Caffè Greco: Art Temple, Post Office and Cosmopolitan Sanctuary

- Karen Benedicte Busk-Jepsen, arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk, 2014

- Translation by David Possen

- 1. A coffeehouse with art on the walls

- 2. A post office and informal information desk

- 3. A cosmopolitan sanctuary and commons

- 4. A new publication space and home for the Artists’ Republic

- 5. The coffeehouses lose ground to the artists’ organizations

- 6. Caffè Greco today: a visit to the past

- 7. References

A coffeehouse with art on the walls

In the late eighteenth century, the coffeehouses of Rome gained increasing significance as gathering-places for the city’s numerous foreign artists and intellectuals, who were then flocking to Rome like pilgrims. Until approximately the middle of the nineteenth century—when artist associations were formed in Rome based on nationality, bringing with them a different, more segregated pattern of social interaction—Rome’s coffeehouses were its most important meeting places and “hangouts.” This was true both for foreigners permanently resident in the city and for those merely passing through, whether these were authors or philosophers, artists or architects, composers or musicians, actors or playwrights. All of these would meet at such places as Caffè delle Nocchie, Lepre, La Chiavica, and Caffè Greco. The last of these came to be almost an institution of its own in Roman artistic and cultural life, specifically attracting a large Northern European clientele.

Antico Caffè Greco, commonly known as Caffè Greco, was one of Rome’s most important artist-cafés from the final decades of the eighteenth century onward. Caffè Greco was (and remains) located on the narrow, busy shopping street Via dei Condotti, which extends a short distance from the Piazza di Spagna, at the base of the Spanish steps, to the main thoroughfare Via del Corso. At Caffè Greco, foreign artists and intellectuals could meet with their countrymen and locals over a cup of the establishment’s authentic coffee, its mezzo caldo (a hot rum toddy), or the newspaper of the day (on this see the news magazine Diario di Roma, which circulated from 1808 to 1836, and has been digitized). It was here that customers would cultivate their contacts, here that they would stay current with news of their acquaintances; it was here that they kept themselves informed about world events; it was here that they held parties, here that they collected their held mail; and it was here that they carried on discussions about art, literature, and politics with like-minded conversation partners—or debated such topics with opponents.

Unknown: Man Reading Diario di Roma in a Café in Rome. Watercolor, 35×28 cm, Thorvaldsens Museum.

Home away from home: A young bohemian in a soft worn coat and hat with the day’s newspapers, from Diario di Roma to Gazette de France and Allgemeine Zeitung. The dog is urinating on Kunstblatt.

The many small connected rooms at Caffè Greco were richly decorated. They remain so today, and now include 150 works by approximately sixty artists: paintings, portrait medallions, busts, and statuettes—including a bronze bust of Thorvaldsen and a portrait medallion of the sculptor in profile. Unusually, the café’s decorations were furnished by artist-customers themselves. The German cultural historian Friedrich Noack (1858-1930) once called Caffè Greco a special kind of temple of art, because artists made a consistent practice of displaying their works there. From a present-day perspective, Caffè Greco can be regarded as a precursor to today’s café galleries. The sale of one artwork would free up space for another, so that the “scene” would periodically change. Caffè Greco’s artist-customers thereby gave the café a unique quality. They must have felt a deep sense of shared ownership of the place, even if it was formally the property of a single man.

A post office and informal information desk

That Caffè Greco emerged as such a magnet for artists and intellectuals can in no small part be attributed to the purely practical circumstance that it also functioned as a mailing address. There were many who stopped by the café each day to ask whether there was poste restante [held mail] for them. The German painter Ludwig Richter (1803-1884) recounts in his memoirs, Lebenserinnerungen eines deutschen Malers [Memoirs of the Life of a German Painter] (1885), that Caffè Greco’s customers felt so comfortable using the coffeehouse as a post office that they frequently had letters containing bills of exchange—i.e., the checks of the day—sent to them there. Letters awaiting pickup were held in a lead letterbox on the café counter, as can be seen in the painting Künstler im Caffè Greco in Rom [Artists at Caffè Greco in Rome] (1856) by the Austrian painter Ludwig Passini (1832-1903). Here we see a painter standing at the counter, leafing through the pile of letters, looking to see if there is anything for him there.

Thorvaldsen too received mail at Caffè Greco, particularly during his early years in Rome. For example, the first letters sent to Thorvaldsen from his father, Gotskalk Thorvaldsen, were addressed to him there; similarly, Thorvaldsen’s lengthy correspondence with the Danish general consul in Rome, J. C. Ulrich, regarding an unsuccessful 1801 attempt to transport works by the sculptor to Danmark, was conducted via the café. Starting in the spring of 1804, however, when Thorvaldsen moved into the boarding house Casa Buti at Via Sistina 46, most of his mail was addressed to him at that private address. Yet toward the end of Thorvaldsen’s life, after having moved to Denmark in 1838, he used Caffè Greco as his mailing address once more during his stay in Rome in 1841-1842. During that period, then, Thorvaldsen must again have stood at the counter, leafing through the contents of the lead letterbox, searching for his name.

Ludwig Passini: Künstler im Caffè Greco in Rom [Artists at Caffè Greco in Rome] (1856).

Aquarelle, 49×62.5 cm, Hamburger Kunsthalle.

In this portrait of the atmosphere at Caffè Greco, Ludwig Passini has included its well-known lead letter box for held mail; the German historical painter Rudolf Lehmann is leafing through the letters.

The coffeehouse served not only as a post office, but also as a kind of informal information desk, where one could gather news about the whereabouts of one’s contacts. An example of Caffè Greco functioning in this manner is found in a letter to Thorvaldsen dated 8.5.1797 from his father, Gotskalk Thorvaldsen, in which the father asks his son to inquire about the Swedish-Italian architect Carlo Bassi at “the Greek coffee house on Strada Condotta.”

The Greek coffeehouse was also the place to go when one was in need of lodging. For example, Hans Christian Andersen wrote in an 1831 diary entry of meeting his fellow author Henrik Hertz at the café and finding him a place to live: “At the café this morning (by which I mean Greco), I was the first Dane Hertz met … I offered him my services in finding him a place to live.” Andersen had himself lived directly above Caffè Greco for a period. Today a framed letter from Andersen to his friend Henriette Collin hangs on the café wall, with a sketch drawing and painterly description of the apartment where he lived together with her husband, the jurist and official Jonas Collin: “We have floor carpeting in every room, views of Rome, and no fewer than four windows. On the balcony roses and wallflowers are in bloom. In the evenings, we light a four-armed Roman lamp, but have a wax candle for each of us as well,” Andersen wrote.

A cosmopolitan sanctuary and commons

For Thorvaldsen, as a longtime resident of Rome, visits to Caffè Greco were part of daily life. From his first year in Rome, 1797, until he left the city in 1838, Thorvaldsen was a near-daily customer at the café; tellingly enough, he often celebrated his Roman brithday there. Many other Danish artists also found their way to the café on Via dei Condotti, including the authors Henrik Hertz and Carsten Hauch, the artists Hermann Ernst Freund, Jørgen V. Sonne, and Albert Küchler, and the actress Johanne Luise Heiberg. Memories of the coffeehouse also remained lively at a nostalgic distance. For a “Roman Banquet” held in 1835 on Thorvaldsen’s Roman birthday at the Society for Civic Virtue, Christianshavn, for which the banquet hall was decorated like “a Roman public house,” H. C. Andersen wrote a song entitled A Little Escape to Rome on March 8, 1835. This song’s fourth verse, written to a German hunting melody, offers an impression of the special Leben that could unfold at Caffè Greco:

Vi ned ad Corso vandre,

Og sikkert vi de Andre

I Caffe greco [sic] see!

Man Velkomst drikke skal jo,

Vi raabe mezzo caldo!

Vi kysses og vi lee!

Hallo, halle, hallo, halle!

Vi er i vor Caffé!

[We wander down the Corso,

We’re sure we’ll see the rest

At Caffè Greco!

A welcome-toast’s a must;

We’ll call out “Mezzo Caldo”!

We’ll kiss and we will laugh:

Hello, hallé! Hello, hallé!

We’re here in our café!]

Despite the sense of Danish ownership articulated here by Andersen, the many guests at Caffè Greco of varied nationalities had little trouble sharing the space with one another. The groups did not segregate themselves by country of origin, but seem to have interacted freely across nationalities and languages. In his 1871 Minder fra min første Udenlandsreise [Memoirs of My First Journey Abroad], Carsten Hauch looked back on this cosmopolitan socializing, describing it as follows: “As long as one shared artistic sympathies with another, one would hardly ask what country the other was born in.” A shared interest in art was what brought people together. It was a power that “tore and carried all along with it like a worldwide storm, so that national feeling—however much one loved one’s fatherland—never led to any sharp divides.”

In point of fact, Germans formed the largest contingent of the café’s clientele. This is why Caffè Greco, which had gotten its name from the coffeehouse’s first Greek owner, Nicola della Maddalena, was also jokingly called Caffè Tedesco, i.e., “the German café.” Among the German regulars, one could meet the painter Joseph Anton Koch, the poet Heinrich Heine (1797-1856), and the composer Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy. British regulars included the trio of Young Romantic poets John Keats (1795-1821), Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), and George Gordon Byron. The Russian author and playwright Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852) and the French author and Winckelmann enthusiast Stendhal were also frequent visitors. This list of famous figures should not, however, disguise the fact that the café’s clientele was broad and inclusive.

A new publication space and home for the Artists’ Republic

Looked at more broadly, Caffè Greco and several other Roman coffeehouses played different and more significant roles than merely as meeting-places of social and practical relevance. They should also be regarded as a completely new type of public space, in which all those who could buy a cup of coffee could enter and find a place: a form of socializing neither defined nor regulated by any social institutions. This type of social space was previously unknown; coffeehouses thus took on great significance for the shifts in the social order toward democratic and republican ideas that took place throughout Europe from the mid-1700s onward. This phenomenon—the significance of coffeehouses for the development of democracy—has been comprehensively described by the philosopher Jürgen Habermas (1929-) in his 1962 book Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit [The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere].

Asmus Jacob Carstens: Self-Portrait (ca. 1785).

The Danish-German artist Asmus Jacob Carstens composed his famous letter declaring his independence from the Academy of Arts of Berlin on February 20, 1796, at Caffè Greco.

In France, cafés had already had marked significance as platforms for a free culture of debate in the decades leading up to the French Revolution in 1789. Cafés arrived only later in Italy, but there too they served as sanctuaries where one could give free expression to opposition to the absolute monarchy or to other hierarchical social institutions, and formulate ideas of a new social order. For the German artists and intellectuals in Rome, Caffè Greco quite clearly served as a sanctuary of this sort. In German literature, the café is mentioned as a home for the Artists’ Republic. It was also at Caffè Greco that the Schleswigian (Danish-German) draftsman and painter Asmus Jacob Carstens wrote his letter of great subsequent fame to the Academy of Arts of Berlin on February 20, 1796, launching a fierce debate about the regulations at the Academy. Carstens refused to travel home to take up his professorship, and compared the Academy’s rules to the institution of serfdom:

“I belong not to Berlin’s Academy of Arts, but to humanity, which has the right to demand the greatest possible cultivation of my abilities; and it has never occurred to me, nor did I ever promise—in exchange for the sum of money that has been given me for several years to develop my talent—to make myself the Academy’s lifelong serf. I can only develop myself [as an artist] here, among the greatest artworks in the world…”.

Carstens’ declaration of freedom would pave the way for a new understanding of the artist as an autonomous individual, rather than the servant of society’s institutions. Thorvaldsen admired the revolutionary Carstens, who was also his friend; it is beyond doubt that he was familiar with Carstens’ declaration, and quite likely that it inspired him to make his own declaration seven years later to the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, defying its demand that he return to Denmark. With regard to Thorvaldsen’s political sympathies, evidence can be gleaned from an article by Georg Brandes, who cites a number of critical remarks about them by the German painter Wilhelm von Schadow: “In those days one could hear, every evening, a pretty atheistic lecture à la Ruge or Feuerbach in Café Greco by one or another young North German … Thorvaldsen, with his simply all too receptive sensibility and understanding, fell all too easily into line with such thinking … In politics he was as radical as one could be.”

Another artist in Thorvaldsen’s circle who fought for artistic freedom was the painter Joseph Anton Koch. Deeply dissatisfied with the educational offerings at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, Koch formed an anti-academic cooperative in 1809, The Brotherhood of St. Luke, together with such sympathizers as Johann Friedrich Overbeck and Franz Pforr (1788-1812). Members of this Brotherhood also called themselves “Nazarenes,” because they idealized a Jesus-like look with long hair alla nazarena. This gentleness, however, was accompanied by wildness too. Noack describes one of Koch’s happening-style performances at Caffè Greco, in which Koch hopped onto a table and crowed like a rooster, as an example of the unrestrained episodes that helped give the café its atmosphere: “Life at Caffè Greco was characterized by a rare blend of seriousness and pride, profundity and levity, idealistic striving and a childlike zest for life.”

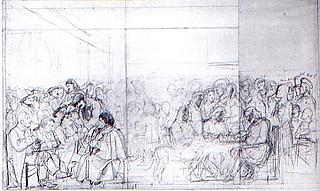

Karl Philipp Fohr: Die Künstler im Antico Caffè Greco [The artists at Antico Caffè Greco] (1818). Pencil on paper, dimensions currently unknown, Städel Museum, Frankfurt.

Second sketch of a never-completed painting. On the left, a group of landscape painters with Joseph Anton Koch in the middle; on the right, a group of Nazarenes surrounding Johann Friedrich Overbeck.

The coffeehouses lose ground to the artists’ organizations

Coffee houses were not the only sanctuaries open to artists and freethinkers, but they acquired great importance not least because of their free availability. Other places where a person like Thorvaldsen could probably have expressed himself as freely (and as critically toward the established order) as at the cafés were in the more exclusive societies and salons, which were open to members or by invitation. In Copenhagen, Thorvaldsen joined the radical left-wing Borup’s Society (founded in 1780). In Rome, he attached himself to the dissident Russian author and singer Princess Zinaïda Volkonskaia, who led an important salon in Rome during part of the 1820s and once again starting in 1829, when she moved permanently from Moscow to Rome as a result of her adversarial relationship to Czar Nikolaj 1. Volkonskaia’s salon was also frequented by the Russian author Aleksander Pushkin (1799-1837), among others.

As for the coffeehouses: despite their status as cosmopolitan commons and political sanctuaries, they did not long remain unconditionally vital meeting-places for the foreign artists and intellectuals in Rome. The times changed dramatically; Europe’s nation-states came into focus—and shortly before the middle of the nineteenth century, artists’ associations established on the basis of national (or, at times, regional) commonalities began to appear. Coffeehouses lost ground to these associations, and lost their air of unavoidability too—even though Caffè Greco in particular continued to be eagerly sought out during the second half of the nineteenth century by the first generation of modernists, such as the French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867).

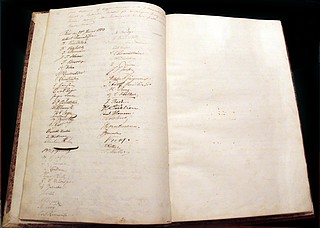

The first hints of a Nordic artists’ association emerged with Den Danske Bogsamling i Rom [The Danish Book Collection in Rome] in 1833, a library founded already in 1832 by Edvard Collin—cf. his letter to Thorvaldsen dated 21.4.1832—and with help from the likes of Thorvaldsen and Andersen. In 1860, a Scandinavian association for artists and cultivators of science, or Circolo Scandinavo [Scandinavian Circle], was founded on the basis of the existing Danish and Swedish libraries, and with financial support from the Scandinavian governments. This took place in parallel to the founding of the Bibliothek der Deutschen [Germans’ Library] in 1826, followed in 1845 by the Deutscher Künstlerverein [German Artists’ Association]; other countries obtained their own national meeting-places similarly. The emergence of these artists’ associations must be regarded as a boon for the artists themselves, and as positive recognition by their home countries of their presence in Rome. At the same time, the new national self-segregation that these associations encouraged can hardly be called a promising development for the local art scene.

Signatures from the founding of Den Danske Bogsamling i Rom [The Danish Book Collection in Rome] on January 28, 1833. Thorvaldsen’s signature appears at the top of the first column. Property of the Scandinavian Circle, Rome.

The shift from cosmopolitan coffee-rooms to national artists’ associations took place in parallel to the buildup of nation-states that was then taking place in much of the rest of Europe. With regard to relations between the Danes and Germans—two prominent groups at Caffè Greco—it does seem that the two Schleswig Wars, in 1848 and 1864, did greatly affect the forms of their interactions in Rome. Hauch, for example, writes with sad longing of the days before the wars, when “the Danish and German artists … interacted with each other quite intimately … When one thinks back … it is as though one’s gaze has been fixed onto … a time so different from ours that one ought to believe that they were separated by centuries. In such dreams of the past, Rome was no longer “the home of peace,” as it had once been. The conflict betwen Danes and Germans on battlefields far from Italy also drove a wedge between artist-colleagues in Rome.

This example illustrates how the open environment that, during the years just before and just after 1800, had brought foreign artists in Rome together across nationalities, was partly dismantled by mid-century. A second reason for the dwindling number of foreign artists participating in the societies surrounding Rome’s coffeehouses in the late nineteenth century is that such artists now tended to fall more for Paris, which was then replacing Rome as the new artistic mecca. Despite this, Caffè Greco remained standing—and can still be visited today.

Caffè Greco today: a visit to the past

Caffè Greco is now Rome’s oldest existing café. It is preserved in grand nineteenth-century style, with wine-red tapestries, medallion portraits, stucco, glass doors, mirrors, and red upholstered furniture. Even today, many artworks and curios from Thorvaldsen’s day remain on display on the walls and shelves. However, the café is no longer the living center for artists and intellectuals that it was during the period from the late 1700s to the mid-1800s. This is already evident from the café’s impeccably intact interior. While the world around Caffè Greco has changed, the café itself has remained standing like a well-preserved frame or stage—though without being marked or frequented by the city’s artists and intellectuals to any comparable degree. On the other hand, one can certainly pursue the traces of the past there.

Renato Guttuso: Caffè Greco (1976). Acrylic on paper,

186×243 cm, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

In Guttuso’s sketches of Caffè Greco, past and present are melted together; the café guests of the present (1976) are portrayed together with the artistic leaders (mainly Italian) of a relatively recent past.

In his many sketches and paintings of Caffè Greco, the Italian artist Renato Guttuso (1911-1987) portrayed the café as a place where different epochs meet—where the flirting couples and tourists of his own day mingled with leading Italian artists and intellectuals of a relatively recent past, such as the painter Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978) and the author Gabriele d’Annunzio (1863-1938). In this manner, Guttuso portrayed the café’s various rooms as spaces still inhabited by the ghosts of the past—who are, however, seated benignly at the same tables as the customers of the present day. Guttuso’s paintings have been a source of inspiration for the darkly smoldering Café Deutschland paintings produced in the 1980s by the German artist Jörg Immendorff (1945-2007). The latter paintings include clear echoes of Guttuso’s works, but express them in a different setting, namely, the (nightmare) world of postwar Germany.

As Guttuso’s paintings suggest, today’s customers at Caffè Greco are predominantly tourists, who come for the experience of inhabiting the spaces where the leading lights of prior generations once held forth. Literary and artistic arrangements are also held frequently in the café’s rooms; but the days are long gone when Caffè Greco could be an unavoidable meeting-place for artists in Rome, many of whom stopped by practically every day. Today, the café’s prices are set with tourists in mind; they no longer permit a diverse fixed clientele. Nevertheless, the well-preserved rooms of Rome’s oldest café continue to provide a window to the past. Visiting Caffè Greco today, one can still intimate what the café once was and meant, long ago.

References

- Louis Bobé: ‘By- og Kulturbillede af Rom i anden Halvdel af det 18. Aarhundrede’, in: Rom og Danmark, vol. 1, Copenhagen 1935, p. 318.

- Georg Brandes: ‘Thorvaldsen og nogle Kvinder’, Tilskueren, Copenhagen 1920.

- Carl Ludwig Fernow: Leben des Künstlers Asmus Jakob Carstens, ein Beitrag zur Kunstgeschichte des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts, Leipzig 1806.

- Jürgen Habermas: Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit, Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft, Neuwied 1962.

- Carsten Hauch: ‘Caffè Greco’ in: Danmark Italia, Hellerup 1996, p. 74-77.

- Arne Hall Jensen: ‘Thorvaldsen og hans samtidige paa Café’, in: Gads Danske Magasin, vol. 44 (March 1950), p. 138-150.

- Friedrich Noack: Deutsches Leben in Rom 1700-1900, Stuttgart & Berlin 1907, p. 95.

- Friedrich Noack: Das deutsche Rom, Rome 1912.

- Ludwig Richter: Lebenserinnerungen eines deutschen Malers, Frankfurt am Main 1980, p. 175.

- Ursula Peters: ‘Das Ideal der Gemeinschaft’ in: Künstlerleben in Rom, Nuremberg 1991, p. 157-187.

- Rudolf Zeitler: ‘Der neue Klassizismus des späten 18. Jahrhunderts – Kunst des Aufbruchs’, in: Asmus Jakob Carstens, Schleswig 1992.

Last updated 14.11.2022