Grundtvig and Copenhagen During Denmark's Golden Age

- Flemming Lundgreen-Nielsen, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 1997

This is a re-publication of the article: Flemming Lundgreen-Nielsen: ‘Grundtvig and Copenhagen During Denmark’s Golden Age’, in: Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum (Communications from the Thorvaldsens Museum) p. 1997, p. 73-95.

For a presentation of the article in its original appearance, please see this facsimile scan.

Did Grundtvig really belong in Copenhagen during the Golden Age? In a literal sense, of course yes. He lived in the capital throughout his professionally active life, spending a total of 65 years at 24 different addresses. But in a figurative sense, virtually no. He differs in important respects from the other great personalities of the age.

Fig. 56. Henrik Gottfred Beenfeldt (1767-1829): The Gardens of Rosenborg Palace. 1810. Tempera. 240 X 332 mm. Københavns Bymuseum, Copenhagen. lnv. no. 1932. 143. Rosenborg Gardens were opened to the public in 1771, offering the pleasant possibility of taking a country walk within the ramparts of the confined and overcrowded capital. Here, nurses tending small children had a chance of meeting soldiers from the barracks of the Royal Guards close to Rosenborg Palace, and even outside the summer season people such as Grundtvig and later the young Georg Brandes could find a place of solitude for quiet reflection.

Søren Kierkegaard was able to play upon the city’s possibilities like a virtuoso on his instrument, transforming streets, squares, cafes, the theatre and the churches into catalysts for the tireless process of selfanalysis and self-projection that formed the basis of his authorship. Hans Christian Andersen did the same, though to a less deliberate extent. But this was not how Grundtvig used Copenhagen. When Grundtvig walked in the streets of the capital it was not just to be seen but because he had to go somewhere, for example to a meeting in the Rigsdag (Parliament), or to call on friends. Sometimes – though perhaps not so very often – he sought solitude, inspiration or a little fresh air by walking in Rosenborg Park (fig. 56) or on the city ramparts at Vesterport. He made one brief and heartless reference to the amusement park in Tivoli Gardens (which had opened in 1843) dismissing it as “a fleeting whim of fashion” – one of his prophecies that was wide of the mark! However, he certainly went there four times between 1856 and 1860 – not to ride on the switchback, but to make speeches to students and about the Constitution.

At this time the loyal citizens of Copenhagen had four fixed points on which to take their bearings: the University, Frue Kirke (the Church of Our Lady), both in Frue Plads (Our Lady’s Square), the Royal Theatre in Kongens Nytorv (the King’s New Square) and lastly the King and the Court, who had taken up residence in the Amalienborg mansions after the destruction of Christiansborg Palace by fire in 1794. Grundtvig did not have a cordial relationship with any of these points on the map of Copenhagen, nor did he wish to.

The University had pronounced him unqualified for a professorship in history and mythology, not just once but twice (in 1816 and again in 1817) after which he gave up applying. As a chaplain at Vartov Hospital ( an institution for the old and infirm) from 1839 onwards it was his duty to supervise university examinations in theology, but as a rule he failed to turn up, omitted to send an excuse and in this way wreaked havoc in the examination system, with the result that after a complaint case in 1849 he was officially relieved of his duties. He did, however, act as an examiner of probationary sermons right up to 1855. His youthful plans of writing a doctoral dissertation (in Latin, of course) never materialized.

During the Reformation festivities in the jubilee year of 1836, a fortnight after the inauguration of the new university building in Frue Plads, doctorates were granted to 33 persons, but Grundtvig was not one of them. He himself admitted that his performance on the same occasion as unofficial opponent to a doctoral candidate (who had called the supranaturalism of the period unreasonably simple-minded) had been less than successful because he no longer mastered Latin well enough to be able to hold his own in an oral discussion – the confounded mumbo-jumbo weighed him down and had a paralysing effect. On the other hand he marked the jubilee – or at all events his publishers did – by issuing the first instalment of his Sang-Værk (Collection of Hymns), whose Danish title was the name also used by Copenhageners for the carillon ( destroyed during the bombardment of 1807) in the University’s neighbouring building, Frue Kirke.

For the rest of his life Grundtvig regarded the University of Copenhagen as a ‘black school’, a phrase used at the time to denote a barren, or dead seat of learning, and he mocked it repeatedly on account of what he regarded as its Byzantine, boyish scholasticism, elite Latin culture and unnecessarily complicated examination system. He was not a member of the scholarly associations based on secret election, such as Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab (The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters) and Det Kongelige Danske Selskab for Fædrelandets Historie (The Royal Danish Society for the History of the Fatherland) but in 1839 he joined the newly formed, more liberally organized Dansk historisk Forening (Danish Historical Association). At the same time he himself founded a Copenhagen debating society, the Danske Samfund (Danish Society), along very different and democratic principles, although during these last years of Frederik VI’s life he still regarded democracy as an unnecessary import from France and for the most part maintained a satirically scornful attitude towards it.

It is unlikely that Grundtvig frequented Frue Kirke after its reconstruction in 1811-29, for he had his own churches, as a guest preacher in general and also as an appointed clergyman at Vor Frelsers Kirke (Church of Our Saviour) and – for the most protracted period – at the church attached to the Vartov Foundation. Moreover, after the affair of the publication of his probationary sermon in 1810-11, he was at loggerheads with the majority of Copenhagen’s clergymen and theologians. The estrangement between himself and his highly cultured and esteemed distant relative Bishop J. P. Mynster, for example, was permanent. The post Grundtvig was finally given after applying at the age of 56 was not one that lent prestige in the capital. Right up to his burial in 1872, educated people could still be heard referring to him as “that clergyman for the old women at Vartov”.

Grundtvig probably never visited the Royal Theatre after the occasion in January 1809 when he was the chief instigator behind the booing of L. C. Sander’s history play about Knud Lavard – not so much because of any indignation at the play itself as at Sander’s unfounded yet self-assured criticism of Adam Oehlenschlager, the Danish poet much admired by young people at the time. In a famous – and notorious – conversation that took place at some time between 1857 and 1863, Grundtvig is said to have discussed the theatre with no less an authority than Romanticism’s leading Danish actress, Johanne Luise Heiberg, at the home of the prime minister, C. C. Hall. Already during dinner Madame Heiberg was disturbed by Grundtvig’s forthright statements about all manner of things. Afterwards their officious hostess had shown them into a small room and placed them together on a sofa with the aim of creating a ‘historic situation’. It was unfortunate. Grundtvig admittedly acknowledged an actor’s first performance of a role with an “All right, I’ll let that pass”, but insisted that the second and subsequent performances amounted to pure affectation. Madame Heiberg declared that the same applied to a clergyman who preached the same sermon in two different churches. Grundtvig replied that that was a very different matter, because the preacher used his own words. Madame Heiberg concluded that Grundtvig did not want to understand that a good actor identifies himself with the dramatist.

Fig. 58. Jørgen Sonne (1801-1890): Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig in the Poets’ Boat. 1847 (reconstructed in the 1950s). Part of the frieze round Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen. Grundtvig spent most of his life in his study, reading, thinking, writing and smoking his pipe, all of which is said to have given him a permanently pale complexion. He seldom ventured far afield, but on Thorvaldsen’s return to Copenhagen, he joined the poets in a boat to greet the famous sculptor along with the rest of the citizens of Copenhagen.

The dissonance which existed between Grundtvig and the theatre and acting emerges very clearly in his treatment of the subject in his writings on the history of the world, although curiously enough, in May 1841, he was seriously tempted to go to the Royal Theatre to see Sille Beyer’s saga drama Ingolf and Valgerd. At this time Grundtvig was absorbed in his campaign to establish a Danish Folk High School and had drawn attention in several pamphlets to Iceland during the Middle Ages, when stories were told in the mother tongue about anything and everything in the form of sagas. He believed it was a unique example in European history of an entire country more or less functioning as a university in the national language. This is why he was most interested in seeing the scenery: the interior of an Icelandic house. But nothing came of it.

Nevertheless, the fact that the notion occurred to him at all may also demonstrate that the Royal Theatre, with its costumes, scenery and backcloths, provided audiences with historical and geographical enlightenment at a time When the practice of opening museums to the public had only recently been initiated and few people were in a position to go travelling abroad. Grundtvig’s relations with the monarchs of his time were good: professional with Frederik VI, but more cordial with Christian VIII, whose queen, Caroline Amalie, must be reckoned among the first real Grundtvigians. Already as crown princess she had summoned Grundtvig in 1839 to give private lectures on history at Amalienborg Palace for the benefit of herself and her ladies-in-waiting, a regular practice until Grundtvig’s fit of madness in March 1844, after which it was discontinued. He never cultivated the court and its circles as an institution. He did participate, however, in the Reformation festivities in Copenhagen in 1836. Afterwards he wrote to Ingemann:

For the first time, and probably also for the last, I sat recently with so many, indeed with all the others, chewing and drinking heavily in the King’s antechamber, where I doubtless found it less tedious than normally, especially as one received money for it into the bargain [a commemorative medal] , yet I had to leave the table hungry while observing my neighbours smacking their lips, partly with oysters, in which I was not interested, and partly with other rarities which no-one offered me and I could not be bothered to exert myself to reach.

The tone of the letter is revealing: court life held no interest for him whatsoever, and the same applied to the good things of life, such as luxury foods. On the occasion of Christian VIII’s silver wedding on 22 May 1840 Grundtvig was made a knight of the Dannebrog – which in view of his wide reputation as a know-all who regularly contradicted everyone else was regarded by some students in the new liberal reading society, Academicum, as both comical and alarming. It was to be his only decoration. Grundtvig’s presence at Christian VIII’s anointment on Sunday, 28 June 1840, in the Chapel of Frederiksborg Castle, apparent from J. v. Gertner’s drawing from 1846, is a fabrication (fig. 57). The artist wished to include the most famous personages of the period amongst the spectators, and Grundtvig agreed to sit for Gertner post festum in the artist’s studio in Christiansborg Palace. Grundtvig was not actually in Hillerød on the day of the anointment: he was preaching at Vartov and in the evening arranged a friendly get-together in the Danske Samfund outside the normal season for the society’s meetings. In both cases he brought along a leaflet with some of his recent poems: on the first occasion two hymns and on the second three toasting songs (to the king, the queen and Ogier the Dane).

Compared with other intellectual personages of the day, Grundtvig was a stay-at-home. The grand tours through Germany, France, Austria and Italy financed by the royal purse for so many applicants had no appeal to him. On the basis of his knowledge of the history of the world and of the Church he was sceptical towards Germany, which he regarded as persistently troubled and fermenting, and he preferred to disassociate himself from the Catholic south of Europe, which he regarded as degenerate. Characteristically, his four visits to England – in the summers of 1829, 1830, 1831 and 1843 – were made specifically for the purposes of research and in order to visit libraries. Grundtvig’s only holiday (a concept unknown in the labour market of the times!) was a fortnight spent in Norway in the summer of 1851 – a veritable triumphal skaldic progress. He retained a life-long coolness towards Sweden; despite earnest requests in his later years he never even crossed the Sound, nor did he ever visit the first Folk High School, founded at Rødding in North Slesvig, though he had of course frequently been invited to do so. Grundtvig’s travels took place in his smoke-filled study through his reading, and he paid more attention to phases in time than stations in space. He adopted what he called – in another context – “a hawk’s-eye view” of the world around him.

As an elderly man, Grundtvig himself became to an increasing extent one of the sights of Copenhagen. He won wide acclamation for the first time from two successive younger generations with his Mands Minde (Living Memory) lectures on the previous 50 years of European history, given at Borch College in Store Kannikestræde (Great Canon Street) in the autumn of 1838. As far as popularity was concerned, this was the turning-point in his life. He became a central figure in the city scene. When Thorvaldsen returned to Denmark on 17 September 1838 Grundtvig sat (as can be seen on the frieze by Jørgen Sonne that decorates the outside of the walls of the Thorvaldsen Museum) in a boat together with other writers:

Oehlenschläger, Heiberg, Hertz, Winther and Hans Christian Andersen (fig. 58). The succession in December 1839 also brought about a change in public attitudes and values, and Grundtvig was to benefit in unpredictable ways as a newly established popular orator and politician (a matter that deserved closer examination). Whereas formerly he had been regarded as a frightening – albeit fascinating – eccentric, he was now recognized for his qualities. At the queen’s request he thus acted as interpreter when Elisabeth Fry, the British prison reformer and Quaker, visited Copenhagen’s prisons in August 1841. In September that same year the queen also appointed him as director (for life) of her new orphanage in Nørregade (today the address of the present Folketeater), which was moreover, as from 1842, exempted by special decree from supervision by the Copenhagen School Board. In addition to his popular activities in the Danske Samfund he received and accepted invitations to speak in connection with discussions on Scandinavian, national-liberal and national affairs. At a celebration at Skydebanen (the Shooting Range, a Copenhagen clubhouse) on 14 November 1849, Oehlenschlager’s 70th birthday, Grundtvig presented a song and made three speeches, and it was also he who, when requested to do so by the arrangers, crowned the old poet with a laurel wreath on behalf of the women of Denmark. Even those who felt offended by Grundtvig’s manners and opinions were overwhelmed by his charisma. This is evidenced by a profile of him in the satirical magazine Corsaren (The Corsair) on 9 September 1853 (fig. 59). Ist author, Claudius Rosenhoff, admittedly suggests at first that Grundtvig should be locked up in Bistrup (a lunatic asylum near Roskilde) but concluded by regretting his evaluation:

“when I saw him tiptoe forward on a festive occasion, crown Oehlenschläger with a laurel wreath, kiss him and proceed to declare his maxims, then it seemed to me that we were more or less clever pygmies compared with this half-crazy giant.

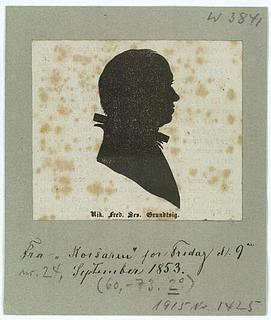

Fig. 59. Claudius Rosenhoff (1804-1869): Profile of Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig. From the satirical magazine Corsaren. 71×42 mm. The Royal Library, Copenhagen. Grundtvig was a poet, philologist, historian and educationist as well as clergyman, but in the popular imagination he was primarily thought of as a person attired in a Danish Protestant cleric’s ruff and gown. He is immediately recognizable even in this silhouette from Corsaren on the occasion of his 70th birthday in 1853.

The 50th anniversary of Grundtvig’s ordination was celebrated in 1861 by a special service at Vartov, and later that day D. G. Monrad, minister for Ecclesiastical Affairs and Public Instruction, gave him a rank on a level with the Bishop of Zealand ( and, contrary to the wording of the royal commission, also the title of bishop) . During the last nine years of Grundtvig’s life his supporters arranged so-called Friends’ Meetings, which were held during the days around his birthday, 8 September. His Vartov congregation and its loud, staccato hymn-singing at a particularly fast tempo (known as “Vartov gallopades”), was also brought to the attention o f tourists. The young English poet Edmund Gosse has related that in the summer of 1872, a few months before Grundtvig’s death, he was recommended to attend a service at Vartov. He received an unforgettable, though no doubt somewhat exaggerated impression of Grundtvig as an ancient heathen sacrificial priest with a sonorous, ghostly voice .

Grundtvig and the Golden Age

Grundtvig’s relationship with most of what is celebrated nowadays as Copenhagen’s Golden Age was not particularly cordial. In 1838 he said bluntly: “My writings as well as my speeches prove that few can be more critical than I of present conditions in Denmark and elsewhere.”

In general, the artistic manifestations of the Golden Age left him cold. His lack of interest in the theatre has already been mentioned. He was devoid of musicality and never attended concerts, one of the period’s favourite forms of public performance. But of course people sang in his churches. It was moreover in his auditorium at Borch College on 17 October 1838 that a crowd of supporters burst out singing his national ballad about the naval hero Peter Willemoes “Kommer hid, I Piger smaae” (Come hither, you little girls) in unison. Thus was founded the specifically Danish tradition of singing a song before and after a public lecture. But even though the finest composers of the Golden Age, such as Weyse, Berggreen, Hartmann, Rung and Niels W. Gade, set Grundtvig’s words to music, no evidence has come to light of any contact between them and him.

Sculpture and painting were regarded by Grundtvig as the lowest and most materialistic art forms on a scale headed by “the art of the word”, or poetry. Behind this evaluation lay undoubtedly the Old Testament’s commandment against making images of God. In his poem “Kiærminde-Bladet” (The Forget-me-not Leaf ) written as a farewell greeting to the poet B. S. Ingemann in April 1818 on his departure for a two-year tour of the south of Europe (printed in October that same year) Grundtvig earnestly warned his slightly younger friend against Rome’s refined art, heathen as well as Catholic (stanza 64): “No Christ with colours can be painted / Nor carving made of Him in stone”. In stanza 66 he acknowledges deviating in this way from the outlook on art held by the academic world, according to which those who have no appreciation of music, painting and statues are to be reckoned as barbarians and pious blockheads. Stanza 68, the last in the poem, represents a harsh clash with both Classicism and Neo-classicism, because precisely when the art praised in refined circles appeared to be most spiritual it was “painted, ugly idolatry”; in Grundtvig’s view, Classicism consisted in permitting the lust of the flesh to turn Itself into a religion under the pretext of being true spirituality.

Nevertheless, Grundtvig developed what amounted almost to a love for the great Danish sculptor Thorvaldsen, who was famed throughout Europe, due to the fact that the latter had contributed, as a human being and historical figure, to a new and significant breakthrough around the turn of the century. It was certainly not on account of his “Pictures in ecclesiastical taste” – as Grundtvig, in a memonal poem at Thorvaldsen’s death in 1844 (printed belatedly in conjunction with the opening of the museum in 1848) coldly called Thorvaldsen’s Christian statues.

At the inauguration of Thorvaldsen’s studio at Nysø in 1839 Grundtvig had already stated bluntly in print in the magazine Brage og Idun (Brage and Idun) that he had never admired any of the master’s works, for he regarded God as the only competent sculptor. In his Haandbog i Verdens-Historien (Handbook of World History), I, 1833, Grundtvig expressed his preference for that part of the history of ancient Greece when the written and spoken word and spirituality dominated, as in Homer, the historian Herodot, the tragedian Aeschylus, the philosopher Plato and the orator Demosthenes. In his view, the circumstance that the Greeks, through the Olympic Games, gradually attributed greater importance to the hum an body and physical activities than to artistic disciplines was already a sign of decline, and matters deteriorated even more seriously when the Classical art of sculpture started producing petrified versions of these athletes. This evaluation on Grundtvig’s part was to affect the later Folk High Schools’ attitude to the matter.

He expressed his views on painting even more sparingly – on Danish national painting probably not at all. Even though Grundtvig, through his personality, attracted the best of the Golden Age’s young painters and draughtsmen – P. C. Skovgaard, Christen Købke and J. Th. Lundbye – he was probably never interested in their landscapes, though he did actually prompt one of them: Vilhelm Kyhn’s neat, somewhat impersonal painting of Udby Church was commissioned by Danish women as a gift on Grundtvig’s 70th birthday in 1853 (fig. 61), but it is by no means among the classics of the Golden Age. Twice in his life Grundtvig let himself be painted by two artists at once in order to save time sitting as a model: in 1847-48 by P. C. Skovgaard and Constantin Hansen, then in 1862 by Constantin Hansen and Wilhelm Marstrand (fig. 62). It made matters unpleasant for the artists, who had to keep side-stepping round each other to portray him, and furthermore, at least in 1862, had to submit to being entertained by his low opinions – in principle – of their art. Grundtvig’s warmest appreciation was of course reserved for the writers of the period. His beloved king, Frederik VI, although lacking the ability to understand the fine arts, nevertheless supported throughout his life such writers as could be trained to benefit and please the fatherland.

The great breakthrough at the turn of the century – the stroke of lightning that flashed from Grundtvig’s older cousin, the philosopher Henrik Steffens, and the latter’s eager pupil, the newly aroused Romantic poet Adam Oehlenschlager, which virtually represented a follow-up in intellectual life to the patriotic revival sparked off by the thundering guns of the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801 – was a fixed starting-point throughout Grundtvig’s life for his hopes for the development of the nineteenth century. However, the moment he saw the individual works his criticism was harsh. He regarded Oehlenschläger’s writings after Nordiske Digte (Nordic Poems) , 1807, as a decline into materialism and sensuality – later, in 1818, he declared him to be “a masterful flesh sculptor, the artist idolized by all youth: an idol-maker”, which was a harsh way of putting things, especially coming from Grundtvig.

Even Grundtvig’s loyal friend Ingemann, who was a senior master at the academy (a branch university) in the small but venerable historic town of Sorø had to make do with temperate praise – Grundtvig did not care for Ingemann’s famous historical novels, which were bestsellers in their day, because he found the novel, as a literary genre, worthless. He regarded Ingemann’s hymns as blessed little cherubs, not grownup saints, and passed over his morning songs for children in a letter with a brief note of acknowledgement.

Most frequently mentioned by Grundtvig are two of his friend’s youthful publications, which nobody reads any more: the epic poem De sorte Riddere (The Black Knights ), 1814, and the closet drama Reinald Underbarnet (Reinald the Miracle Child), 1816. He took genuine pleasure in Ingemann’s cycle of poems Holger Danske (Ogier the Dane), 1837, because it gave an adequate impression of the passage of the Danish national character through heathen well as Christian times. The others, whom we now regard as the great writers of the Danish Golden Age, such as Steen Steensen Blicher, Heiberg, Hertz, Hans Christian Andersen, M. Goldschmidt, Kierkegaard and Frederik Paludan-Müller, are touched on by Grundtvig in the form of references to titles, but without revealing any real standpoint or assessment.

It was thus not Grundtvig’s opinion that the first half of the nineteenth century represented a cultural Golden Age at all. On the contrary, he complained time and again, from the bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807 onwards, about the apathy and somnolence of the period, its cultivation of the material and the comfortable, its inane masquerades and illuminations, its oyster and turtle parties, in short, its serving of “tasty pork sausages” as he bluntly expressed it? At the beginning of the 1820s he wrote to Steffens about his own times, asserting that they represented a deathly quiet graveyard where some people collect worms, others dig vainly for treasures and yet others put all sorts of things together to form monstrous skeletons. At the time, the period itself was referred to as a ‘golden age’ only on a few occasions – the term was not to be widely used until after the 1890s. In 1894 the leading Danish critic of modern literature, Georg Brandes, was still grumbling in a literary review:

Vilhelm Andersen likes to use the tedious, insipid term ‘golden age’ about the period in literature when Poul Møller lived. Not all that glittered in it was gold, and it was certainly no gold mine. Grundtvig was actually one of those who used the term most frequently – first as historian and afterwards as Christian preacher and public educator. When and why did Grundtvig change his mind about his own times?

Grundtvig’s View of the Golden Age

In Grundtvig’s view, the epoch-making New Year’s Day heralding the nineteenth century consisted of the contributions made by Steffens, Oehlenschläger and Thorvaldsen.

Steffens (see fig. 1, p. 9), in his seventh introductory lecture, described the great past when the gods walked on earth and when words and actions were one and the same thing. He concluded his historical survey in his eight lecture by prophesying a second coming of the more splendid age with reference to German Romanticism and Goethe. The romantic poem with which Oehlenschläger made his debut, “Guldhornene” (The Golden Horns), 1802, made reference in the same style to precisely the time “when Heaven was on Earth”, the the point being that the golden horns were doomed to be lost, because the present day only saw their value as metal, not their poetic and intellectual message about the divine. The golden horns may have vanished, but on the other hand Oehlenschläger’s poem about them became, in a figurative sense, a third golden horn, an inspiration for poetry and intellectual life for the rest of the century, at all events up to and including Vilhelm Andersen’s doctoral dissertation on the subject in 1896. At the same time Thorvaldsen’s statue of “Jason with the Golden Fleece” in Rome represented a rebirth of Greek antiquity (fig. 63).

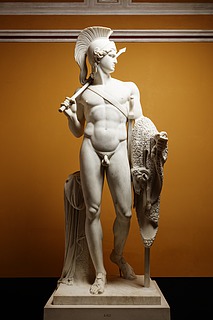

Fig. 63. Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844): Jason with the Golden Fleece, 1803-1828. H: 242 cm. Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen. A822. Grundtvig regarded sculpture as the petrifaction of the lust of the flesh and detested Neoclassicism as a carefully polished monument to human imperfection. He accepted Thorvaldsen’s Jason only as one of several symbols of the spiritual awakening of the Danes at the beginning of the 19th century.

This new generation therefore not only had a past golden age to yearn for. Included in its outlook was the prospect of a new golden age that possibly lay ahead. The model was moreover Christian: from Paradise through the Fall of Man to the new Jerusalem. In spite of everything it kindled optimism and the energy for new achievements.

Older humanists, like Professor Knud Lyne Rahbek in his rural home outside Copenhagen near Frederiksberg Palace, had a different outlook. Rahbek always felt that Denmark’s Golden Age lay irrevocably behind in the eighteenth century, in the Holberg era up to about 1750, in Ewald’s and Wessel’s period during the 1770s and the prosperous decade prior to the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801. At the 20th jubilee of the Norske Selskab (the NorwegIan Society) in 1792, Rahbek spoke specifically about the splendid days of yore, conscious of the fact that the jubilee was more of a loving farewell to the past than a joyful welcome to what lay ahead. For the mature Rahbek Denmark’s truly Golden Age was the period 1784-99, when public opinion coincided with public spirit – when the whole population was concerned with renewal and reform.

This idea of a golden age as held by Rahbek is described very differently by Grundtvig in his Verdenskrønike (World Chronicle), 1812: Suhm’s best historical work, Historien af Danmark, Norge og Holsten udi tvende Udtog (The History of Denmark, Norway and Holstein in Two Extracts), 1776, was changed in later editions (1781 and 1802) in order to “make young people believe that our age is the golden instead of the poisonous”, and the general outlook was thoroughly materialistic:

…great wealth had flowed into individual homes, sumptuousness and voluptuousness grew on the gold-midden, selfishness thrived. People completely forgot that it is God who gives them their daily bread and thought only of reaping and

enjoyment.

The tightening up of the Printing Act in 1799 had unfortunately silenced the “intellectual stock exchange”, but it also prevented “ungodliness, defamation of character and rebellious talk. Everything seemed about to fall into a sleep of intoxication or stupor” – until God’s voice of thunder spoke through the guns in 1801 and aroused the nation. Rahbek’s academic respect for the culture of the Classical Roman Empire was certainly not shared by Grundtvig either. Writers in those days, he wrote in Verdenskrøniken, 1812, were often “despisers of God, immersed themselves in life on earth and abused their art to gild vice, or to win the favour of the powerful by flattery”. In Grundtvig’s view, the empire of Augustus stood as a large, dead tree, its branches withered, with the result that his rule was only “Rome’s golden era, just as the glow of the evening sun sometimes seems to us to gild with a more delicious lustre than the blush of dawn” – but it was followed by night, not by day, and its flowers produced seeds that could not germinate. Grundtvig warned against the attempts made by the eighteenth century’s schoolmasters (it could be Rousseau and Pestalozzi) as well as Napoleon’s empire, each in their own way, to revive these so-called golden days. In his _Haandbog i Verdens-Historien, I, 1833, he declared that we must on no account confuse “the golden age and golden mean of ‘tyranny’ with that of the human. Spirit”.

Grundtvig found a more positive notion of the golden age in Nordic heathendom and also in Christendom. In a little paper entitled “On Norse mythology”, 1807, he examines the main course of events in Nordic mythology, especially with the help of the poem in the Elder Edda called the Voluspa. Here he refuted the idea that the creative activities of the Aesir on the “Ida Plain” represented a ‘golden period’. The delight of the gods was a disappointing illusion in a vain dream of freedom – for they themselves had thrown away the golden tablets of wisdom and would not find them again until after Ragnarok, the end of the world.

In the academic dissertation of his youth “Om Religion og Liturgie” (On Religion and Liturgy) written in that same year he emphasized that the Greeks, the Jews and the Norsemen all had a history that faded away in “a golden age when the gods walked about on earth, and the celestial and the terrestrial merged in a single idea”. He failed to see the interesting point about a common notion of this kind in the epic reflection of this golden age or in recent philosophy’s eternal idea. The important thing, he felt, was its reality as imposed by conditions of the period, that is in history, most clearly discernible in the Bible’s accounts of Paradise and the Fall of Man. The golden age was tantamount to innocence, which in turn permitted an unimpeded confluence with the celestial. The Fall was the loss of innocence, expressed through knowledge, which gave life an intrinsic value and man living conditions of his own choice. And for this reason, death was set “as a cherub with a shining sword between the everlasting and the finite”. These two worlds could be reconciled only through Christ’s death. In a similar fashion, the 1812 chronicle concluded that a phoenix rising from its own ashes might cause the people to be reborn to new spirituality, “and the name of this wondrous bird is Christendom”.

This view reappeared in Grundtvig’s schoolbook Græsk og Nordisk Mythologi for Ungdommen (Greek and Nordic Mythology for Young People), 1847, although this time incorporating the national aspect. Through the resurrection of Balder, the golden age lost by the Aesir on the Ida Plain was to be replaced by a ‘golden year’ (fig. 64). Grundtvig explained this to school pupils as a renewed form of modern Christianity in which each nation and people would arise in a clarified, that is to say purified, reinforced and transilluminated form in order to become part of ordinary human life. The order was: first a member of a nation, then a human being, and thereafter a Christian.

Grundtvig’s Golden Year

In his younger days, Grundtvig’s most frequent starting point was that the everlasting and the finite were diametrical opposites. From around 1815 he began to modify this outlook, and ten years later it emerged as a conviction that for those who believe, a “golden” year can be here and now in this world. Throughout the rest of his life he used the phrases “golden age” and “golden year” quite consistently: “golden age” designated the vanished part and “golden year” the near future or even the present. The actual term “golden year” is derived from the Jewish year of jubilee, which occurred every fifty years (Leviticus 25). The term appeared in Danish as a reproduction of Joshua 6:4. in the oldest Danish translation of the Bible, from the second half of the fifteenth century: a “forladælses ællær gledins ællær gyllins aar” (a year of forgiveness or joy or gold). It had just been published 1828 after a manuscript. In the second, expanded edition of Krønike-Riim til Levende Skolebrug (Chronicle Rhymes for Practical Use in Schools), 1842, Grundtvig drew attention to this Dano-Iexical meaning in a newly appended note to his poem “Jerusalem”, the last in the book: “The Golden Year is the Danish expression for “Jubilee year”.

The biblical concept of a golden year occurring in the middle and at the end of a century is explained by Grundtvig in his Haandbog i Verdens-Historien, I, 1833, with references to the Pentateuch an ancient Jewish historian Josephus, as being the result of a kind of social distribution policy: all domestic debt was remitted, and inherited land that had passed out of a family was restored to it. Grundtvig believed that the main purpose of the ‘golden year institution from the point of view of the citizenry .was to safeguard private property and prevent the dominance of the big landowners. Combined with the law about a year of rest every seventh year, when all Hebrew thralls were set free, It ensured that the Jews would live in “a country where no doubt, as everywhere, only few became very rich an even fewer were very poor”. The weighty volume concludes with Christ proclaiming (according to Luke 4:19, a quotation from Isaiah 61:2) “the new era as a golden year for the whole of mankind”.

The term “golden year” was undoubtedly used many times in Grundtvig’s sermons and theological writings, but a comprehensive investigation has not been made. The Sang-Værk has 40 instances of the use of the term in his hymns. It is used in “Vidunderligst af Alt paa Jord” (Most wonderful of all on earth) about life after death, “Evighedens Gylden-Aar” (Eternity’s Golden Year), but can also designate the pleasure derived by earthly life from faith in, and hope for, eternal life or the Church’s vocation and work on earth under rather problematic conditions. Grundtvig also used the term in a worldly context to designate a phase in history. The background for understanding it in this sense is his feeling of being a symbol himself, a prophecy of a renewal of Danish spiritual, ecclesiastical and social life. It was launched in the prologue and epilogue of his poem “Paaske-Lilien” (The Daffodil) of 1817 and repeated with greater force and breadth in his prophetic lay Nyaars-Morgen (New Year’s Morning), 1824. With hindsight we can easily recognize the trait, but his contemporaries barely understood his words and could not accept even what they did understand. As a new approach, he rejected the strategic error of his youth:

the fundamental delusion which I shared with all historical scholars of the post-medieval period, namely that by immersing oneself in antiquity one would be able to – and should – bring about a rebirth of its splendour. What I tried to do was termed folly, because I endeavoured to invoke, not the so-called ‘Classical Era’ and especially the ‘Golden Age’ of Augustus, but the heathen times and Middles Ages of the North.

Instead – especially after his visits to England – Grundtvig explored his own society in order to examine its organization and influence its development. In Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre (Wilhelm Meister’s Apprentice Years), which Grundtvig read in May-June 1803 in Rahbek’s translation of 1801- 02, Lothario, who has returned from an abortive attempt to become an American, declares: “Hier, oder nirgend ist Amerika!” (Here, or nowhere, is America!). In the same style, Grundtvig now began to say, time and again: “Here, or nowhere, the Golden Year will come.”

Under Frederik VI the king’s person became a symbol of a golden age to a degree unparalleled under any earlier or later absolute monarch in Denmark. This was due to a combination of his personality, his long reign (55 years) and the tremendous expansion of printed literature, particularly newspapers and periodicals. His life gradually took on the character of a modern myth, at all events in public ceremonials and apparently also in the minds of the people as a whole.

This is exemplified by his triumphal return on 1 June 1815 from the Congress of Vienna, when it was widely felt that he had saved the nation’s independence. After finally having let himself be anointed as king on 31 July that same year (rather conveniently from the point of view of the royal household, on his silver wedding day), Frederik VI declined expensive festivities in his own honour for the rest of his life. Despite his lofty view of the hereditary monarchy he was sufficiently straightforward and down to earth not to believe in flattery, preferring to spend money on helping the poor and other deserving causes. The public feeling that his reign was a golden age therefore found few possibilities of being displayed in areas outside the obligatory occasional poems and the Royal Theatre, whose rear stalls represented a usable – and much used – safety valve for public opinion prior to the June Constitution’s abolition of censorship of printed matter. By his own account the king actually experienced the best evening of his life at the theatre on 7 October 1830, when the audience demonstratively applauded him after the performance of Den Stumme i Portici (The Mute Girl of Portici, or Masaniello), the opera by D. F. Auber that had provoked a rebellion in Brussels on 25 August that same year and subsequently the formation of the state of Belgium. Copenhagen’s civil servants and purveyors by appointment to the royal court were obviously anxious to uphold the Danish absolute monarchy, but the existence during this period of a genuine affection for the king and his family should not be disregarded.

A final major manifestation of this affection occurred in 1833 and inspired Grundtvig to a ‘golden year’ poem six months later. In July the king had been very seriously ill at Louisenlund Palace on the Schlei Fiord, but had returned in August, apparently fully recovered, to Copenhagen. Details of the mood that prevailed have been preserved in a few commentaries. The king had left Louisenlund at 7 o’clock in the morning of Friday, 2 August, and been accompanied to Schleimunde by the Duke and Duchess of Glücksborg and their children. The weather was “beautiful and agreeable for steamship travel”, but the small, not particularly comfortable royal yacht Kiel nevertheless anchored up for the night off Ulfshale (the northern tip of the island of Møn). On Saturday morning the voyage continued towards Copenhagen, encountering stormy weather and heavy seas in the Bay of Køge. The arrival of the royal yacht had been awaited excitedly in Copenhagen. At half-past four in the afternoon the Kiel was able to cast anchor in the roads under a cloudless sky. The queen came out to meet her husband in a barge.

All that Saturday the people of Copenhagen had set aside their work and business and excitedly “kept a look-out, from the houses, towers and embankments, from the Customs House, from mast-tops, and from the coasts of Amager and Zealand”. When the cry was finally heard “The steamship is now visible in the sea!” everybody rushed down to the harbor as if the whole crowd formed but one body, with thousands upon thousands of heads. But when the royal yacht was finally espied, advancing proudly behind Nyholm’s bastions, when it sped past [the naval fortresses of] Lunette and Trekroner as if fate once more would threaten Denmark with the loss of its Palladium, but now turned inwards again, into the country’s and the nation’s open embrace, the whole world should then have witnessed the feelings they expressed, which rose to what I cannot describe, to quiet worship, when “The King! The King himself!” could be seen descending into the barge.

People stared, “for the rumour had even spread that the king was dead”, and their eyes were filled with tears:

Then gentlemen could be seen embracing and shaking hands with those nearest to them, sailors in their blouses, working men and simple citizens. It was a scene that should have been immortalized by the greatest painters

had these, at the sight, been able to do anything but weep:

As the sloop now approached, the emotions of many dissolved into joyful shouts of happiness; but thousands of the best lips fell silent, tears were violently restrained, until the little blue cap, swung by his own hand, appeared outside the sloop’s tent curtains.

When the royal couple had assumed their places in the royal carriage the king permitted the horses to be taken out of the shafts so that people might pull it to Amalienborg Palace “amidst cheers and shouts of joy and the swinging of hats”, or, as Adresseavisen (the Advertisement Paper) expressed it more poetically in a front page column before the advertisements, “he was borne safely to the Royal Castle on the hands of the [capital’s] inhabitants”. The king had to step forward on the balcony in order to acknowledge the ovations. In the evening it pleased him and his family to drive through the main streets of the city to see his subjects’ illuminations. The festivities continued during the following days, including student processions and military parades. Under the pseudonym “A Voice from the People”, one writer assured readers that a king should be like a father for “the big national family”, and that the people, “the naturally thinking, least corrupted mass”, should cling to him, thereby demonstrating a love that surpassed every other human emotion. “The world has never seen anything more beautiful”, claimed the loyal eye-witness: the people, impelled by “the most sincere, completely voluntary, child-like and yet so conscious feeling of loving affection, loyalty and gratitude” held “a great divine service in the Temple of the Lord on the coast of the Sound!!!” Grundtvig, who was no doubt also present, gave an account of the interplay between monarch and people in stanza 37 of a poem from 1834 as follows:

And then a voice was raised

A word was heard on high,

That no better could belong

In any place on earth.

The king, most deeply moved,

Now felt himself revived,

And born anew a king!

Later in the poem, using a typographically emphasized play on words Grundtvig asserted that “Det var en deilig Scene, / Men intet Skue-Spil” (It was a lovely scene, / But not an acted play” (stanza 37)).

On the very day of the royal arrival the event prompted in the press a public subscription for a commemorative medal which despite a number of accidents in the course of production, It was possible to present to the royal couple on the anniversary of their return (fig. 65). The obverse showed the king in profile, the reverse the city of Copenhagen in the shape of a woman with a brick crown making offerings to a statue of Hygeia, the goddess of health placed on a high pedestal in front of a burning alta; with an Aesculapian staff (Hygeia was the daughter of the Greek god of medicine, Asklepios).

Not only Grundtvig himself but also his three children were among the almost 1,700 Copenhagen contributors to the project; but perhaps he was disappointed at the use of Greek instead of Nordic mythology.

This was certainly not the case with Grundtvigs own monument to the king a poem of 73 solid stanzas printed in Den nordiske Kirketidende (The Nordic Church Times) on 26 January 1834 under the title “Gylden-Aaret” (The Golden Year). Its purpose, recalling the commemorative medal, was to mark not only the king’s 50th Jubilee on 14 April but also his birthday two days later. It includes many details from Nordic mythology and the history of Danish legends, but no figures from antiquity apart from the nine muses in stanza 50, which are identified with Heimdal’s nine mother’s, the “wave maidens”.

In this poem Grundtvig addressed the new year, 1834, as a little child in its cradle who in middle age would crown the king and finally go to its Father – 1833, that is – in “Ærens Høie-Loft” (the hall of honour) (stanza 3). 1834 was therefore a national golden year, and the qualities which made Frederik VI’s rule praiseworthy were the principal themes of the year and the poem. Grundtvig touched on the anticipated medal commemorating the king’s recent cure and triumphal return (stanzas 6-7, cf. 35-36), which was then being worked on. But apparently he did not know the details of the plan for the medal’s decoration. He imagined that on the one side it would portray the ship of fortune on a stormless, waveless sea, all sails set, being propelled “leisurely”, by “the power of heat” (stanza 10). Like all other steam-propelled ships of the day, the royal yacht also carried sails. The heat could obviously apply on the one hand to the steam from its engine, but on the other also to the Danes’ love for their ruler – and furthermore there is probably a reference to the legendary little king Skjold (Shield), who brought Denmark royal fortune when the country needed a regent. On the other side of the medal Grundtvig imagined the king with a wreath of golden ears of corn on his silver-white hair. As the following stanzas (13-15, cf. 17) show, this plays on Thomas Thaarup’s Singspiel Høst-Gildet (The Harvest Festival) performed on the occasion of the crown prince’s wedding in 1790.

In the main section of the poem Grundtvig looked back on Frederik VI’s life as he himself had seen it, starting with the wise young regent’s assumption of rule ( 1784), moving on to the wedding festivities (1790) , when Thaarup’s popular songs heralded a revival of the mother tongue and renewed respect for the Danish language, and thence to the present, when the king was to reap what had then been sown. Grundtvig emphasized the contrast between the peaceful social and economic reforms of 1784-88 and the bloody French Revolution of 1789. He compared the heroic Battle of Copenhagen in 180l to the cremation of the Nordic god Balder, and emphasized that this event bore a “son of pain” (stanza 30), namely the intellectual life of the new century. This culture was called, with yet another term from Norse mythology, a “Forsete who smooths out all quarrels” (stanza 32); this little known god, whose name means ‘chairman’, was the Aesir’s conciliator. The son of pain and the founder of peace had now come of age in 1834 and would establish good conditions for the Danes.

At this point the poem proceeded to request the king to found a Folk High School at Sorø – a regular feature in Grundtvig’s writings from the 1830s and 40s. Further, Grundtvig drew attention to the combination of deed and poem: for 50 years Frederik VI had had his praises sung by a choir of skalds in a fashion unparalleled in Danish history since Hjarne sang the praises of Frode Fredegod (an episode mentioned in the 6th Book of Saxo’s History of Denmark from around 1200). In short, under Frederik VI, Scandinavian spirituality regained its voice, and this voice was more than an “after-blast” (stanza 63) , a mere superficial echo of the olden days. In ancient writings – and here Grundtvig is probably thinking of his own translations from 1815-23 of Snorri, Saxo and Beowulf, Scandinavian spirituality found its best way of expressing “What deep in the heart / May still rouse joy and pain” (stanza 63) The noble thoughts and resonances of the poems were echoed on the throne and in the king’s breast: “It was a tonal meeting/ Of the living and the dead, / As in a Golden Year!” (stanza 67) . Grundtvig continued in stanza 68 with an unspecified description of the writers of the Golden Age, for some were strong, and some were mild:

“One hard, another tender, / One clear as gold

and amber, / One like the ocean, dark and deep, /

One soaring as the eagle’s flight!”.

At the end of the poem Grundtvig expressed the wish that the golden year 1834 might have God’s blessing in order to reveal the richness of the Danish heart in an interplay between the king and his people. Peace abroad, enlightenment of the people at home, a period of flowering for the Danish language and Danish literature – these were the elements from which the secular Golden Year would grow forth.

On the day of Frederik VI’s funeral, 15 Januar 1840, Grundtvig made a speech in the Danske Samfund in which he proclaimed the king’s era to have been a golden age “that was in our midst although we did not recognize it”. It is an allusion to the words of John the Baptist about Christ (John 1 : 26) and apparently suggests a reappraisal of the immediate present, which Grundtvig until then had regarded with both criticism and revulsion. On the king’s birthday a fortnight later Grundtvig remembered him, again in the Danske Samfund, for what he had done for the Danish language, communal singing and history, and looked forward to a strengthening of the king’s posthumous reputation as “a popular king”. In an accompanying poem Grundtvig referred to himself as a bard crowing like a cock in the morning: “Loudly I flap my wings / In the dawn of a Golden Year”.

Notwithstanding the enormity of the national catastrophes he had experienced, Grundtvig interpreted them as birth pains rather than death throes. This applies to a marked extent to the two Slesvig wars, in 1848-50 and 1864. In his poetic universe he worked with stylized concepts in order to express the content of a Golden Year. In his poem “Asa-Maalet og Kæmpe Visen” the Aesir Tongue and Medieval Ballad) from november 1849 he suggested that the Danes once more should give the old Nordic lays and Danish folk ballads “a warm home”. The Edda lays represented the common Nordic heritage with a twinborn undertone consisting of the struggle for life and a longing for peace. Their symbol was Bragi god of poetry and eloquence, with his golden harp. The folk ballads represented a paean from the depths a “sorrow with joy”, just as when mermaids sang “halfway between their smiles and fears!” (stanza 6) . They were personified by the goddess Idun with the golden apples that could uphold and restore youth (fig. 66). In Nordic mythology these two were indeed a lovely man and wife – he the brain and she the heart (stanza 9). Grundtvig stressed that the Nordic and the masculine should be united with the Danish and the feminine (stanza 36): the war-god Odin’s dwelling, Valhalla, and the goddess of love Freyja’s abode, Folkvang, were both to be recreated in the same way that fields in the springtime become green again. The combination of rose-bloom and heroic lay promised a new Nordic Golden Year.

These blasts from Grundtvig’s pen have little to do with the Danish capital’s cultivation of an intimate and refined mood in subdued poetry and art. To his way of thinking, ‘golden age’ and ‘golden year’ were solid elements that concerned the whole population, in the past, the present and in the future. They embraced energy that should be invoked and utilized. In this respect he differed from the majority of his colleagues.

Grundtvig’s poem “Ønske-Møen” ( The Wish Maiden) from February 1850 describes the mythological Nordic goddess Fylla. She was the friend of Balder’s mother Frigg, and her task was to arouse the wish “Until in Denmark’s Golden Year/ It blissfully belaid to rest” – because by then it would have been fulfilled. He followed it up in May that same year with the poem “Danmarks Gyldenaar” (Denmark’s Golden Year) in which he saw the beechwoods that had just burst into leaf as a sign that God would send Denmark a long, golden year as beautiful as the midsummer.

An after-effect of Oehlenschlager’s death and burial in January 1850 can be noted in an article in Danskeren ( The Dane) of 2 March entitled “Guld-Alderen og Grotte-Sangen i Danmark” (The Golden Age and the Grotta Song [an old Icelandic lay] in Denmark) . By way of introduction Grundtvig wrote ironically about the laments of the time over the loss of the prince of poets. He found Oehlenschlager as a man and producer of books less interesting than the historical place he occupied. In the course of history the great prince of poets was, he claimed, the very “human spirit” whose childhood and youth lay in the golden and silver ages of grey antiquity. With Oehlenschläger this human spirit enjoyed a resurgence in an age of iron – or rather, of paper; he applied “a genuine layer of gilt to the Iron Age in everything so that it could justly be called a ‘Golden Year”’. Therefore one should repudiate those who claimed that

the Golden Age was but a foolish, childish dream, which they thank their good sense and reason for not having believed in, or taken the slightest notice of, even as children, adding with a haughty mien that even gold’s reputation as the noblest metal is but a cloud of smoke that vanishes the moment it is puffed at, for well-consolidated government bonds are at all times just as good at “the reddest gold”, and, when quoted on the Stock Exchange for their owners, even better, being insured against the grasping hands of thieves and many other eventualities.

Faced with such a superficial outlook, Grundtvig had to emphasize that because gold has three great advantages compared with paper, namely brilliance, resonance and durability, it is “a peerless image of a life and a period which, in a superior human sense, possess the same qualities”. For this reason, those who neither believe in a golden age in the past, nor in a golden year in the future, behave foolishly.

The Danish Golden Year, Grundtvig continued, might be expected to arrive because the Danes had still retained the three principal elements in the life of a nation, these being a sense of patriotism, a mother tongue and friendly solidarity. This engendered hope for a Golden Year, which even in a nation’s old age corresponded to its Golden Age. This hope lay behind Grundtvig’s frequent comparisons between the reigning Danish king at any given time and king Skjold, Frode Fredegod and some of Denmark’s other ancient kings. He therefore concluded by prophesying a new dawn over the plain, that is to say Denmark, “a dawn of freedom and deed” aroused by Frederik VII’s accession to the throne, but clearly prepared by his predecessors Frederik VI and Christian VIII.

What Grundtvig wished for Denmark was a new Frode Fredegod period marked by peace, justice and in particular that happiness which in Denmark’s history had always been better than reason. Against this background he fully agreed that the Danes should reject worldly “honour and power, wisdom and cunning, admiration and renown”.

These characteristics had no place in an approaching Danish ‘golden year’. In Grundtvig’s view the aim should rather be to make people’s everyday lives golden. He emphasized this in his Haandbog i Verdens-Historien, Ill, 1843(-56). In connection with the Italian Renaissance he wrote:

the correct art of governing consists, with the common good constantly in mind, in developing a people’s energies into the greatest and most beneficial form of activity to which they are equal without wishing on any point whatsoever to force a clarity which is only of value when it comes of its own accord, which it always does when the activity lives to the end of its natural span; for then it becomes, of necessity, aware of itself, whilst every other form of so-called clarity is no more than empty delusion.

The great art consisted in “creating a free and beautiful citizen community of living people”, whereas handling words, tones, stones and colours in a beautiful way was a far easier matter. Grundtvig’s conclusion was therefore

that whereas all the fine arts are merely wasted on an ugly life, on the other hand a beautiful human life will in itself beautify its surroundings and everything it comes into contact with, so that the difference will only be the same as that which arises between natural and painted rosy cheeks, or at any rate between hothouse plants and such growths and fruits that develop later but are much juicier, stronger, last longer and are more suitable for the season in “free soil under an open sky”.

Could it be that Grundtvig regarded part of Denmark’s Golden Age culture as an artificially forced hothouse plant?

True art for Grundtvig was a question of arranging one’s own existence and that of others in society, not the worship of enthralling illusions. He expressed this even more directly in 1844 when he claimed that the proverb ‘wonders will never cease’ (as a sailor is said to have shouted at Thorvaldsen’s funeral) has long been known, and it is probably the general opinion everywhere. However it is only in connection with very few things that I have the pleasure to share what at present is the ‘general opinion’, and among them is not the fact that wonders never cease, insofar as what concerns us in this case is by no means the small everyday wonders, and by no means merely the fine arts created by human hands, but in particular the great art of the intellect and the heart to ‘beautify life’, thus imitating the peerless Artist who creates ‘living beauty’.

Unfortunately, Grundtvig continued, this art has been lost amongst statesmen, but by imitating the ancient Greeks and with the help of poets and women (none of whom are as yet represented in modern politics), it can be recovered so that we learn anew

to work on what can be done, that is, not on recreating, or improving, but only on calming and beautifying life! It so happens that the former exceeds, as reason indicates, all human power, reason and understanding, so that in this way one merely makes matters worse and, as far as possible, what is good, bad, whereas experience teaches us that the latter can be most wondrously achieved.

This applied in particular if one could liberate oneself from the prejudice that beauty presupposes the very strictest order at the expense of freedom, life and the best abilities, for

no work can in any possible way become greater than the force which produces it, and the experience of millennia teaches us that all the noble forces of human nature thrive only in freedom and wither away in thraldom. The real issue as far as Grundtvig was concerned Was the discovery of the true identity of the people, ‘) expressed through a Danish community way of life, plain, cheerful and active – the plain as a counterpart to the boastful, the cheerful to the sulky, the active to the drowsy. This way of life, and not a cultivation of the the activities of a cultural elite, constituted the true ‘golden age’, which Grundtvig nearly always rechristened a ‘golden year’ and placed in the near future.

He did so again in 1864. His poem in commemoration of Frederik VII was called “Danmarks Guldalder og Gylden-Aar” (Denmark’s Golden Age and Golden Year) and compared – a month before the shocking retreat from Dannevirke – Balder’s and Frode’s golden age with the golden years under Frederik VI and Frederik VII. In his cycle of poems Nordens Myther (Myths of the North), written after the defeat in that same year, when the military and political catastrophe weighed heavily upon the whole country, but not published until 1930, he let the Nordic goddess of love, Freyja, weep tears of longing for her vanished husband as an image of an amputated Denmark. Characteristically, however, here he was also able to convert the pain of death throes into birth pains and turn the misfortune into a hope of resurrection. For Freyja’s tears – according to Snorri’s Edda – were of gold, her heart wounds smelled of roses and the smile of joy could be seen through the veil of sorrow.

Grundtvig saw this attitude as being typically Danish. He saw Denmark preferably in the figure of a woman – be it the Freyja of Nordic mythology, the mermaid of the folk ballads, or the New Testament’s widow of Nain – or all in one. He saw Denmark in the perspective of world history as a historic idyll – just as Thaarup had represented it in Høst-Gildet – “indescribably lovely”. In the same way that ancient Greece was the home of the idyll and the idyllic poetry that takes place in nature, Denmark was the country of the historic idyll. It was demonstrated not only by Thaarup but also in the folk ballads:

Their soul is hero-love, which brings forth only historic, idyllic scenes insofar that a historical event fills the fo reground and breathes significance into the everyday, quiet, fr iendly life whereby, in conjunction with the heroic life, it becomes deeply poetic.

Grundtvig wrote these words to Ingemann on 5 October 1823 when the two fr iends were corresponding about Ingemann’s work on his epic poem about the Danish Middle Ages “Waldemar den Store og hans Mænd” (Waldemar the Great and His Men), which was published the following year. Instead of Valdemar, Absalon and Esbern Snare, Grundtvig would have preferred a description of the heroes childhood homes and seen “the interior at Fjenneslevlille where Absalon’s mother and his siblings lived, the house where the heroic heart evidently belonged”.

In his Mands Minde lectures in 1838 he burst out, happily surprised to be able to mention the Copenhagen Liberty Memorial (fig. 67) in the same breath as the French Revolution’s Tree of Liberty: “It is strange how idyllically everything historic manifests and unites itself in Denmark.” Both the memorial and Thaarup’s Singspiel came to express

in the most natural way in the world the relationship between the free peasant and the citizenry of the capital, indeed it became a lovely omen of the fine yet natural Danish taste that would develop in the Peasant Era in the course of a living interplay between rural areas and the capital.

In 1838, slightly more than halfway through life, Grundtvig himself had changed his approach. By placing increasingly greater emphasis on the farming class and the rural population he was approaching a national-cum-Christian cultural synthesis that was to grow into a movement of hitherto unknown strength in Denmark. In the last of these Mands Minde lectures, given on 26 November 1838, he spoke of his own endeavours to find a more conciliatory attitude regarding the struggles and conflicts in which he had hitherto allowed himself to become embroiled:

It so happens that I have abandoned my old claim: the more struggle, the more life. I realize now it should be: the more struggle, the more life in danger, which may result in: more death. It therefore applies in all respects that a paltry settlement out of court is better than being awarded fat damages in court … and that the spur which is necessary to peaceful activity is procured by an open race rather than by hostilities – and one for human beings, not a horse-race.

In this way he created a background for what was after all, a peaceful political way of life characteristic of the Danish social and political pattern after the June Constitution of 1849. Those who grew up with it perhaps failed to see it that clearly, but foreign scholars who have studied Danish culture regard this placidity with both wonderment and admiration and tend to regard Grundtvig’s contribution as one of its explanations.

Grundtvig himself believed that Denmark’s destiny in his own lifetime could guide all other nations. In 1869 he concluded the publication of his prodigious Haandbog i Verdens-Historie with a meagre 15-page supplement about the period 1715-1866 in which he noted that because of the Danes (the Battle of Copenhagen) and the Greeks (their rebellion against the Turks), the nineteenth century was a “golden year in which peoples realized their national identity”. Denmark’s severe trials – in 1807, 1814, 1848 and 1864 – had after all developed and spread such a spirited and bright view of mankind in all its national, ecclesiastical and scientific contexts, which throughout Christendom can and surely will give to all peoples a Golden Year in which enlightenment of life will oust all the literary jack-o’ -lanterns and show the world what peoples have been created for and are capable of.

From Golden Age to Golden Year

During the Danish Golden Age, as the term is normally understood nowadays during festive weeks and ‘Cultural Capital of Europe’ celebrations, Grundtvig was an outsider.

The operetta -like Copenhagen one all too easily associates with the Golden Age was certainly not the Copenhagen Grundtvig saw. The Tivoli Gardens, plucky Danish soldiers, public holidays being celebrated on the ramparts, balls, ballets and vaudevilles, all passed over his head. He lacked the Copenhageners’ lightheartedness and appetite for harmless diversions.

The earnestly lofty – Oehlenschlager’s preferred element in tragedies and occasional poems – held no appeal for him either. As a young man Grundtvig had been a totally unenthusiastic member of Kronprindsens Livcorps ( The Crown Prince’s Life Corps) during the Battle of Copenhagen, which he had watched, in Oehlenschlager’s company and without poetic exaltation, from a balcony in the aristocratic Bredgade quarter and also from Langelinie, Copenhageners’ favourite promenade along the harbor front. On the other hand, in January 1814 he switched right over to exaggerated pathos at the Twelfth Night mobilization of Copenhagen’s students, which the king had been unable to make any use of and was moreover regarded by more dispassionate contemporary observers as touching on the parodic.

Grundtvig later sought genuinely Danish and Copenhagen characteristics in a more peaceful and ordinary road, Strandvejen (the Coast Road) north of Copenhagen. With his penetrating gaze he noted the symbolism in the capital’s position between the Sound at Kongedybet (the Royal Fairway outside the harbour, where the Battle of Copenhagen took place in 1801) and Charlottenlund with its spreading beech trees. Here was the pledge of a Danish future:

Greatness and loveliness must actually merge, life and innovation unite in the victorious nature which must be able to take up the struggle against a capital’s tastefully concealed and garnished artificiality, and even more against the artificial play of nature’s lively shadows, which so easily appear to be both lovelier and richer than nature herself; but where greatness and loveliness merge so splendidly in our Strandvej, where the sea espouses the beechwoods, the waves sing bass in the birds’ choir and the ships, which bring novelties and inspire activity, at the same time invigorate and constantly transform the views …

that was where one could obtain the genuine historical and idyllic impression. The splendid thing about Thaarup’s old, half-forgotten Singspiel was its very combination of “the natural and the historical, the real and the dreamed, the everyday and the ceremonial, the simple and the majestic, the popular and the royal”.

On the strength of this sharp-eyed appraisal of the Danish national character Grundtvig perhaps deserves after all to be acknowledged as part of Copenhagen’s Golden Age. Many of the writers and artists of the time cultivated interiors, children, domestic animals, gardens, chicken pens and, when aiming really high, the narrow lane and woods just outside. Grundtvig provides this intimate and nearsighted idyll with a much-needed expansion, supplementing it with the big world and interpreting the union as a symbol of a secular golden year of peace, justice and above all happiness, the Danes’ specific element. And for Grundtvig, happiness was above all inherent in the feminine. It is therefore significant that he should have seized the comparatively new understanding at the time for the home, the family and the female sex as the preserves of sincerity, mildness and love – in short, the most genuinely human and at the same time closest to God’s finest creations. His achievement was having the courage to reformulate this understanding so as to apply it to Denmark’s God-given place in the history of the world. Just as women were hjerte-ligere ( ,more heart-like’, i.e. warmer, sincerer) than men, Denmark was a kvindfolk (female people), hjertefolket (the people of the heart) , God’s own country in the new era.

In fact this feeling could even be transposed to the religious. When Grundtvig in 1836 was to compose for his Sang-Værk a new Danish version of the 85th Psalm of David about the longing for God’s dwellings he first wrote “Munter og rolig” (Cheerful and peaceful), thought better of it and changed it to “Hyggelig, rolig, / Gud! er din Bolig” (Cosy and peaceful, / God! is thy dwelling) and then also changed the following line from “elskelig” ( amiable), the psalm’s introductory Danish adjective in older translations of the Bible, to “Inderlig skiøn” (Profoundly

beautiful).

If he was able to associate the Old Testament’s Lord of Hosts with the untranslatable Danish term hygge, then perhaps he must have had some roots in the gentle Danish Golden Age after all (see fig. 17, p. 34).

The local, the intimate and the close are favourite categories in culture. This is borne out by little gems such as J. L. Heiberg’s national drama Elverhøj (Elfin Hill) and H. Hertz’s Copenhagen comedy Sparekassen (The Savings Bank) , Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales and Ingemann’s morning and evening songs for children, H. V. Kaalund’s versified animal fables and August Bournonville’s ballets, Købke’s paintings and Lundbye’s drawings. Grundtvig was not incapable of appreciating this small world, but succeeded, without destroying its accurate picture of familiar everyday life, in giving it the greatest historical, ecclesiastical and religious dimensions. For him, the Golden Age became inevitably a Golden Year.

Last updated 11.05.2017