Brera in Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Times

- Elisabetta Bianchi, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2021

The article is one out of two talks given at Thorvaldsen’s Museum at October 7th 2021, in connection to the special exhibition «Longings: Thorvaldsen’s Italian Paintings» under the main title Milan and Pinacoteca di Brera in Bertel Thorvaldsen’s time. The other talk by Chiara Battezzati is also found here in the archives.

When you will come to visit Brera, you will find yourself immersed in a vibrant neighborhood, with the Palazzo di Brera situated in its very heart. The building is home to several institutions which still coexist, just like they did in the past: among them there are the Academy of Fine Arts, The Braidense National Library and the Pinacoteca, which has been extensively refurbished in recent years under the direction of James Bradburne. The display of the works, the lighting, the colors of the walls, the captions, the café, all have been renewed.

ORIGINS AND GROWTH OF THE COLLECTIONS

The Brera complex has medieval origins: since 1201 it was the seat of the religious congregation of the Humiliati, who had their own church, Santa Maria di Brera. In 1571 the Jesuits took over and turned it into a school. With the advent of Maria Theresa of Austria and the suppression of the Jesuit order, the building became the seat of secular education and underwent some radical changes. In 1776 Maria Theresa founded the local Academy of Fine Arts, thus fostering the creation of an extraordinarily modern citadel of culture. In the Brera courtyard young and old people would meet and be open to mutual exchange (the historian Pietro Verri affirmed that “in Brera I feel as if I were in an educated country”).

14. Domenico Aspari, View of the Main Courtyard of Brera, engraving, 1789, Milan, Civica Raccolta delle Stampe Achille Bertarelli, Castello Sforzesco, Albo K 4 bis, tav. 1

The first nucleus of the art collection was formed at the end of the 18th century and came from the suppression of the religious orders. At first it was intended to provide inspiration for the Academy students, but with the passage from the Austrian to the French government, in 1796, and with Giuseppe Bossi, Andrea Appiani and the viceroy Eugene de Beauharnais (Napoleon’s stepson), the Pinacoteca became a collection of works not only intended for the training of the budding artists but also for the education of citizens.

In 1805 Napoleon was crowned King of Italy in the Cathedral of Milan, the city that had been chosen as the capital of his kingdom (Brera owns the mantle, the crown and the scepter used during the coronation in Milan). Compared to other towns, Milan enjoyed a position of absolute privilege, and hundreds of artworks selected by Appiani from the looting of the conquered territories started coming to Brera.

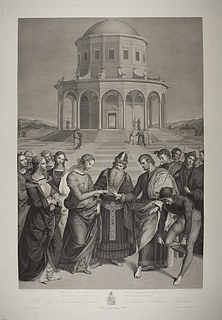

In 1806 Eugene de Beauharnais donated the Marriage of the Virgin by Raphael, thus confirming Milan’s political and symbolic importance. Raphael’s altarpiece had been officially “donated” to a general of the French army, but unofficially stolen from Città di Castello, a town in Central Italy, and later purchased by the viceroy as a gift to Brera.

15. Raffaello Sanzio (Raphael), The Marriage of the Virgin, oil on panel, 1504, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

In 1806 Bossi organized the very first public presentation of the collections. After Bossi, Appiani managed the ever-growing collection alongside the viceroy.

The number of paintings acquired through looting was so high that in 1808 the Gothic façade of the church of Santa Maria di Brera was sacrificed in order to expand the Pinacoteca, with the creation of 4 large square rooms illuminated by skylights. The first 3 rooms of the “Real Galleria” housed 139 paintings and were opened to the public on August the 15, 1809, on the occasion of Napoleon’s birthday. This doesn’t have to be considered a real inauguration, rather a low-key and temporary presentation: Napoleon and the viceroy were not present and the works were still ongoing.

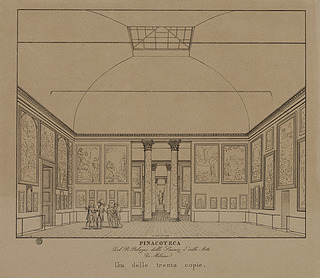

Thanks to the engraving made in 1812 combined with some documents, we know that the setup complied with the Neoclassical criteria of symmetry: the paintings were not displayed in chronological order but rather according to their iconography and correspondence in size.

16. Michele Bisi, Pinacoteca del R. Palazzo delle Scienze e delle Arti di Milano, Milan, Civica Raccolta delle Stampe Achille Bertarelli, Castello Sforzesco, P.V. m. 8-51

Just like what had been done in the Louvre, the small paintings were displayed at the bottom, while the large ones at the top. We also know that the walls had been painted green (the same color that was picked for the most recent refurbishment), and that the glossy stucco columns were made to imitate marble and were crowned with golden capitals.

The engraving also shows that the colossal-scale plaster cast of Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker by Antonio Canova was housed at the very end of the row of the halls, with a highly symbolic meaning. It had been purchased in Rome by the viceroy specifically for Brera at the urging of Bossi (today we can admire it in the Gallery, in a central position while the bronze version stands in the center of the Brera Courtyard).

17. Antonio Canova, Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker, plaster cast, 1807, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

Between 1811 and 1813, an impressive number of paintings reached Milan, both from Veneto and central Italian regions. The collection thus reached 889 paintings, only about 350 of which were put on display.

It is interesting to point out that the definitive fall of Napoleon, in 1814, had very few repercussions on Brera: the collection underwent very small reductions.

THORVALDSEN AND BRERA: 1819, 1832, 1841

Thorvaldsen had been an honorary member of the Brera Academy since 1811 and when he visited Brera neither the building nor the museum looked as they do today.

The Cortile d’Onore still had no sculptures, nor did it house the imposing bronze statue of Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker. Thorvaldsen could not either see the bronze version and the plaster cast (both by Canova): due to several reasons, the bronze was placed in the Main Courtyard only in 1859, while the plaster cast, a few years after the inauguration, was removed from the Gallery and forgotten in the warehouses, due to the fall of Napoleon (it was repositioned in the museum in 2009).

18. Brera Main Courtyard with the bronze by Antonio Canova Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker, 1808

Here follows a telling testimony for the impression that the Pinacoteca made on a foreign visitor in 1820, according to the notes by Dorothy Wordsworth, visiting with her poet brother William, she wrote: “The gallery of the Emperor’s paintings is a succession of imposing rooms, with ceilings supported by high and well-proportioned yellow-veined marble columns: London has nothing that deserves the name of an art gallery, like this one.”

To gain better understanding of mid-19th century taste, we must rely on sources such as prints after paintings. In an era when photography did not exist, the most admired artworks were in fact reproduced in prints as postcards in our days. In Milan, print-collecting was thriving: Bossi, for example, owned over 2300 prints, many of which reproduces Raphael’s works. Thorvaldsen himself owned both several paintings and prints made as copies after Raphael’s masterpieces, including a print of the Marriage of the Virgin at Brera:

19. Pietro Folo, Sposalizio (The Marriage of the Virgin), engraving, 1831. After Raphael’s painting. Published by Nicola Bianchi impresse. Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum, inv. E530

In the 19th century, Raphael was regarded with great veneration. Brera’s Marriage of the Virgin was executed in 1504 for the church of Saint Francis in Città di Castello. As a model Raphael used the altarpiece with the same subject painted shortly before by Perugino (now kept in Caen, Musée des Beaux Arts).

Both Perugino and Raphael chose not to set the episode inside the temple, but rather in an open square. Though, while Perugino’s painting is marked by 3 bands that define the composition’s depth – foreground, middle ground and background – Raphael’s scene is built using the temple as pivot, as the fulcrum of a three-dimensional space which finds its vanishing point in the building’s open door.

Each element of the composition is balanced, even the colors, in the play between warm and cold hues, but what today’s and yesterday’s observers first perceive is the naturalness and simplicity in perfection. Raphael surpasses the older Perugino, providing, for centuries to come, the crystallization of the idea of Beauty, superior even to the beauty of Nature.

Bossi had strongly encouraged the purchase of this painting, that he identified as a prototype for the education of young artists.

To give an even better idea of how taste then was different, we must bear in mind that at the turn of the 19th century in the Louvre, Raphael’s Saint Cecilia (now in Bologna) was far more appreciated than Leonardo’s Mona Lisa.

Speaking of Leonardo: in 1809, Raphael’s Marriage was displayed alongside works attributed to Leonardo and his circle, such as the Three Archangels by Marco d’Oggiono, the Madonna and the Child with Saints by Bernardino Zenale, and other paintings by still anonymous Leonardesque artists. As for Leonardo’s masterpiece the Last Supper, Eugene de Beauharnais had commissioned a full-size copy of it (now lost) to Bossi which immediately was put on display in Brera, where it was highly praised: for example, the vicereine Amalia Augusta of Bavaria specifically came in Pinacoteca to admire it. Interest in Leonardo was very high in Milan and certainly influenced Thorvaldsen, who in fact owned several prints and drawings derived from the Last Supper.

20. Raffaello Morghen, The Last Supper, engraving 1800. After Teodoro Matteini’s drawing after Leonardo da Vinci’s fresco. Published by Nicolaus de Antory. Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum, inv. E845

A peculiarity of Brera, which generates admiration, is the section dedicated to Lombard detached frescoes, that was initially set up during the Napoleonic years. Many of these frescoes are by Bernardino Luini, considered the most famous Lombard painter of the Renaissance. Some of these frescoes are dedicated to religious subjects, while others to profane subjects, such as, for example, the sensual and joyful bathing nymphs, a mythological scene which formerly decorated the private Villa Pelucca:

21. Bernardino Luini, Nymphs Bathing, fresco tranferred to panel, 1514 ca., Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

In 1812, on a visit to Brera, Josephine de Beauharnais (the viceroy’s mother) wrote to her son: “Not all paintings have the same value, but half a dozen are of rare beauty, especially the frescoes by Luini”.

In those very same years, the Venetian painting section of Brera was already one of the world’s most outstanding. Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria painted by the Bellini brothers in the early 16th century had arrived from Venice. The airy square opens up in front of us like a theatre stage, the backdrop of which is made up of an imaginary church, somewhere in between the Basilica of Saint Mark and an oriental building:

22. Gentile and Giovanni Bellini, St. Mark preaching in Alexandria, oil on canvas, 1504-1507, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

Titian’s Saint Jerome, also came from Venice: in this painting the shape of the saint blends in chromatically with the majestic forest.

23. Tiziano Vecellio (Titian), Penitent St. Jerome, oil on canvas, 1550-1555, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

An outstanding palette, lit up by iridescent hues, which is a typical element of Venetian Renaissance painting characterizes the works by Tintoretto and Veronese:

24. Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti), Discovery of the Body of Saint Mark, oil on canvas, 1562-1566, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

25. Veronese (Paolo Caliari), Baptism of Christ, oil on canvas, 1582, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

All of these paintings have been part of Brera’s collections since the Napoleonic years. In Giovanni Bellini’s Pietà, the composition’s rigid grid of vertical and horizontal lines is accompanied by the moving pain expressed by the play of the hands and faces of the Virgin, Christ and Saint John.

26. Giovanni Bellini, Pietà, tempera on panel, 1460 ca., Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

The latter painting belonged to the Sampieri collection in Bologna, which had been sold to Eugene de Beauharnais in 1811. The collection was made up of famous paintings by great 17th-century classicist painters such as the Carraccis, Guido Reni, Francesco Albani and Guercino.

27. Annibale Carracci, Christ and the Samaritan Woman, oil on canvas, 1594-1595, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

Abraham Casting out Hagar and Ishmael by Guercino, in particular, was a truly iconic painting (much admired by Stendhal, for example), clear and simple in its attitudes and spatial relationships.

28. Guercino (Giovan Francesco Barbieri), Abraham Casting out Hagar and Ishmael, oil on canvas, 1657, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

The Carraccis and their pupils were considered true geniuses of art until at least the mid-19th century: for a visitor of the time these paintings alongside Raphael and Leonardo (and his circle) were absolute must-sees.

Thorvaldsen, however, also had a deep interest in contemporary art: as demonstrated in the exhibition Longings: Thorvaldsen’s Italian Paintings (Copenhagen, Thorvaldsen Museum, April 21st – October 24th, 2021), during his stay in Rome he had mostly purchased 19th-century paintings, and among them many Roman landscapes and genre scenes.

In 1817 at Brera the “Cabinet of modern landscapes” was set up: it was placed between the galleries housing the casts of classical statues and the rooms with paintings. In fact, landscape paintings found more and more consensus among collectors and crowded the popular annual Brera art exhibitions.

In 1832, Thorvaldsen was in Milan and given the exceptional nature of the event, the painter Cesare Poggi rushed to paint his portrait. During his visit to the annual Brera exhibition, Thorvaldsen appreciated Desiderio Cesari’s works and commissioned his own bronze portrait (but once it was finished, he didn’t like it at all).

29. Desiderio Cesari, Portrait of Thorvaldsen, gilded bronze, 1825, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum, inv. G7

But above all, he was struck by a painting by Francesco Hayez, Mary Stuart Condemned to Death, and he commissioned a similar canvas to Hayez, which, however, was never made. In those days collectors competed among themselves to snatch works by Hayez, who was the acclaimed protagonist of Milanese Romantic painting. By requesting one of his pictures, Thorvaldsen proves to be open to new trends in painting.

30. Francesco Hayez, Mary Stuart Condemned to Death, oil on canvas, 1832, Paris, Musée du Louvre, © 2012 Musée du Louvre / Harry Bréjat

Thorvaldsen had already been to Brera a few years earlier, in 1819 – during a stop on his journey from Rome to Copenhagen – to evaluate the best location for the Appiani monument. He had received the commission by a group of distinguished Milanese. The commission had been the occasion of one of the very first clashes between Classicists and Romantics. Lombard sculptor Pompeo Marchesi had proposed a large statue of Appiani in contemporary clothes. This project was opposed by the classicist faction, that instead supported Thorvaldsen. In his allegorical monument, a portrait medallion depicting Appiani is combined with a relief with the Three Graces, a theme derived from antiquity, as dear to Appiani as it was to Thorvaldsen.

For the location, Thorvaldsen chooses the zenith light of the great hall of plasters, where his work would have benefitted from the comparison with the reproductions of ancient sculptures. Thorvaldsen’s bas-reliefs came to Brera from Rome in 1826 and were mounted in the Renaissance-style frame made by local artists.

Despite the lukewarm reception, caused by the long wait and the controversy it sparked, the monument will prove to be one of Thorvaldsen’s most popular masterpieces (its success is also evidenced by the versions in reduced format: bronze version and medals, for example).

31. Bertel Thorvaldsen, Monument to Andrea Appiani, marble, 1826, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

32. Bertel Thorvaldsen, Monument to Andrea Appiani (detail), marble, 1826, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

Thorvaldsen returned to Brera one last time in the summer of 1841. He was an established artist and his pupils took part in the annual exhibitions. In Lombardy he had left some of his most important works.

One of his masterpieces, the frieze depicting The Triumph of Alexander the Great (1816-1828), is still kept in Tremezzo, on Lake Como, on the walls of Giovani Battista Sommariva’s villa (nowadays known as Villa Carlotta). Sommariva, a prominent political figure in Milan during the Napoleonic era (portrayed by Proudhon in a painting held at Brera and also in the frieze, next to Thorvaldsen himself), had commissioned the incredible 33-plate frieze for the hall of his magnificent villa. Though he had spent a considerable part of his money on it, he passed away before ever seeing it completed.

Today we can consider ourselves blatantly lucky as this stunning work of art is just a train ride away from Milan.

References

Short bibliography for both articles

Aurora Scotti: Brera 1776-1815: nascita e sviluppo di una istituzione museale milanese, Firenze 1979.

Annalisa Zanni: “Collezionismo e mercato artistico a Milano: smembramenti, vendite, restauri”, in: Mauro Natale, Alessandra Mottola Molfino (eds.): Zenale e Leonardo. Tradizione e rinnovamento della pittura lombarda, Milano 1982, pp. 243-250.

Maria Cristina Gozzoli, “Maria Stuarda nel momento che sale il patibolo”, in: Maria Cristina Gozzoli, Fernando Mazzocca (eds.): Hayez, Milano 1983, pp. 131-136.

Dyveke Helsted: “Thorvaldsen collezionista di arte moderna”, in: Elena di Majo, Bjarne Jørnaes, Stefano Susinno (eds.): Bertel Thorvaldsen 1770-1844. Uno scultore danese a Roma, Roma 1989, pp. 241-244.

Fernando Mazzocca: “Thorvaldsen e i committenti lombardi”, in: Elena di Majo, Bjarne Jørnaes, Stefano Susinno (eds.): Bertel Thorvaldsen 1770-1844. Uno scultore danese a Roma, Roma 1989, pp. 113-129.

Bjarne Jørnaes: “Thorvaldsen com’era”, in: Elena di Majo, Bjarne Jørnaes, Stefano Susinno (eds.): Bertel Thorvaldsen 1770-1844. Uno scultore danese a Roma, Roma 1989, pp. 25-34.

Fernando Mazzocca: Francesco Hayez. Catalogo ragionato, Milano 1994, pp. 173-174.

Daniele Pescarmona: “I monumenti commemorativi”, in: Giacomo Agosti, Matteo Ceriana (eds.): Le raccolte storiche dell’Accademia di Brera, Firenze 1997, pp. 159-169.

Giuliana Ricci: “Il luogo della cultura, dell’arte e della scienza: Brera”, in: Fernando Mazzocca, Alessandro Morandotti (eds.): La Milano del Giovin Signore. Le arti nel Settecento di Parini, Milano 1999, pp. 172-181.

Johann Wolfgang Goethe: Il Cenacolo di Leonardo, traduzione di Claudio Groff, con uno scritto di Marco Carminati, Milano 2004.

Fernando Mazzocca: “Canova e Milano”, in: Antonio Canova. La cultura figurativa e letteraria dei grandi centri italiani, Bassano del Grappa 2006, pp. 7-13.

Chiara Nenci: “Colla opinione e coll’esempio: Giuseppe Bossi e Canova”, in: Antonio Canova. La cultura figurativa e letteraria dei grandi centri italiani, Bassano del Grappa 2006, pp. 15-21.

Francesca Valli: “Con nostro vantaggio e con vostro onore. Canova e l’Accademia di Brera”, in: Antonio Canova. La cultura figurativa e letteraria dei grandi centri italiani, Bassano del Grappa 2006, pp. 23-30.

Eleonora Carantini (ed.): Milano è una seconda Parigi. Viaggiatori britannici e americani a Milano, Palermo 2007.

Alessandro Morandotti: Il collezionismo in Lombardia. Studi e ricerche tra ’600 e ’800, Milano 2008.

Chiara Battezzati (ed.): Carl Friedrich von Rumohr e l’arte nell’Italia settentrionale, in «Concorso. Arti e lettere», III, 2009, pp. 6-23.

Matteo Ceriana (ed.): Il ritorno di Napoleone. Il gesso di Canova a Brera restaurato, Milano 2009.

Matteo Ceriana, Emanuela Daffra (eds.): Raffaello. Lo Sposalizio della Vergine restaurato, Milano 2009.

Isabella Marelli (ed.): La Sala dei Paesaggi. 1817-1822, Milano 2009.

Luisa Arrigoni: “La fondazione, le collezioni, gli allestimenti”, in Luisa Arrigoni, Valentina Maderna (eds.): Pinacoteca di Brera. Dipinti, Milano 2010, pp. 23-37.

Sandrina Bandera: “La vitalità di una istituzione”, in: Luisa Arrigoni, Valentina Maderna (eds.): Pinacoteca di Brera. Dipinti, Milano 2010, pp. 9-21.

Stefano Grandesso, Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), Milano 2010.

Sandra Sicoli (ed.): Milano 1809. La Pinacoteca di Brera e i musei napoleonici, Milano 2010.

Chiara Battezzati: “Milano. San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore”, in: Giovanni Agosti, Rossana Sacchi, Jacopo Stoppa (eds.): Bernardino Luini e i suoi figli. Itinerari, Milano 2014, pp. 122-147, n. 16.

Chiara Battezzati: “Madonna con il Bambino (Madonna del roseto)”, in: Giovanni Agosti, Jacopo Stoppa (eds.): Bernardino Luini e i suoi figli, Milano, 2014, pp. 168-171, n. 27.

Tommaso Tovaglieri: “Saronno. Santuario della Beata Vergine dei Miracolo”, in: Giovanni Agosti, Rossana Sacchi, Jacopo Stoppa (eds.): Bernardino Luini e i suoi figli. Itinerari, Milano 2014, pp. 185-206, n. 25.

Francesco Leone, Andrea Appiani pittore di Napoleone, Milano 2015.

Omar Cucciniello: “Giuseppe Bossi e la copia dell’Ultima Cena di Leonardo”, in: Fernando Mazzocca, Francesca Tasso, Omar Cucciniello (eds.): Bossi e Goethe. Affinità elettive nel segno di Leonardo, Milano 2016, pp. 107-131.

Emanuela Daffra, Cristina Quattrini, Giovanni Agosti (eds.): Primo Dialogo. Raffaello e Perugino, Milano 2016.

Elena Catra: “Il glorioso e polemico ritorno delle opere d’arte requisite da Napoleone: i Cavalli di San Marco e il Giove Egioco”, in: Fernando Mazzocca, Paola Marini, Roberto de Feo (eds.): Canova, Hayez, Cicognara. L’ultima gloria di Venezia, Venezia 2017, pp. 156-170.

Fernando Mazzocca: “Hayez vero erede di Canova crea il Romanticismo e abbandona Venezia per Milano”, in: Fernando Mazzocca, Paola Marini, Roberto de Feo (eds.): Canova, Hayez, Cicognara. L’ultima gloria di Venezia, Venezia 2017, pp. 278-281.

Omar Cucciniello: “Il monumento a Giuseppe Longhi nel Palazzo di Brera: un confronto tra Pompeo Marchesi e Thorvaldsen”, in: Stefano Grandesso, Francesco Leone (eds.): Dall’ideale classico al Novecento. Scritti per Fernando Mazzocca, Milano 2018, pp. 79-85.

Giuseppina Di Gangi: “Le sale napoleoniche e la galleria dei veneti”, in: Emanuela Daffra, Marco Tanzi (eds.): Sesto Dialogo. Attorno agli Amori. Camillo Boccaccino sacro e profano, Milano 2018, pp. 82-93.

Francesco Leone: “Sopravvivenze classiche. La resistenza contro il Romanticismo”, in: Fernando Mazzocca (ed.): Romanticismo, Milano 2018, pp. 41-43.

Andrea Di Lorenzo: “Vicende collezionistiche e fortuna critica della Madonna Litta fra XV e XIX, prima della partenza per la Russia”, in: Andrea Di Lorenzo, Pietro C. Marani (eds.), Leonardo e la Madonna Litta, Milano 2019, pp. 49-57.

Fernando Mazzocca: “Canova e Thorvaldsen a Milano e in Lombardia”, in: Stefano Grandesso, Fernando Mazzocca (eds.): Canova Thorvaldsen. La nascita della scultura moderna, Milano 2019, pp. 53-59.

Claudio Salsi: “Raffaello, persistenza del mito: dalle botteghe dei Maiolicari al Neoclassicismo”, in: Claudio Salsi (ed.): Giuseppe Bossi e Raffaello al Castello Sforzesco di Milano, Milano 2020, pp. 17-31.

Works referred to

Last updated 02.06.2023