The Impact of Italy on Danish Music

- John Bergsagel, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 1997

This is a re-publication of the article: John Bergsagel: ‘The Impact of Italy on Danish Music’, in: Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum (Communications from the Thorvaldsens Museum) p. 1997, p. 154-160.

For a presentation of the article in its original appearance, please see this facsimile scan.

“Italia! oh Italia! thou who hast

The fatal gift of beauty …

Mother of Arts! .. . ”

exclaimed Lord Byron in Canto IV of Childe Harold and invited “the orphans of the heart” to turn to Rome:

“ … Come and see

The cypress, hear the owl, and plod your way

O’ er steps of broken thrones and temples. Ye!

Whose agonies are evils of a day -

A world is at our feet as fragile as our clay.”

When he wrote these lines, which are inscribed on the base of the Roman copy of the statue Thorvaldsen carved of him in 1817, he had already been anticipated by C. W. Eckersberg, who the previous year had returned to Copenhagen after having spent three years in Rome. Eckersberg too had been overwhelmed by the ancient capital and found that for “the innumerable quantity of magnificent works of art, monuments of antiquity, churches, districts and other things of interest, I must admit that Rome is certainly in this respect the First City.” One after the other Eckersberg’s pupils at the Academy of Art in Copenhagen, the painters who, with their teacher, were to be acclaimed as contributing to their country’s “Golden Age”, were sent, as the most natural thing in the world, in their master’s footsteps.

Hans Christian Andersen claimed that it was in Italy, “whose atmosphere has a heavenly light”, that he “learned to know Nature and Art [in the] beautiful land of colours and forms”, and at the end of the century Italy still retained its magic for writers. In 1891, when the young Norwegian poet Vilhelm Krag called on Henrik Ibsen, recently returned to Norway after 25 years in exile, he was asked what he intended to do with the Houen Stipendium that the great man was going to help him get. Krag provocatively proposed to travel to Tunis, where he would buy a white horse and ride out into the desert, to which Ibsen, when he had recovered from the shock of this levity, expostulated: “No, you are not going to travel to Tunis. You are going to go to Italy. A young poet has to go to Italy.” Then, Krag relates in his memoir Dengang vi var tyve aar [When we were twenty],” he explained why. For more than an hour and a half Henrik Ibsen sat and told the young poet what he should do when he came to Italy. Later I followed his advice; I planned my trip and my work in Italy as Henrik Ibsen had counselled me. I don’t regret it …” We are not told Ibsen’s explanation of the importance of Italy to a young poet, but it scarcely matters; also in respect of writers it seems somehow self-evident that a period of residence in Italy ought to be beneficial.

“Italy, mother of the arts”, said Byron: is not Italy then also the home of music? Of course it is. Had not Christian IV sent his most promising musical talents to study with Gabrieli in Venice in the years around 1600? Were not Corelli and Scarlatti extolled by Holberg, and had it not been customary throughout Europe in the 18th century for musicians to emulate the Italian style, as Handel and Mozart had done? In the 19th century, however, the language and expression of German Romanticism began to challenge the dominance of the Italian style and Germany became a tempting – and for Scandinavians convenient – alternative as a place to go to learn their craft.

From the founding of the conservatory in 1843 Leipzig became music’s Mecca. Composers, such as Heise and Grieg from Scandinavia, still went to Italy, of course, but for Italy’s own sake – it was, after all, without question the home of the arts – after first having studied in Germany.

As Grieg wrote in 1871: “Life here has given me an endless series of impressions that it would be useless to try to describe. In Rome I found peace in which to think more deeply about the greatness around me, the daily influences of a world of beauty. A northerner has in his national character so much that is heavy and reflective which in reality never gets any counterbalance in the exclusive study of German art … A freer and more all-round view of the world and art as a whole develops down here and I consider it my duty therefore to recommend as warmly as possible that young artists who have acquired the technique of their art should have a stay there.”

At first it was especially in instrumental music that Germany established its preeminence: “We have no symphonies, quartets, or quintets, which can rival the works of the German school,” complained the English critic and historian George Hogarth, father in-law to Charles Dickens, in 1838. “ [English composers] have to contend with the stupendous works of the German masters, the excellence of which appears to the public, as well as to themselves, to be unapproachable.” In the field of singing and opera, and also violin playing and violin building, however, Italy maintained a special position as guardian of a tradition that was able to withstand the challenge of transalpine rivals during the course of the century.

It is not surprising, therefore, that one of the Scandinavians who derived particular benefit from Italy in the early 19th century was a violinist – the violinist – Ole Bull. Having heard Paganini in Paris, he went to Italy in 1833, had his artistic breakthrough in Bologna, visited Naples, and in Rome sat under a full moon in the Colosseum and improvised on his violin from midnight “until the golden bands of dawn greeted the dome of St. Peter’s; what I felt! ... pain; an endless longing for an unobtainable goal!” He spent three months in Rome in the company of Scandinavian writers and painters, sharing rooms with the Norwegian painter Thomas Fearnley. During this time he completed the composition of his Recitativo) Andante amoroso con Polacca Guerriera, which he had begun in Naples, inspired, he later said, by an eruption of Vesuvius. It became his most frequently performed piece – not least, one supposes, because of the volcanic fireworks of the ending, the musical counterpart, perhaps, of one of the paintings on this theme by his countryman, J.C. Dahl. (fig. 93).

Fig. 93. J.C. Dahl: Vesuvius in eruption, 24 December 1820

Oil on canvas, 43×67.5 cm, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Bull wrote other pieces on Italian subjects, notably a brilliant Fantasy and Variations on a theme of Bellini for violin and orchestra, which is one of the only three compositions he published in his lifetime. However his music was so inextricably bound to his own performances of it that it does not appear to have exerted any lasting influence on Scandinavian music, however brilliantly and energetically he himself may have represented Norway and Scandinavia on the international scene.

Before he learned the Italian style, Bull’s idol had been the German violinist and composer Ludwig Spohr, whom he had set out to meet in 1829. For that journey, he told his father, “in Copenhagen I have gained a travelling companion, a Herr Frølich, Singing Master in the Royal Danish Theatre, who can be of great help to me. He is a pupil of Wexschall, plays a good violin, but in particular is a clever theorist, a good composer, a young man of twenty-something. He will be travelling abroad for 2 1/4 years in Germany, Switzerland, France and Italy ...” J.F. Frøhlich arrived in Rome in 1830 where he spent the better part of a year in the company of Thorvaldsen, Bissen and Ludvig Bødtcher. Though Bull describes him as a good violinist and a composer, his main purpose in going to Rome was perhaps to study singing and to further his experience of opera in connection with his position as “Singing-master” at the Royal Theatre, to which he returned in Copenhagen in 1831. In 1838, convalescing from a serious illness, he made another trip to Italy on the frigate Rota that was sent to bring Thorvaldsen home to Denmark. It is said that this trip gave inspiration for the ballet Festen i Albano that he wrote for Bournonville in 1839. As was the case with Ole Bull, the impact of Italy came to at least superficial expression also in other compositions, such as his Souvenirs de Rome, Op. 31, composed in 1830, but the most important product of his stay in Italy is undoubtedly his Symphony in E flat, Op. 33, which he completed in Rome on September 9, 1830. This is a major work in a genre that was virtually uncultivated in Denmark at that time. That it should have come into existence in Italy is rather unexpected – perhaps the inspiration to try his hand at a symphony had come during the earlier stages of his trip, in Frankfurt, perhaps, or Paris. Nevertheless, when he wrote to his sister from Rome on 11 August 1830, he said that he had “now begun work on a big symphony, of which I hope to finish the first Allegro in this week”, and the work was certainly completed in the following month in the heat of the Roman summer. Sven Lunn regards it as “a thoroughly personal work”, but, not surprisingly, considers that Beethoven, Weber and Kuhlau have stood as god-parents at its baptism. Be that as it may, I wonder if an Italian tone has not insinuated itself into Frøhlich’s inspiration In the charming, light major melody which breaks in to relieve the dark and rather heavy mood of the second movement. (fig. 94)

Fig. 94. J.F. Frøhlich: Symphony in E flat, 2nd mov’t. Andante.

If I am right in feeling this to be perhaps an unconscious reaction to the musical environment of Rome, it is a more subtle response to Italian influence than that represented by the choice of a visual subject or the reworking of a theme of known associations, since here at least it has been absorbed into his personal style. The symphony had to wait until 1833 for a performance and then it was given in two parts, the first and third movements at the start and the second and fourth movements at the end of a concert of very mixed content. In 1834 he was put in charge of conducting opera performances, but Frøhlich’s career was destined to be short and his influence on Danish music as a composer limited by the subsequent neglect of his music: he resigned his post at the Royal Theatre in 1844 and lived a life of increasing isolation, eventually unable to compose, until his death in 1860.

After Frøhlich, the only Danish composer of significance to visit Italy during what has been designated for the purposes of this symposium as the “Golden Age period”: that is up to about 1850, would appear to have been Niels W. Gade, who in 1844 proceeded to Italy from Leipzig and in Rome received an invitation to return to Leipzig as conductor of the Gewandhaus orchestra and teacher at the conservatory. This was purely a tourist trip, however, which seems not to have left any direct traces in his music – his contribution (Act 2) to Bournonville’s ballet Napoli had already been made in 1842.

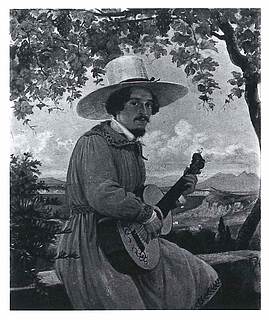

Fig. 95. C.A. Jensen: Portrait of Rudolf Bay, Rome 1819.

Oil on copper. 23×16 cm. Private collection.

Among lesser composers, Rudolf Bay was one on whom Italy made an impression of lasting duration. It is not entirely clear if he had any particular purpose in mind when he went there on a two-year leave from his duties as consular secretary in Algiers in 1819-20, but as a talented musical dilettante he took the opportunity while there to study composition and singing. The three volumes assembled from his letters and papers that were published in 1920-21 give a lively picture of life and music in Italy, especially Rome, at this time and at a later visit in 1842-3, and of his own active part in it. His association with Danish “Golden Age” artists in Rome is documented by C.A. Jensen’s portrait of the young consular official painted in 1819 (fig. 95) and by a caricature drawing of the musical entertainer performing to the enthusiastic applause of Danish artists in Rome done by Constantin Hansen during Bay’s second stay in 1842-3 (fig. 96).

Fig. 96. Constantin Hansen: Caricature drawing of Rudolf Bay performing in Rome.

230×160 mm. Private collection.

The songs that Bay published in Copenhagen from time to time appealed very much to the taste of the times so that his name was not unknown when he returned from abroad to settle in Copenhagen in 1831. He was appointed cantor at Holmen’s Church in 1834 and made titular professor of the university in the same year – perhaps, one may suspect, promoted by the Italophile Prince Christian Frederik (the later Christian VIII). The taste for things Italian of this Prince, who had also supported the Norwegian painter Johan Christian Dahl’s stay in Italy in 1820-21, had caused him to bring Giuseppe Siboni to Copenhagen in 1819 to teach singing at the Royal Theatre. When Siboni died in 1839 (the year in which Prince Christian succeeded to the throne), Rudolf Bay aspired to be his successor, but without success. Bay had a considerable experience of Italian music and was in a position to further its cause at a time when there was a growing interest in it in Denmark.

It no doubt prompted his efforts on behalf of improving singing in church and home, which included a book Om Kirkesangen i Danmark og Midlerne til dens Forbedring [On Church-singing in Denmark and the means to improve it] but as a composer his contribution was and is limited to some much-appreciated songs.

The successful applicant for Siboni’s position as Singing-master at the Royal Theatre in 1839 was Henrik Rung (1807-72), who perhaps therefore receives a rather sharp and on the whole condescending treatment in Bay’s account of the present state of music in Denmark in his journal from the late 1840s. Rung was a member of the Royal Orchestra as contrabassist when in 1835 he made his debut as composer. After arranging music for some vaudevilles, he had a notable success with his music to Henrik Hertz’s play Svend Dyrings Hus, which resulted in a travel grant for two years of study abroad. He seems already at this time to have decided to prepare himself for Siboni’s job, for on arrival in Rome he began at once to take vocal training from Girolamo Ricci, a prominent teacher, who introduced him to Rome’s musical life and institutions. Already early in 1838 he could write home to Denmark: “I feel more and more each day the beneficial effect a stay in Rome has on a musician. Every Sunday and holiday I am able to hear the papal choir perform excellent compositions. I have also been so fortunate as to obtain entrance to the most famous library in Rome, where I occupy myself with the study of church compositions; this is especially interesting, since the music as well as the style in which it is written is virtually unknown to us [in Denmark] ... ” The library referred to here was apparently the private library of the Abbe Santini, but he was also introduced to Giuseppe Baini, the pioneer in the revival of interest in the music of Palestrina, who gave him access to the Vatican Library itself.

Fig. 97. Wilhelm Marstrand: Portrait of Henrik Rung. 1838. Oil on canvas.

He became involved in the movement to rediscover the music of the past, especially Italian music of the 16th and early 17th centuries, and copied a valuable library of music which at that time was, of course, quite unavailable in modern editions. At the death in March 1839 of Siboni, both Ricci and Baini wrote letters in support of Rung’s successful application for the position of Singing-master. It was agreed that this appointment should take effect from the autumn of 1840 and his leave from the theatre was accordingly extended by another year.

In Rome he was, of course, a member of the Scandinavian Society and organized its musical activities. Among the music-interested members were the painters Wilhelm Marstrand, who painted a portrait of Rung in Italian costume with his guitar (he was also a virtuoso guitarist) in 1838 (fig. 97), and Jørgen Roed.

These friends, with their musical wives, continued to meet when all were back in Copenhagen, nurturing their love of Italy with the singing of Italian music. Marstrand has left a charming drawing of such a gathering at Roed’s home, presumably in 1848, with Rung leading the singing from the piano (fig. 98).

Fig. 98. Wilhelm Marstrand: A group singing, led by Henrik Rung at the piano, in the home of the painter Jørgen Roed in Copenhagen, c. 1848. Drawing. Private collection.

At the Royal Theatre he was given the responsibility for training opera singers in the Italian style, a work that coincided with a public enthusiasm for Italian opera generated by the opening of an Italian Opera Company in the new Vesterbro Theatre in 1841. At the same time he took every opportunity he was given to introduce the older Italian music into concerts of Musikforeningen [the Music Society] and later of Den Skandinaviske Sangforening [the Scandinavian Singing Society]. Finally he felt the time was ripe to found a choir which, according to the statutes, had as its purpose “to make classical Italian church music of an older period, specifically the 16th and 17th centuries, more widely known than hitherto to lovers of good music.” The name of the choir was to be Cæciliaforeningen [the Cecilia Society].

The Society did not, in fact, hold itself strictly to this declared purpose, since it included in its programmes both secular music, music by non-Italians and music by modern composers, such as Weyse and Henrik Rung himself, who composed several pieces to Latin and to Italian texts by such poets as Dante, Petrarch and Ariosto. Some of his pieces to Danish words too seem to be attempts to create a kind of Danish madrigal style, such as a piece for 8 voices that he called an “Aphorism”, which appeared on a programme in 1868. However, especially as long as Henrik Rung himself lived and directed the choir, the programmes of the Society show an impressive effort to realize its objective, which included also the publication of editions from Rung’s large library of copies from Italian libraries.

As a young student Thomas Laub (1852-1927) was often in Rung’s home, where he could become acquainted with this treasure, and in 1882-3 he followed Rung’s example and made a research trip to Italy where he copied music from manuscripts and early prints in Italian libraries. Laub became one of his time’s best authorities on the polyphonic style of 16th-century a cappella music. He in his turn was acknowledged as the teacher to whom Knud Jeppesen (1892-1974) was most indebted in determining his development as a scholar – as Carl Nielsen was in shaping his career as a composer. Jeppesen’s doctoral dissertation on Palestrina’s style in 1922, and the text-book for teaching 16th-century counterpoint derived from it, together with his remarkable discoveries and studies of Italian music of the 16th century in particular, have been of central importance to our present-day understanding of Renaissance music.

After Henrik Rung’s death in 1871 the leadership of the Cecilia Society was taken over by Holger Paulli for an interregnum period until, as it was agreed, it could be assumed by the founder’s son, Frederik Rung (1854-1914), in 1877. Under his direction oratorios and other large works for chorus and orchestra were added to the Society’s original repertoire. He was succeeded in 1914 by his nephew, P. S. Rung-Keller (1879-1965), and finally, in 1931, by Mogens Wøldike (1897-1988), until its activites ceased in 1934. Before that, however, in 1922 Wøldike, who like Jeppesen was a pupil of Carl Nielsen and Thomas Laub, had been asked to take over a choir which had been formed to perform, at the request of the Danish-Italian Society, Palestrina’s 6-part Missa Papae Marcelli in its entirety. Though movements of this famous mass had been sung from time to time on the programmes of the Cecilia Society, it had never been performed altogether. This took place at a concert in 1923 introduced by Knud Jeppesen and the choir continued its existence under the name the Palestrina Choir. Like the Cecilia Society, it too ceased to exist in 1934 and its work and music library here taken over by the Copenhagen Boys’ Choir, founded by Mogens Wøldike in association with a proper song-school. This choir and school still exist and occupy a place of great importance in Danish musical life.

The impact of Italy (as opposed to Italians) on Danish music was limited in the Golden Age by the fact that no Danish composer of first rank was subjected to it. However, it was felt in some degree by various Scandinavian musicians and absorbed in full measure by at least one, whose response was extended to include something we might today call practical musicology. In this way the musical public in Denmark was privileged in an unusual degree to become acquainted, earlier than many others, with a rich repertoire of music recovered from the past. That work has continued in an unbroken tradition to enrich both Denmark and the world at large down to the present day.

Last updated 11.05.2017