Anima Beata

- Kira Kofoed, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2016

- Translation by Andrew D. Jackson, Karen Jelved

Among Thorvaldsen’s many hundred works, there are two rather modest reliefs about which we have so far known relatively little.

- Woman Ascending to Heaven, above the Genius of Death, A625

- Monument to Stanislaus Chaudoir’s Wife, A624

Through new sources, among other things, this article gets closer to the reliefs, the person portrayed, and their common motifs and rediscovers the original marble version in the Ukraine to the benefit of Thorvaldsen scholars.

The first part deals with the commission itself, its progress, and the after-life of the relief, while the second part studies the motif in connection with other works by Thorvaldsen and in the light of Christian and Antique mythology.

- 1. A hitherto unnoticed title

- 2. A brief description of the genesis of the two reliefs

- 3. The internal chronology and after-life of the two reliefs

- 4. A description of the internal similarities and differences of the reliefs

- 5. The genius of death

- 6. The raised arms as a postural attitude in Thorvaldsen’s art.

- 7. The motif in context

- 8. The reliefs as mentioned in contemporary sources

- 9. References

A hitherto unnoticed title

On a list of works written by Thorvaldsen himself, a work entitled Anima Beata is entered for the year 1814.

This is Latin – and Italian – for blessed soul, i.e. in a Christian context an image of the soul of a good, devout person who is ensured eternal life in Heaven.

No relief with such a title is known to Thorvaldsen scholars, but at least two reliefs from Thorvaldsen’s hand could correspond to the motif and thus give us a clue to the work in question:

- Woman Ascending to Heaven, above the Genius of Death, A625

- Monument to Stanislaus Chaudoir’s Wife, A624

That this is the relevant group of motifs is confirmed by a contemporary reproduction on a small scale entitled L’Anima beata che sale al Cielo. The reproduction shows the variant Woman Ascending to Heaven, above the Genius of Death, A625, and will be dealt with below.

|

|

| Woman Ascending to Heaven, above the Genius of Death, A625, also called Anima Beata. | Monument to Stanislaus Chaudoir’s Wife, A624, also called Anima Beata. |

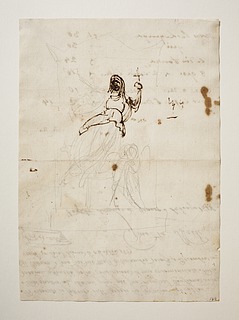

Also a, most probably, preparatory sketch is connected with the group of motifs: Monument to Stanislaus Chaudoir’s Wife, C168r.

|

Monument to Stanislaus Chaudoir’s Wife, C168r. The drawing is executed first in lead and then inked in around the woman’s head, her left arm with a cross, and her upper body. In addition to the figures, the drawing also includes the full architectonic outline of the monument itself (a stele topped with an acroterion). Within the physical frames of the monument, another stele has been indicated as part of the motif of the relief under and behind the woman. This stele, which must be regarded as an image of the grave of the deceased, has not been transferred to the bas-reliefs, whose background is completely empty. |

A brief description of the genesis of the two reliefs

The date of 1814, however, cannot be correct because it was not until the summer of 1818 that Thorvaldsen was contacted by the Polish-Russian archeologist, numismatist, etc. Stanislaus de Chaudoir, who wanted to commission a relief for a monument to his late wife: nach verabredeter Art [i.e. of the type agreed upon]. The wife’s name and further identity have not previously been known to Thorvaldsen scholars, but thanks to recently discovered sources, it has now become possible to give her back her name. She is the Austrian-born Aloisia de Chaudoir, née d’Erggelet, who died quite young after only three or four years of marriage to Stanislaus de Chaudoir.

The first known written evidence regarding the contract is dated 12.6.1818, including a brief description of the commission and a confirmation of Chaudoir’s payment to Thorvaldsen of 200 of the agreed total of 1,000 Roman scudi. The first (known) drawing of the monument, C168r, is found on the back of a receipt, dated Rome 24.12.1817, so the sketch cannot have been earlier.

On 17.9.1820, Chaudoir wrote to Thorvaldsen, asking him whether he had had time to think about the relief – in spite of his journey to Denmark and many new, important commissions. Chaudoir intimated that he would pay another 400 (of the total of 1,000) scudi to Thorvaldsen. On the same occasion, he asked to have a portrait of his late wife returned to him if Thorvaldsen no longer had need of it. From this, it is possible to conclude that Chaudoir wanted the relief to have a certain likeness. The portrait in question may have been one painted by the Austrian painter Johann Baptist von Lampi the Younger (1775-1837), who painted her portrait as a counterpart to a similar portrait of her husband.

The relief was executed in marble, cf. workshop accounts dated October 1819 – June 1821 and letters dated 3.12.1819 and 16.1.1820 from the sculptors Hermann Ernst Freund and Pietro Tenerani, but until today Thorvaldsen scholars have not known the location of the marble version. Dubman’s article, op. cit., however, reveals that the relief, in spite of a turbulent existence, is now at the Zhytomir Regional Museum in the Ukraine.

The relief was originally, but on an unknown date, placed on the family tomb of de Chaudoir’s now demolished estate at Ivnytsya in the Ukraine. After the grandson Ivan de Chaudoir (1859-1919) sold the estate in 1907, the family tomb, including Thorvaldsen’s relief, was transferred to the new Protestant cemetery in Zhytomyr. Here it was vandalized in connection with the burial of the Bolshevik Vasily Nazarovich Bozhenko (1871-1919) in August 1919, but the relief was saved and later hidden from the Nazis during World War II in the crypt under the Holy Transfiguration Cathedral (Preobrasjenski Sonor) in Zhytomyr. In 1918, all de Chaudoir’s collections were donated to the Zhytomir Regional Museum. The drawing C168r and the relief Woman Ascending to Heaven, above the Genius of Death, A625, is probably, but not necessarily, to be seen as a sketch for the final monument.

The internal chronology and after-life of the two reliefs

The two variants are rarely mentioned in the Thorvaldsen literature, and most often it is the version, A624, with the hovering woman in profile and the genius looking upwards, that is mentioned and depicted. Even though the location of the finished marble relief was not known previously, there seemed to be general agreement that it was precisely the version with the woman in profile that had been the model for the marble version. This has been confirmed by the re-discovery of the relief.

According to Thiele II, p. 382, the completed relief in marble was shipped from Rome to Poland in 1828. Thiele’s source for this is not known. However, it seems certain that the monument was shipped not later than 1829, when it is mentioned as having been shipped in a letter dated 8.1.1829.

It has previously been assumed that the woman seen frontally, A 625, like the drawing C168r, was the model for the final monument with the woman seen in profile, A624. This is not necessarily untrue but a contemporary reproduction shows that the first (?) relief also had an independent life as a general representation of the good soul’s flight to Heaven: The family firm of Paoletti, which in Thorvaldsen’s contemporary Rome sold popular motifs from the art world in the form of easily distributable gems and ornaments, sold precisely the frontal variant of the motif, A625, as L’Anima beata che sale al Cielo [the blessed soul ascending to Heaven].

It is not known with certainty whether this variant had already been executed in connection with de Chaudoir’s commission and thus could be the “type agreed upon” referred to in the text. An argument against such an interpretation is probably the date of the drawing with the same motif, C168r, which was executed on the back of the above-mentioned receipt dated 24.12.1817. In that case, A625 must have been executed between Christmas 1817 and the summer of 1818, when de Chaudoir contacted Thorvaldsen.

A description of the internal similarities and differences of the reliefs

In both cases, the plaster reliefs show a centrally placed, hovering woman with a Christian, Latin cross in one hand. Below to the right of the woman, there is a genius of death with a torch pointing downwards as a classical, antique image of death. In one version, A625, the woman’s torso is shown frontally, and her right arm is stretched upwards, while the woman in the other version, A624, has crossed her hands in front of her, close to her chest, and she is shown entirely in profile. In both variants, the women are fully draped, particularly in the version in profile, where the arms are also covered and the drapery generally closer to the body – with the exception of the ends of the scarf streaming behind her.

Thus the representation of the female figure changes roughly from an open, extrovert figure to a closed, introvert figure. The above-mentioned drawing, C168r, corresponds largely to the frontal variant of the relief as far as the position of the female figure is concerned, which might confirm the thesis that the drawing is the first sketch, the frontal relief the first sculptural sketch, and the relief in profile the final model used for the marble monument.

|

|

| Woman Ascending to Heaven, above the Genius of Death, A625, also called Anima Beata. | Monument to Stanislaus Chaudoir’s Wife, A624, also called Anima Beata. |

The genius of death

The way in which the genius of death is represented is also different from one relief to the other, but in a way almost opposite to the woman’s change from an open to a closed figure. In the frontal version, A625, the boy is shown slumbering and introverted with his head bent down and resting on the down-turned torch. Contrary to the female figure, he is seen almost completely in profile and rests fully only on one leg in a variation of the classical contrapposto pose. In the version in profile, A624, the boy is awake and is actively looking up towards the figure ascending to Heaven, while his legs assume a more secure stride stand position although there is still a slight contrapposto with the weight more on one foot than on the other. As if to maintain the contrast to the woman, he is shown more frontally. The poppy capsules (an antique symbol of sleep and death) seen in the boy’s hand in the frontal relief have disappeared in the relief in profile. Thus the representation of the genius of death also changes in relation to the female figure from an introverted and passive expression to a more active and extroverted one.

Thus, there has been a considerable revision of the motif – from an antique and classical representation of the genius of death as a resting, grieving, and almost passive figure to a more alert and lively version that perceives his surroundings in a much more active and not least hopeful manner. The secure position of the genius’ legs seems to reflect its certainty in the belief that the devout woman’s soul is doing well – she is on the way. The grief has gone, and the religious expectation and optimism are gathered in the basic Christian idea of hope. The hope is stressed by the fact that no mourners are shown in the relief, and there are no earthly elements to disturb the positive interpretation.

There are examples of a few more “active” genii of death in Thorvaldsen’s art. In his Monument to two Poninski Children, A616, the genius of death also plays a more lively role, i.e. as a guide on the journey from this world to the next. The two worlds are here oriented horizontally, and not vertically as in the Anima Beata reliefs. The deceased woman in the Poninski relief, however, points towards Heaven in order to illustrate the Christian context.

Monument to the two Poninski Children, A616, where the genius of death functions as a horizontally oriented guide.

In the preliminary sketches for the same relief, the genius is seen to play an increasingly active role, and the two worlds are not realized in the form of two hemispheres until the final version. In this case also, the work was a commission, i.e. the pictorial composition was decided by the person who commissioned the work, which explains the peculiarity of the relief in relation to Thorvaldsen’s other works.

Monument to Jane Lawly, A623, where antique heathen attributes have been replaced by Christian ones.

Another work by Thorvaldsen, Monument to Jane Lawly, A623, shows two genii who also distance themselves more from the antique heathen context than is usual in Thorvaldsen. In the relief, he has completely omitted the extinguished torch as a symbol of death. Instead, the medieval, and thus in a European context Christian, hourglass is shown to the dying, kneeling woman who is praying hopefully to God, while the other genius records her deeds on a parchment scroll – a role Thorvaldsen usually reserved for the Greek goddess of justice and revenge, Nemesis, cf. e.g. Monument to Auguste Böhmer, A700, or Monument to Johann Philipp Bethmann-Holweg, A615,3.

A similar use of the hourglass and the recording of the deeds of the deceased is seen in the two genii or angels that flank Thorvaldsen’s monument to Pope Pius VII, cf. A146, A147 and A142.

The heathen attributes and figures clearly have nothing to do with the Head of the Catholic Church.

|

|

| Angel, A146, in the typical role of Nemesis as a recorder of deeds. | Angel, A147, with hourglass. |

The raised arms as a postural attitude in Thorvaldsen’s art.

The woman’s raised arms also play an important role in the change in the motif and its statement. The postural motif with one or more raised arms is known in Thorvaldsen’s art primarily as an expression of intense grief, see e.g.

- Monument to Jacqueline Schubart, A704

- Sketch for the still unidentified monument, C188a

- Monument to Ana Maria Porro Serbelloni, A619

- Monument to the two Poninski Children, A617

- Monument to Johann Philipp Bethmann-Holweg, A615,2.

- Monument to Jozefa Borkowska, A621

In all these cases, the raised arms are reserved for the bereaved, i.e. the impotent and expressive mourners.

|

|

| Monument to Jacqueline Schubart, A704 | Monument to Ana Maria Porro Serbelloni, A619 |

|

|

| Monument to Johann Philipp Bethmann-Holwegg, A615,2 | Monument to Jozefa Borkowska, A621 |

However, the position is also in a few cases seen as an expression of prayer, as in Children Praying, for the Monument to Artur Potocki, A628, and in two later representations, i.e. Thorvaldsen’s representation of Denmark, A550, where the posture of the personification of Denmark rather indicates the invocation of God to bless the King (as the text on the medallion states), and the small Genius of Religion, A 545, from 1838, where the raised arms also indicate prayer.

|

|

| Children Praying, for the Monument to Artur Potocki, A628 | Denmark, A550 |

In the Anima Beata relief with the frontally oriented woman, A625, the raised arms seem to unite the two meanings – the posture expresses acknowledged sadness but not intense grief and can also be interpreted as an invocation of God to be mercifully received in Heaven, i.e. a greeting of combined leave-taking, grief, and invocation. This representation is unique in Thorvaldsen’s art but fits nicely into the broader art history of the period, as will be seen below.

h3. The motif in context

One of the great pioneers of Neoclassicism was the British draughtsman and sculptor John Flaxman, whose former workshop Thorvaldsen took over after his arrival in Rome in 1797. Flaxman had left Rome in 1794, so the two sculptors did not know each other personally, but Thorvaldsen owned several engravings of Flaxman’s drawings, and there is no reason to doubt that also Thorvaldsen was influenced by his simple idiom and received news of Flaxman’s works also after the latter had left Rome.

The art historian H.W. Janson, op. cit., mentions the similarity between Thorvaldsen’s Monument to Stanislaus Chaudoir’s Wife and Flaxman’s Monument to Agnes Cromwell, 1797-1800, in Chichester Cathedral in Sussex. Flaxman’s relief shows the deceased (or her soul) on her way to Heaven accompanied by three genii or angels – two who lift Agnes Cromwell upwards and one who hovers protectively above the other three figures showing the way. The inscription above the monument reads: Come thou blessed, i.e. with a meaning identical to Anima Beata.

As Thorvaldsen never visited England, he did not see the work in situ, but he may well have heard about it and/or seen reproductions of it. However, there is no documentation either for this or for Chaudoir’s more detailed requests regarding the design of the monument. In the first receipt of payment, as described above, the only specification was that the work should be executed according to “the type agreed upon”. Nor are more specific details mentioned in subsequent letters from Chaudoir to Thorvaldsen.

Thus, the expectations to the motifs of the monument that may have been expressed orally in connection with the commission in the summer of 1818 can probably be summarized in the title that Thorvaldsen later wrote on his list: Anima Beata, a blessed soul. As has become clear, it was a new theme in Thorvaldsen’s art but extremely popular in an English context from the end of the 1700s to the end of the 1800s. It was precisely the break with the antique, heathen style with urns, torches pointing downwards, withered flowers, and broken columns that parts of British society wanted to eliminate. Instead, they wanted to promote a “pure” Christian iconography – with the cross, the hourglass, and the Christian virtues of faith, hope, and charity as the most important elements. The powerless grief over the earthly loss of a loved one depicted in the majority of Thorvaldsen’s reliefs, as exemplified above, was to be replaced by the confident Christian hope of resurrection and eternal life in the Kingdom of God. This change corresponds completely to the vertically oriented solution in Thorvaldsen’s relief A624. Faith and optimism flourish. The downturned torch is still there, but the poppy capsules, the heathen symbol of sleep and death, have gone, and the sadly slumbering genius now confidently follows the blessed spirit’s flight to Heaven. All lines, all eyes are directed towards Heaven, and faith triumphs in the form of the cross in the woman’s hand.

In the painting with the same title, Beata Anima, from 1640-1642, by the Italian baroque painter Guido Reni, the central figure is a young male winged genius. According to Reni’s own notes, he called the motif Divine Love. Here he plays on the merger of the representation of Cupid, the antique god of love, and the figure of the genius both as an antique protector of people and ideas and as a messenger between the human and the divine. The introduction of this ambiguity to the interpretation of Thorvaldsen’s representation of the genius of heathen death in a specifically Christian universe in the Monument to Stanislaus Chaudoir’s wife unites the three Christian virtues – faith, hope, and charity.

The reliefs as mentioned in contemporary sources

| Title / designation | Kilde | Variant |

| Anima Beata | Not before 1818 | Unknown which of the two variants A624 or A625 |

| Anima e Genio | October 1819 – June 1821 | Probably A624 |

| Anima e Genio | October 1819 – June 1821 | Probably A624 |

| det Monument vorpaa der er den svævende Figur [the monument on which there is the hovering figure] | 3.12.1819 | Probably A624 |

| il bassorilievo detto l’Anima Beata | 16.1.1820 | Probably A624 |

| det Monument vorpaa der er den svævende Figur [the monument on which there is the hovering figure] | 19.8.1820 | Probably A624 |

| Dødens Genius, staaende med nedvendt Fakkel; Troen, en qvindelig Figur, den Afdødes Billede, svæver mod Himlen. [The genius of death, standing with downturned torch; faith, a female figure, the image of the deceased, ascending towards Heaven] | Summer 1820 | Probably A624 |

| il Basso rilievo del’anima and Basorilievo del anima | Probably 1820’s | Probably A624 |

| Basrelieffet til Baronesse Chandry’s Gravmonument. (En qvindelig Figur, som svæver til Himlen med Korset) og Gravmælet over Barosse Chandry [The bas-relief of the monument to Baroness Chandry. (A female figure ascending towards Heaven with the cross) and the monument to Baroness Chandry] | 28.6.1830 | A624 |

| Baronesse Chandrys Gravmonument og Baronesse Chandry [The monument to Baroness Chandry and Baroness Chandry] | September 1830 | A624 |

| Grabmal der Baronesse Chandry | 1837 | A624 |

| Gravminde over Baronesse Chandry [Monument to Baroness Chandry] | 19.11.1838 | A624 |

| den Afdøde under Billedet af Troen, som, holdende Korset i de foldede Hænder foran sit Bryst, hæver sig op over Dødens Genius imod Himlen. [the deceased under the image of Faith, holding the cross in her folded hands in front of her chest, ascending towards Heaven above the genius of death] | Thiele 1832, part 2, p. 43 | A624 |

| L’Anima che vola al cielo | Missirini, 1832, op. cit. | A624 |

| L’Anima beata che sale al Cielo | Paoletti, 1821-1834, cf. Stefanelli, op. cit. | A625 |

| Dödens Genius seende mod Himlen. (Af Gravmælet over baronesse Chandry.) [The genius of death looking towards Heaven (from the monument to Baroness Chandry.)] | 5.10.1849 | Part of A624 |

References

- H.W. Janson: Nineteenth-Century Sculpture, London 1985, p. 73.

- Melchiorre Missirini: Intera collezione di tutte le opere inventate e scolpite dal Cav. Alberto Thorwaldsen, Rom 1831-1832, vol I, nr. 51. Identisk med THM A624.

- P. Basilewsky: ‘Baron Maximilien de Chaudoir (1816-1881)’, in: The Coleopterists Bulletin, vol. 36, No. 3, ‘Baron Maximilien de Chaudoir Memorial Issue, Part 1’ (Sep., 1982),” p. 462-474, The Coleopterists Society.

- Boris Dubman: ‘Geschichte Shitomirs. Der Schatz der Barone Chaudoir’, in: Shitomirer Online-Journal vom 12.7.2012.

- Max Dvorak (edit.): Österreichische Kunst-Topographie, Bd. XVI: Die Kunstsammlungen der Stadt Salzburg, Wien 1919, p. 11-12.

- Nicholas Penny: ‘Symbol and Style in English Nineteenth Century Sepulcral Sculpture’, in: Horst W. Janson (ed.): La scultura del XIX secolo, Bologna 1984, p. 189-198.

- Olena Shapiro: ‘The European Dimension. How a family with intellectual interests gathered a collection of paintings by world-renowned artists for their estate in the town of Ivnytsia, Zhytomyr oblast’, in: The Day, 5.11.2014.

- Lucia Pirzio Biroli Stefanelli: La collezione Paoletti. Seconda parte: Stampi in vetro per impronte di intagli e cammei, Rom 2016, vol. 2, p. 207, kat.nr. 77, inv.nr. MR 27614. Identisk med THM A625.

- Thiele 1832, 2. del, p. 43. Identisk med THM A624.

- Thiele II, p. 382.

- Korrespondance med Lidiia Dakhnenko, Zhytomir Regional Museum, december 2016, Thorvaldsens Museums journal 0242237.

- Korrespondance med Sergiy Matyushenko, Den danske ambassade i Ukraine, december 2016, Thorvaldsens Museums journal 0001070.

Works referred to

Last updated 15.01.2021