Some Recent Acquisitions

- Stig Miss, Eva Henschen, Gertrud With, Thomas Lederballe, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 1997

This is a re-publication of the article:

Miss, Henschen, With, Lederballe: ‘Some Recent Acquisitions’, in: Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum (Communications from the Thorvaldsens Museum) p. 1997, p. 181-188.

For a presentation of the article in its original appearance in Danish, please see this facsimile scan.

- 1. Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg: Portrait of Bertel Thorvaldsen, 1820

- 2. Bertel Thorvaldsen: Venus with the Apple

- 3. Joachim Ferdinand Richardt (1819-1895): Thorvaldsen in his Studio at Charlottenborg, 1840-1842 Thorvaldsen Sketching, 1840-1842

- 4. Bertel Thorvaldsen: Tomb of the children of Helena Poninska,1835

- 5. Puk Lippmann: Rug

Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg: Portrait of Bertel Thorvaldsen, 1820

Oil on canvas. 49,7×40 cm. Inv. no. B454.

In November 1993, Eckersberg’s painting of Thorvaldsen was offered for sale at the Kunsthallen auction no. 434. The painting was sold to a private foreign buyer, but it was immediately bought back by the Commission on Export of Cultural Assets, as it was considered to be a valuable part of the Danish cultural legacy and thus covered by the “Act on the Protection of the Danish Cultural Heritage”. In January 1994 the painting was then placed in Thorvaldsens Museum.

The painting portrays Thorvaldsen seen obliquely from the front. He is simply dressed in a dark coat with a white, open-necked shirt. Apart from his face, all that is visible is his right hand. Four elements in the picture suggest his profession, his identity and Eckersberg’s special view of him.

The foot of a marble sculpture can be seen on the left, and this together with the hammer on which Thorvaldsen’s right hand is resting indicate that we have a sculptor before us. The sculpture cannot be identified among Thorvaldsen’s works, and Eckersberg has obviously not found it important to reproduce a specific piece. The portrait was painted while Thorvaldsen was in Copenhagen between October 1819 and August 1820. It is possible to pinpoint the exact date on which the portrait was completed, Eckersberg noting in his diary on 12 May 1820 that he has “Finished the portrait of Thorvaldsen”. During his stay in Copenhagen, Thorvaldsen only executed portrait sculptures and a few reliefs for the Cathedral, Vor Frue Kirke, and he did not work in marble at all.

Thorvaldsen is wearing his antique gold ring in the shape of a snake on the little finger of his right hand. He wore it for many years both in Rome and in Denmark. He was often portrayed wearing the ring, but for the sake of the composition of his painting Eckersberg has moved it from its usual place on the ring finger of the left hand.

Finally, of course, the painting is a true likeness, and in depicting the face Eckersberg has gone to great pains to emphasise the pale, grey-blue sharp eyes. They constitute the living, changeable element which contrasts with Thorvaldsen’s generally relaxed, contemplative appearance. It is precisely here that Eckersberg’s portrait relates to the one which he did of the sculptor in Rome six years earlier. Here, Thorvaldsen is also presented as sitting quitely, almost slumped, in the habit of the Accademia di San Luca before a section of what at that time was his greatest artistic achievement, the relief frieze The Entry of Alexander the Great into Babylon; this had been created to decorate a chamber in the Quirinal Palace in connection with the expected arrival of Napoleon I in Rome in 1812. And in this painting, too, the eyes are alert, vibrant and shown reflecting a light coming from outside.

In both portraits, Eckersberg thus maintains his own view of Thorvaldsen, which seems to be in keeping with dominant features in a great many of Thorvaldsen’s sculptures: restrained, contemplative, introspective qualities. This view of Thorvaldsen is very different indeed from that in many others of the over 100 portraits of Thorvaldsen that are known, some of which portray the sculptor as dynamic and extrovert, while others, making use of dress, a grandiose setting or monumentality, focus on the distinguished public image, on Thorvaldsen’s illustrious reputation.

Eckersberg’s portrait is seen to be the portrait of a friend, a painting of someone on equal terms with the person portraying him. Eckersberg had the right background to be able to do this, as he had become a close friend of Thorvaldsen during his three years in Rome from July 1813 to May 1816. Eckersberg lived in the same house as Thorvaldsen, the Pensione Buti in the Via Sistina, and he benefitted from Thorvaldsen’s inspiration in fashioning certain figures in some of the paintings he executed in Rome. And Thorvaldsen also had a quite tangible significance for Eckersberg in constantly lending him cash while the painter was waiting for his scholarship money to be paid out.

Shortly before Eckersberg’s departure from Rome, Thorvaldsen did a portrait bust of him.

It is not known whether or not this portrait was a commission, but the painting must subsequently have come into the possession of the Fine Arts Association. The Copenhagen Fine Arts Association was founded in 1825, and one of its important functions was to buy or commission works of art, which were then disposed of by lottery among the members. In january 1838 a certain Rev. Riis was the fortunate winner of Eckersberg’s portrait of Thorvaldsen. Later, the painting passed through the hands of various private owners until it was offered for sale on the art market in 1993. In November 1820 the engraver J.F. Clemens finished an engraving based on Eckersberg’s portrait, and Thorvaldsen must have known about this before leaving Copenhagen in August that year. At Thorvaldsen’s request, Clemens sent 50 copies of the engraving to Rome in luly 1821.

A painted replica of the portrait, done by Eckersberg himself, was in 1855 bequeathed to Thorvaldsens Museum, being placed in the Museum in 1871 (Inv. No. B419). However, this painting has nothing like the same artistic value as that which has now been acquired.

Stig Miss

Fig. 110. Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg (1783-1853): Portrait of Bertel Thorvaldsen, 1820. Oil on canvas. 49,7×40 cm. Inv. no. B454.

Bertel Thorvaldsen: Venus with the Apple

Marble. Height 90,6 cm. Inv. no. A916*

In 1994, by an accident of fate, Thorvaldsens Museum had the opportunity to acquire a small version of Thorvaldsen’s Venus statue done in marble by the sculptor’s own hand.

When it was bought, the statue was in a fairly poor condition, having sustained damage both at an early date and more recently. The latter had resulted from the marble apparently having been exposed to the elements for a time.

Thorvaldsen’s Venus is one of the works which have most frequently been copied. It was being produced in many versions, both a large and a smaller variant, even in Thorvaldsen’s own day.

The very first Venus by Thorvaldsen was in the smaller format and was modelled in 1804 for Countess Irína Ivánova Vorontsóv. The next Venus, which was modelled life-size 1813-16, was thus in principle a kind of enlarged copy of the smaller Venus statue.

In addition to these two, many more were produced for buyers all over the world, and several have since ended in the possession of people unknown to us. It was therefore some time before the earlier history of the Museum’s new acquisition became more or less clear.

The English art historian Ronald Lightbown has kindly helped with some of the details relating to the story.

The first time this figure appeared in the annals of the Museum was in 1920. Thorvaldsens Museum was then contacted by a Mrs Marten of Marshalswick, England, who was offering to sell a small Venus to the Museum. The figure was accompanied by reliable documentation of its having been “done by his own hand” (i.e. in Thorvaldsen’s workshop) in the form of written agreements with Thorvaldsen concerning the original purchase. This document now appears to have been lost.

Meanwhile, the Museum refused the offer on the grounds that that very year it had acquired another larger version of the Venus, done in marble by Thorvaldsen’s workshop for P.C. Labouchère in 1828.

The next time this small Venus came to figure in the Museum’s correspondence was in November 1934, when it had been offered for sale at Sothebys in London by Mrs Marten.

Luckily, the auction catalogue was furnished with an excellent photograph. This showed some very characteristic holes and knots on the tree stump, something that subsequently was crucial to the final identification of this version.

From the text in Sotheby’s catalogue it was clear that the sculpture had been bought direct from Thorvaldsen by Charles Daniel Nevinson of 49 Montagu Square, the Court Physician to George III.

The sale of the statue in 1934 gave rise shortly afterwards to an article in Danmarks Posten, in which reference was made to details in the family’s correspondance with Thorvaldsen. Among other things, it was stated that the statue was originally intended for “Copenhagen Museum”, but that Dr Nevinson had persuaded Thorvaldsen to sell it to him for 300 guineas.

It must be assumed that this is the same Dr Nevinson who in Else Kai Sass’ book Thorvaldsens portrætbuster is referred to as having acquired a copy of the relief of The Three Graces.

Dr Nevinson was an art collector who travelled a great deal, and everything suggests that be bought these things of Thorvaldsen at the end of the 1830s.

Dr Nevinson’s sister or daughter (?) had married into the Marten family of Marshalswick in 1800, and consequently the statue of Venus remained in the possession of this family.

At the 1934 auction at Sotheby’s, the Venus was bought by the London Consul General, Frantz Hansen, and his son later took it over. In 1949 the statue was again sold by the antique dealers Spink & Son.

When the small Venus again appeared at a Sotheby auction in 1991 it was described as: “After Thorvaldsen: An Italian White Marble figure of Venus, mid-19th Century…” and it was valued at the modest price of £1500-£2000.

So within 57 years the sculpture had been reduced to being “After Thorvaldsen”, and the firm’s previous knowledge of its good provenance had been lost.

A technical and stylistic evaluation, however, shows that the statue is of an unusually high sculptural quality right down to the least detail. As a whole, it appears different from other versions of Venus in the smaller format. One special characteristic is the long, supple neck, giving the little head an extra strong twist to the right. This and details such as the shape and size of the mouth seem to relate to the statue of Psyche and the Unguent of Beauty from 1806, i.e. from the time when the first small Venus was also created.

So there is a great deal to suggest that Thorvaldsen and his assistants sculpted the marble figure after the first original small model of Venus from 1804.

There are still unexplained details about the Nevinson and Marten families, and there is still the question of what was meant by “Copenhagen Museum”. Could it be the old Royal Collection of Fine Art, or was it in reality Thorvaldsens Museum which was then about to be created – and where the statue has thus, by a long and meandering path, finally ended?

Eva Henschen

Fig. 111. Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844): Venus with the Apple, modelled 1804. Marble. H: 90.6 cm. Inv. no. A916.

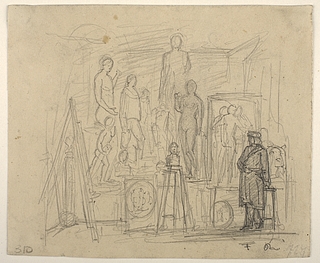

Joachim Ferdinand Richardt (1819-1895): Thorvaldsen in his Studio at Charlottenborg, 1840-1842 Thorvaldsen Sketching, 1840-1842

Pencil on paper. 120×145 mm.

Pencil on paper. 105×112 mm.

In 1840, the then 21-year-old Academy pupil Joachim Ferdinand Richardt painted a picture of Bertil Thorvaldsen in his studio at Charlottenborg. The painting, Thorvaldsen in his Studio at Charlottenborg, was later acquired by Thorvaldsen himself for his collection of paintings. In addition, Richardt also produced several drawings of the ageing sculptor surrounded by his works, including two which were presented to the museum in 1996 by descendants of J. F. Richardt in the USA.

In the drawing Thorvaldsens Studio at Charlottenborg, Thorvaldsen is looking towards his sculptures, which are crowded together in apparently random order. Venus with the Apple, The Three Graces and A Recumbent Lion are the only ones of Thorvaldsen’s works that can immediately be identified. On the back of the drawing can be seen the outline of a figure, which must also be assumed to be Thorvaldsen, standing by a modelling stand and dressed in a loose garment. Behind the figure it is possible to discern a horse’s tail and A Recumbent Lion on a high plinth. On the other drawing, Thorvaldsen Sketching, Richardt has portrayed the sculptor sitting on a stool with a drawing board and a pen in his hand. In addition, there is a study of Thorvaldsen’s hat and two of his hand, holding a scroll.

The newly acquired sketches have not been used as a direct model for the painting, but are studies done to capture the atmosphere in the studio. Thorvaldsen’s biographer J. M. Thiele provides the following description of Thorvaldsen’s apartment and studio in Charlottenborg: “In Charlottenborg, Thorvaldsen lived on the ground floor apartment looking out towards the botanical gardens, which since the founding of the Academy had been at the disposal of the Professor of Sculpture. It had awaited him since 1805 without being used by him for more than the one year 1819-20, when he was last in Copenhagen. These rooms had now been extended with the addition of spacious studios in which some of the works sent back had been arranged temporarily”. (J. M. Thiele, Thorvaldsen i Kiøbenhavn, 1856, p. 57).

J. F. Richardt’s career was different from that of the other painters of the Danish Golden Age in that in 1873, at the age of 54, he emigrated to the USA. He settled near Niagara Falls, but later moved to San Francisco and then to Oakland, California, in 1877.

Gertrud With

Fig. 112. Joachim Ferdinand Richardt (1819-1895): Thorvaldsen in his Studio at Charlottenborg, 1840-1842. Pencil on paper. 120×145 mm. Thorvaldsens Museum. Inv. no. D1872.

Fig. 113. Joachim Ferdinand Richardt (1819-1895): Thorvaldsen Sketching, 1840-1842. Pencil on paper. 105×112 mm. Thorvaldsens Museum. Inv. no. D1873.

Bertel Thorvaldsen: Tomb of the children of Helena Poninska,1835

H: 156,2 cm. W: 241,5 cm. Inv. no. A917. Plaster cast

Thorvaldsen’s sepulchral monument to the Polish Princess Helena Poninska’s two children, Wladyslaw and Helena, who died about 1833 at the ages of 21 and 19, stands today in the State Museum in Lwow, but Thorvaldsens Museum acquired a plaster cast of it in 1995. This saw the completion of the sequence of preparatory sketches and models for this work, which had already formed part of the museum’s collections.

It was during the Princess’ visit to Rome in 1834-35 that Thorvaldsen undertook to execute the relief. The original intention of the Princess, who during her stay in Rome was in contact with several of the artists living there, was that the relief should be erected in Kraków Cathedral, but when Thorvaldsen had finished work on it, it was instead placed in the chapel of the castle belonging to the Poninski family in Czerwonogród in present-day western Ukraine.

A contract for the relief was drawn up between the Princess and Thorvaldsen in April 1835. Its wording made clear that the relief was to represent “the transition from this to the other world”, picturing the two dead children on their journey from the world of the living to the realm of the dead. In addition the contract established that the representations of the two young people should be portrait likenesses and that the figures were to be almost life size. The requirements of the contract, however, were in no way the only wishes of the purchaser that Thorvaldsen had to accommodate. Thus the archives of Thorvaldsens Museum contain two undated letters from Princess Poninska to Thorvaldsen concerning the work, and these lead to the suspicion that the sculptor had relatively little to say in its general conception. For the two letters contain detailed instructions for the elaboration of the relief’s motif, while in the second of the two written instructions the Princess even takes the liberty of asking the artist to make changes to some of the features with which she had otherwise asked him to provide the work in her first letter. She has clearly felt compelled to excuse her interference in the sculptor’s work and in connection with the last set of instructions comments that “I, too, am a painter”, thereby seeking to justify her considerable share in the process of artistic design.

Poninska’s letters to Thorvaldsen make possible a precise interpretation of the motif in the monument. The transition from one world to the other is clearly represented in a perfectly literal sense, in that the two worlds are represented by segments of spheres at the bottom of the relief, while the two young people are floating from one sphere (the world) to the other. The figure on the left of the relief is the genius of death, conducting the son Wladyslaw towards the land of the dead, and at the extreme right Princess Poninska can be seen, to her obvious despair being left in the realm of the living. The arched shape of the relief is presumably to be seen as a symbol of the heavens, because in one of her letters to Thorvaldsen, the Princess writes that it should be possible to see the “firmament” above the figures.

There are today several damaged sections in the marble relief in the State Museum in Lwow, and these are naturally also visible in this cast first exhibited in the Museum of the Royal Castle in Warsaw on the occasion of the exhibition “Thorvaldsen in Poland” in the winter of 1994-95. The cast was the subject of a small exhibition in Thorvaldsens Museum in the autumn of 1995.

Thomas Lederballe

Fig. 114. Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844): Tomb of the children of Helena Poninska, 1835. 156,2×241,5 cm. Plaster cast. Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen. Inv. no. A917.

Puk Lippmann: Rug

270×270 cm. Panama/linen weave in Finnish paper yarn on natural died flax cord. Natural colours – ochre, red, blue, green, bleached white and blue-black. Gift from the Ny Carlsberg Foundation.

Between 9 September and 8 October 1995, the weawer Puk Lippmann (b. 1945) exhibited five large rugs in the entrance hall to Thorvaldsens Museum. These rugs had taken their inspiration both for colour and pattern from the floors in the museum – not in the sense that they were directly wowen copies of the floors – but they had all absorbed dense colours of the museum and had been made to the same units of measurement as the mosaic floors.

Rug number two in the exhibition was that closest in spirit to M. G. Bindesboll and was the one the museum was most interested in acquiring. However, as the School of Architecture in the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts was about to be established in new premises in the old Royal Dockyard (Holmen), that very rug was needed there – a kind of modern bridgebuilding between past and present.

However, the Ny Carlsberg Foundation agreed to make funds available for making the rug desired by Thorvaldsens Museum, and so Puk Lippmann and her weavers set about making a new rug. It is very similar to the one in the Academy of Fine Arts, almost its twin, but like everything made by Puk Lippmann it is nevertheless a creation in its own right, with new colour combinations, different borders and an aura all of its own, which it radiates from the floor of “Thorvaldsen’s Room” on the first floor of the museum.

Eva Henschen

Fig. 115. Puk Lipmann (b. 1945): Rug, 1994-1995. 270×270 cm. Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen.

Last updated 11.05.2017