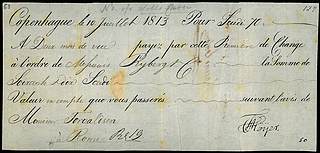

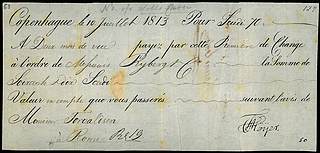

Bill of exchange issued by C. F. Høyer, 10.7.1813

Click on image to magnify

Bill of exchange issued by C. F. Høyer, 10.7.1813

Click on image to magnify

For Thorvaldsen and his contemporaries, bills of exchange played a crucial role in artistic life, forming part of the economic basis for any career in the arts. In the correspondence preserved in the Archives, bills of exchange appear frequently; indeed, many of the events described can only be understood with the aid of insight into their workings. Yet as their use has declined, familiarity with bills of exchange has become exceedingly rare, to the point where it is no longer clear to most readers what a bill of exchange is to begin with. Accordingly, a brief account of this phenomenon is called for and provided here.

Bills of exchange were, roughly speaking, the checks of yesteryear. A bill of exchange is a negotiable document, i.e., one that can be bought or sold. It is issued by a person or institution—the first party—who obligates him-/her-/itself or a second party to disburse funds to a third party. Bills of exchange can be used either as means of payment or as a basis for the granting of credit.

A bill of exchange might be issued, for example, if one wished to borrow money from another, or had money owed to one by another. Under such circumstances, one could issue a bill of exchange to another—or in the parlance of the day, “draw” a bill of exchange upon another (the “drawee”). On could, for example, present a bill of exchange to one’s bank, which could then be accepted—or, perhaps, rejected—by the drawee or the drawee’s bank. Once notice of acceptance (or rejection) of the bill of exchange had been sent on to one’s bank, one could receive one’s money. In practice, this meant that one would sell the bill of exchange to one’s own bank, which could then sell it onward to the drawee or to the drawee’s bank.

Bills of exchange were particularly used in international bank transactions. In order to transfer money to a foreign destination, for example, a person or institution would first establish a line of credit for the recipient at a domestic bank. After receiving notice that this line of credit had been established, the recipient could then issue a bill of exchange for the relevant amount, drawn either on the domestic bank or on behalf of a foreign bank or trading house. The foreign bank would then obtain the domestic bank’s acceptance of (or refusal to accept) the bill of exchange’s validity. At this point, the recipient could sell the bill of exchange to the foreign bank—i.e., withdraw the money from the foreign bank—leaving the foreign bank with the bill of exchange as a receivable for money owed to it by the domestic bank.

Thorvaldsen’s so-called “gratification” from the Foundation for the Support of Cultural and Social Purposes, dated 6.3.1804, was transferred to Italy in just this manner.

The advantage of bills of exchange was that they were negotiable: they could be sold (endorsed) to other parties at many degrees of remove. Whenever a bill of exchange was sold, the new owner assumed all of the obligations associated with it by writing his name on the bill.

When trade between two countries grew sufficiently extensive, it became no longer necessary to transfer actual funds from one country to the other. Instead, the various receivables and payables could be offset by trading of bills of exchange between the countries’ banks. In principle, such offsetting could take place as follows.

Let us assume, for example, that the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen was to transfer 300 rix-dollars to Thorvaldsen in Rome. The Academy could do so via the Danish trading house Ryberg & Co., which would then issue a bill of exchange drawn on the Roman banking family Torlonia on behalf of Thorvaldsen. The bill of exchange would then be sent to Thorvaldsen, who in turn would sell it to Torlonia for the equivalent of 300 rix-dollars in Roman scudi, minus a fee.

To cover its outlay, Torlonia could then draw a second bill of exchange on Ryberg & Co., this one on behalf of an entirely different Dane who was owed a matching sum from an entirely different Italian. The latter Italian would then pay the sum to Torlonia in Rome, while Torlonia would send the second bill of exchange to the Copenhagener in question—who could obtain his money by selling the second bill of exchange to Ryberg & Co.

When redeeming a bill of exchange, it was important to do so at the right place and under the best conditions.

The ever-shifting exchange rates gave bankers or money-changers the chance to earn a pretty penny on trade in bills of exchange.

Sums sent from Denmark to Italy were often denominated in Hamburg mark banco (see the Related Article on Monetary Units), which at the time was the currency least subject to fluctuation in value.

In Thorvaldsen’s day, a number of types of bills of exchange were in circulation.

With an ”avista bill of exchange,” also known as a “sight draft” or “sight bill of exchange,” payment of the relevant amount took place immediately upon presentation of the bill, as the Italian expression a vista [on sight] suggests.

Other types of bills of exchange, by contrast, were to be paid only once a certain period of time had elapsed.

What is more, bills of exchange were often issued in multiple copies (prima, secunda, etc.), where the second or later bills were copies or duplicates of the first.

In today’s Danish, the expression at trække veksler på nogen [to draw bills of exchange on another] is more commonly used figuratively than literally; its figurative meaning is to take advantage of, use, or make taxing demands on another. The same expression is found in the fixed phrase at trække veksler på nogens tålmodighed [to draw bills of exchange on another’s patience], in which one figuratively speaking “borrows” a bit too much of another’s patience.

That the word veksel [bill of exchange] acquired these connotations in the first place reflects the fact that transactions using bills of exchange depended on a mutual trust between the parties, a trust that was occasionally broken. This can be seen, for example, in the Related Article entitled The Only Price I Charge, on the economic relations between Thorvaldsen and his patron Herman Schubart.

In the historic Ordbog over det danske Sprog [Dictionary of the Danish Language], the word veksel [bill of exchange] is defined as follows, cf. Definition 2:

“…a negotiable instrument furnished with special legal powers, by which the issuer commits himself or another party to disburse a sum of money indicated on the document to the holder in due course, either upon presentation of the document or after a set period of time has passed. (Orig. for the exchange of money, particularly in such a fashion that one would pay a sum to a currency trader (moneychanger) in the currency of a certain (one’s own) country, in exchange for the latter’s undertaking of the obligation, via a document (a “letter of exchange”), to pay (or have paid) a corresponding sum in a foreign country in that country’s currency.).”

See also the explanations provided in Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon [Salmonsen’s Conversational Encyclopedia] and Den Store Danske [The Great Danish Encylopedia].

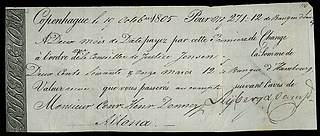

The following bill of exchange, dated 19.10.1805, is found in Thorvaldsen’s archive, despite the fact that the sculptor was not involved directly in the transaction. This bill of exchange is in all likelihood for a transfer of money from the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen to C. F. F. Stanley in Rome. The sum in question was a portion of Stanley’s travel stipend, to which he had applied for an extension in a letter dated 21.9.1805.

Bill of exchange issued by Ryberg & Co., October 19, 1805; click to magnify |

H. Jensen’s declaration on the reverse of the bill of exchange |

This bill of exchange is to be read as follows (click on the photographs to magnify them). It was drawn by the Copenhagen trading house Ryberg & Co. on the Hamburg banker and merchant Conrad Hinrich Donner, on behalf of the presently unidentified Councillor of Justice H. Jensen. According to his own declaration—written on the bill of exchange’s reverse side—Jensen intended to pass the money on to Stanley, who was in Rome during October 1805.

Put more simply, Ryberg & Co. requested that Donner disburse the funds to H. Jensen.

Even though the Academy of Fine Arts is not mentioned on the bill of exchange, the transfer of money must have been initiated by the Academy.

That the document was issued and signed by Ryberg is clear from (among other things) the preprinted signature label along the left edge. H. Jensen must have been a merchant en route from Copenhagen to Rome, whose instructions were first to collect the money from Donner in Hamburg, and then to deliver it to Stanley in Rome. Jensen’s detour to Donner was undoubtedly to ensure that the amount would be converted to Hamburg mark banco, a relatively secure currency (see the Related Article on Monetary Units).

Jensen was presumably furnished with a secondary (secunda) bill of exchange, which he sold to Donner in Hamburg, while the primary (prima) bill is the one depicted here—cf. the designation “Premiere de Change” [First of Exchange]—which was sent by mail to Stanley in Rome.

Stanley died, however, on 18.11.1805, one month after the bill of exchange was issued in Copenhagen, and thus never came to receive the money.

The fact that the original copy of the bill of exchange remains in Thorvaldsen’s archive is a firm indication that the bill was never drawn—that is, sold to Jensen by Stanley—as originally planned. Jensen must therefore have repaid the money to Donner or Ryberg upon his return to Hamburg/Copenhagen.

For another sample bill of exchange, see the one dated 10.7.1813.

Last updated 06.07.2016