ‘individuals’ with a mind of their own. They are ‘their own masters’, as the Danish art historian Julius Lange observes.

Thus, the installation of the works sees Thorvaldsen’s – and Schiller’s – ‘daughters of Freedom’ express their message of freedom, initially to the portrait busts, which observe them and thus receive aesthetic enlightenment, as proxies and instructional figures for us, the beholders. This transmission of freedom may – ideally – be translated into social practice. In Schiller’s words, ‘beauty alone can confer upon [man] a social character. Taste [i.e., art] alone brings harmony into society, because it fosters harmony in the individual’. Although Schiller was not blind to the utopian-idealist character of this connection between art, liberty, individual and society, the installation of artworks at Thorvaldsens Museum appears to convey this logic over and over again.

What is thus suggested here is that On the Aesthetic Education of Man should be read as a sort of philosophical manual to the arrangement of artworks at Thorvaldsens Museum. Although there are no explicit sources to support this idea, it appears highly likely that Schiller’s concepts were debated in the German-oriented intellectual avant-garde scene that Thorvaldsen was a part of, both before and after his departure for Rome in 1796–1797. However, regardless whether the sculptor was familiar with the philosopher’s thinking, Schiller’s treatise was far from the only source of the notion of art’s free autonomy that might have inspired Thorvaldsen and Bindesbøll to create their edifying freedom-oriented installation.

Fig. 3. Busts and reliefs interacting.

Thorvaldsens Museum, west corridor, first floor

The busts as a key

In his book, Johannes V. Jensen suggests that all Thorvaldsen’s portrait busts should be placed together in one place at the museum – in the inner courtyard, which would then have to be covered with a roof – in order to take them out of the shadow cast by the statues and the reliefs. His proposal is motivated, in part, by the stylistic difference between the busts and the two other categories of works. Jensen finds that the busts’ sober ‘Nordic’ realism makes them ‘significantly modern’ in contrast to the ‘Latin’ classicism of the reliefs and statues. However, following Jensen’s proposal would mean being guilty of the same discrimination that the busts have been subject to, only inverted. The point of the works installation in Thorvaldsen and Bindesbøll’s Gesamtkunstwerk is precisely that the busts are in the museum in interaction with the other works. The busts are present as generic portraits, because this clearly models the ideal of equality and Schiller’s utopia of freedom. They serve as keys, or as door-openers and eye-openers, to the statues and reliefs so that we not only register them in a slightly unengaged manner, as the retrospective recycling of myths and imagery from antiquity, but instead see them as relevant contemporary art like the busts. Thus, the generic busts play a leading role in the presentation of the Gesamtkunstwerk. They act as museum educators, taking us by the hand and pointing to two key themes in Thorvaldsen’s art – freedom and equality – that mankind have not yet managed to render outdated.

References

- Originally published in: Jane Fejfer & Kristine Bøggild Johannsen (eds.): Face to Face. Thorvaldsen and Portraiture, Thorvaldsens Museum 2020, p. 174-179.

- Nils G. Bartholdy: ‘Sørgeloger og mindeskjolde indtil 1856’, in: Acta Masonica Scandinavica vol. 15, København, Uppsala, Oslo & Reykjavik 2012.

- Ernst Jonas Bencard: Three Dogmas About Portrait Busts, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/en, 2019.

- Johannes V. Jensen & Aage Marcus: Thorvaldsens Portrætbuster, Copenhagen 1926.

- Julius Lange: Sergel og Thorvaldsen, Studier i den nordiske Klassicismes Fremstilling af Mennesket, Copenhagen 1886.

- Ludvig Müller: Thorvaldsens Museum. Første Afdeling. Thorvaldsens Værker, Copenhagen 1848.

- Else Kai Sass: Thorvaldsens Portrætbuster, Copenhagen 1963-65, vol. I-III.

- Friedrich Schiller: On the Aesthetic Education of Man in a Series of Letters, edited and translated by Elizabeth M. Wilkinson and L.A. Willoughby, Oxford & New York 1982 (reprinted 2005).

Last updated 11.10.2025