Friedrich Nerly: Buffaloes Dragging a Block of Marble, B133

This paper interprets Friedrich Nerly’s Buffaloes Dragging a Block of Marble as a meta-painting satirizing classicist tradition by means of a profane, humorous and physical realism.

A talk held at the Istituto Svedese di Studi Classici a Roma for the conference Another Horizon. Northern Painters in Rome and Naples 1814–1870, October 20th, 2015.

Friedrich Nerly: Buffaloes Dragging a Block of Marble, B133

The art work I will address today is this painting by the German painter Friedrich NerlyI depicting a herd of buffaloes struggling hard to drag a huge block of marble marked with Thorvaldsen’s name – see belowII – through the Campagna. The painting is in the collection of Bertel Thorvaldsen, and it was commissioned by the sculptor as a replica of Nerly’s first painted version of 1831 which became instantly popularIII.

Nerly’s image has been read as a praise to Thorvaldsen’s fame. Here, however, I will read this genre painting as a meta-work, or a critical satire of Thorvaldsen’s works, and of Neoclassical sculpture in generalIV. I should perhaps start by saying that my interpretation of the painting is not founded on anything that Nerly or Thorvaldsen said about it, as there are no (known) sources preserved on this. However, in order to make it plausible that Nerly may have had a satirical, or critical purpose in mind, I would like to briefly draw your attention to the so-called Ponte Molle societyV. This was a party club – so to speak – for German and Scandinavian artists residing in Rome during the 1820s and 30s. Nerly was appointed “Generalissimus” or president of this society in 1829, and his title was abbreviated to P.P.Q.P, that is Presidente Populusque PontemollicusVI. The abbreviation – P.P.Q.P – was of course an ironical reference to the S.P.Q.R.VII of Roman antiquity. Nerly organised the festivities of the society in this humorous and satirical spirit, as an almost Dadaistic mockery of historical and social conventions. The Ponte Molle Society is a rather interesting subject, but time does not allow me to go into it in depth. Suffice it to say that this was an artistic milieu in which free irony, satire and platitudes flourished, and it is in this context that the critical perspective of Nerly’s painting seems to fit in very well.

I think you will agree with me that the painting oozes of humour. But what exactly is it that makes it funny? I will try – perhaps somewhat recklessly – to explain that: For me, there are three main qualities in Nerly’s work that can be read in a satirical-humorous perspective:

1. Something heavy |

2. Something moving |

3. Something physical |

Firstly, there is a burden in the shape of this very heavy block of marble. Secondly, it is being moved. And thirdly, the transportation takes place with great difficulty, there is a lot of hard labour and physicality involved.

1. The heavy lump of marble seems to be a simple but effective way of claiming that the tradition of ancient marble sculpture, as revived by Thorvaldsen and Neoclassicism, has become a burden – literally, ideologically, and in any other way. When you look at the buffaloes, they stagger under the weight, drool drips from the mouth of one, and you can glimpse the bloodshot eyes of another.

Faltering buffaloes, drool dripping from mouth, bloodshot eyes

It is as if the animals are appealing to us with an agonising Why? Nerly has tried to establish an identification between the viewer and the buffaloes by means of empathy and by making eye contact with five of the six animals, while none of the humans are looking at us. It is as if the buffaloes are pleading with us: “Why is this torture necessary? Why must this absurd scene go on? Why can’t we be set free like the buffaloes in the background?”

And of course this appeal from the buffaloes is to be understood metaphorically as a plea for a new contemporary and modern art, that should be set free instead of being forced to haul antiquity around like a much too heavy baggage. Tradition is just a drag! It has become a dead weight for a contemporary art – Nerly’s painting seems to claim.

And then take a look at the man sitting on top of the marble block. Unlike the other workmen, he does not seem to be contributing anything of substance to the ordeal. He strikes an elaborate pose similar to those taught in drawing classes at the academies as part of the classical curriculum of the time. Indeed, he is so artful that he seems to represent a statue on its plinth, embodying – and umasking – the ideology and practice of classicism as an empty, obsolete poseVIII.

2. If we then look at the second point – the motif of transportation and its satirical potential – we can turn, for example, to the Swedish painter Egron LundgrenIX who visited Thorvaldsen’s studios in 1841X. He wrote critically about the factory-like production of the sculptor’s works, and their huge dissemination all over Europe: “Generally speaking one would be inclined to find something repulsive in the mobility of art works. Our time does injustice to art by turning it into a commodity…” Lundgren seems to imply that the artistic and metaphysical quality of a statue is closely linked to the basic fact that it stands still on its pedestal. The word statue, as you all know, is derived from the Latin verb stare, to stand. When a sculptor produces too many works for an art market sculpture is literally being debased – that is, taken down from its base, unhinging the very nature of sculpture. Modern times turn sculpture into commercial moveable objects, thus profaning it, and robbing it of its status as art – Lundgren seems to claim.

And if we turn very briefly to WinckelmannXI, we would never hear him substitute his “stille Grösse” with “beweglicher Grösse” – movable grandeur. Winckelmann was not into kinetic art – as you all know for sure. This lame joke is just an excuse for pointing to the idea that moving things around – as it is done in this painting – is clearly in many ways at odds with what we normally regard as core values of Neoclassical sculpture.

But Nerly does seem to take pleasure in the destabilising effect of mobility.

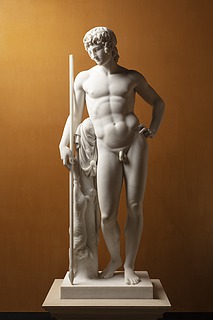

3. The third basic quality of Nerly’s meta-painting is the explicit display of labourXII. This is of course again apparently in open contrast to Thorvaldsen’s Neoclassical sculptures, where any sign of work is completely absent as you can see here for instance:

Unemployed, just hanging around

Adonis, 1808, marble – posthumous version 1887, A790

Thorvaldsen’s figures are famous for their inactivity, some would say laziness, but normally we would characterise this stillness of Thorvaldsen’s statues as a very fine expression of the non-physical, idealistic nature of academic classicism. But when there is labour and workers in an artwork we normally categorize it with the label realism, in contrast to the classicism of Adonis, as in for instance Courbet or Caravaggio. By focusing on the physical effort, Nerly also indirectly criticises the lack of social context in Thorvaldsen’s art – his figures seem to inhabit Arcadia and not the real world. They are lofty abstractions and not physical presences, we would normally say.

To sum up, these three, very briefly sketched main qualities of Nerly’s painting are used as a contrast to the classicism, to which he obviously refers. Nerly uses satire to describe a dogma in academic art that was becoming increasingly outdated in the 1830s. He does not show us Neoclassicism, of course, but hints to it by showing us what it is not, what it lacks.

I have tried to summarise my points in this simple diagram.

| Thorvaldsen Tradition Antiquity Stillness Idleness Arcadia Idealism Classicism Sculpture Etc. |

Nerly Modernity 19th Century Movement Labour Presence Physicality Realism Painting Etc. |

The opposition embedded in Nerly’s meta-painting

Hopefully this diagram is more or less self-explanatory. The terms that I have used in this presentation are arranged in the contrasts that are more or less hidden or built into Nerly’s painting.

And hopefully it is also evident that this opposition is about much more that just Nerly and Thorvaldsen. What we have here is a dogma, or perhaps even a cliché, about the development of art in the 19th Century. If you were an artist around 1800 you would orientate yourself towards the qualities at the left-hand side of the diagram. The hippest thing an ambitious artist would strive for around 1800 would be to produce paraphrases of ancient marble sculpture. But around approximately 1850 a cool artist would lean towards the right hand side of the diagram. So what is shown here in diagrammatic form could also be extended to include a paragone debate in the 19th Century, where sculpture eventually got left behind as dead weight, and painting won the “race”. As you all know, painting was responsible for developing the art forms that we normally associate with modernism – i.e. realism, impressionism, etc. – while sculpture did not seem to become modern for a very long time during the 19th Century. The reason I chose Nerly’s painting for this conference on painters was that it represents this much larger story about this paragone race than what is immediately apparent. Nerly’s satire is a kind of prophecy that painting will become the fittest survivor in the evolution towards modernity by developing itself in opposition to academic classicism as embodied, for example, by Neoclassical sculpture.

One final point, however: Although I have referred to Thorvaldsen’s works, I have by no means intended to characterise them entirely in terms of the features listed on the left-hand side of the diagram. For if we consider that Thorvaldsen himself commissioned Nerly to paint a replica of his satire, should we see the sculptor’s commission as a kind of self-criticism? Or should we perhaps go even further and claim that this cliché or textbook outline of Neoclassicism is not all there is to say about Thorvaldsen’s works? Well, these are rhetorical questions, since my answer is yes – Thorvaldsen’s sculptures can easily be read as much more than the textbook cliché of Neoclassicism on the left hand side of the diagram. His works can without much effort be interpreted in accordance with – and not in contrast to – the three main characteristics of Nerly’s painting listed above.

The research that my colleagues and I are currently undertaking in our archive project corroborates this. First, concerning the weight of tradition: Far from seeing the tradition of classical art as a burden, Thorvaldsen used it in both a light-hearted and serious way, filling his works with many intelligent and subtle references to antiquity. And secondly, regarding mobility: There is a strong dynamic deeply embedded in Thorvaldsen’s works, based on the concept that elements change place and change meaningXIII. And thirdly, regarding physicality, it will suffice to refer to my colleague Nanna Kronberg Frederiksen, also participating in this conference. She has just published an articleXIV on Thorvaldsen’s Venus, that is normally seen as a frigid spinster, but is now interpreted as nothing less than a steaming hot sex goddess.

So my last point today is that, on the face of it, Nerly’s painting is critical towards the textbook reading of Neoclassicism, that I have outlined, and this witty satire would most likely have appealed to Thorvaldsen’s sense of humour. But in acquiring this painting he may have been pointing to an interpretation of Neoclassicism, and his own works, beyond the diagrammatic cliché I have outlined. On another level, then, Nerly’s painting is also critical in the positive sense of the word critique – as an investigative, analytical manoeuvre – because the three main qualities of the painting also characterise another – modern, or perhaps even postmodern – assessment of Thorvaldsen’s so-called Neoclassical works. And that is fun on quite another level.

Thank you for your kind attention.

Last updated 14.02.2024

See the biography of Nerly in this Archive.

Or click on the detail photo here:

Nerly’s first version of the painting from 1831 is at the Staatliches Museum, Schwerin, see Erik Stephan (ed.): Das Unendliche im Endlichen. Romantik und Gegenwart. Malerei, Zeichnungen, Fotografie und Installationen, Jena 2015, p. 62.

There is a sepia drawing of the same motif in the Angermuseum, Erfurt, inv. no. 4173, cf. Thomas Gädeke (ed.): Friedrich Nerly und die Künstler um Carl Friedrich Rumohr, Schleswig 1991, 89, 169.

The version of the painting in the Thorvaldsen collection was probably commissioned a short time after the first from 1831.

At the above-mentioned conference at the Istituto Svedese in Rome in October 2015 I had the pleasant opportunity to meet the German art historian Alexander Kaczmarczyk who referred me to his then unpublished PhD thesis “Die” Antike und ihre Kritiker. Eine ideengeschichtliche und strukturanalytische Studie zur Kunst der Romantik. Here he proposes a reading of works of Friedrich Nerly and his colleague Carl Blechen (1798-1840) as a critique of die Antike by means of a pictorial meta-language.

Although I have not had the opportunity to familiarise myself with Kaczmarczyk’s thesis, it seems that the ideas outlined in the present paper to some extent are overlapping with his understanding of Blechen’s and Nerly’s works as meta-paintings.

See The Ponte Molle Society.

Cf. Lilli Martius: ‘Friedrich Nerly: Ponte-Molle und Cervaro’, in: Nordelbingen. Beiträge zur Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte, Band 41, Heide in Holstein 1972, p. 64.

The famous acronym stands for the Latin Senatus Populusque Romanus – The Senate and the Roman people (or the people of Rome).

The marble block is said to have been used for Thorvaldsen’s statue of Pius 7. in the church of St. Peter, AX392, see a remark in the Kunstblatt 21.3.1839.

If this is the case, the Pope and Catholicism may have been included in Nerly’s satire.

The Swedish painter Egron Lundgren.

See Lundgren’s report dated December 1841.

The German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann.

In the context of Nerly’s motif of labour, it is worth noting that one of the many replicas of the painting is now in the Grohmann Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA - “the world’s most comprehensive art collection dedicated to the evolution of human work”, as the home page proudly states.

The Grohmann replica is made by Nerly’s son: Friedrich Paul Nerly (1842-1919)

Transporting Marble to Thorvaldsen in Rome

Oil on canvas, The Grohmann Museum

See for instance Shifting of Attributes – a Fundamental Feature in Thorvaldsen.

See Nanna Kronberg Frederiksen: Venus Priapus.