This article documents a set of interior sculptural decorations at the former Hams Hall manor house, now demolished, in Warwickshire, England, consisting of Thorvaldsen’s frieze Alexander the Great’s Entry into Babylon, in terracotta, cf. A508, and five marble reliefs. Hams Hall burned down in 1890, and was rebuilt one year later; it was finally razed in 1920. While the marble reliefs were sold at auction in 1926, including one to Thorvaldsens Museum, the fate of the frieze has not yet been determined.

Even when printed in black and white, information sometimes goes overlooked—even in its most relevant context. This was the case with Thorvaldsen’s interior sculptural decorations in Hams Hall, which were long lost to history despite having been thoroughly accounted for in a 1909 biography. The biography at issue, entitled Life of Lord Norton, traces the career of the British politician, philanthropist, and man of means Charles Bowyer Adderley, also known as the 1st Baron Norton; and it explicitly lists the artworks by Thorvaldsen then installed in Adderley’s manor, Hams Hall, in Warwickshire east of Birmingham. Life of Lord Norton goes into considerable detail about the works, motifs, and materials that made up these interior sculptural decorations; it indicates which works were gifts by Thorvaldsen, which works were commissioned from him, and approximately when each work was produced and acquired. Nevertheless, the Hams Hall commission has gone almost entirely unnoticed in Thorvaldsen research—this despite the fact that Life of Lord Norton makes mention of a commissioned terracotta version of the Alexander Frieze, cf. A508; and that is uniqueI, as other contemporary accounts exclusively refer to commissions of the frieze in plaster and marble.

The manor house Hams Hall, Warwickshire, England, where Charles Bowyer Adderley had Thorvaldsen’s frieze Alexander the Great’s Entry into Babylon, in terracotta, cf. A508, installed in the entrance hall. Photograph from Lost Heritage / England’s lost country houses.

In North Warwickshire, England, a bucolic manor estate, Hams Hall, was once found near the village of Lea Marston. From 1637 until its sale in 1920, Hams Hall was in the possession of the Adderley family. In Charles Bowyer Adderley’s day, the appearance of the main building was marked by its restoration and expansion in 1764, a project that presumably was executedII by the English architect Joseph Pickford (1734-1782). Adderley inherited the manor from his extremely wealthy great-uncle, who bore the same name: Charles Bowyer Adderley (1743-1826).

When the younger Adderley purchased works by Thorvaldsen for Hams Hall in 1836, he did not yet reside at the estate, which was at that point rented outIII to Lady Jane Rosse (17??-1838, widow of Lawrence Harman Parsons, 1st Earl of Rosse (1749-1807). The works were installed during the renovation of Hams Hall in the years 1836-1841IV. In 1890, Hams Hall burned down, leaving only the outer walls standing. The manor house’s paintings, library, and artworks were rescued in time, but the reliefs were covered in sootV. However, there is no indication that the Alexander Frieze was lost at this point; indeed, the contrary seems to be confirmed by a photographVI of the entrance hall in which the frieze is still visible—though the photograph is undated. In any event, the manor house was rebuilt a year after the fire under Adderley’s own direction.

By the time of Adderley’s death in 1905, both the coal mining industry and the Birmingham suburbs had begun to encroach on Hams Hall. In 1911, Adderley’s son Charles Leigh Adderley (1846-1926) sold the manor’s land, followed by the building, to the Birmingham Corporation at public auction. The manor house was demolished in 1920VII, but the building materials were partly reused in the rebuilding of Coates Manor near Cirencester by an American shipping magnate, Oswald Harrison (d. 1925). While the materials from the lower portions of the building were reportedlyVIII resold to Americans, it has not been possible to trace them. In particular, it is at present unknownIX whether the Alexander Frieze from Hams Hall was included in any such sale, or where it is found today.

Hams Hall, no later than 1909. According to William S. Childe-PembertonX, it was at this estate that, in 1851, the constitution of New Zealand was conceived by Adderley and the English politician Gibbon Wakefield (1796–1862). In his capacity as politician and member of the British Parliament, Charles Bowyer Adderley was a major advocate for increasing the British colonies’ autonomy. Photograph from Lost Heritage / England’s lost country houses.

The works by Thorvaldsen at Hams Hall are described as follows in the biography Life of Lord NortonXI, which was published in 1909 (for the numbering of the works, see the chart further below):

The following is a list of Thorwaldsen’s works at Hams—the

two first were gifts from the sculptor, the rest were done to

order:

(1) Singing Genii; (2) Playing Genii; (3) Cupid awaking the

fainted Psyche; (4) Bacchus giving Cupid his first cup; (5)

Cupid’s reception by Anacreon, wounded by dart of poetry in

gratitude. These are all in marble. The terra-cotta frieze (6),

round the cornice of the hall, represents the Triumphal Procession

of Alexander the Great into Babylon—the same as in marble at the

Villa SommarivaXII Como and the QuirinalXIII, Rome. After seeing

the latter, MendelssohnXIV, in his “Letters from Italy and Switzer-

land,” wrote (March 1831): “Never did any piece of sculpture

make such an impression on me. I go there every week and

stand gazing on that alone, and enter Babylon along with the

Conqueror.”

| In marble | Location | |

| 1. The Genii of Music Singing, cf. A586 (gift of Thorvaldsen) |  |

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NMSk 1310 |

| 2. The Genii of Music Playing, cf. A588 (gift of Thorvaldsen) |  |

Location unknown |

| 3. Cupid Revives Psyche, A866 (commissioned work) |  |

Thorvaldsens Museum, A866 |

| 4. Cupid and Bacchus, cf. A408 (commissioned work) |  |

Location unknown |

| 5. Cupid by Anacreon, Winter, cf. A416 (commissioned work) |  |

Location unknown |

| In terracotta | ||

| 6. Alexander the Great’s Entry into Babylon, cf. A508 (commissioned work) |  |

Location unknown |

According to Life of Lord Norton, Adderley acquired the works for Hams Hall during his stay in Rome in 1835-1836. During his first three months in the city, Adderley lived with his sister and brother-in-lawXV on Via Sistina, the same street as Thorvaldsen’s homeXVI. Adderley arrived in December, and continued on in the spring to Sicily, Naples, and Malta; then he returned to Rome for a brief stay in the early summer, before returning to England via France. During this last, brief stay, Adderley apparently lodged as a guest in Thorvaldsen’s home:

“I stayed a little at Rome, en retour, as the guest of Thorwaldsen, whose bas-reliefs now adorn the hall at Hams.”

It is not known with certainty whether Adderley stayed in Thorvaldsen’s own apartment, or in a different room in the Roman boarding house Casa ButiXVII, where Thorvaldsen lived. Still, Adderley’s phrase “as the guest of Thorwaldsen” certainly does suggest the former—as does the fact that he received the two marble reliefs as a gift from Thorvaldsen. These are clear indications of a very friendly relationship between the then middle-aged Thorvaldsen and the young Brit. It is presently unknown whether the works for Hams Hall were commissioned during Adderley’s first stay in Rome or his second.

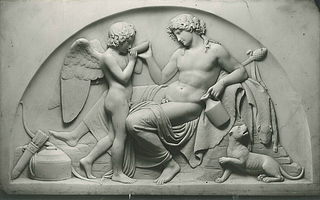

Thorvaldsen’s frieze Alexander the Great’s Entry into Babylon, in a miniaturized and custom-fit terracotta version, cf. A508, in the entrance to Hams Hall. Visible to the right of the door in the middle of the picture is the marble relief Cupid and Bacchus, cf. A407. The placement of the other four marble reliefs is not known with certainty at present, but it is likely that Cupid by Anacreon, cf. A416, was set across from Cupid and Bacchus, i.e., on the other side of the fireplace visible in the picture’s lower right-hand corner. Photograph from Childe-Pemberton, op. cit., p. 22, undated; though according to Kingsley, op. cit., it dates from ca. 1909.

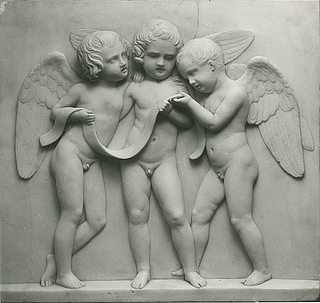

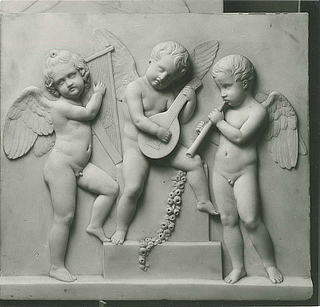

AccordingXVIII to Adderley’s son, Charles Leigh Adderley, the reliefs with small genii singing and playing—cf. A586 and A588 —were presented by Thorvaldsen as allegories to literature and music, respectively. This corresponds only partially to the designations given to one of works in a workshop account dated 21.3.1835 (li tré Geni della Musica [the three genii of music]), and to both works on a list of works transported to Copenhagen in 1835 (in item 12: i due B[assi].i R[iliev].i delli Geni della Musica [the two reliefs of the genii of music]). Here, in other words, we find first the one relief, and then both reliefs, described as depicting the genii of music. The younger Adderley’s notion of an allegory for literature is thus likely a misunderstanding that arose in the family after the fact; or perhaps, though less likely, it was a title invented for the occasion by Thorvaldsen. Given that the biography Life of Lord Norton, op. cit., is based on diaries and letters, however, one may presume that the notion that these reliefs depict singing and playing genii is a credible one, and that the reliefs indeed make up a pair representing the genii of music, namely, song and instrumental music.

It seems certain, in any event, that Just Mathias Thiele’s analysis of the relief’s motifs as singing and playing angels, respectively, in parallel to the interior sculptural decorations in the Novara cathedral, is hardly correctXIX. Despite this, it is as Singing Angels and Playing Angels that the two reliefs have in fact been known throughout the historyXX of Thorvaldsens Museum—until now. The rediscovery of the Hams Hall reliefs and their original designations has now led to a restoration of their original titles: The Genii of Music Singing and The Genii of Music Playing, respectively.

One of the marble reliefs from Hams Hall, The Genii of Music Singing, is found today in Stockholm’s NationalmuseumXXI, where it is still titled Three Singing Angels. The location of its counterpart, the relief The Genii of Music Playing, is currently unknown.

The relief Cupid Revives Psyche, A866, was repurchased for Thorvaldsens Museum at a 1926 auction where five marble reliefs from Hams Hall were put up for sale. The remaining four reliefs, however, were not acquired. The Museum’s director at the time, Theodor Oppermann, declined to purchase them, reasoning that the other marble works were already well-represented in the Museum’s collections; on this see THM j.no. 5a-41/1926 and works A407, A416, A585, and A587. The above photograph is an updated picture of the relief from 2015.

The commission for Hams Hall is not mentioned anywhere among the many thousands of archival materials recovered from Thorvaldsen’s effects, or gathered later from other archives. Nor did Charles Bowyer Adderley leave behind any letters to or from the sculptor—at least as far as is known today. Moreover, the comprehensive encyclopedia of works of sculpture in Britain, A Biographical Dictionary of Sculptors in Britain 1660-1851XXII, makes no mention of a commission for Hams Hall either, even though Thorvaldsen and his other works in British possession are otherwise discussed comprehensively. It has thus been necessary to use indirect means to reconstruct this tale of a demolished manor house with rich interior sculptures.

Among Thorvaldsens Museum’s archival materials, the first clear traces of the Hams Hall commission appear in a Museum journal record from 1926. In April of that year, the Museum had received an inquiry from the London-based auction house Spink & Son, Ltd., which had received five marble reliefs on commission from the then-recently demolished Hams Hall. The heir to Charles Bowyer Adderley’s estate, his son Charles Leigh Adderley, hoped to sell the reliefs as a group, and ideally to Thorvaldsens Museum, which in the view of the family would have provided them with a worthy home. This offer was rejected, however, by the Museum’s director, Theodor Oppermann (1862-1940), who reasoned that the majority of these marble worksXXIII were already well-represented in the Museum’s collections. Accordingly, the Museum purchased only the relief Cupid Revives Psyche, A866, which was missing.

The correspondenceXXIV between Thorvaldsens Museum and the auction house indicates that the reliefs were acquired and commissioned during a stay in Rome between 1820 and 1830. But this conflicts both with what we know of Adderley’s age (he would have then been between 6 and 16 years old) and of his documented stay in Rome during the year 1835-1836. The 1926 correspondence further indicates that two of the reliefs, The Genii of Music Singing, cf. A586, and The Genii of Music Playing, cf. A588, were already completed in marble when Adderley first encountered them, whereas the reliefs Cupid Revives Psyche, A866, Cupid by Anacreon, Winter, cf. A416, and Cupid and Bacchus, cf. A408, were produced in marble only after being first commissioned. The Alexander Frieze, meanwhile, is not mentioned in the correspondence.

Photographs of the proffered works were sentXXV to Thorvaldsens Museum as well, but these were unfortunately not filed in the Museum’s archive of photographs with a clear indication of their provenance. On the contrary, the photographs were mislabeled—at some unknown point—as pictures of the museum’s own marble works with the same motifs, namely, A585, A587, A416, and A407. With this, the Hams Hall reliefs were truly consigned to oblivion. For after the 1926 correspondence was concluded, no one knew what the Hams Hall reliefs looked like; even their precise motifs were partly forgotten. Nor was the matter investigated before now: neither the origins of the reliefs, nor their context, nor the full extent of the interior decorations at Hams Hall.

As for the Alexander Frieze, it appears that it was not included in the 1926 auction in London. Certainly it is not mentioned in the letter from Spink & Son; and the Museum has not received any information since then about any such version of the frieze.

It has been claimed that two of the reliefs from Hams Hall were resold at auctions in 1998XXVI og 2014XXVII, respectively. These are reliefs with the motifs Cupid and Bacchus, cf. A408, and Cupid by Anacreon, Winter, cf. A416. At both auctions, the reliefs were identified as derivingXXVIII from Hams Hall. However, comparison of the auctioned reliefs to the 1926 photographs reveals that these cannot have been the Hams Hall reliefs. The actual provenance of the recently auctioned reliefs is currently unknown.

The rediscovery of Thorvaldsen’s works at Hams Hall was due to commentary work on a letter in Thorvaldsen’s letter archive from a certain F. Alleyne McGeachy to ThorvaldsenXXIX. While the letter is in Italian, it was clearly penned by a foreigner, and indeed one who had gained a hearty familiarity with Thorvaldsen during a previous visit to Rome. In his letter, McGeachy refers to his “brother’s” house in the country, where Thorvaldsen’s works had apparently arrived and been installed, and were eliciting enthusiastic admiration. Because the British politician Forster Alleyne McGeachy had no siblings, he was at first ruled out as a possible authorXXX of the letter. However, in 1834 McGeachy had married Anna Maria Laetitia Adderley (1812-1841), sister to none other than Charles Bowyer Adderley, who was also his best friend and mentor. McGeachy thereby became Adderley’s brother-in-law. And given the many matching circumstantial details—as well as the linguistic quirks and errors in McGeachy’s Italian letter—it is therefore likely that, by the phrase “my brother’s house in the country,” McGeachy was in fact referring to Adderley’s manor house, Hams Hall.

These puzzles in the letter led to a reexamination of the relevant notes in the Museum’s journals, followed by a search for the photographs from the 1926 auction in the Museum’s photographic archive. These turned out to be five photographsXXXI in all, which were filed under different inventory numbers without cross-references or indications of the works’ provenance. As a result, the five photographs—all fine black and white pictures developed on identical photographic paper—were taken to be depictions of the Museum’s own marble reliefs, with their corresponding motifs, and were marked as such by Museum staff in matching inscriptions associating each photograph with the Museum’s own inventory number. The artworks had clearly all been arranged for photographing on the same stand, which can be seen poking out from under the bottom of each relief; all of the photographs have a black background, and in one case, a fragment of another relief is visible in the background. Upon closer inspection, this other relief turns out to be Cupid Revives Psyche, A866 –- the very relief that the Museum purchased from Charles Leigh Adderley, and indeed the only relief for which it has been impossible to locate a photograph that can be traced to the Museum’s correspondence with the auction house. It is conceivable that the Museum returned this photograph in order as an additional precaution, in order to ensure that the correct relief be sent. When all of this evidence is taken together—the correspondence between the matching inscriptions by Museum staff; the identical photographic paper used; the identical stands used for photographing; and the visible fragment depicting the one relief actually purchased by the Museum—it is clear these were indeed the missing photographs of the works from Hams Hall.

An inscription on the back of one of these photographs identifies it as portraying the Museum’s specimen of Cupid and Bacchus, A407. However, a later handwritten note, deriving also from Museum staff, notes that the depicted relief could not have been the museum’s specimen, and that the relief’s actual provenance was unknown. A comparison between the five extant photographs and the museum’s own marble specimens has established that none of the photographs actually depict works in the Museum’s possession. There are differences in the appearance of the marble—e.g., small flaws (such as darker veins) or larger flaws (such as tears or cracks) in the Hams Hall specimens, with no counterparts in the Museum’s reliefs (A416, A407, A585); differences in the treatment of the marble, which in certain cases seem to mark the superiority of the Hams Hall versions (A416, A585); or small differences, as when a wing has a fuller or rounder shape in one version (A587), or when a garland’s tips are somewhat differently shaped (A587), or where there are different cracks in the rear wall (A407). Below the reader will find a work-by-work comparison of each of these marble reliefs from Hams Hall and Thorvaldsens Museum, respectively.

In each of the sets of photographs below, the Hams Hall (HH) artworks appear on the left, while the Thorvaldsen Museum (THM) specimens are on the right.

|

|

The relief The Genii of Music Singing was presented to Adderley as singing geniiXXXII, i.e., as an allegory for song or music (or alternatively—and improbably—literature, as was reported by Adderley’s son; cf. the 1926 correspondenceXXXIII with the auction house). The HH relief is on found today in the Swedish NationalmuseumXXXIV in Stockholm, to which it was donated by Otto Smith, dr. phil.XXXV (1864-1935) in 1928, namely, two years after the London auction of the effects from Hams Hall. It was reportedXXXVI that the work had been purchased one year earlier in London, together with another marble relief, “hos en af de stora konsthandlare der” [from one of the main art dealers there]. Both reliefs must thus have been bought by an art dealer at the auction in 1826, and then resold to Smith in the spring of 1827. Evidence that this relief is indeed the one from Hams Hall includes a crack in the marble over the rightmost genius in the relief, as well as a hole in the marble platform under the right foot of the genius in the middle, both of which are also found in the relief held by the Nationalmuseum, but not in the THM specimen. What is more, the marble carving of the HH specimen appears to be of higher quality than that of the relief owned by Thorvaldsens Museum, namely, A585.

|

|

It is unknown at present where The Genii of Music Playing is found today. But it was likely purchased by Otto SmithXXXVII (1864-1935) in 1927 together with its counterpart relief, The Genii of Music Singing, described above. What is certain is that Smith bought two minor marble reliefs, donated one of them to the Swedish Nationalmuseum (see above), and kept the other for himselfXXXVIII. Thorvaldsens Museum is in possession of the marble specimen A587, which appears—judging by the photograph of the HH specimen—to be a somewhat less well-carved work than Adderley’s relief. In addition, there are a number of minor differences between the HH and THM specimens. For example, the rose garland in the HH relief issues in more roses and fewer leaves than the one in the THM relief; the rearmost wings of the rightmost genius seem longer in the HH relief; and the marble itself seems to be more mottled and veined than in the THM relief.

|

|

As recently as in 2015, the photograph of the Hams Hall relief of Cupid and Bacchus was incorrectly identified as depicting Thorvaldsens Museum’s own marble specimen, A407, despite differences that are evident on closer inspection. These include, first and foremost, the crack or tear at the upper right corner of the HH relief, above Bacchus’s thyrsus staff, which has no counterpart in the THM relief. There are also various cracks in the wall behind the panther on the right; differences in how the grapes in Bacchus’s wreath are carved; as well as a flaw in the marble on Bacchus’s arm in the THM relief, which is absent in the HH specimen.

|

|

The relief Cupid by Anacreon also bears visible differences between its HH and THM versions. For example, the HH relief has darker and more numerous veins than the THM version; there are flaws in the vase pattern at the lower left of the THM relief, compared to the HH specimen; and the bow on Bacchus’s thyrsus staff, on the left side, appears to have been better and more clearly carved on the HH relief, much as the marble treatment generally seems—to judge by the photograph—clearer and more nuanced in the HH version. Most striking is the large crack in the lower lefthand corner of the HH relief, which has no counterpart in the THM version.

Last updated 01.06.2017

A possible complement to this unique case is the terracotta version of the Alexander Frieze that graces the façade of the Casa Bienaimé on Via Guiseppe Verdi in Carrara, the home of Thorvaldsen’s longtime colleague Pietro Antonio Bienaimé. For the exact location, see the map utility Thorvaldsen’s works worldwide. It remains unknown, however, whether this relief was produced on the basis of one of Thorvaldsen’s models by the brothers Pietro Antonio and Luigi Bienaimé, as is indicated in the biographical entry for Luigi Bienaimé in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani [Biographical Dictionary of Italians], vol. 10, 1968 (cf. Treccani), or whether it was cast from the marble version produced for Giovanni Battista Sommariva’s Villa Carlotta, cf. A505, as Sigurd Schultz assumed in his description of the relief (cf. THM j.no. 17I-8/1953 (Schultz’s travel notes), pp. 3-4).

Cf. Nick Kingsley, “Adderley of Hams Hall and Fillongley Hall, Barons Norton,” in Landed families of Britain and Ireland.

Cf. Childe-Pemberton, op. cit., p. 23.

Cf. Childe-Pemberton, op. cit., p. 28.

Cf. Childe-Pemberton, op. cit., pp. 279-280.

As mentioned later in this article, the source for this photograph is Childe-Pemberton, op. cit., p. 22. According to Kingsley, op. cit., the image should be dated to approximately 1909.

Cf. Nick Kingsley, “Adderley of Hams Hall and Fillongley Hall, Barons Norton,” in Landed families of Britain and Ireland.

Cf. Parks & Gardens: UK.

The terracotta frieze that was sold at auction in 1997 by Christie’s in New York was produced in Denmark around 1855, by Rasmus Peter Ipsen. It can therefore be excluded for consideration, assuming that the Hams Hall frieze was installed as claimed during the renovation of the manor house in 1836-1841. Cf. Christie’s, N.Y., East, March 19, 1997, Lot 205 / Sale 7993.

Cf. Childe-Pemberton, op. cit., p. 91. For more on this subject and on Adderley’s involvement in The Canterbury Association, see also Blain, op. cit.

Cf. Childe-Pemberton, op. cit., p. 22.

Namely, the Alexander Frieze in marble, cf. A505, produced for Giovanni Battista Sommariva’s Villa Carlotta by Lake Como in Italy; see the associated entry in the Thorvaldsen chronology. The Hams Hall frieze was a version of this Alexander Frieze, as is clear from the presence of Thorvaldsen’s self-portrait at the far right. That self-portrait is absent from the frieze at the Quirinal Palace, referred to in the next note.

I.e., the first Alexander Frieze, cf. A503, produced between March and June 1812 for the Quirinal Palace in Rome on the occasion of Napoleon 1.’s planned visit to the city.

Namely, the German composer Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. See also the letter dated 1.3.1831, mentioned in Life of Lord Norton, op. cit., p. 22.

Namely, Anna Maria Laetitia Adderley (1812-1841) and Forster Alleyne McGeachy. McGeachy was also Adderley’s friend and mentor; cf. Childe-Pemberton, op. cit., p. 20. While it is at present unknown how long the couple stayed in Rome, they must have arrived before Adderley reached the city in December, and presumably left for home before Adderley returned from his further travels south and east for his second stay in Rome. Had this not been the case, Adderley presumably would have lodged with them once more, rather than (as it turned out) with Thorvaldsen.

For more on Thorvaldsen’s residences, see the Related Article on the subject.

For more on Casa Buti, Thorvaldsen’s home in Rome, see the Related Article on the subject.

Cf. THM j.no. 5a-41/1926.

Cf. Thiele 1848, vol. 1 (text), p. 98-100. For more on the shifting names attached to these reliefs—and specifically, for more on the vacillation between angels and genii—see the Related Article From Genii to Angels and Back.

For more on the subject, see the Related Article From Genii to Angels and Back.

Cf. inv. no. NMSk 1310.

On this see Roscoe, op. cit., pp. 1262-1267, which builds on the work of Rupert Gunni, in Dictionary of British Sculptors, revised ed., London 1968 [1951].

See THM j.no. 5a-41/1926 and works A407, A416, A585, and A587.

Cf. THM j.no. 5a-41/1926.

Cf. THM j.no. 5a-41/1926.

Daniel Katz, Ltd., London 1998; cf. THM j.no. 13-44/1997.

See the auction notice from Sothebys, New York, January 30, 2014, Auction 9107, Lot 139, where the two reliefs were sold together with two others (cf. A353 og A355).

Since 1997, this confusion about the works’ provenance has expanded to include two other reliefs by Thorvaldsen that were put up for sale at the two auctions mentioned here, namely, Pan and a Satyr, cf. A353, and Bacchante and a Satyr, cf. A355. Both of these reliefs are described as likely deriving from Hams Hall in the catalogue by Grandesso and Skjøthaug, op. cit., p. 284 and p. 285, cat. nos. 455.4 and 423.1.

In point of fact, a brief description of the components and provenance of these interior sculptural declarations has been available since 1909 in the biography Life of Lord Norton, cf. Childe-Pemberton, op. cit., p. 22; but this source has nonetheless been lost to history in both the Danish and British contexts.

See also the biography of McGeachy for a more thorough account of this attribution.

The correspondence indicates that four photographs were enclosed. The explanation of the present five photographs must be that one of the original photographs was of The Genii of Music Singing, cf. A586, and The Genii of Music Playing, cf. A588, side by side, as both photographs have clearly been cropped out of a larger picture. This must have been done at the Museum, in order to file each photograph under the appropriate inventory number. No photograph of the work the Museum ended up purchasing, Cupid Revives Psyche, A866, has been located. It is conceivable that the Museum returned this photograph as an additional precaution, in order to ensure that the correct relief be sent.

Cf. Childe-Pemberton, op. cit., p. 22.

Cf. THM j.no. 5a-41/1926. This, however, appears to be an after-the-fact rationalization, or subsequent misunderstanding, on the part of the Adderley family.

Cf. inv. no. NMSk 1310.

See here for more on the art collector and philanthropist Otto Smith, dr. phil., who donated many of the works in his collection to the Egyptian Museum in Stockholm, now part of Medelhavsmuseet [The Mediterranean Museum].

See the letter of donation dated June 2, 1928 from Otto Smith to Axel W.R. Gauffin (1877-1964), director of the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm. I am grateful to curator Linda Hinners for granting access to this material, in correspondence dated November 16, 2015; cf. THM j.no. 2015-0262284.

See here for more on the art collector and philanthropist Otto Smith, dr. phil., who donated many of the works in his collection to the Egyptian Museum in Stockholm, now part of Medelhavsmuseet [The Mediterranean Museum].

See the letter of donation dated June 2, 1928 from Otto Smith to Axel W.R. Gauffin (1877-1964), director of the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm. I am grateful to curator Linda Hinners for granting access to this material, in correspondence dated November 16, 2015; cf. THM j.no. 2015-0262284.