The Vases on the Thorvaldsen Museum

- Torben Melander, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 1982

- Translation by John Kendal

This is a re-publication of the article: Torben Melander: ‘The Vases on the Thorvaldsens’ Museum’, in: Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum (Communications from the Thorvaldsens Museum), 1982, p. 67-106.

For a presentation of the article in its original appearance in Danish, please see this facsimile scan. For a presentation of the article in its original appearance in English, please see this facsimile scan.

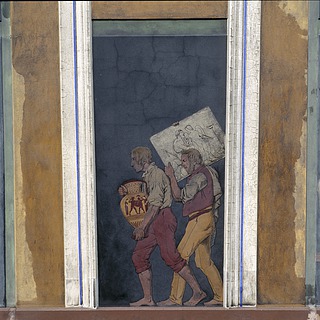

Fig. 1. Two men in boat. Section of east frieze, The Thorvaldsen Museum. Height of frieze: 218 cm. Executed by J. Sonne, 1850.

Vases on the Exterior Wall Frieze of the Museum

Sonne’s frieze (1846-1850) on the exterior walls of the Museum exhibits an idealized depiction of Thorvaldsen’s return to Copenhagen from Rome in 1838. On the east and south sides, where craftsmen and labourers are seen carrying Thorvaldsen’s works and pieces from his collections from the harbour and into the Museum, the representation is no less idealized. The triumphal procession is, naturally enough, dominated by a representative selection of Thorvaldsen’s sculptures. In addition there are packages and crates, with unknown contents, either in the process of being unloaded or already stacked up on the quayside awaiting further transport. In two cases, instead of Thorvaldsen’s sculptures two Greek vases are quite openly shown in transport. The first instance (fig. 1) is in the rowing boat on the east side of the frieze, where one of the two seated men is almost tenderly embracing a vase. Further on in the narrative of the frieze, in one of the narrow panels on the south side, we see two men, one of whom is carrying the relief of Cupid with Anacreon, while the second is bearing yet another Greek vase (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Two men carrying objects to the Museum. Section of the south frieze, the Thorvaldsen Museum. Height: 255 cm. Executed by J. Sonne, 1846-47.

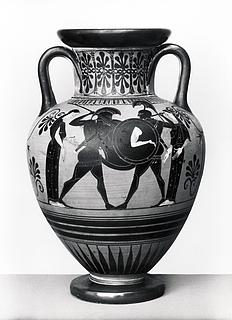

As might have been expected, both vases are to be found in Thorvaldsen’s antique collection (figs. 2 and 4). Certain inaccuracies in their representation are immediately apparent. The vase that is being rowed ashore has suffered most. From being a water jar, a hydria — with the three characteristic handles, it has been transformed into an amphora.

Fig. 4. Attic black-figure amphora. Height: 39,5 cm. C. 510 B.C. H552.

The most important change in the vase on the south frieze is that the handles are now attached to the rim instead of the neck. In the context of the frieze these errors are, however, permissible variations; it would seem more interesting to consider why, of all the objects in Thorvaldsen’s collections, two antique vases were chosen for representation in the triumphal procession. For a modern observer, at any rate, these two jars might seem somewhat insignificant in comparison with the very much weightier stone sculptures, and their mode of transportation – just a trifle casual.

Vases on the Inner Courtyard Frieze

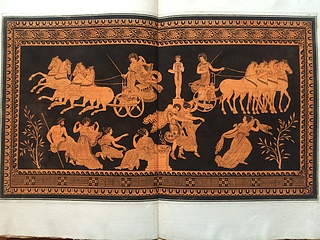

However, before looking more closely at the way in which Thorvaldsen’s period (Neo-Classicism) viewed Greek vases, we should first glance into the inner courtyard of the Museum. The photograph reproduced in fig. 5 was taken from the open double door of the transverse corridor on the first floor and shows a section of the courtyard frieze (1844-46), in which there is an even greater number of Greek vases. This time they are not being transported, but, together with a number of tripods, they are exhibited as prizes in the chariot race, in which we follow the little winged Genius and his intransigent horses through a series of falls until he finally reaches the finishing-line. The motif of Genius in a chariot race was inspired by a group of Roman children’s sarchophagi representing races in the Circus Maximus in Rome, in which Genii as charioteers undergo all kinds of dramatic experiences. There is, thus, both formal concurrence of motif and correspondence of symbolic meaning with the race track (the hippodrome) seen as the course of life.

In the Thorvaldsen Museum this idea is further emphasized by the dromos delineated in the adornment of the frieze surrounding Thorvaldsen’s grave in the courtyard, but the presence of the vases in this context is in no way required by the motif. At this point, continuing the elevated metaphor of the frieze, we can limit ourselves to noting that the vases were seen as being of sufficient value to be a reward for Thorvaldsen’s lifework. It seems clear that this must have been the intention of the frieze, even though we have no written evidence to this effect.

As opposed to the two vases in the external frieze, the vases of the courtyard frieze are not to be found in Thorvaldsen’s collection of antiques – nor are the six winged tripods. We need not seek long, however, before discovering from where their artist took his inspiration.

Their forms reveal that we are dealing with vases from the 5th-4th centuries, the Classical period. In the 18th and early 19th century, knowledge of Greek vases was almost entirely limited to vases found in burial places in southern Italy. And as most of the coveted, figure-decorated vases found there are of the Late Classical period, the 4th century B.C., it was, naturally enough, these vases that dominated the early collections that were being built up in the second half of the 18th century”.

Of the really great collections we shall mention here only Sir William Hamilton’s two vase collections, the most famous of the period. As the British Ambassador to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and therefore resident in Naples. Sir William Hamilton was optimally placed for the acquisition of new pieces for his rapidly growing collections. Both were in turn sold to England, but only after they had been published in two magnificent works that appeared with an interval of about 25 years in 1766-67 and 1791-95.

It might, therefore, be expected that the inspiration for the vases in the frieze would have derived from these two works, and in fact this seems, at least in part, to have been the case. Characteristically enough, their artist treated the originals with a considerable degree of freedom and combined form and picture without any petty regard as to what belonged to what. Thus, the Meidias hydria in London with a representation of the Rape of Leucippos’ Daughters by the Dioscuri (fig. 6) provided the chariot scene on one of the volute craters in the north frieze (fig. 7).

Fig. 7. The figure decoration of the Meidias hydria with a representation of the Greek legend of the rape of Leucippos’ daughters. The Meidias Painter. C. 400 B.C. After d’Hancarville, Antiquités du cabinet de Mr. Hamilton, vol. 1., 1766, pl. 130.

Two four-horse chariots are seen, one standing next to – and one rapidly driving away from an archaistic female statue, which forms the centre of the composition. The only difference from the original is the fact that it is laterally reversed, presumably as a result of the method of copying employed. Parallels to the cylindrical amphora-loutrophors, which appear on the south frieze of the courtyard (fig. 8a), are also to be found in the early vase collections, for instance an amphora-loutrophor that was previously in the Museo Borbonico, and is now in Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples (fig. 8b). Its highly mannered form is, however, so common in Apulia in south Italy in the second half of the 4th and the beginning of the 3rd centuries B.C. that its form alone is not sufficient indication as to the origin of the motif.

The winged tripods (fig. 9) will also prove to have been taken from Greek vase painting. There are many antique parallels to this use of the tripod. Apollo’s instrument of prophecy, as a symbol of the artist’s victory. In Athens the Street of Tripods derives its name from the tripods which victorious choric arrangers — choregs — won and paid to have placed along the street. The Monument of Lysicrates from 335/334 B.C. is an example of a still preserved choregic monument. On a high cornice a series of tripods is represented in bas-relief right round the building, interrupted only by the Corinthian capitals of the pillars. The tripods of this monument may well have furnished part of the inspiration for the courtyard frieze of the Museum, but the addition of wings to the tripods is so special that the actual representation of the motif can be ascribed only to the Berlin Painter’s hydria from ca. 480-470 B.C. in the Vatican . On an entirely identical tripod, except that it has two instead of three ring handles, we see Apollo skimming across the sea, surrounded by leaping dolphins and presumably on his way from Delos, his native island, to his main shrine in Delphi.

The Vatican hydria was found during the early excavations of the extensive necropolises of Etruscan Vulci. The excavations started in 1828-29, and in the following decades unprecedented numbers of Greek vases were brought to light. The remarkable growth at this period in the European vase collections took place mainly at the auctions in Paris and London of vases from the graves of Vulci. This source entirely superseded south Italy as the main supplier of Greek vases from the 6th and the early 5th centuries B.C., the Archaic and Early- Classical periods.

Classicism’s View on the Vases

A preliminary conclusion, based solely on the presence of the vases in the friezes of the Museum, must lead to the presumption that the two vases being transported in the triumphal procession on the external frieze must have been regarded by Thorvaldsen’s contemporaries as being of equal value with his own works; and this view is further confirmed by the way in which the courtyard frieze exhibits the vases as the very reward for the Master’s long and productive career as an artist.

In the painting of the Renaissance and of later periods antique architecture and sculpture appear at times as a primary motif — and even more frequently as a background motif to express idea or atmosphere, while antique vases are encountered far less often. In three articles published at intervals of several years, the German archaeologist Adolf Greifenhagen has analyzed a small group of paintings from the late 18th century and up to c. 1850, in which Greek vases in some way or other form part of the composition. From the Thorvaldsen collection of paintings Greifenhagen mentions three canvases with vase motifs — two flower compositions and a figure portrait.

Fig. 11. K.A. Senff: ‘An antique terracotta vase with flowers.’ Signed: ”Adolfo Senff. 1828”. Oil on canvas. 47.1×36.6 cm. B161.

One of the flower paintings (fig. 11), by Karl Adolf Senff from 1828, is of particular interest because it represents one of the vases in Thorvaldsen’s collection of antiques, a red-figure pelike ascribed to the Calliope Painter (fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Attic red-figure pelike. Boy in long cloak. Height 19.6 cm. The Calliope Painter. C.430 B.C. H608.

Furthermore, the painting might very well be the earliest flower painting with a Greek vase as part of the composition. According to Greifenhagen, this implies that idea could have originated from Thorvaldsen.

Fig. 13. A. Küchler: ‘Oberst Paulsens familie.‘ (Colonel Paulsen’s family). Oil on canvas 71.9×64.8 cm. Signed: ”A. Küchler Roma 1838”. B245.

The figure portrait (fig. 13) also has a close connection with Thorvaldsen. It depicts Thorvaldsen’s daughter and her husband, Colonel Paulsen, in an idealized family setting, occupied by well-bred pursuits or their children at play. Thorvaldsen is benignly present in the form of a portrait bust, which — though placed in the background — nevertheless occupies a central position in relation to the everyday occupations of the family. On the table in the right foreground we see Mrs Paulsen’s knitting lying next to a little black-figure Attic neck-amphora, in which a dried flower arrangement has been placed (fig. 14).

Fig. 14. Detail of painting B245, fig. 13.

Greek vases in connection with figure portraits and flower compositions represent the two main groups within the particular kind of painting collected by Greifenhagen. Both groups tell us something important about contemporary attitudes to Greek vases; flower compositions in which vases are decorative objects; figure portraits of princes and businessmen, scholars, artists or art-lovers, who demonstratively or more discreetly, purely en passant as it were, draw attention to the cultural interests dear to them. It must be admitted that Küchler’s juxtaposition of the knitting with the Greek vase expressses extreme restraint. This peaceful idyll points, not without irony, to a characteristic aspect of the Danish Golden Age.

It is clear that in neither of the two kinds of painting is there any immediate correspondence to what seems to have motivated the choice of the vases for the friezes on the Thorvaldsen Museum. And yet it is in the portrait group, ending in the intense Biedermeyer of the Paulsen family portrait, that we shall find an unambiguous statement about contemporary attitudes, which is in closer accord with our immediate impression of what the friezes of the Museum would seem to be saying on the subject. Once again we are dealing with a double portrait, this time one of the earliest representatives of the group, John Singleton Copley’s portrait of the American married couple Mr and Mrs Ralph Izard painted in Italy in 1775 during their Grand Tour (fig. 15).

Fig. 15. J.S. Copley: ‘Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Izard.’ Oil on canvas. 175.3×224.7 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

In the background Copley has placed the ruins of the Colosseum, and in the left middle ground a red-figure volute crater from c. 450 B.C. with a representation of Artemis and Apollo sacrificing on a lighted volute altar (fig. 16). Finally, on the right, we see a group that was highly admired at the time, the antique pastiche of Orestes and Electra from the 1st century A.D. The figures reappear, moreover, on the drawing with which, presumably as a memento for their portfolio, the married couple are so significantly occupied.

Fig. 16. Detail of painting reproduced in fig. 15. Attic red-figure volute crater from c. 450 B.C. The figure decoration represents Apollo and Artemis at an altar.

It is the presence together of the three types of antique monument — architecture, sculpture and painting – that is of interest here. It was entirely natural for the Neo-Classical period to employ antique monuments as representatives of high art. But the representation of painting by a Greek vase, instead of, for example, by a Pompeian mural, is in the very language of painting — an unmistakable statement: the vase is seen as being of equal value with Greek monumental painting. Indeed, it is in a sense, actually Greek painting, which had been rediscovered through the many recent finds of Greek vases.

Of the approximately 30 known paintings from this period in which Greek ceramics appear as a motif, Copley’s is the only painting prior to the friezes on the Thorvaldsen Museum to tell us so unequivocally how the representations of the Greek vases should be understood. Of course, the Copley painting sheds new light on some of the other portraits in the group and suggests, at any rate in some cases, that it is matters sublime, rather than mere pottery, to which these grave gentlemen have devoted themselves. If this is the case, then there must be a connection between Copley’s painting and Sonne’s frieze executed three-quarters of a century later. If, as is possible, however, Sonne’s inspiration occurred independently, then the only connection will be that which thoughts thought in the same period quite naturally possess.

Bindesbøll’s Ideas for the Friezes

It has often been claimed that the friezes were originally conceived by the architect of the museum M.G. Bindesbøll. Although it is probable that the painters Johann Scholl and Jørgen Sonne, who executed the courtyard frieze and the external frieze respectively, contributed ideas and added a number of details to the composition, the realisation of the project took place within the framework established by Bindesbøll. The unusual and severely reduced palette, which characterizes the friezes, is clearly taken from red-figure vase-painting, and there can be little doubt that so important a feature in the long-planned polychromy of the building was projected by its architect. It would seem to provide interesting testimony regarding the extent to which Bindesbøll shared the views of his time on Greek vase-painting. It must have been this genre he had in mind when, in a letter written during his tour of Greece (1835-36),

Bindesbøll compared an event he had observed in the streets of Athens with scenes on ”old paintings”: ”An old fellow sat by the fire and poured wine into pots from a large goatskin wine sack. The young people once again sprang round in a circle, but with jubilant merriment, held the pots up in the air, poured, danced and shouted … just like bacchants in old paintings.” Bindesbøll does not seem to have come any closer in writing to formulating the view to which he gave such monumental expression in the friezes on Thorvaldsen’s Museum.

That it was the red-figure and not the black-figure vase-painting that was chosen as the inspiration for the friezes is in complete agreement with the contemporary view of the former as the Perfect, the Beautiful, while the latter was regarded as primitive or, at best, as not fully developed. Correspondingly, there is a considerable predominance of red-figure vases in the already mentioned group of paintings, portraits or flower pieces in which Greek vases appear. It is true that on the friezes of the Museum the vases are represented with black figures on a light background, thus reflecting the colours used in black-figure vase-painting, and this would appear to be in conflict with the preference discussed above. It is, however, normal when vases are represented within red-figure vase scenes for the former to be reproduced as black-figure or, more precisely, silhouette-decorated pottery, since a vase contour reproduced in the red-figure technique and placed against a black background would be entirely swallowed up by it. The presence of the black-figure vases on the friezes is not, then, the product of a free decision to be different, but is based on the conditions of red-figure vase painting.

Bindesbøll’s Showcases

In the following we shall consider an aspect of the Museum’s internal arrangement which no less clearly shows how Bindesbøll regarded and used antique vase-painting.

Thorvaldsen’s antique collection is housed on the first floor in the side rooms of the south wing. Its division into bronze, gem, coin, sculpture and vase rooms accords exactly to the way in which other antique collections were arranged at the time. The vases are classified on an equal footing with the other antiquities.

The arrangement of the collections was also worked out by Bindesbøll, who drew designs for furniture and exhibition cases, made a plan for the furnishing of the entire suite of rooms and on a cross section of the south wing sketched in, among other things, a show case for vases, which illustrates how the vases are to be arranged (fig. 17).

An article in Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum 1948 by Professor Mogens Koch contains a detailed analysis of Bindesbøll’s furniture in the Thorvaldsen Museum. Koch gives an account of their carefully thought out and superbly disciplined design, the subtle choice of materials and the excellence of their craftsmanship. Particularly interesting for our purposes is, of course, Koch’s analysis of Bindesbøll’s show cases for vases (fig. 18).

Fig. 18. The Vase Room. The Thorvaldsen Museum.

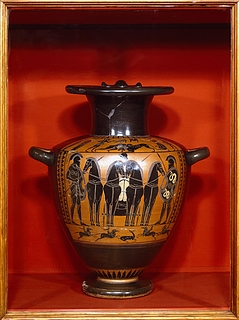

There are four show cases in all: two large double cases with sliding doors are placed along the sides of the vase room. They contain black-figure Corinthian and Attic ceramics, Etruscan bucchero and black-glazed pottery and various odds and ends. The Attic and Southern Italian red-figure pottery is placed against the end wall of the room, and it is on these cases that the eye first falls. The two cases have prominently marked top profiles and hinged doors.

Common to all four cases is the division of the doors into three times three glass panes. The shelves inside the cases have been placed so as to ensure that the exhibited objects receive optimal lighting through the panes. A closer study of the placing of the vases, both in the cross section drawing of the south wing (fig. 17) and in the actual exhibition (fig. 19) reveals the application throughout of one simple principle.

Fig. 19. Section of M.G. Bindesbøll’s exhibition case in the Thorvaldsen Museum.

For each pane there is a vase arrangement. The principle appears in its purest form in the sketch, where each pane contains a single vase, while in the actual exhibition it was as a rule necessary to place a number of vases within the space corresponding to an individual pane.

The underlying idea is clearly that each space is intended to contain its vase or vases as an oil painting is limited by its frame. And placed close together, side by side and row by row, the positioning of the vases corresponds to the exhibition practice of the period, in which paintings patterned the walls vertically and horizontally in close formation.

Fig. 20. Individual pane in section of exhibition case reproduced in fig. 19. The Attic black-figure hydria is ascribed to the Antimenes Painter. Height of vase: 48.2 cm. C.520 B.C.

A contemporary parallel to this principle was to be found in the vase collection in Munich. Here in 1841 Ludwig I’s vases, which had been collected since 1824, were, with the assistance of the painter and sculptor J.M. Wagner, exhibited in Die Alte Pinakothek”. The idea was that on the ground floor the vases together with the collection of antique mosaics were to give the proper historical introduction to the museum’s collection of European Old Masters. The other antiquities were kept quite separate from the vase collection and were exhibited in Hofgartengebaüde in 1844 as Die Vereinigten Sammlungen Ludwigs I.

Post-Antique restorations are removed

For changes to be made in a so highly esteemed exhibition as Thorvaldsen’s vase collection particularly good arguments are, of course, required. These seemed to be present when in 1971 the Museum was invited to have its vases published in the international Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum. This work, which began to appear in 1922 and today numbers more than 200 volumes, aims at the complete publication, museum by museum, of all known antique vases. According to the new guidelines for publication in the series it is required that all post-Antique restoration in the form of over-painting and the addition of missing parts should be removed insofar as they disturb the proper understanding of the vase.

It cannot be denied that the antique vases, excavated and acquired by museums in the last century, are often heavily restored. It was, therefore, with some anxiety that the Museum placed the first vases in water in order to get an idea of how much was antique and how much modern. Would we end up with a heap of fragments, which could only cohere with the help of the 19th century’s plaster filler, specially fired ”fragments” or filed antique shards?

Today when practically the whole collection has emerged from the water, the fragments freed from any modern over-painting and the antique parts reassembled (fig. 21), we can with no little relief conclude that Thorvaldsen acquired well preserved vases that could be exhibited without later reinterpretative restoration. In a few cases there is only one entire and presentable facade left for exhibition, while one or two vases are in such bad condition that they have had to be placed in storage.

One of the vases that survived the new process of restoration so well that it could still be exhibited, though in much reduced form (fig. 22-23), is one of the two vases being transported on Sonnes frieze (figs. 1 and 3). In our recreation of the 19th century arrangement (fig. 19), the vase is to be found on the second shelf, on the left. Furthermore, the photograph documents with what reverence the ”surgical” operation was carried out. Although all additional material has, in principle, been removed, we have preserved and stored so much that if posterity should wish to restore the collection to its original appearance, then this will be possible.

Figs. 22. Attic black-figure hydria, shown in fig. 2, after restoration. Present height: 27.8 . H573.

Although we do not wish to make excuses for our ”operation”, we would maintain that today’s visitor to the vase collection receives the same impression as that aimed at by Bindesbøll when the exhibition was arranged almost 150 years ago. There has been no breach of his principles in the new arrangement although some vases may have been moved because their new condition means that they can no longer be seen to advantage in their former placings. Our old, now somewhat lame water jar (figs. 22-23) has moved up a shelf, so that instead of looking down into a ruin, we look directly into a vase picture. But even though the vase is, to use an archaeological term, no longer in situ, it has nevertheless been placed according to the original principle.

Besides the principle of central positioning in relation to the light of each pane, the following two main guidelines continue to apply: as the overriding principle, and in accordance with the idea of a gallery, arrangement by genre – gods, heroes, everyday scenes, etc., — and an attempt at creating a harmonious whole within the individual shelf from the various heights of the vases. The effect aimed at is that of pyramid and festoon, in which the rims of the vases seen together form sloping or arching sequences.

New Discoveries

The next question that arises, and the last we shall consider here, must be whether the whole process was worth so much effort, time and money. If I would tend to answer this question in the affirmative, that is not because this is the expected answer on such an occasion. During our work with the vases several interesting and unusual details have come to light, which are informative both about Antiquity and about the attitudes of the 19th century to Antiquity — and to itself.

An account of individual cases would furnish almost enough material for a new article. We shall limit ourselves here to mentioning the kinds of detail encountered. There are cases in which inscriptions with information about the market value or the volume of the vase had been partially or entirely concealed beneath layers of supporting plaster. And there are traces of antique restoration, riveting, which tells us something about the value the individual vase had in Antiquity, but which the restorers of Thorvaldsen’s time covered, no doubt also because riveting was a banal matter for them, but primarily because they wished to see Antiquity as complete and whole as possible and shrank from exhibiting it as fragmented. By way of contrast, the present age, in which an entire generation has been largely brought up to have a use- and -throw-away mentality, we uncover the traces with pleasure.

Finally, mention should be made of an Attic drinking bowl; the holes bored in it in Antiquity had been filled with plaster and painted over, because the holes were simply seen as yet another example of riveting. In recent years such bowls have been recognized to be antique practical jokes. The idea was that in the midst of the festivities one of the members of a merry company should be sprayed with the contents of the bowl to the accompaniment of roars of Homeric laughter from the drinking companions lying around him.

All this and much more would have remained concealed, had we not chosen to purge the vases of their 19th century restoration.

Last updated 11.05.2017