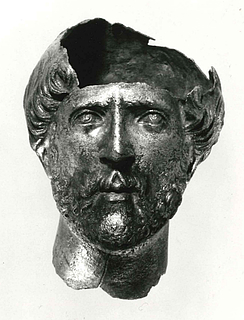

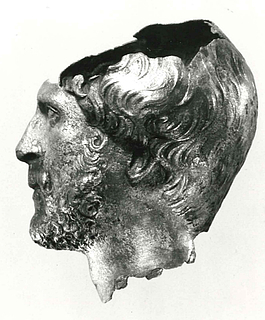

Fig. 1. Silver portrait, full face. Height: 6.4 cm. C. 120 A.D. H1951.

This is a re-publication of the article:

Niels Hannestad: ‘Thorvaldsen’s Small Silver Head – A Ruined Tondo Portrait’, in: Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum (Communications from the Thorvaldsens Museum) 1982, p. 27-65.

For a presentation of the article in its original appearance in Danish, please see this facsimile scan. For a presentation of the article in its original appearance in English, please see this facsimile scan.

Among Thorvaldsen’s antiques there is a small portrait head in silver (figs. 1-6). In his catalogue Ludvig Müller writes with laconic appositeness that it is “of excellent art”I. It is generally known as ‘Antoninus Pius’, an identification to which we shall return.

Thorvaldsen left no details as to how he built up his collection of works of art and antiques. As was not unusual among practising artists he bought up antiques without bothering too much about the petty details of establishing their provenanceII. Perhaps the silver head was acquired one early Sunday morning on the Piazza Montanara, which was then situated by the Marcellus theatreIII. Here peasants and farmers came with the objects they had unearthed during the course of the week. As at the modern flea market in the Porta Portese, what they had to offer consisted for the most part of small objects that could be concealed in a pocket. Thorvaldsen is said to have been present every time, but in his extensive activity as a buyer he also made use of all other existing channels to increase his collection. Week after week during his stay in Rome new additions were made, and it is, at any rate, probable that the head came to light in Rome itself or in its immediate surroundings.

Fig. 1. Silver portrait, full face. Height: 6.4 cm. C. 120 A.D. H1951.

The silver head itself is very small. In its present condition its maximum height is 6.4 cm., while the face itself measures 3.65 cm. It is not, as was earlier assumed, worked in repoussé, but cast by the cire perdue method, after which such external details as the irises and pupils were executed by engraving. There is still a remnant of the core in the tip of the nose. As is characteristic of this kind of Roman work in a precious metal, the amount of material used is modest. It weighs 39 gr. and is about 1 mm. thick, a contributory factor in the loss of most of the crown, the hair over the forehead and part of the left temple. There are two small holes on the right side of the head, one at the temple, where hair and beard meet, and one at the base of one of the forehead curls. The neck is delimited at the bottom by an irregular break, which roughly follows the hairline at the back.

The metal is rather corroded, and in several places, most markedly on the tip of the nose, flakes of the original surface have peeled off. The condition of the piece bears unmistakable witness to it having been found in the earth.

The portrait represents a man of about 40, with regular not yet sharp features and well-groomed hair and beard. The face is oval, the nose narrow and straight apart from a very slight break. The mouth with its short lips seems to lack firmness, and together with the knitted brows it gives the person a faintly worried, watchful appearance. The preserved part of the neck shows that in relation to the missing shoulders the head was turned a little to the right and at the same time somewhat raised as if the eyes were looking up.

The hair is thick and vigorous, combed forward so that it covers the head like a cap. It is slightly wavy and ends in a series of individually worked curls that circle the head like a wreath. The hair half covers the ears, and the line of the break shows how far down it conceals the forehead. Through the short, tightly curled beard we sense the presence of a rather pointed chin.

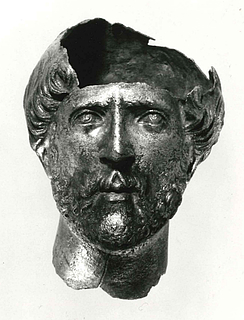

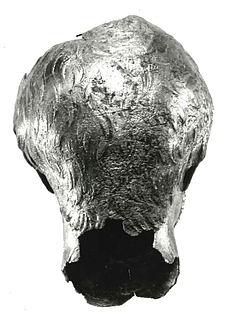

Fig. 2. The silver portrait fig. 1. Rear view.

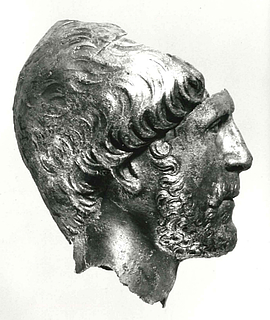

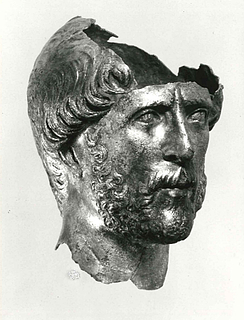

Fig. 3. The silver portrait fig. 1. Profile facing right.

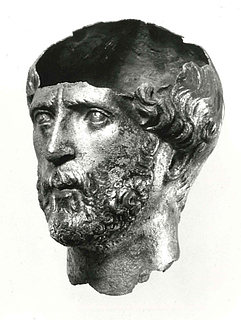

Fig. 4. The silver portrait fig. 1. Profile facing left.

H1951.

It is evident that the engraving is much more casual at the back of the head, where the individual locks are only roughly indicated (figs. 2-4). It appears that this part of the head was not intended to be visible. This together with the angle of the neck, which shows that the eyes were looking upwards, makes it fairly certain that the head was broken off a bust, which had been inserted into a section of a sphere. This is, then, a tondo portrait, and it can be assumed that the bust was originally mounted in a shallow silver dish or phiale as in fig. 7, which shows a portrait phiale, one of the best known pieces in the Boscoreale treasure, found near Pompeii in 1895 and now, like the greater part of the treasure, in the Louvre, ParisIV. The grim-looking gentleman on the Boscoreale phiale had a counterpart — presumably his wife — in a female bust, which has ended up in London, and of which the dish has been lostV. Several such busts of gods and humans have been preserved from Imperial times. As a rule they are of a very high technical and artistic quality, and the silver is often decorated with partial gildingVI.

Silver bowl with Tondo Portrait. From Boscoreale at Pompeii. Diameter: 24 cm. 1. Century AD. Louvre, Paris.

Neither form nor material, to which we shall also return, give any a priori help towards an identification, except for the fact that the man represented must have been a member of the upper class. As mentioned above, the head goes by the name of Antoninus Pius, the Roman Emperor (138-161 A.D.). The name was attributed to it in 1940 by Frederik Poulsen in a review of the German scholar Max Wegner’s great work on the portraits of the Antonine dynasty, Die Herrscherbildmsse in antoninischer Zeit.

Scholars working with portraits have perhaps not always been overly cautious in their attribution of names to the pieces with which they have been concerned, and museums have always been anxious to possess well-known faces and to fill in gaps in their collections. Furthermore, it is generally more interesting to be occupied with the physiognomy of a well-known historical personage than with that of some unknown.

The imperial portraits are well established up to the close of the Severan period. The various portrait types of the successive emperors have been firmly defined, also in relation to each other, and two generations into the third century we are still familiar with the appearance of each individual ruler. Numismatic evidence provides the basis for the identification of individual images as well as the establishment of the iconographic typologies.

Among the portraits of the Roman emperors, that of Antoninus Pius is one of the most stable. We know no portraits of him before he became Emperor at the age of 51 on Hadrian’s death in 138 A.D. With variations and stylistic changes the portraits of the following 23 years derive from one and the same basic type, evidently created on the occasion of his accession to the throneVII. An examination of the coin material confirms that the same type of portrait dominates the entire periodVIII.

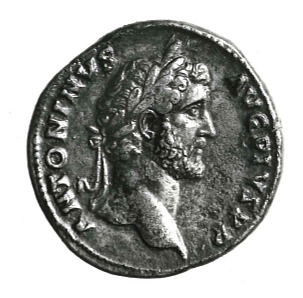

In Thorvaldsen’s coin collection there are a number of Antoninus Pius coins, among them a beautiful sesterce (figs. 8a-b) with a laurel-wreathed portrait of the Emperor on its face. The reverse side, which depicts the twins, Romulus and Remus, being suckled by the wolf, is one of a series representing the foundation of Rome, which was struck to commemorate the 900th anniversary of the city in 148 A.D.IX

Figs. 8a-b. Sesterce of Antoninus Pius. Obv. and rev. Struck on the occasion of the 900th anniversary of the founding of Rome, A.D. 148. Bronze. K3154.

When dealing with conjectured imperial portraits in precious metal, especially miniatures, scholars have often tended to be somewhat less stringent than normal as regards likenessX. This may not be unreasonable with respect to finds made on the borders of the Roman Empire in the so-called limes-area, where the army often had imperial portraits made by local craftsmen after models brought from Rome. Thorvaldsen’s silver head must, however, derive from a metropolitan Roman milieu and is extremely competently, not to say splendidly, executed. If it is to be accepted as the likeness of an emperor, we must be able to demand an absolute feature-by-feature concurrence with established types.

Let us, then, make a fresh start with the coin portrait (fig. 8a), which, despite the laurel wreath, presents all characteristic features. In comparing it with the profile picture in fig. 3, we note, first of all, a radical difference in hair style. The Emperor’s beard is somewhat fuller, while the hair on his head is far wavier and ends at the forehead and temples in great unruly involuted curls. Nevertheless, the hair does not come as far forward as on the silver head. Antoninus’s ears are not covered, and it is clear that he has receding temples, an impression that is further confirmed by the characteristic sheerness of his high forehead. Despite the abundance of hair it can be seen that the back of his head is flat, while our silver head presents a beautifully curved cranium. The coin portrait also reveals that Antoninus Pius has remarkably straight eyebrows jutting out above the eyes, while those of the silver head are finely arched. The coins do not, however, show, that as opposed to the silver head the Emperor has a broad straight mouth with thin, tightly pressed lips. Similarly, there is a suggestion of a broad, rectangular face, very different from the oval of the silver head. A slightly worried expression is all that the two men have in common.

With the rejection of its traditional identification, the dating of the silver head becomes an open question. In order to arrive at a new dating we must return to the question of imperial portraits, on which the dating of private portraits is generally based, even though it is far from uncommon for the two groups to follow different lines. Especially in the 2nd century there is generally a greater degree of realism to be met in private portraits than in imperial portraitsXI. Certain restraints adhere to the portrait of an emperor. It may be idealized or starkly, even grossly veristic, but first and foremost it is a political manifestation. More than being a representation of physiognomical characteristics, it is an image of the Emperor as he wished to be perceived by his subjectsXII. Once adopted, a role was generally maintained throughout an entire reign, and only a minority actually saw the Emperor in the flesh. In several instances we know positively that an emperor’s appearance differed from the way in which he chose to be representedXIII. In both type and style private portraits enjoyed greater freedom. During the Roman Empire the development of style was a far from linear process. According to taste and purpose both patron and artist could choose freely from within a large range of stylistic and iconographical models. It is, therefore, a constant source of difficulty as regards dating that widely different stylistic features both appear side by side and succeed one anotherXIV.

It is, then, for lack of a better principle that private portraits are dated on the basis of imperial portraits, and it should be realised that very rarely will there be conclusive evidence in the form of a dated inscription or the like.

The hairstyle of the silver head reflects the fashion that predominated during Trajan’s reign: an abundant growth of hair combed forward from the crown of the head to cover it like a cap. Towards the end of Trajan’s reign and under Hadrian this rigid style becomes increasingly vital. The hair becomes wavy, and the curls which form a wreath around the head are raised. These are stages on the way towards the completely untrimmed manes of the High Antonine period that Marcus Aurelius, among others, displayed.

Hadrian was the first emperor to wear a beard, and there are good grounds for seeing this as a symbol of the Greek Renaissance, of which this emperor has come to be regarded as its representative. Since the days of the Republic only soldiers and slaves had worn beards, but shortly after 100 A.D. educated and, not least, hellenophile Romans began to acquire beards. The attitude of contemporary society towards the new fashion was not without irony as shown in an epigram attributed to Lucian (Epigr. 45 – transl. W.R. Paton):

If you think that to grow a beard is to acquire wisdom,

a goat with a fine beard is at once a complete Plato.

During Hadrian’s reign the fashion became firmly established and continued right up to Emperor Constantine the Great.

On Trajan’s Column, which was dedicated in 113 A.D., with its reliefs illustrating Trajan’s victories in Dacia, several of the most senior officers wear beards and a hairstyle like that of the silver head. Others have hair and beards like Hadrian while yet others are clean-shaven with hairstyles corresponding to those of the Flavian emperors or Trajan. If we base our dating on the imperial portraits, the hair and beard styles with which Trajan’s staff officers are represented span almost one and a half generationsXV.

As Thorvaldsen’s head is of metal, we are unable to use a criterion that is applicable to marble sculptures. Around 130 A.D. workshops in Rome began to render the iris and the pupil plastically, whereas they had previously been indicated by painting. At that time this change can hardly have seemed so radical as it does at the present day, when there are seldom any traces of colour left on marble sculptures. In metal work, however, paint could not be used, and instead the iris and pupil were indicated by inlay of other material or by engraving, as in the case of the silver head (figs. 1, 5-6) and the man on the Boscoreale phiale (fig. 7). Because of this technical detail a superficial examination of the portrait may give an erroneous impression that it is later than it actually is.

If we are to attempt a dating of our object, we must place it in the late-Trajanic/early-Hadrianic period, or, in the terminology of Carbon-14, at 118 A.D. ± 15 years.

Fig. 5. The silver portrait fig. 1. Three-quarter profile facing right.

Fig. 6. The silver portrait fig. 1. Three-quarter profile facing left.

H1951

There is, then, no exact parallel to its hair and beard fashion in the imperial portraits. On the other hand, there are several private portraits which are close to the silver head in style and type, but none reveal so much similarity of feature as to suggest an identity of subject.

Who, in that case, is our man? The beard indicates a person who was fashion-conscious though not necessarily as much of a hellenophile as Hadrian. The wrinkles on the forehead can also give us some general information: the thought-laden expression is intended to convey the social importance of the subject. There was to be no doubt that here was a man who bore a heavy responsibility on his shoulders. This grave, often brusque expression is frequently to be found in the many portraits of officers of the time as an intimation of the way in which this class saw itself. However, this pensive appearance is also regularly encountered among members of the upper class who had themselves represented in the guise of a Greek philosopher.

Roman society, not least in the middle of the Imperial period, was characterized, almost paradoxically, by great social mobility at the same time as it was pervaded by an unusually high degree of class consciousness, and this is particularly expressed in the way in which its members had themselves portrayed. Clothing, attributes, facial expression, posture, etc., — all these factors carried a clear symbolic significance.

The confident acknowledgement of social status in no way blurred the individuality of the person represented. On the contrary, there was an unbroken tradition of realistic features in private portraits which continued until the middle of the 3rd century, when the realistic or, rather, veristic Roman portrait — both imperial and private — disappeared to be replaced by a mask. The causes of this development are many and, in part, obscure, but an important role was undoubtedly played by structural changes in society which became increasingly manifest during the 3rd century. The great culture-bearing middle class, which was bound up with the urban culture of antiquity, disappeared, and the feudal society of the medieval world emerged, characterized by a small upper class and a lower class, virtually without legal rights, that comprised the rest of the population. In comparison with earlier periods the status of the upper class was given and almost unobtainable for others.

As the bust belonging to the silver head has not been preserved, it is impossible to determine whether the subject was represented as an officer with cuirass or general’s cloak, as a Greek philosopher with himation over his left shoulder (as in fig. 11), as a citizen in a toga or heroically nude like the man on the Boscoreale phiale (fig. 7). Members of the Roman upper class could have themselves represented in these or other roles according to fancy. In real life they also had a number of roles at their disposal. Senior officers, like those we meet around the Emperor on Trajan’s Column, were also senators and administrators. In addition, the individual officer might have philosophic interests, might wish to be represented in heroic nudity or as a hunter.

It is hardly possible to get any closer towards an identification. The man portrayed in Thorvaldsen’s silver head was undoubtedly a member of the real upper class, in all likelihood one of the 600 members of the Senate, although the members of the numerically far larger and economically important equestrian order cannot be excluded from consideration.

In large form the tondo portrait, or as the Romans themselves termed it, clipeata imago (the shield portrait), is to be found representing members of ruling dynasties, private persons or gods, executed in metal, stone or paint. Such tondi often formed part of an architectonic context, and in many cases they were designed to be hung on walls, etc.

What was originally a Greek motifXVI was taken over and developed by the Roman world. The great Republican families, that is, those that had ancestral portraits, placed such likenesses in the atrium of the house, and there is evidence from the latter part of the Republican period to show that public buildings were decorated with such tondi. Thus, the Elder Pliny wrote in his Natural History (N.H. 35, 12 — transl. H. Rackham): “But the first person to institute the custom of privately dedicating the shields with portraits in a temple or public place, I find, was Appius Claudius, the consul, with Publius Servilius in the 259th year of the city (79 B.C.XVII). He set up his ancestors in the Temple of Bellona and desired them to be in full view on an elevated spot, and the inscriptions stating their honours to be read. This is a seemly device, especially if miniature likenesses of a swarm of children at the sides display a sort of brood of nestlings; shields of this description everybody views with pleasure and approval.”

In the house of the Senate, the Curia, tondo portraits of emperors were hung. It is known that there was one of Trajan in silver and one of Claudius Gothicus (268- 70) in gold. Domitian had a golden tondo portrait hung, but it was immediately taken down when he was murdered and his memory condemned in 96 A.D. We can form an impression of what these portraits were like from the relatively numerous stone tondi that have been preserved and from murals in which they form part of the compositionXVIII. Only few metal examples have been preserved, and nearly all those executed in wood have disappeared.

In miniature, in approximately the same size and shape as the Boscoreale phiale (fig. 7) and the dish that originally surrounded Thorvaldsen’s silver head, imperial portraits were used in a military context. Such metal tondi with busts of members of the imperial family formed part of the decoration of the standard poles borne by military units as their regimental colours. The imperial bust also formed the central ornament on the so-called phalerae, round emblems, normally about half as large, which hung on the horse’s breast as part of its harness. Phalerae were also used as a man’s personal decoration or as a badge of rank. Such ornaments correspond more or less to what we should term medallionsXIX. Even in so small a format as the face of a coin the imperial portrait was sacred. To mock it or damage it was, potentially, a capital offence. On the other hand, its power was considered so great that it could give asylumXX. The imperial cult was especially connected with the army as it was on that body the imperial power was ultimately based. Each military camp had a shrine with effigies of gods and genii, where standards and emblems with images of the emperor were placed when the troops were not in combat.

When the Roman world adopted the tondo portrait, it was primarily connected with triumphs and funerals. As is apparent from the passage by Pliny quoted above, the upper class used the motif in particular to accentuate its own glory. We have already noted that Roman society contained, at one and the same time, both considerable social mobility and a marked class consciousness, expressed by, among other things, a well-defined iconography. Throughout the entire period and strikingly so under the Empire private art was dependent on the idioms of state artXXI. Around the beginning of the imperial period the tondo motif became popular, especially in the sepulchral art of the middle class, and in many parts of the Roman world sepulchral reliefs were dominated by this portrait for several hundred years. When, under Hadrian, sarcophagi began to be fashionable in Rome, the motif was transferred to them (fig. 9). This continued throughout the remainder of the Empire and on into the Byzantine period and enjoyed, at times, great popularity. On a sarcophagus the tondo can be placed statically on the front of the coffin itself or on its lid, or it can be borne forth by victories, putti or, as on the sarcophagusXXII represented in the Terme Museum in Rome, by sea centaursXXIII.

The miniature form, as in the Boscoreale phiale or Thorvaldsen’s silver dish-head, was probably intended for the room devoted to family tradition, and in all probability our silver head had its place in the lararium. The latter, which can best be compared with a domestic chapel, was originally located in the atrium, but during the Imperial period it could be found in almost any of the rooms in the house. Statuettes of domestic gods, lares and genii were placed in the lararium, and if the house owned a statuette or miniature bust of the Emperor, it was usually to be found here as an expression of the family’s solidarity with society and its ruler. We know of a number of cases in which portraits of relatives or persons close to the houseowner — living or deceased — were also housed in the larariumXXIV.

The lararium could exhibit great variety of size and form. A considerable number are found in PompeiiXXV, most of which are no larger than a Catholic reliquary. Often they are formed like the fronts of small temples, aediculae, built into the wall so that they form a niche. Not a few are of wood; among these are cupboards with doors like those used for ancestral masks, which we happen to know from representations in painting or reliefsXXVI. Larger lararia were often provided with a series of steps, on which statuetts, miniature busts, phiales with effigies or for sacrificial purposes, etc., could be placed.

In practice it was, of course, possible to lean a phiale against the next step, but it could also be placed on a stand. Moulded – that is, turned — wooden pedestals must have been used. No actual examples have been preserved, but there are representations of them in other materials. From a burial site near Salzburg in Austria comes a portrait phialeXXVII (fig. 10)XXVIII of approximately the same size as the Boscoreale phiale and of about the same age as Thorvaldsen’s silver head. The material is terracotta, and the form of the clay reproduces the metal prototype down to the very last detail. A stand with no organic function is attached to the disc; it must reflect the wooden stand of the metal original. Similar wooden stands are to be found in sepulchral painting. A mural in a columbarium from the Via Portuense outside the walls of RomeXXIX depicts two aedicula niches with portrait tondi of a young married couple. Beneath both circular pictures the top part of the moulded pedestals that bore these clipeatae imagines is suggested by the use of a dark brown, wood-coloured paint.

Pompeian murals exhibit numerous examples of still-life arrangements, in which silver objects of different kinds — both sacred and secular — and, in some cases, statuettes are represented among various victualsXXX. The articles are often placed on a series of steps similar to those to be found in the larger lararia. The restaurants of the towns near Vesuvius and of Ostia were equipped with a corresponding device above their counters, on which cutlery, crockery and food could be placedXXXI. The Romans were, then, familiar with such decorative arrangements.

Roman class consciousness was accompanied by a pleasure in status symbols. As we can learn from, among others, the poet Martial (ca. 40-102 A.D.), even the modestly wealthy often visited each others’ homes, and if one had acquired something of value, it had, of course, to be seen. Although the Romans also used tables for their domestic exhibitions, these steps seem to have been quite popular. In their function and in the meaning they held for their owners, they might well be compared with the impressive bookcases which are the pride of many modern homes, and which are by no means always filled with books.

The placing of the little tondo portrait between statuettes of gods and miniature busts would also give associations with the shrines in military camps where the standards were kept, and this would have been very apposite if its subject was a military personage as the wrinkled brow suggests. Such a placing in the lararium, and thus in a cultic context, in which the tondo bust corresponds to the imperial emblems of the standards, should only be seen as one among many examples in Roman art of iconographic borrowing. The religious aura that surrounded the imperial portrait was not transferred to private portraits although they were placed side by side. It is not so many years since family portraits in oval and circular frames side by side with crucifix were a common sight in Danish homes. The Romans had never actually practised ancestor worshipXXXII, and, as with us, the portrait of a deceased family member was connected rather with common veneration or pride.

Although the various types of monuments had very different chances of survival, there is strong evidence that “memorial portraits” enjoyed considerable popularity during the Imperial period. Very few portraits in precious metal have been preserved, and these have as a rule been found by chance as buried treasure, but that the tradition flourished is shown by the golden glass portrait medallions, of which several are known from the middle and later part of the EmpireXXXIII.

During the Republic and during the major part of the Imperial period the portrait tondo was employed to represent, to an equal degree, gods, emperors and ordinary mortals. In late Antiquity at the transition to the Byzantine period, however, a change took place that was probably connected with the change already undergone by the Roman portrait as the representation of an individual physiognomy. The tondo portrait was now reserved for the emperor, his family, a few highly placed administrators and — first and foremost — the church. The haloed portrait became dominant.

Not until the Renaissance did the upper class and the wealthy middle class return to the tondo portrait, which then continued, via classicism, right through the 19th century, not least in sepulchral art (figs. 11 and 12). And these two periods — 19th century Europe and Imperial Rome in the 2nd century — exhibit not a few similaritiesXXXIV.

As a sculptor Thorvaldsen made a considerable contribution to the continuance of the motif. It was, however, not only in choice of motifs that Thorvaldsen kept close to Antiquity. The techniques he used were largely the same, and his great atelier in Rome was organized along the same lines as the great ateliers in Imperial RomeXXXV. Moreover, few sculptors have created such excellent “Roman” copies of Greek originals as ThorvaldsenXXXVI.

Fig. 11. Bertel Thorvaldsen: Monument to the painter Andrea Appiani (1754-1817). Marble. Height: 485 cm. Erected in 1826. Cf. A601. Brera, Milan.

Even though Thorvaldsen chiefly sought his models in Roman AntiquityXXXVII, he preferred the profile form for his tondo portraits (fig. 11) to the en face form, which had been most commonly used in Ancient Rome. In this he followed his slightly older Roman colleague Canova, and hence the tondo portraits of both artists are reminiscent of enlarged coin portraits, though, of course, the latter are in fact tondo portraits too. Thorvaldsen’s contemporary, the Englishman Sir Richard Westmacott, who in 1793 arrived in Rome to work in Canova’s atelier, preferred the frontal bust as in the sepulchral monumentXXXVIII for Francis Basset, Lord de Dunstanville (fig. 12). Here we meet a real Roman, clad in a Greek himation.

Above the epitaph for Johann Philipp Bethmann-HollwegXXXIX a bust emerges from a background of acanthus leaves bounded by a half tondo, a lunette-shaped niche, and returning to fig. 11, the sepulchral monument for the painter Andrea AppianiXL, we cannot fail to note its antique inspiration. Although, unlike, for example, the sepulchral monument for Vacca BerlinghieriXLI, which bears a corresponding portrait tondo, this monument is not actually formed as a sarcophagus, the cornice is clearly derived from a sarcophagus lid with masks at the corners as in fig. 9. Furthermore, the three Graces with the little cupid on the monument are closely related to the naiads and putti on the Roman sarcophagus. The portrait of the deceased, in tondo form, is centrally located on both monuments.

Thorvaldsen cannot have known that, besides being a portrait “of excellent art”, the little silver head that he bought for his collection represented one of the antique motifs to which he devoted so much of his art. Had he known, it would no doubt have been a source of pleasure to him.

Anvendte forkortelser: AbhGött. Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen; ArchAnz. Archäologischer Anzeiger; Jdl. Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts; Mem AmAcadRome Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome; MonPiot Fondation Eugène Piot. Monuments et Memoires; ProcAmPhilSoc. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Societv; RömMitt. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Römische Abteilung.

Last updated 11.05.2017

[The author’s note in the text] Inv. No. H1951. L. Müller, Thorvaldsens Museum III, Copenhagen 1847, IV n. 1 (p. 148; A. Radnoti in Folia Archaeologica 6 (1954) pp. 49-67; G. Boesen, Danske Museumsskatte, Copenhagen 1967, pl. 162.

[The author’s note in the text] On Thorvaldsen’s purchases of works of art, see D. Helsted, ‘Thorvaldsen as a Collector Apollo (Sept. 1972) p. 206-227.

[The author’s note in the text] The piazza disappeared during Mussolini’s destruction of the city centre, see A. Cederna, Mussolini Urbanista, Rome 1979, p. 144ff.

[The author’s note in the text] H. de Villefosse in MonPiot 5 (1897) Cat. No. 2; Pompeji. 19. April bis 15.Juli 1973, Villa Hügel, Essen, No. 137. On the type, see D.E. Strong, Greek and Roman Gold and Silverplate, London 1966, p. 151f. The Boscoreale phiale, which is probably of the late Augustan or Julian-Claudian period, is more carefully worked at the back of the head than Thorvaldsen’s silver head, which corresponds to conditions found in larger sculpture. In the early Imperial period round sculptural portraits are nearly always finished at the back; later this is omitted, if the portraits are designed for a niche.

[The author’s note in the text] H.B. Walters, Catalogue of the Silver Plate in the British Museum, London, 1921, No. 26; Pompeji (op.cit., note 4) No. 143.

[The author’s note in the text] Fig. 7. Silver phiale with tondo portrait. From Boscoreale near Pompeii. Diameter 24 cm. 1st century A.D. Louvre, Paris.

[The author’s note in the text] For the portraits of Antoninus Pius, see M. Wegner, Die Herrscherbildnisse in antoninischer Zeit, Berlin 1939, Chap. II and K. Fittschen, Katalog der antiken Skulpturen in Schloss Erbach, Berlin 1977, Nos. 26 and 27.

[The author’s note in the text] The best treatment of Antoninus Pius’ coinage is in P.L. Strack, Untersuchung zur römischen Reichsprägung des zweiten Jahrhunderts III, ‘Die Reichprägung zur Zeit des Antoninus Pius’, Stuttgart 1937; see also H. Mattingly, Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum IV, ‘Antoninus Pius to Commodus’ (= BMC, Antoninus Pius — Commodus), London 1940 (rev. reprint 1968). There are excellent pictures in J.P.C. Kent – M. and A. Hirmer, Roman Coins, London 1978, figs. 302ff.

[The author’s note in the text] Müller (op.cit., note 1) Anhang No. 358; BMC Antoninus Pius. The minting of these coins in celebration of the 900th anniversary lasted several years, see Ph.V. Hill, The Undated Coins of Rome, London 1970, particularly p. 101. The celebrations probably took place in 148 A.D., see A. Garzetti, From Tiberius to the Antonines, London 1974, p. 701.

[The author’s note in the text] This is shown by, among other things, the discussion of the golden bust of “Marcus Aurelius” found in Avenches (Aventicum) in Switzerland, which has recently been identified as a portrait of Julianus Apostata, see J.Ch. Balty, ‘Le prétendu Marc-Aurele d’Avenches’ Eikones. Festschrift H. Jucker, Bern 1980, p. 57-63. On miniature imperial portraits, see B. Schneider, Studien zu den kleinformatigen Kaiserportraits (Diss.), Munich 1976. Director Dr. E. Künzl, Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum in Mainz, is preparing a study of imperial portraits in precious metals based on two miniature portraits in silver of emperors from about 300 A.D., which are located in the museum in Mainz.

[The author’s note in the text] K. Fittschen, ‘Ein Bildnis in Privatbesitz — Zum Realismus römischer Porträts der mittleren und späteren Prinzipatzeit‘ Eikones p. 108-114. For the private portrait in this period in general, see G. Daltrop, Die Stadtrömischen männchlichen Privatbildnisse trajanischer und hadrianischer Zeit, Münster 1958.

[The author’s note in the text] See P. Zanker, ‚Prinzipat und Herrscherbild‘ Gymnasium 86 (1979) p. 52-68.

[The author’s note in the text] One of the most pronounced examples is Domitian, who underwent a virtual metamorphosis on coming to power, see G. Daltrop — U. Hausmann – M. Wegner, Die Flavier, Berlin 1966, p. 30ff. His father, Vespasian, had himself represented with veristic hideousness, bald and toothless, as we see him in the portrait in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, V. Poulsen, Les portraits romains II, Copenhagen 1974, N. 3. Vespasian’s portrait proclaims him to be a bulwark for the ancient Roman virtues in contrast to the oriental despotism of his predecessor Nero.

[The author’s note in the text] See O. Brendel, Prolegomena to the Study of Roman Art, New Haven and London 1979, passim. These questions are further discussed in my book, Romersk kunst som propaganda – Aspekter af kunstens brug (Roman art as propaganda – aspects of the use and function of art in Roman society), Copenhagen 1976, which is to be published in English in a revised edition.

[The author’s note in the text] For portraits of Trajan and his staff, see W. Gauer, Untersuchung zur Trajanssäule I, Berlin 1977, p. 60ff. Corresponding differences between individual portraits are to be found on other state reliefs. A striking example, which also demonstrates the restriction to which the imperial portrait was subject, is to be found in the placing of Marcus Aurelius together with his son-in-law and the General Pompeianus on 9 out of 11 reliefs from an otherwise no longer extant triumphal arch from 176 A.D. Pompeianus has a tonsorial style whose representation of individual strands corresponds to what we meet in the imperial portrait after Caracalla, that is, almost two generations later; for the Pompeianus portrait, see I. Scott Ryberg, Panel Reliefs of Marcus Aurelius, New York 1967, p. 77ff., cf. also A. Bonanno, Portraits and other Heads on Roman Historical Reliefs up to the Age of Septimius Severus ( = B.A.R. — S6), Oxford 1976 p. 117ff. and N. Hannestad, ‘The Liberalitas Panel of Marcus Aurelius’ Analecta Romana VIII (1977) p.79ff. with references. In isolation a portrait can be completely misdated, if it is judged on hairstyle alone. This applies to the portraits of Aelius Caesar, which have generally been placed in the High Antonine period, although almost all preserved portraits can with a fair degree of certainty be dated to 137-8 A.D., see N. Hannestad, ‘The Portraits of Aelius Caesar’ Analecta Romana VII (1974) p. 67-100.

[The author’s note in the text] Regarding its origin — as with the origin of the Roman portrait — there are, however, conflicting views, cf. R. Winkes, Clipeata Imago (Diss.), Bonn 1969, p.8f. Winkes’ own definition (cf. p. 61) is more concerned with function than form. For this reason he does not include miniature tondi, unless they are set on a standard. In reality Winkes is arguing in a circle.

[The author’s note in the text] Actually the Roman year 259 = 459 B.C. This must, however, be an error since these two men were Consuls in 79 B.C. (= year 675 after the foundation of the city). The Temple of Bellona was not inaugurated until 296 B.C. The date 79 B.C. is in better correspondence with the other literary sources that we have, cf. Winkes p.35ff. In the year 78 B.C. M. Aemilius hung portrait shields on the facade of Basilica Aemilia facing Forum Romanum. These are represented on coins issued in 61 B.C. by another M. Aemilius, see M.H. Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage I-II, Cambridge 1974, No. 419, 3a-b with references.

[The author’s note in the text] A good overview of the tondo motif is to be found in C.C. Vermeule, ‘A Greek Theme and its Survivals’ ProcAmerPhilSoc 109 (1965) p. 361-397. Winkes includes some represented in murals, see catalogue under Pompeii, cf. also Rom No. 24. For the motif in painting, see also H. Blanck,‘Porträt-Gemälde als Ehrendenkmäler’ Bonner Jahrbücher 168 (1968) p. 1-12.

[The author’s note in the text] A clear example of a portrait medallion is the gold tondo bust, only 6.7 cm. in diameter, of a general from the middle of the 3rd century, which derives from Egypt, Handbook, Nelson Gallery of Art, Atkins Museum, Kansas City 1959, p. 40. On phalerae, see P. la Baume, Römische Kunstgewerbe, Braunschweig 1964, p.299ff. A group of imperial portraits from harness is discussed by W.-D. Heilmeyer, ‘Titus vor Jerusalem’ RömMitt 82 (1975) p. 299-314. For imperial portraits on standards, see Winkes p. 39f. and Schneider (op.cit., note 10) p. 109ff. and in a military context in general, Schneider chap. III.

[The author’s note in the text] Criminals could obtain protection by owning a statuette of the emperor, and if an officer could reach the shrine where the standards ornamented with the imperial portrait were kept, he was protected against mutinous soldiers just as the church altar afforded sanctuary during the Middle Ages, se J.P. Rollin, Untersuchungen zu Rechtsfragen römischer Bildnisse (Diss.), Bonn 1979, p. 143ff.

[The author’s note in the text] Taking his point of departure in sepulchral symbolism H. Wrede, ‘Das Mausoleum der Claudia Semne und die bürgerliche Plastik der Kaiserzeit’ RömMitt 78 (1971) p. 125-166, discusses some central aspects of middle class iconography in this period. Wrede goes thoroughly into the theme in his new book, Consecratio in formam deorum, Mainz 1981.

Please see p. 43 in the original facsimile scan.

[The author’s note in the text] W. Helbig, Führer durch die öffentlichen Sammlungen klassischer Altertümer in Rom, Tübingen 1969, No. 2146. I am indebted to Prof. Dr. K. Fittschen for sending me photographs taken by his wife, Gisela Fittschen-Badura, and for permission to publish them. For the clipeus motif, see K. Schauenburg, ‘Die Sphinx unter dem Clipeus’ ArchAnz 1975, p. 280-295, cf. also H. Brandenburg, ‘Meerwesensarkophage und Clipeusmotiv’ Jdl 82 (1967) p. 195-245.

[The author’s note in the text] See Schneider (op.cit., note 10) p. 156ff. See also Scriptores Historia Augusta, which notes that even in late Antiquity many homes still had portraits of Marcus Aurelius in their shrines. Among the recent finds from Ephesos a group of miniature portraits executed in ivory from about 220 A.D. (J. Inan – E. Alföldi-Rosenbaum, Römische und fruhbyzantinische Porträtplastik aus der Türkei, Mainz 1979, No. 157-160) has been interpreted as effigies of the Imperial family set up in a private house, see Jane Fejfer, Ikonografisk-historisk undersøgelse over portrætopstillinger af det severiske dynastis kvinder (unpublished prize paper) Århus Chap. III note 90. On household gods and their cult, see K. Latte, Römische Religionsgeschichte, Munich 1960, p.89ff.

[The author’s note in the text] See G.K. Boyce, Corpus of the Larario of Pompeii (= MemAmerAcadRome 14), Rome 1937.

[The author’s note in the text] There are several examples of such ancestral masks represented on sepulchral monuments, see A.N. Zadoks-Josephus Jitta, Ancestral Portraiture in Rome, Amsterdam 1932, Pl. IV-V. The form can also be transferred entirely to stone, see W. Trillmich, Das Torlonia-Mädchen [= Abh Göttingen Fig. 3 No. 99), Göttingen 1976.

Please see p. 44 in the original facsimile scan.

[The author’s note in the text] N. Heger, Salzburg in römischer Zeit [= JMS 19, 1973), Salzburg 1974, No. 66. I thank Director, Senatsrat Dr. A. Rohrmoser for sending the photograph.

[The author’s note in the text] Winkes (op.cit., note 16) Rom 24. A good colour reproduction of the woman’s portrait is to be found in R. Bianchi Bandinelli, Rome: The Centre of Power. Roman Art to A.D. 200, London 1970, fig. 99.

[The author’s note in the text] Arrangements of silver on tables were also common. For these arrangements, see J.-M. Croisille, Les natures mortes campaniennes (= Coll. Latomus LXXVI), Brussels 1965.

[The author’s note in the text] See T. Kleberg, Hôtels, Restaurants et cabarets dans l’antiquité romaine, Uppsala 1957, cf. also L. Hannestad, Mad og drikke i det antikke Rom, Copenhagen 1979, p. 105ff.

[The author’s note in the text] Cf. Rollin (op.cit., note 20) p. 21ff.

[The author’s note in the text] A. Alföldi, ‘Römische Portraitmedaillons aus Glas‘ Ur-Schweiz 16 (1951) p. 66-80.

[The author’s note in the text] Culturally this Roman period had many “bourgeois” characteristics, expressed not least in an interest in the decorative. The wealthy Roman collected antiquities, as Thorvaldsen did, and often had a weakness for curiosities from Egypt. If he could not acquire an original object, he bought an imitation, often in miniature. Few periods have left so much bric-à-brac behind them.

[The author’s note in the text] In the great copyist ateliers of Imperial Rome it was the practice to work with full-scale plaster casts, which could, if desired, be sawn up and resurrected in new forms. As opposed to what had been the norm among earlier generations of sculptors, Thorvaldsen also worked with full-scale plaster casts, see D. Helsted ‘Thorvaldsens Arbeitsmethode’, Bertel Thorvaldsen, Untersuchungen zu seinem Werk und zur Kunst seiner Zeit. (Hrsg. G.Bott), Cologne 1977, p. 7-38. On eclectic Roman statues, see in particular P. Zanker, Klassizistische Statuen, Mainz 1974, p. 76ff.

[The author’s note in the text] Particular attention should be directed to the bust of Homer (Else Kai Sass, Thorvaldsens Portrætbuster I, Copenhagen 1963 p. 42ff.). It was copied from the Farnese Homer, which is now in the museum in Naples (G.M.A. Richter, Portraits of the Greeks I, London 1965, p. 50 No. 7). Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, who was strongly inspired by Winckelmann and in 1768-72 published a considerable work on antique sculpture, also copied the Farnese Homer (Die Skulpturen der Sammlung Wallmoden, Archäologisches Institut der Universität Göttingen 1979, No. 52 — K. Fittschen). Both artists restored antiques, an art that Cavaceppi both practised and theorized about on a wide scale. A comparison of the two copies of a copy clearly shows that in contrast to Thorvaldsen Cavaceppi was unable to liberate himself from the style of his time. On the restoration of antiques in this period, see M. Moltesen, Restaurering — før og nu, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek 6. Dec. 1980 – 31. Jan. 1981.

[The author’s note in the text] On ancient motifs used by Thorvaldsen, see J. Birkedal Hartmann, Antike Motive bei Thorvaldsen (ed. K. Parlasca), Tübingen 1979.

Please see p. 48 in the original facsimile scan.

[The author’s note in the text] Bertel Thorvaldsen. Ausstellung Kunsthalle Köln 5.Febr. — 3. April 1977, No. 60. A corresponding setting was intended for the bust in the uncompleted sepulchral monument for Auguste Böhmer, which was designed in the form of a Roman sepulchral altar, see Sass (op.cit., note 34) p. 205ff. with architectural draft p. 209 and Bertel Thorvaldsen (op.cit., note 33) p. 449-459 (B. Bott).

[The author’s note in the text] Sass (op.cit., note 34) II, p. 79ff.

[The author’s note in the text]

Sass (op.cit., note 34) II, p. 189ff.